Dr. Andrew McGregor, Aberfoyle International Security

Shout Monthly, Toronto

October 2002

As the Bush administration promotes regime change in Iraq, it finds elements of its armies in action against Muslim foes in Afghanistan, the Philippines and Georgia. Preparations are ongoing for assaults on Yemen and, ultimately, Iraq. In the midst of all this military activity the US administration must convince the rest of the Islamic world that ‘regime change’ in Muslim countries is not an attack on Islam itself. George W Bush might look at the experience of an earlier ‘Republican’, Napoleon Bonaparte, who two hundred years ago also found himself trying to overthrow local Islamic rulers while trying to assure Muslims of his respect for Islam.

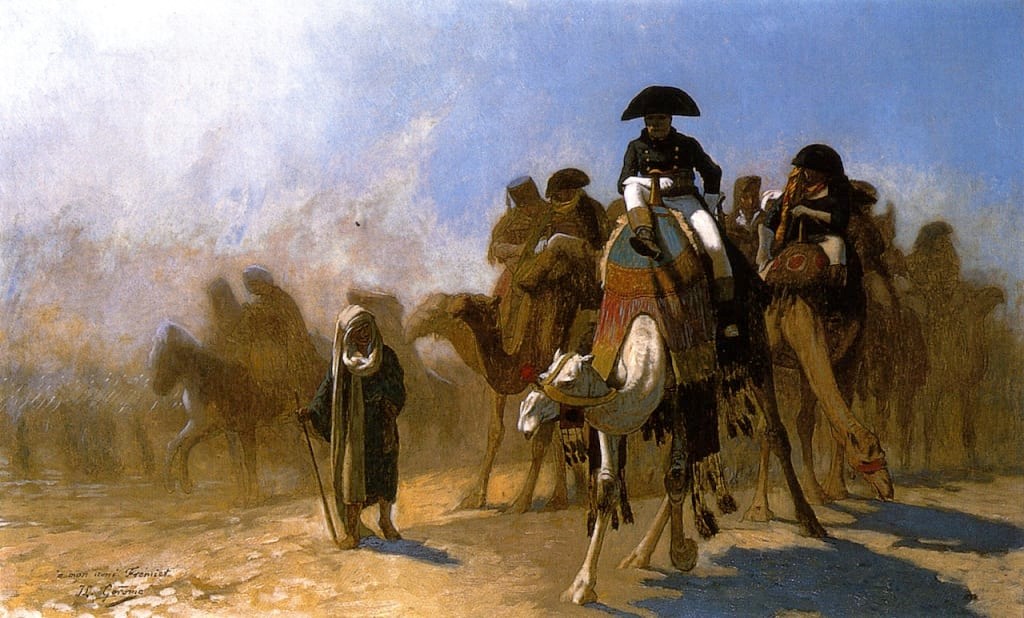

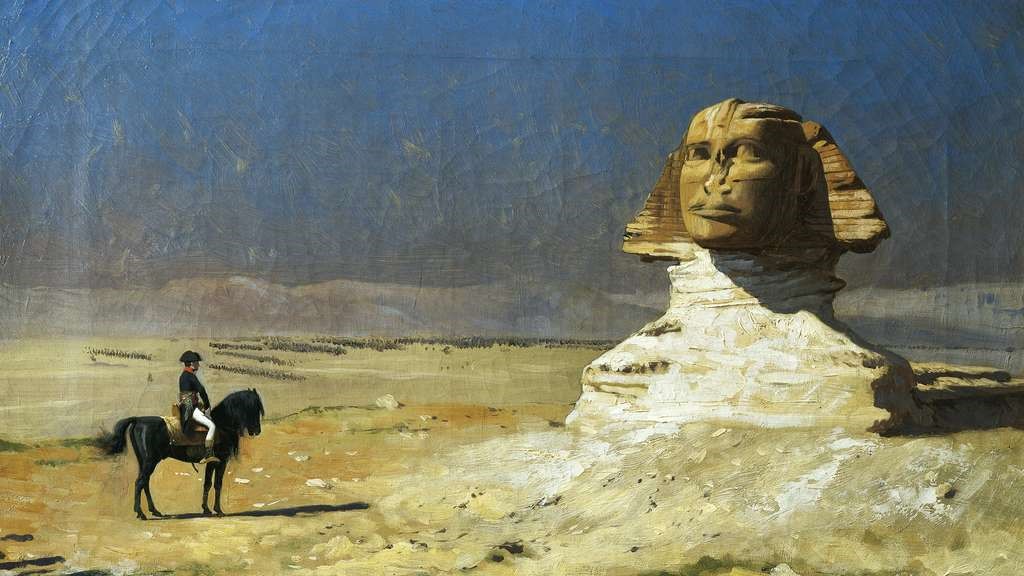

In 1798, while still a general in the army of Revolutionary France, Bonaparte was entrusted with a bold mission designed to seize Egypt and reopen the ancient trade route to the East through the Suez. Egypt was still a land of mystery to the Europeans, ruled nominally by the Ottoman Turks, but in practice by a military caste known as the Mamluks. The latter were brought as slaves to Egypt from the Caucasus and Central Asia and trained in the military arts. The Mamluks amused themselves with constant and bloody struggles for supremacy as well as looting the merchants and citizenry at will. In arrogance they were unsurpassed, and few of them ever bothered to learn the language of their subjects, Arabic. The Mamluks, however, never forgot to present themselves as benefactors and patrons of Islam, often giving rich endowments to Koranic schools and Islamic foundations.

After Bonaparte had driven the Mamluks from northern Egypt he sought to impress the Islamic establishment by attending their prayers and Koranic discussions. One time, Bonaparte’s aides discovered the general awaiting the Islamic council in Turkish garb. Horrified, (“He cut such a poor figure in his turban and caftan”) they persuaded Napoleon to change before the arrival of the dignitaries. Eventually Bonaparte became known as a talib, or student of Islam. (The Afghan “Taliban” were so-named for the participation of students from Pakistan’s madrassa-s, or Islamic schools, as fighters in the early stage of the Taliban conquest of Afghanistan).

After Bonaparte had driven the Mamluks from northern Egypt he sought to impress the Islamic establishment by attending their prayers and Koranic discussions. One time, Bonaparte’s aides discovered the general awaiting the Islamic council in Turkish garb. Horrified, (“He cut such a poor figure in his turban and caftan”) they persuaded Napoleon to change before the arrival of the dignitaries. Eventually Bonaparte became known as a talib, or student of Islam. (The Afghan “Taliban” were so-named for the participation of students from Pakistan’s madrassa-s, or Islamic schools, as fighters in the early stage of the Taliban conquest of Afghanistan).

Just as President Bush quickly retracted his early use of the word “crusade” to describe his anti-terrorist action, Napoleon also strove to separate himself from the traditional model of Christian/Islamic enmity; “We have nothing to do with those infidels of barbarian times who came to fight against your faith; we recognize its sublimity, we adhere to it, and the moment has come when all regenerate French will also become true believers.” Bonaparte proclaimed the Republic’s imprisonment of the Pope and his own destruction of the Knights of Malta to the skeptical Islamic leaders as proof of his army’s detachment from Christianity. Napoleon further claimed that his successes were the result of the will of Allah and the protection of the Prophet Muhammad. The general admitted privately, however, that his Islamic policy was designed to “lull fanaticism to sleep before we uproot it.”

At one point, Bonaparte met with a panel of Cairo’s learned shaykh-s and agreed that he and his army would convert to Islam in exchange for a fatwa (religious ruling) ordering the submission of Egyptian Muslims to French rule. The astonished shaykh-s reminded Napoleon of the usual provisions regarding circumcision (not practiced in France at the time) and the prohibition of wine. Unwilling to approach his troops with these conditions, Napoleon attempted to negotiate with the scholars. While the shaykh-s proved flexible on the question of circumcision, they were adamant on the prohibition of wine, the life’s-blood of the French army. In time it was agreed that wine drinking could be overlooked if the soldiers donated one-fifth of their wages to charity. Napoleon eventually lost his enthusiasm for this idea, but many of his men (including a leading general) converted privately to Islam in order to take Egyptian wives.

At one point, Bonaparte met with a panel of Cairo’s learned shaykh-s and agreed that he and his army would convert to Islam in exchange for a fatwa (religious ruling) ordering the submission of Egyptian Muslims to French rule. The astonished shaykh-s reminded Napoleon of the usual provisions regarding circumcision (not practiced in France at the time) and the prohibition of wine. Unwilling to approach his troops with these conditions, Napoleon attempted to negotiate with the scholars. While the shaykh-s proved flexible on the question of circumcision, they were adamant on the prohibition of wine, the life’s-blood of the French army. In time it was agreed that wine drinking could be overlooked if the soldiers donated one-fifth of their wages to charity. Napoleon eventually lost his enthusiasm for this idea, but many of his men (including a leading general) converted privately to Islam in order to take Egyptian wives.

The Bush administration has conceded that anti-terrorist action in the Middle East and Central Asia will not succeed without the cooperation of Muslim states, and has worked hard to create an inclusive ‘alliance’. Bonaparte also realized that the French occupation of Egypt could not survive without the acquiescence of Egypt’s Muslim neighbours. A diplomatic correspondence started, with Napoleon proposing alliances with sultans from India to Morocco. Napoleon even suggested that the mysterious Sultan of Darfur in the African interior provide him with thousands of black slaves to replace his ever-shrinking number of French soldiers.

In his correspondence, Napoleon stressed that within his territory the mosques were open, religious traditions were respected, pilgrimage was protected, and Islamic festivals celebrated with more grandeur than ever. In practice mosques were destroyed to create fields of fire for French artillery near the Citadel, taverns were opened everywhere in Cairo, and the pious citizens forced to watch their unveiled daughters consorting with French soldiers. The scandalized Egyptian chronicler, ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Djabarti, recorded that “the French prided themselves on their slavery to women.”

Nevertheless, it was a real-estate tax that sparked a vicious urban revolt in Cairo. The rebellion was brutally repressed through many days of horror in Cairo’s narrow streets and courtyards. In victory Bonaparte appeared magnanimous, but from that point on the volleys of firing squads could be heard behind the Citadel walls each night, their victims dumped quietly into the Nile before daybreak. So many were killed that eventually the French found it necessary to change the method of execution to decapitation in order to make less noise and save precious ammunition.

Napoleon’s occupation army was intended to be supported by the French fleet, but Nelson’s destruction of this force left Bonaparte in need of regional alliances for his isolated regime. Failed overtures to the Ottoman ruler of Syria, the ‘Butcher’, Djezzar Pasha (the Saddam Hussein of his day) led to a disastrous French campaign in Palestine where the army was ravaged by plague and heavy battle losses. The Sharif of Mecca, whose economy was dependent upon coffee exports to Egypt, maintained a pleasant correspondence with Bonaparte while allowing thousands of fierce tribesmen to cross the Red Sea to fall upon the French troops. The eager tribesmen had heard that the French wore armour of gold and silver.

Napoleon abandoned his army to return to France in mid-1799. The army held on until their capitulation to the Turks and English in 1801. In exile at St. Helena, Bonaparte romanticized his Egyptian exploits; “If I had stayed in the Orient, I probably would have founded an empire like Alexander’s by going on pilgrimage to Mecca.”

George Bush is unlikely to contemplate the conversion of himself or his army in order to win over Muslim opinion in the “War on Terrorism.” If the conflict expands beyond Afghanistan to Iraq and Yemen, however, American troops will run into the same problems of distrust and resentment from Muslims that made the French conquest of Egypt impossible. In Afghanistan the limited American presence has not been enough to prevent power returning to the warlords, Afghanistan’s modern “Mamluks.” Afghanistan’s new US-approved president is as powerless as Napoleon’s native appointees in Cairo.

Protestations of friendship and respect will continue to dominate US relations with most of the Muslim world, but there is always the danger of a modern-day Sharif of Mecca turning his eyes when his people begin to join the fray. Bonaparte wrote at the time, wrongly, that “by gaining the support of the great shaykh-s of Cairo, one gains the public opinion of all Egypt.” Throughout the French occupation the Egyptians expressed a preference for misrule by the Muslim Mamluks to the scientific administration of their self-proclaimed benefactors, the infidel French. It was a lesson the French found hard to understand, but one that the Americans must recognize if they are to have success in forming effective governments in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Unilateral imposition of unpopular puppet regimes will not contribute to the security of the Middle East and Central Asia. The real challenge for Washington is the introduction of forms of government that will engage the interest and participation of the citizens of the Muslim world. When under pressure in Egypt, Bonaparte’s republicanism quickly turned to imperialism. Unlike Bonaparte, however, Mr. Bush cannot simply walk away from the Mid-East if the going gets tough. To succeed, “regime-change” must be about governance issues as much as the consolidation of petroleum interests.