Andrew McGregor

A speech delivered to the Egmont Royal Institute for Foreign Relations, Brussels, June 18, 2013

Egmont Introduction: This paper addresses the question of terrorism in Africa and the role of international and regional organizations in dealing with this phenomenon in Africa specifically and the larger world in general.

This is an important topic at a time when every Western nation is looking to reduce its military and security budget, making it essential to develop less reactive and more pre-emptive means of coping with emerging terrorist groups.

In the African context, it is often difficult to distinguish between terrorism and insurgencies. Many groups use both sets of tactics. We should also recognize that Jihadism and terrorist tactics are not new in Africa, nor are the latter the preserve of African societies as any student of colonial history could tell you. Even the global element of Jihadism is not new; see 19th century Sudanese Mahdism, which intended to convert the world. What is new is the shift from Sufi-Jihadism to Salafist-Jihadism, a gradual development in Africa but something that has happened fairly quickly elsewhere, such as Chechnya, where the transition occurred largely between the Chechen-Russian war of 1994-96 and the beginning of the second Chechen-Russian war in 1999. Older forms of jihadism were often inspired by religious study in the Hijaz or Yemen. In this sense Somalia’s Muhammad Abdullah Hassan, the Sudanese Mahdi, the Libyan Grand Sanusi and other Sufist jihad leaders of the past are all much like Iyad ag Ghali, the Tuareg Ansar al-Din leader who was first brought to conservative Islam by Tablighi missionaries in Mali and then made contacts with Salafi extremists while working as a diplomat in Jeddah.

Disenfranchised or impoverished populations are rarely “the root cause” of terrorism, but such populations are easily recruited to form the mass needed to occupy territory as in northern Mali. International attention tends to focus on economic threats to foreign interests while regarding society-destroying tactics such as mass-rape as local problems of secondary interest. This approach is ultimately an illusion – shattered societies are breeding grounds for religiously-inspired terrorist groups.

Key Role for Regional Organizations

Financial surveillance as a means of tackling terrorism is as important as aerial surveillance, but here the view is obscured by corruption in the banking and regulatory systems of less-developed countries (again, not a purely African phenomenon). Nonetheless, such surveillance is essential as self-financing terrorist networks such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb evolve. A great deal of detailed, expensive and economy-slowing work has been done to regulate international money transfers to cut off sources of terrorist financing, but all this work is quickly undone when nations pay enormous cash ransoms for their kidnapped nationals. Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s financing doesn’t come from the Gulf, it comes from Europe and Canada.

Development remains the best way to engage diverse populations in economic pursuits rather than political violence, but development needs to be handled in a cooperative international fashion. This is where regional economic groupings like IGAD and ECOWAS can play important roles. One such example is the unilateral decision of Ethiopia to build a series of enormous dams on the Blue Nile. What might have benefited the entire region is instead seen as a provocative and hostile action that could lead to a general war or a proxy war using terrorist organizations or insurgent groups.

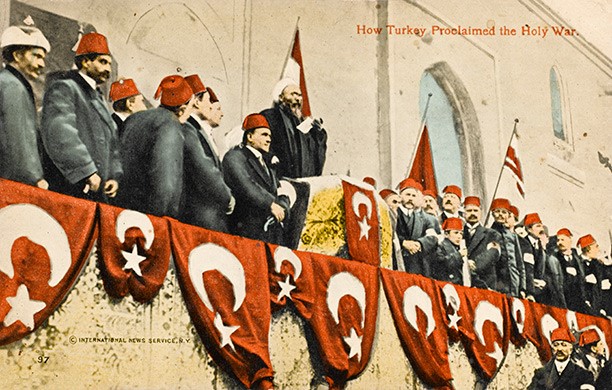

In August 1914 the Ottomans issued a call for jihad against the Allied Powers that would have serious implications for Africa

In August 1914 the Ottomans issued a call for jihad against the Allied Powers that would have serious implications for Africa

In tackling terrorism, there needs to be a greater emphasis on regional blocs rather than UN activity. Neighbors will tend to understand each other and have greater commitment to eliminating sources of instability that might threaten them eventually. UN missions have too many chiefs and extended chains of command in which military decisions require approval from civilian authorities in New York. UN intervention or peacekeeping operations often consist of polyglot forces from nations of “professional peacekeepers” like Fiji, Colombia or Bangladesh that have little to offer in terms of military skills but join any mission going in order to take advantage of the financial compensation and military materiel available. Regional partners tend to perform better as they have a national interest in the success of the mission.

Rapid reaction forces formed by each regional grouping might be “adopted” by a Western power, perhaps monitored by an international committee and/or a regional political grouping to prevent the growth of a “sphere of influence.”

All too often, the more inclined we are to make intervention efforts international, the less likely they are to work. Successful interventions tend to revolve around one capable military force that dictates the rate of progress and dominates the upper levels of the command chain. See, for example, France in northern Mali, or Uganda in Somalia. As in the latter case, these forces do not necessarily have to be Western, but would still benefit from Western financial, logistical and intelligence support.

Nonetheless, impartial assessments of national military capabilities are necessary before deployment on joint missions. See for example Nigerians showing up in Mali without food or ammunition when they were supposed to be the core of the force. Aside from Chad and Niger, who operated in close cooperation with the French independently of the rest of the African contingents, the ECOWAS force has contributed little and may even have drawn off resources that could have been better applied in the intervention. In other words, rhetoric that calls for “African solutions to African problems” can itself be a problem. Creating “feel-good” alliances is not the same as creating effective military alliances. Sober assessments free of political considerations must be conducted to determine where limited security resources can be most advantageously applied.

Rethinking International Interventions

In struggling societies that are enduring economic collapse, environmental degradation and government corruption, people typically develop alternative methods of survival, and there is often little difference between terrorism, jihadism, narco-trafficking and smuggling. All these activities are mutually supportive and all require international cooperation to combat. The existence of trans-national criminal networks can be easily adapted to the needs of terrorists. As the jihadists fight a borderless war, one of the greatest advantages they have in Africa is the existence of national borders. In Africa, the jihadis are able to exploit the failure of nation-states to cooperate fully on security issues by sharing intelligence or mounting joint efforts at border control.

There is a need to reassess international military programs such as the U.S.-sponsored Operation Flintlock, which created an elite cadre in the Malian Army that used its training to overthrow a democratically elected government (flawed though it may have been) rather than combat terrorism. Training is all very well, but there needs to be even closer engagement. How can Malian troops defend national sovereignty when they are sent to the front without sufficient ammunition because funds have been diverted? What’s cheaper – a full scale, year-long military intervention or a shipment of ammunition? Escalation of conflicts can often be avoided by small measures such as making sure security forces are actually paid on time. Many members of terrorist organizations are not ideologically committed – see Somalia, where there has been steady movement of fighters between al-Shabaab and government armed forces according to which group was actually meeting their payroll. Peacekeeping troops or security forces that go unpaid quickly turn to selling the most valuable assets they have on hand – their weapons.

Reintegration as a component of conflict resolution also needs to be rethought. Too often, it is a means for defeated rebels to train, re-equip and re-arm before launching a new rebellion – see for example the M23 mutineers of the DRC and the Tuareg rebels of Niger and Mali, some of whom have gone through the desertion/rebellion/reintegration process several times. Reintegration is a survival tactic that preserves not only lives and military formations, but also unwittingly provides an available pool of trained fighters to supply tomorrow’s insurgencies with manpower.

Combating arms proliferation would seem to be an area that could benefit immensely from international cooperation, but it is the same nations that profit most from the arms trade that ironically would be the most capable of controlling it. Such conflicts of interest prevent effective measures from being taken. There are no guarantees in the arms trade – today’s secure arsenal easily becomes tomorrow’s arms bazaar (see Libya), or arms provided for counter-insurgency or counter-terrorism work today may be turned on civilian populations tomorrow in a type of “state terrorism.”

Eliminating Terrorism: A Conflict of Interest?

Eliminating Terrorism: A Conflict of Interest?

And finally, there must be some recognition that we’re not all on the same page in the international community regarding the means or even desirability of eliminating terrorism. A great deal of what we describe as terrorism is in fact proxy warfare. There are very few terrorist groups that survive their first year of operations without clandestine external support or internal support from “deep state” elements or even rogue elements of the security services. One might look here to the long and continuing run of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Central Africa, which, despite a near total absence of ideology or authentic local support, has still managed to terrorize the region for decades as a proxy of the Sudan in its political struggle with Uganda.

In addition, many states find a certain level of instability in their neighbors (a level they would probably describe as “containable” if pressed) to be a useful means of exerting influence or preventing the emergence of a national unity or purpose that might prove threatening to their interests. In this case one might examine Ethiopia’s intervention against al-Shabaab in Somalia – while Ethiopia by no means aids or abets this terrorist group, it also has little interest in allowing Somalia to become a unified and cohesive state that could resume its pursuit of irredentist activities at Ethiopia’s expense, as it did in the 1970s. Other states may find a controlled level of internal instability to be useful as a tool of state preservation as they say, “Without us, look at who would take over the state” or to borrow Louis XV’s apocryphal warning; “Après nous, le deluge.”

When we examine all these tendencies simultaneously, it becomes apparent that international groupings will ultimately choose the path of action that is the least offensive to their membership rather than choosing the most effective solution every time.

Now while we are on relatively firm ground in dealing with the economic, social and political aspects of terrorism, all of which are areas that can be measured, analyzed and understood in some rational fashion, there is also the religious dimension, especially in the African context, which is instead a matter of faith. Much of the terrorist activity we are witnessing in Africa at the moment is the result of the growth and spread of Salafist Islam in Africa. Salafism is in itself not a terrorist movement, and is not illegal in most nations – indeed, it would be folly to make it so. However, I think it is fair to say that Salafism often acts as a gateway to Takfirism, the phenomenon of believing that only you and your associates possess the correct interpretation of Islam based on the works of a very selective group of scholars, such as Ibn Taymiya and his followers. Being possessed of this righteous interpretation of scripture and scholarly analysis, the Takfiri must then counsel others to follow that interpretation or condemn them as apostates with all the requisite punishments that accompany that declaration. In this way, the inflexibility of Salafism fuels religious and political extremism. Religious movements, like shifts in social attitudes, are much harder to contain than armed groups. Insurgent groups based on purely political motivations, such as extremists of the right or left, can usually be extinguished with some permanency – not so, however, with religiously motivated extremists, who may rally to form an immediate replacement for groups that have been successfully eradicated, often using that eradication as their inspiration. It is difficult to define a role for international organizations in stemming the growth of Takfirism, which, being an ideology, cannot be controlled in the way arms flows or financial transactions can be interdicted and controlled.

It is necessary to conduct an honest examination of our own national and economic motivations and desires if we are at all sincere in addressing the phenomenon of international terrorism. In this quick look at a few aspects of the international community’s approach to terrorism in Africa, I’m reminded of the famous phrase uttered by a character in the satirical American comic strip Pogo, whose eponymous leading character was fond of saying “We have seen the enemy, and he is us!”

This speech was delivered at the Egmont Royal Institute for Foreign Relations symposium Time for a New Approach on Terror in Africa? held in Brussels on June 18, 2013. A transcript appeared in Jean-Christophe Hoste and Julie Godin (ed.s), Time for a New Approach on Terror in Africa?, Academia Press, 2014, pp. 65-69.