Andrew McGregor

July 16, 2010

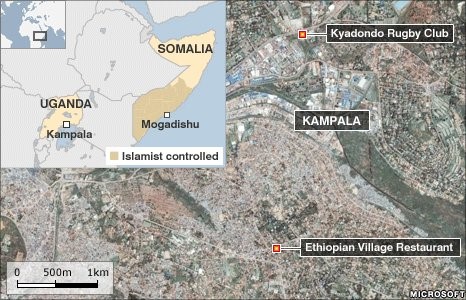

After several years of threats and warnings, al-Shabaab’s Somali jihad has finally spilled across Somalia’s borders to its East African neighbors. On July 11, bombs ripped through the Ethiopian Village Restaurant and the Kyadondo Rugby Club in Kampala, killing 74 civilians gathered to watch the World Cup finale. Somali Islamists have violently opposed the viewing of soccer matches in the past, saying the time could be better spent studying the Koran. Ethiopians are especially hated by al-Shabaab because of their country’s military occupation of Somalia from December 2006 to January 2009.

An estimated 5,000 people were in attendance at the rugby ground, which was reported to have little in the way of security arrangements (Daily Monitor [Kampala], July 13). The events have been termed suicide bombings, but there is emerging evidence, confirmed by al-Shabaab leaders, that the attacks were carried out by planting suicide vests that could be detonated remotely (New Vision [Kampala], July 13; Daily Nation [Kampala], July 13).

An estimated 5,000 people were in attendance at the rugby ground, which was reported to have little in the way of security arrangements (Daily Monitor [Kampala], July 13). The events have been termed suicide bombings, but there is emerging evidence, confirmed by al-Shabaab leaders, that the attacks were carried out by planting suicide vests that could be detonated remotely (New Vision [Kampala], July 13; Daily Nation [Kampala], July 13).

There is ample speculation that al-Shabaab is expressing its intention to join the global jihad with the Kampala bombings. However, the attacks are more likely to be part of a strategic plan to eliminate al-Shabaab’s strongest opposition to completing its conquest of Mogadishu and elimination of the TFG – the 5,000 African Union peacekeepers from Uganda and Burundi. The mandate of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) has changed since the first deployment of Ugandans in 2007. With no peace to keep, the mission’s mandate now provides for the vigorous military defense of the Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad government.

The bombings were carefully timed, coming a week in advance of the July 19-27 African Union summit meeting of heads of state, hosted this year by Kampala. More importantly, however, they come as a timely warning to the six member nations (Uganda, Sudan, Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti) of the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional grouping which responded to an urgent appeal from Somali president Shaykh Sharif Shaykh Ahmad by pledging on July 6 to provide an additional 2,000 men to AMISOM by September. Addressing worshippers at Mogadishu’s Nasrudin Mosque after prayers on July 9, al-Shabaab spokesman Ali Mahmud Raage accused the Somali president of handing the country over to the IGAD group of nations (Shabelle Media Network, July 9). Despite the decision, Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi made it clear that Ethiopian forces would not join the new deployment (AFP, July 7; PANA Online, July 6).

Al-Shabaab first issued threats of retaliation against Uganda for its contribution of troops to AMISOM in 2008. These threats culminated with a warning from al-Shabaab leader Shaykh Ahmad Abdi Godane “Abu Zubayr” on July 5 that “My message to the people of Uganda and Burundi is that you will be the targets of retaliation for the massacre of women, children and elderly Somalis in Mogadishu by your forces. You will be held responsible for the killings your ignorant leaders and your soldiers are committing in Somalia” (AFP, July 5).

After the bombings, Shabaab spokesman Ali Mahmud Raage described the attacks as “retaliation against Uganda” as he told reporters, “We thank the mujahideen that carried out the attack. We are sending a message to Uganda and Burundi, if they do not take their AMISOM troops out from Somalia, blasts will continue and it will happen in Bujumbura too” (Shabelle Media Network, July 12; Daily Monitor [Kampala], July 13; AFP, July 12).

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s resolve as AMISOM’s biggest backer to see the mission through is unlikely to be affected by the bombings, but the effect on support from a largely disinterested population will only begin to emerge after the official five day mourning period is over. For all of their military efforts in Somalia and now civilian losses at home, Uganda and AMISOM cannot turn the tide in favor of a transitional government that exists largely on paper. Most TFG parliamentarians and government leaders live outside the country, the president rarely emerges from the Presidential Palace, only blocks from the frontlines, and newly trained TFG troops desert with their rifles when they realize they are unlikely to be paid. Only a handful of tribal and religious militias with more interest in opposing the Shabaab extremists than preserving the TFG prevent AMISOM from being the lone defense of the TFG, a government that never found its footing and now survives only through foreign financial and military assistance.

More than 1,000 TFG troops are undergoing military training in Southeast Uganda by the European Union Training Mission (EUTM). The goal is to have 2,000 Somalis given basic training by the Ugandan army over the next year before receiving advanced training from the EU force. Salaries for the TFG recruits are being withheld until training is completed to prevent desertion (ABC.es [Madrid], May 31; El Mundo [Madrid], May 28; Nation Television [Nairobi], May 27).

Beyond the threat of al-Shabaab attacks, Bujumbura may soon find itself in need of its elite troops at home rather than in Mogadishu. Only six years removed from a brutal 12-year civil war, Burundi has endured almost daily grenade attacks in the capital and elsewhere in the weeks leading up to the re-election of sole candidate for the opposition-boycotted presidency contest, incumbent Pierre Nkurunziza (AFP, June 28).

Kenya responded to the attacks in Kampala by sending its elite General Service Unit to bolster defenses along its poorly secured 900 km border with Somalia (East African [Nairobi], June 14). The nation has received threats from al-Shabaab in the past for training TFG troops and harboring anti-Shabaab Somali politicians in exile. As part of its new policy on Somalia, Nairobi is urging the creation of a 20,000 man UN-AU hybrid peacekeeping force with full authority to combat al-Shabaab.

This article first appeared in the July 16, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor