The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies

The Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies

Strategic Datalink no. 108

Andrew McGregor

October 2002

In Saudi Arabia there are fears that Iraq may not be the only Gulf state in which the United States is planning “regime change.” US-Saudi relations have reached a crisis point in the wake of repeated charges of al-Qaeda support at the highest levels of the Saudi regime. There is a growing feeling in some quarters of the Bush Administration that the Saudi royal family are no longer reliable allies, and that Saudi oil supplies are at risk from a growing movement of Islamist radicals. For the Saudi regime, however, every expression of political support for the United States comes at a considerable cost to their slowly fading legitimacy. With the royal family, the Americans, and the radical Islamists each striving to consolidate themselves, the once-stable US-Saudi pact is quickly turning into a three-way struggle for the kingdom’s future.

Mounting Pressure in US-Saudi Relations

Mounting Pressure in US-Saudi Relations

News was leaked this August of a recent RAND Corporation briefing on Saudi Arabia to the Defense Policy Board in Washington. The briefing suggested that the US insist the Saudis stop funding Islamist militants, prosecute anyone linked to terrorism and end anti-Israel land anti-US propaganda. Failure to comply should be met by “targeting” Saudi financial assets and oil fields. [1] While the Bush Administration was quick to reassure the kingdom’s effective ruler, Crown Prince ‘Abdullah, the kingdom is now awash in rumours of a coming UN seizure of Saudi oil assets. The leak may well have been designed to place pressure on the Saudi regime to change their opposition to the use of US bases within the kingdom for an attack on Iraq. On September 15, 2002 the Saudi foreign minister stated that the bases may be used in a UN-sanctioned action against Iraq, a major policy change and concession to the Americans.

The once well-entrenched Saudi royal family is now openly opposed by radical Islamist shaykh-s and, to a lesser extent, the government-controlled ulama (religious scholars). The government’s pro-Western stance is not shared by all its citizens. Saudi citizens have been involved in Islamist jihad activities in Bosnia, Chechnya, Daghestan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan, and hundreds have answered al-Qaeda’s call for fighters and terrorists. The continuing presence of permanent US bases in Saudi Arabia since the Gulf War inflames Saudi public opinion. [2] King Fahd only gained the approval of the ulama for their establishment by assurances that they would be closed immediately after the war. Part of the regime’s contract with its citizenry is defence. By ceding this responsibility to the Americans, the regime risks irrelevance. During the Gulf War, Osama bin Laden offered an army of Arab veterans of Afghanistan for the defence of Saudi Arabia. To his everlasting anger, the royal family rejected the offer in favour of an American presence.

The Islamist Opposition

The radical Islamists are not totally at odds with establishment ulama, which often gives subtle approval to radical aims. The ulama, radical or moderate, are all dedicated to distancing Saudi Arabia from the US. Violent responses to the US presence in the kingdom began in 1995 with the bombing of the US mission to the Saudi National Guard. This marked the beginning of the involvement of Saudi veterans of the Afghanistan war in the anti-US struggle. Their actions displayed the influence of Palestinian jihad theorist and practitioner Dr. ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam, who provided leadership and assistance to the Arab volunteers in Afghanistan until his mysterious assassination in 1989. In their confessions the plotters also admitted to being influenced by Saudi opposition leader Muhammad al-Mas’ari and an imprisoned Jordanian Islamist, Abu Muhammad (aka ‘Issam Tahir al-Maqdisi). Before being beheaded, the suspects described the illegitimacy of the Saudi regime and its tame establishment clergy. In their opinion, the royal family and the government-approved ulama had failed to adhere to Islamic Shari’a law, and had further allied themselves to the “Crusader” cause of the Western powers.

Muhammad al-Mas’ari (The Times)

Muhammad al-Mas’ari (The Times)

The Saudi regime has in fact dealt harshly with many Islamic extremists, especially when they are judged to pose a threat to the survival of the royal family. In 1979, Islamists led by Juhayman al-‘Utaybi and Muhammad al-Qahtani seized the Grand Mosque of Mecca in an attempt to overthrow the royal family, terminate the “alliance with the Christians,” and to abolish the establishment ulama. [3] After protracted fighting, all the Islamists who survived were executed. A 1994 crackdown focused on a radical grouping known as the Awakening Shaykhs and the Islamist Opposition Committee for the Defence of Legitimate Rights (CDLR) was disrupted by mass arrests, leading to the self-exile to London of its leader, Muhammad al-Mas’ari. The Movement for Islamic Reform in Arabia (MIRA) has largely replaced the CDLR in the kingdom since 1997. Nevertheless, relations between the Islamists and the Saudi regime are a far cry from the gun battles in Egypt between radicals and government forces. In one sense, the Saudi crackdown actually worsened the situation for the royal family. The dissidents in exile turned to the Internet and of the telecommunications sources, suddenly finding themselves with the means of getting their message into every Saudi home. Expensive efforts by the Saudi government to block the MIRA website have proven futile. [4]

At times, government reaction to criticism from the radical shaykh-s seems hesitant; the reaction of the Minister of Justice to charges of widespread government corruption was to suggest that radical Islamists were promoting fitna (public disorder), “and that is worse than corrupt rule.” [5] British authorities have determined that a November 2000 wave of car bombings directed against Westerners in Riyadh was the work of radical supporters of Bin Laden, but was blamed on Canadian Bill Sampson and other Western Expatriates in an effort to divert attention from the growing Islamist opposition. [6] At the highest levels there is a reluctance to acknowledge Saudi Arabia as a breeding ground for anti-American terrorism; according to Prince Turki al-Faysal, former Saudi intelligence chief, the fact that Bin Laden “chose 15 Saudis for his murderous [9/11] gang… can only be explained as an attempt to disrupt the close relationship between our two countries.” [7]

Beyond Wahhabism

Saudi Arabia is frequently identified as the source of the international Wahhabist movement, an austere Islamic reform movement rooted in Saudi Arabia’s harsh desert interior. Since the 18th century alliance between the Sa’ud family and puritanical Islamist revivalist Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, the Saudi royal family has relied on the support and approval of the Wahhabi clergy for their legitimacy as rulers. Growing opposition to the regime within the establishment Wahhabist ulama has led to attempts to marginalize opposition shaykh-s through the steady restructuring of the government bodies regulating Islam. The radical ulama want to decentralize establishment Islam, ending the process of state control that began with the reforms of King Faysal (1964-75). The new Islamist leaders do not rely on the example of al-Wahhab for legitimacy; the reliance of the royal family upon this figure for their own legitimacy has in some sense devalued this association. [8] Ideologically placed beyond the influence of the government and establishment Wahhabism, the independent Islamist ulama represent a serious threat to the regime.

Islamist Shaykh al-Shuaibi, described by an al-Qaeda spokesman as “one of the great imams [religious leaders] of Saudi Arabia,” has already issued a ruling declaring America to be “an enemy of Islam and Muslims.” Al-Shuaibi also endorsed the radical idea that jihad must be fought against heretical Islamic regimes, implying the Saudi royal family. [9] Osama bin Laden’s appeals to the Saudi armed forces to conduct a guerrilla campaign against American targets inside Saudi Arabia have fallen on deaf ears so far. His own abandonment of a disco lifestyle for the foxholes of Jihad has provided an inspirational model to many Saudis, but his cynicism and assumption of unearned religious authority have dissuaded disaffected Saudis from rallying to his cause. The fact that Bin Laden hails from a Yemeni family rather than a Saudi clan makes indifference to his cause convenient to some Saudis. Even the radical shaykhs are critical of Bin Laden’s strategy, pointing out that he has brought destruction upon Muslim lands. [10] Bin Laden has suggested that the Saudi regime be abolished, with the division of the entire Arabian Peninsula into two new states, “Greater Hijaz” and “Greater Yemen.” [11] Inspirations of this sort are unlikely to garner any support from the lesser emirates of the Persian Gulf. From Kuwait to Qatar, these tiny but wealthy states are largely governed by complacent royal families using a healthy patronage system. They are now discovering that they are not immune to the spread of radical Islamism.

A Kingdom of Arms

Saudi Arabia, despite its immense oil wealth, now runs a deficit, and is having trouble paying for US arms shipments. The re-export of Saudi oil revenues to America in the form of arms orders is a sore point for the Islamists. Many Saudis blame the US for encouraging the regime to waste money on unnecessary weapons. According to a leading Islamist shaykh, Dr. Safar al-Hawali:

Since World War II, America has not been a democratic republic; it has become a military empire after the Roman model. It is even more abhorrent because its administration is ruled by the pressure groups that are the most dangerous to the human race – the companies that create destruction and sell arms. {12]

The Islamists question why $300 billion in arms purchases over the last 25 years have left the kingdom so helpless it requires permanent bases of a foreign power to ensure its security. Defence spending currently consumes 18% of the Saudi budget, compared to 4.5% in the US. The truth is that with its small population and territory the size of Western Europe it has never been possible for Saudi Arabia to defend itself against any of the regional powers. Even the royal family has acknowledged they are entirely reliant upon the US for defence. For the Islamists, Saudi defence spending has the appearance of kickbacks in return for US support of the ruling family.

Crown Prince ‘Abdullah has not hesitated to express his displeasure with America’s unconditional support for Israel, and was thoroughly disappointed with US reaction to his peace initiative in early 2002. When ‘Abdullah gave a speech to Saudi troops departing for action against the Iraqis in 1991 he expressed his sadness that he was not instead witnessing Saudi soldiers and their Arab Iraqi brethren preparing to leave for the liberation of Palestine. Though there is no reason to doubt the Crown Prince’s sincerity in his desire to see a just settlement for the Palestinians, he has been able to use this platform to secure his pan-Islamic credentials in the face of growing pressure from the domestic ulama. In the meantime, the Crown Prince continues to warn Washington that its policies are forcing an irrevocable split between Saudis and Americans.

The Quiet Struggle Between Saudi Arabia and the United States

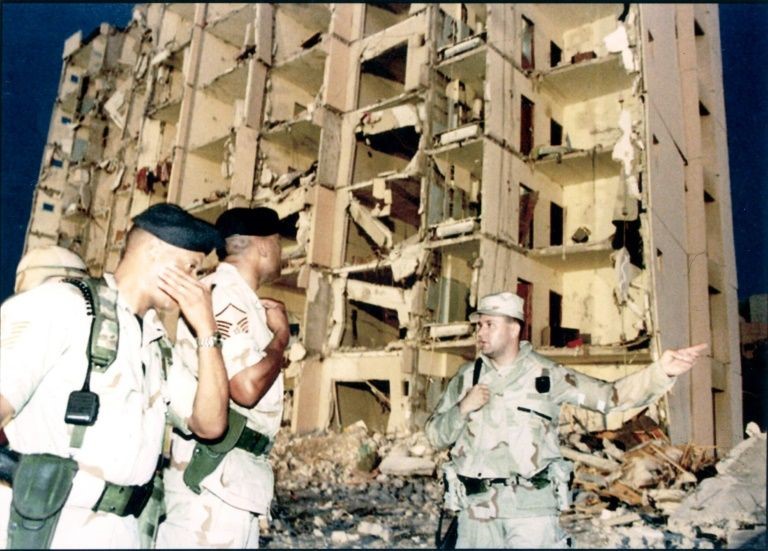

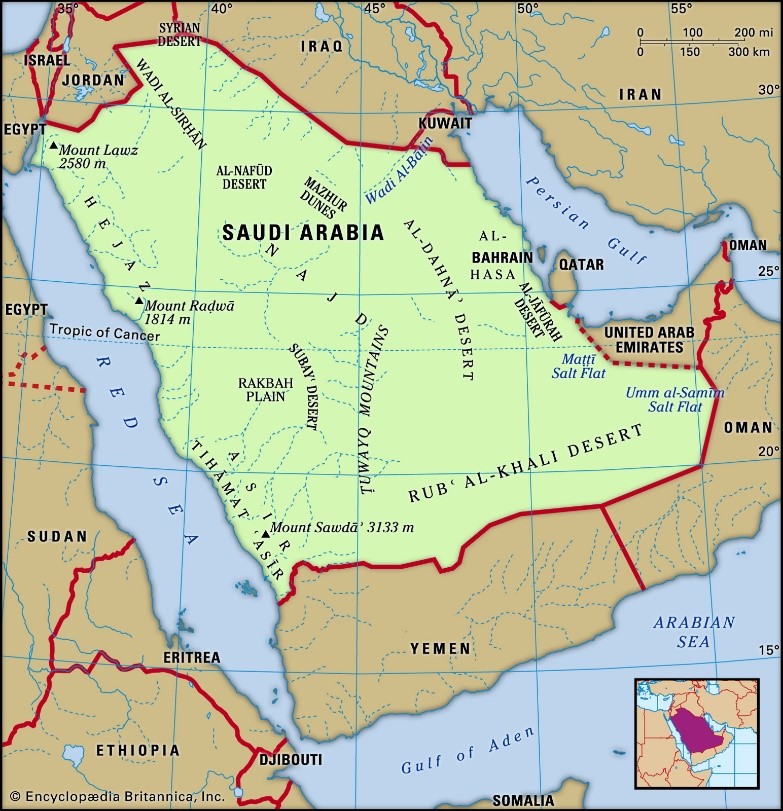

There are a number of open irritations in US-Saudi relations. One is the stagnant investigation into the 1996 bombing of American quarters in the al-Khobar towers in which 19 Americans were killed. Almost certainly the work of Saudi Shi’is working with intelligence agents of the Shi’ite regime in Iran, the later reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran hindered the investigation. Saudi Shi’a compose 25 to 30% of the population of the Eastern Province [13] and are strongly repressed by the Sunni (majority) government of Saudi Arabia. [14] Interior Minister Prince Nayef bin ‘Abdul-‘Aziz denies even the existence of the Shi’ite “Saudi Hizbullah” organization that the US blames for the attack. [15] In the end, the Saudis suggested Iranian participation in the Khobar blast may have been limited to “rogue elements,” in exchange for an Iranian agreement to cease support for radical Saudi Shi’a and the prospect of warmer relations with the new Iranian President, Mohammed Khatami. The failure to bring the case to resolution fuels allegations from both Sunni radicals and Shi’ite opposition figures that Sunni veterans of the Afghan war carried out of character for the usually peaceful Shi’ite community. [16]

Despite American demands, Saudi Arabia has considered the Khobar Towers investigation complete since 1998 and refuses to send the imprisoned suspects to the US for trial. The Bush administration has likewise refused to extradite the large number of Saudi prisoners in Guantanamo Bay for interrogation and trial in Saudi Arabia. “Axis of Evil” member Iran returned 12 Saudi members of al-Qaeda to the kingdom in August, with the understanding that intelligence gleaned from their interrogations would be passed on to the US.

Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, with Shi’a zone highlighted (Stratfor)

Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, with Shi’a zone highlighted (Stratfor)

Saudi Arabia now finds itself under legal and financial attack in the US in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Saudi-based Islamic charities, banks and corporations are under close scrutiny by federal investigators, and many are named (together with three Saudi princes) in a $3 trillion class-action lawsuit filed in August 2002 by families of victims of the attacks. Some reports indicate that court documents show the Saudi regime paid $300 million in protection money to al-Qaeda in the late 1990s to prevent further terrorist attacks within the kingdom. At the same time, a senior official of the Saudi central bank was confirming that $200 billion in private Saudi investments had been pulled out of the United States in the spring and summer of 2002. [17]

Protectorates in the East?

The US is currently involved in an expensive effort to fill the nation’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) to its 700-million-barrel capacity. Filling the SPR is a preparation for a possible interruption in Saudi oil supplies in the event of disruption due to Iraqi retaliation for American attacks, or seizure of the anachronistic Saudi government by radical Islamists. With bases already in the area, how long can it be before the US declares Saudi Arabia’s oil-producing Eastern Province “a strategic necessity,” and proclaims a protectorate over the region?

In the event of a seizure of the Eastern Province the royal family might continue as rulers of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and a smaller kingdom. The Saudi Islamists take the rumours of American plans to partition Saudi Arabia seriously. Shaykh al-Awaji suggests that American military superiority will be met with suicidal resistance. Said he:

If America has intercontinental missiles and bombs, then our bombs are the Jihad fighters, whom American has called ‘suicide attackers’ and we call ‘martyrs.’ We will develop them because we see them as a strategic weapon.

There is some speculation that the Shi’a of the Eastern Province may welcome a regime change, particularly if the new government is secular and democratic. Although the Eastern Province is the source of the kingdom’s incredible wealth, revenues have been slow to filter down to the province’s Shi’a community. Infrastructure is poor and the region’s first modern hospital was not built until 1987. The Saudi regime expects loyalty from the Shi’a minority in return for shielding the community from the most extreme of the Sunni ulama, who press for the forcible conversion, deportation or execution of the Shi’ite kuffar (heretics). The Shi’a once formed one-third of the oil industry’s work-force, but have been dismissed under pressure from the Wahhabists. Many Shi’a would welcome the opportunity to get back into the petroleum industry and to find relief from Wahhabist animosity.

Old Enemies, Uncertain Future

An alternative to the division of the kingdom is to replace the Sa’ud family with members of the Hashemite clan. The Hashemites, former rulers of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, emerged from the First World War as rulers of the Hijaz (western Saudi Arabia) and the newly formed kingdoms of Iraq and Transjordan. The Hijazi Hashemites were deposed by ‘Abdul ‘Aziz ibn al-Sa’ud in 1925, their realistic British patrons “allowing events to take their natural course.” [19] The Iraqi Hashemites were overthrown in 1958, but the Jordanian branch of the family still governs, though it also faces the kind of criticism from Jordanian Islamists that Saudi Arabia’s royal family endures. At least three major Islamist plots against the government have been foiled by Jordanian security services in the last decade. Though the Hashemite option has its proponents, replacing one monarchy with another would represent a return to imperialist diplomacy of a century ago, and would ultimately do nothing to contribute to the stability of the region. Many of the 7,000 princes of the Sa’ud family have important positions in the Saudi security forces, access to the kingdom’s vast arms stores, and a willingness to defend their authority and privileges against their old Hashemite rivals. A Hashemite regime is unlikely to gain the approval of either establishment or radical ulama in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

In the 1980s, the Americans nodded approvingly as the call went out for Muslims to volunteer for jihad against foreign intervention in Afghanistan, and gave full encouragement to rich Saudis to donate money to the cause. Having helped to establish both the cause and the network that sustains it, the Americans must now address the anger created by their Saudi bases and their ongoing support for Israel’s obstinacy. Washington’s solution to the Saudi problem may be to bring Iraqi oil assets under American protection while lessening America reliance on Saudi resources. American interests are already exploring expansion into the largely untapped petroleum fields of Central Asia and the Caspian Basin. The “liberation” of Iraqi oilfields will have a punishing effect on the Saudi economy, driving more unemployed young Saudis toward radicalism while inhibiting the government’s ability to fund international Islamist causes. It will also have the effect of disrupting the patronage system that keeps the al-Sa’ud in power.

Although the Bush administration is still supporting the Saudi regime publicly, Saudis and Americans are looking at each other in a new light, and neither cares for what it sees.

Endnotes

- The RAND Corporation speaker, former Lyndon Larouche associate Laurent Murawiec, delivered a rather bizarre and poorly-received lecture on “Islamic Terrorism” at the University of Toronto last spring. The address consisted almost entirely of a discussion of ancient Chinese taxonomy, occasionally spiced with irrelevant quotations from 19th century German scholars. In the wake of the uproar caused by the later briefing to the Defense Policy Board, Mr. Murawiec’s resignation was received by the RAND Corporation in September 2002.

- Last June, the Saudis announced the arrest of an al-Qaeda cell planning attacks on American military installations within Saudi Arabia. A Sudanese veteran of the Afghanistan war led the cell of 11 Saudis and one Iraqi.

- Joseph Kechichian, “Islamic revivalism and change in Saudi Arabia: Juhayman al-‘Utaybi’s ‘Letters to the Saudi people’,” The Muslim World 80, 1990, pp. 1-16.

- For the information war in SA, see Brian Whitaker, “Losing the Saudi Cyberwar,” Guardian, February 26, 2001; “Islamic Psy-Ops,” from “The IW Threat from Sub-State Groups: an Interdisciplinary Approach,” by Dr. Andrew Rathmell, Dr. Richard Overill, Lorenzo Valeri, Dr. John Gearson: Paper presented at the Third International Symposium on Command and Control Research and Technology Institute for National Strategic Studies, National Defense University, Norfolk VA, June 17-20, 1997.

- ‘Abdullah bin Muhammad Al al-Shaykh, quoted in Milton Viorst, “The Storm in the Citadel,” Foreign Affairs, Jan-Feb 1996.

- Francine Dubé: “Family asks son in Saudi jail to cooperate,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), February 2, 2002.

- Prince Turki al-Faisal (Director, Saudi General Intelligence Department, 1977-2001), “The US and Saudi Arabia: A partnership that works,” Washington Post, September 18, 2001.

- Madavi al-Rasheed, “La couronne et le turban: l’état saoudien à recherché d’une nouvelle légitimité,” In: Bassma Kodmani-Darwish and May Chartouni-Dubarry (eds.), Les états Arabes face à la contestation Islamique, Paris, 1997, p.74.

- “Saudi Arabia faces pro-Taliban religious movement at home,” IslamOnline.net, Dubai, October 17, 2001, http://www.islamonline.net/English/News/2002-10/18/article11.shtml , 19/2/01.

- Shaykh Mohsin al-Awaji and Dr. Muhammad al-Khasif, quoted in “Saudi opposition Sheikhs on America, Bin Laden, and Jihad” (Transcript of a broadcast by al-Jazira TV, July 10, 2002), Middle East Media Research Institute Special Dispatch Series no. 400, July 18, 2002.

- Joshua Teitelbaum, “Holier than thou: Saudi Arabia’s Islamic opposition, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Papers no. 52, Washington, 2000, p. 77.

- “Saudi opposition Sheikhs on America, Bin Laden, and Jihad,” op cit, fn.10.

- Formerly known as the region of al-Hasa. The name was changed to the mundane “Eastern Province” to sever the historic connections between al-Hasa and the Shi’a community.

- The influential Wahhabist clergy regards Shi’ism as shirk (polytheism), and hence a heresy in Islam. The Saudi Shi’ite community is one of a number of Shi’ite groups found in the Gulf. The relatively powerless Shi’a majority in Iraq is the best known. Kuwait’s Shi’a minority has prospered, but the Shi’a majority in Bahrain has been involved in frequent and often violent protests against the Emirate’s Sunni regime.

- Much of the information alleging the existence of a “Saudi Hizbullah” was provided by the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS) at the deportation proceedings of Hani ‘Abd al-Rahim al-Sayigh, a Shi’a suspect in the attack.

- Graham E. Fuller and Rend Rahim Francke, The Arab Shi’a: The Forgotten Muslims, New York, 1999, pp. 179-201.

- Roula Khalaf, “Saudi downplays US investment selloff,” Financial Post (Toronto), August 23, 2002.

- Shaykh Mohsin al-Awaji, quoted in: “Saudi opposition Sheikhs on America, Bin Laden, and Jihad,” op cit, fn. 10.

- ‘Abd al-‘Aziz relied upon al-Ikhwan (“the Brotherhood”) for the military power needed for the al-Sa’ud to form the Saudi Kingdom. The Ikhwan were strict Wahhabists from the interior province of Najd, the home of the al-Sa’ud. They were disbanded by ‘Abd al-‘Aziz in 1927 as a threat to the stability of his new dual kingdom of Najd and Hijaz, later united in 1932 as the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. There are constant complaints from the other provinces of Saudi Arabia of “Nadji chauvinism” amongst the rulers of the kingdom, and some even complain that the name “Saudi” Arabia implies personal ownership of the Kingdom by the al-Sa’ud family.