Andrew McGregor

June 27, 2013

Only three months after a long and bitter dispute over South Sudanese oil flows through Sudan was resolved, the pipeline from the South is in danger of being cut off once again, to the mutual disadvantage of both states. The earlier dispute, which saw oil flows from South Sudan suspended for 16 months, was based on a dispute over pipeline fees. Now political considerations have come to the fore, with Khartoum demanding that South Sudan stop its alleged support of forces belonging to the rebel Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) in the Darfur, Kordofan and Blue Nile regions. Khartoum’s decision comes at a time when it has been unsettled by rebel advances in North Kordofan province that could eventually open the road to a strike on the capital itself.

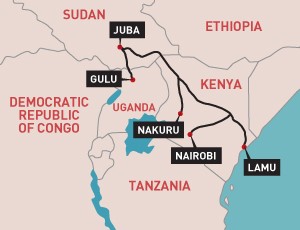

Route of Proposed New Pipeline (ENR)

Route of Proposed New Pipeline (ENR)

In a June 8 rally in Khartoum, Bashir announced he had told his oil minister to “direct oil pipelines to close the pipeline and after that, let [South Sudan] take [the oil] via Kenya or Djibouti or wherever they want to take it… The oil of South Sudan will not pass through Sudan ever again” (Sudan Tribune, June 17). The Sudanese government has said the pipeline must be shut down in a gradual 60-day process and that all oil within the pipeline are already in Port Sudan will be shipped out as usual (Sudan Tribune, June 15). The affected oil shipments belong to the China National Petroleum Corporation, India’s ONCG Videsh and Malaysia’s Petronas.

Even if the current dispute was resolved quickly (which looks unlikely), it will still have the result of encouraging plans to develop a new pipeline to carry South Sudan’s oil to Djibouti or Kenya’s Lamu Port instead of Port Sudan. The planned pipeline to Lamu Port would be joined by another new line from Uganda, which has been determined to have a commercially viable three billion drums of oil (Daily Nation [Nairobi], June 18).

However, for the pipeline to Lamu Port to become a reality, new oil discoveries are needed in South Sudan. Most of these hopes are centered on potential discoveries in the massive but promising Jonglei B Bloc that was formerly a concession of French oil firm Total. The B Bloc has now been divided into three parts, with Total joining in a partnership with U.S. Exxon Mobil and Kuwait’s Kufpec in at least two of these blocs (Reuters, June 4). Unfortunately, eastern Jonglei is the home of the Yau Yau rebellion, an obstinate challenge to South Sudan’s success that Juba believes is supplied and organized by Khartoum (for rebellion leader David Yau Yau, see https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=278 ). South Sudan president Salva Kiir Mayardit is reported to have discussed construction of the new pipeline with the Toyota Corporation of Japan during a visit to that country (al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 20).

Sudanese Presidential Advisor Nafi Ali Nafi (Sudan Tribune)

Sudanese Presidential Advisor Nafi Ali Nafi (Sudan Tribune)

The previous dispute over oil transfers was solved by a Cooperation Agreement signed in September, 2012 and implemented in March that covered oil and other issues, such as border security, citizenship, trade, banking and even the creation of a buffer zone between the two nations. Following Khartoum’s decision to suspend the Cooperation Agreement with South Sudan, Washington postponed an already controversial visit to the U.S. capital from Sudanese presidential adviser Nafi Ali Nafi, one of the most powerful men in the regime and a possible future presidential candidate, but also a figure many believe should be charged by the International Criminal Court for his role in various human rights abuses (al-Sanafah [Khartoum], June 19).

Efforts to reconcile the two Sudans have been led by former South African president Thabo Mbeki, currently chairman of the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel. China, which stands to lose a major source of oil over the tensions between Khartoum and Juba, has joined the AU in seeking a resolution to the dispute. Khartoum has indicated its acceptance of an African Union proposal that would see the re-implementation of the cooperation agreement once the South Sudanese army was removed from the demilitarized zone between the two nations, but with both Khartoum and Juba still accusing the other of maintaining proxy forces within their respective territories, there are still important issues to be resolved if South Sudanese oil is to continue being pumped to Port Sudan after the two-month warning period ends in early August. South Sudan vice-president Riek Machar has been assigned to visit Khartoum to discuss means of resolving this latest crisis, but a date for the visit has yet to be set (al-Sahafah [Khartoum], June 16; al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 20).

South Sudan’s Foreign Minister, Nhial Deng Nhial, insists that his government is ready to fully implement all the conditions of the Cooperation Agreement: “The Republic of South Sudan does not support rebels fighting Khartoum. It is in our interest not to destabilize the government of Sudan” (Sudan Tribune, June 23). Deng Alor, minister of cabinet affairs of South Sudan, remarked: “We do not want to enter into a military confrontation with Khartoum; not owing to weakness, but in order to maintain peace and its achievements… However, this does not prevent us from exercising our right to self-defense” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 20).

On June 20, the Khartoum government announced sweeping changes to the military leadership, including the top positions in the army, air force, navy and intelligence service. The new chief-of-staff is Lieutenant General Mustafa Osman Obeid Salim, who succeeds Colonel General Ismat Abd al-Rahman. While government sources described the replacement of 15 senior officers as routine, it is widely believed the broad changes in the command structure reflected a lack of confidence in the existing commanders, who were unable to prevent the Sudanese Revolutionary Front from taking the town of Abu Kershola in South Kordofan and attacking the North Kordofan town of Um Rawaba in a lightly-resisted spring offensive that embarrassed government leaders. The SRF even fired four shells on a military airbase outside the North Kordofan capital of Kadugli on June 14, though the shells actually fell on part of the facility used by the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), killing one Ethiopian peacekeeper and wounding two others (Sudan Tribune, June 14; Akhir Lahzah [Khartoum], June 18).

Military developments in North Kordofan have clearly alarmed the regime in Khartoum, which has set up 27 checkpoints at entrance points to the capital to prevent the infiltration of SRF fighters (al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 20). Nafi Ali Nafi made an unusual public criticism of the army afterwards, saying its low combat capability meant it was struggling to deal with the rebels and was in need of new recruits. His remarks were taken poorly by the Army, whose spokesman Colonel al-Sawarmi Khalid Sa’ad proclaimed that “if it wasn’t for the Sudanese Army… these [rebel] movements would have now seized the city of Khartoum and the regime would have totally collapsed” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, June 20; Sudan Tribune, June 20). Nonetheless, the president’s adviser appears to have come out on top in this struggle – most of the officers newly appointed to command positions are believed to be Nafi loyalists. The widespread changes to Sudan’s military leadership also appear to have weeded out some senior officers whose loyalty was suspect after being charged and then pardoned by the president in connection with an alleged coup attempt last November. [1] Only a few of those detained remain behind bars, including Major General Salah Ahmed Abdalla and Lieutenant General Salah Abdallah Abu Digin (a.k.a. Salah Gosh),a former head of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) known for his political rivalry with Nafi Ali Nafi and his close cooperation with the CIA in counterterrorism matters.

Note

- For the coup, see Andrew McGregor, “Sudanese Regime Begins to Unravel after Coup Reports and Rumors of Military Ties to Iran,” Aberfoyle International Security Special Report, January 7, 2012, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=141.

This article first appeared in the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor on June 27, 2013.