Andrew McGregor

AIS Tips and Trends: The African Security Report

June 30, 2015

The conflict in Darfur continues to evolve in unforeseen ways due to government manipulation, arms proliferation, struggles over diminishing resources and seemingly unstoppable cycles of ethnic and tribal-based violence. In recent months the focus has shifted to a feud between two Arab tribes in East Darfur that has killed hundreds and displaced tens of thousands. Clashes between the Ma’aliya and Rizayqat began in 1966 over disputed land and intensified after 2007, leading to massive attacks with heavy weapons in which civilians are routinely targeted:

- In August 2013, fighting between the tribes killed 150 to 200 people and drove a further 51,000 from their homes (Sudan Tribune, August 31, 2014; Radio Dabanga, May 10, 2015).

- UN figures indicated that more than 300 Ma’aliya and Rizayqat were killed in fighting around the Umm Rakubah area of the Abu Karinka district in August 2014. The fighting was sparked by the theft of Ma’aliya livestock blamed on the Rizayqat (Sudan Tribune, September 1, 2014). As Rizayqat attacks continued, all Ma’aliya representatives in East Darfur state institutions resigned, citing Rizayqat dominance of these institutions (Sudan Tribune, September 21, 2014). The Ma’aliya also protested what they claimed was the participation of several government paramilitaries on the Rizayqat side, including the Border Guards, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the Popular Defence Forces (PDF) and the Central Reserve Police (a.k.a. Abu Tira).The RSF, effectively a reorganization of the notorious “janjawid,” are led in the field by Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti,” a Rizayqat from the Mahariya branch of the northern Rizayqat of Darfur.[1]

- The two tribes clashed near Abu Karinka on April 1 with the loss of 16 Rizayqat and four Ma’aliya after the alleged theft of 500 cattle from the Rizayqat and 600 sheep from the Rizayqat in the preceding days (Sudan Tribune, April 1, 2015).

- In late April 2015, the Rizayqat accused the Ma’aliya of attacking them in al-Fado (roughly 35 kilometers north of al-Daein), killing 20 people while stealing 650 head of cattle. The region’s breakdown in authority was displayed when two policemen were killed during pursuit of the raiders (Radio Tamazuj, May 1, 2015).

East Darfur state is a relatively new creation, having been formed from territory formerly part of South Darfur in accordance with the 2012 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD). The Ma’aliya, however, have officially boycotted participation in the new regional administration in response to the government’s failure to address attacks by Rizayqat gunmen, though a handful of Ma’ali individuals have agreed to participate as ministers and commissioners despite tribal opposition. One such is ‘Ali al-Sayid ‘Uthman Gasim, the state’s Minister of Social Affairs, who survived an assassination attempt by his one of his own relatives in mid-May (Radio Dabanga, May 14, 2015). The Ma’aliya are demanding the abolition of East Darfur state as a precondition to any peace agreement with the Rizayqat (Sudan Tribune, May 14, 2015).

Rizayqat Assault on Abu Karinka

After several days during which both Rizayqat and Ma’aliya gathered their forces around Abu Karinka, the two sides finally clashed in a violent struggle in the morning of May 11, 2015. Scores of people died, many when the Rizayqat attacked homes in Abu Karinka with missiles and other weapons. The Rizayqat “victory” may have been rather Pyrrhic, with heavy Rizayqat losses reported (Radio Dabanga, May 14, 2015). A Ma’aliya leader claimed the Rizayqat raiders used weapons and vehicles belonging to Border Guard units and the Rapid Support Forces (Radio Tamazuj, May 12, 2015). A Ma’aliya tribal leader, ‘Ali Muhammad ‘Ali, said that government military identification cards had been found on some bodies, while tribal spokesman Yusuf Hamid insisted Border Guards units participated in the fighting (Radio Tamazuj, May 13, 2015). According to the United Nations-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), the generally ineffective “hybrid” UN-African Union peacekeeping mission in Darfur, most of Abu Karinka was destroyed in the fighting, leaving a small number of civilians struggling to survive without power, food, water or fuel (Radio Tamazuj, May 15, 2015).

Following an emergency meeting of First Vice-President Bakri Hassan Saleh with Sudan’s intelligence director and the ministers of defense and the interior, a central government delegation was sent to El-Daien on May 12, but Rizayqat leaders refused to meet with it and a group of Rizayqat youth demanded the delegation leave the region within 24 hours (Sudan Tribune, May 12, 2015; June 2, 2015; Radio Tamazuj, May 28, 2015).

Mardas Guma’a, the speaker of the Ma’aliya Shura Council, complained that authorities had been notified by letter on May 7 that a Rizayqat attack on the Ma’aliya was imminent, but the government chose to supply government weapons such as “Dushka” machine guns (the Russian-designed DShK heavy machine gun), rockets and mortars to the Rizayqat militia. Guma’a singled out Sudanese second vice-president Hassabo Muhammad Abd al-Rahman (a Rizayqat) as a prime supporter of the Rizayqat militia (Sudan Tribune, May 14, 2015).

Shortly before the attack, Rizayqat deputy leader Mahmud Musa Madibbo accused the Ma’aliya of killing 11 Rizayqat tribesmen and stealing cattle during the February peace conference in Merowe. Madibbo further suggested that the Rizayqat were tired of government inactivity in restoring security in the region and were prepared to deal with the Ma’aliya themselves (Radio Tamazuj, May 11, 2015). Meanwhile, Ma’aliya tribal spokesman Yusuf Hamid declared that the Ma’aliya might turn to the International Criminal Court (ICC) if the government failed to implement justice in the region (Radio Tamazuj, May 18, 2015).

The Baqqara Arabs of Darfur

Baqqara Arabs on their Seasonal Migration

Baqqara Arabs on their Seasonal Migration

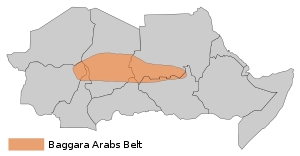

The pastoral Arabs of Darfur generally fall into two main groups, defined by the type of herding each group does, either camels (the northern aballa group) or cattle (the southern baqqara group). In southern Darfur, cattle have long proved more resistant to local fly-borne diseases than camels, thus determining the type of herds. In recent years this division has become less clear, with more northern Arabs migrating south (including the aballa Rizayqat) due largely to changing environmental conditions and the opportunity to seize lands from non-Arab groups displaced by the conflict in Darfur. The search for useful pastureland has led the Arab groups into conflict with indigenous sedentary populations in southern Darfur as well as semi-nomadic baqqara tribes. The Arab tribes of East Darfur have a core population based in towns and villages while young men take the herds on seasonal migrations in search of good pastures.

In practice, despite the often elaborate claims to descent from the noblest tribes of the Arabian Peninsula, the baqqara Arabs of Darfur are often physically indistinguishable from their “non-Arab” neighbors after centuries of intermarriage.

The Ma’aliya, who compose roughly 40% of the population of East Darfur, are centered on the town of Adila. The Ma’aliya were also involved in clashes with the Hamar tribe in May 2014 in the vicinity of al-Geraf in East Darfur. The fighting, in which at least 20 Ma’aliya were killed, began when Ma’aliya members took offence when a Hamar tribesman entered their territory looking for his stolen cattle. The Hamar tribesman returned with armed companions and began killing Ma’aliya (Radio Tamazuj, May 25, 2014).

The center of the baqqara Rizayqat is in al-Daein, the largest town in East Darfur state. The baqqara Rizayqat have been ruled by chiefs from the powerful Madibbo family since the 19th century, when the famed Musa Madibbo led Rizayqat resistance to the Fur sultans based in al-Fashir, often evading the Sultan’s punitive expeditions by melting into the southern swampland of the Bahr al-Ghazal region until the Sultan’s army was compelled to return to the capital. Since independence, the baqqara Rizayqat’s traditional leadership has supported the Umma Party of Sadiq al-Mahdi, who was overthrown as president by Colonel Omar al-Bashir (now president and wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes in Darfur) and the National Islamic Front of Hassan al-Turabi in 1989.

The center of the baqqara Rizayqat is in al-Daein, the largest town in East Darfur state. The baqqara Rizayqat have been ruled by chiefs from the powerful Madibbo family since the 19th century, when the famed Musa Madibbo led Rizayqat resistance to the Fur sultans based in al-Fashir, often evading the Sultan’s punitive expeditions by melting into the southern swampland of the Bahr al-Ghazal region until the Sultan’s army was compelled to return to the capital. Since independence, the baqqara Rizayqat’s traditional leadership has supported the Umma Party of Sadiq al-Mahdi, who was overthrown as president by Colonel Omar al-Bashir (now president and wanted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes in Darfur) and the National Islamic Front of Hassan al-Turabi in 1989.

Negotiations

A July 2014 effort by Second Vice-President Hassabo Abd al-Rahman to mediate between the parties was aborted when the Ma’aliya rejected his mediation due to his membership in the Rizayqat. Emissaries of the latter claimed that certain Ma’aliya representatives were actually members of other tribes (Sudan Tribune, August 31, 2014). The Ma’aliya accuse the vice-president of allowing the violence to continue and point to the Rizayqat’s use of sophisticated weapons similar to government stocks (Sudan Tribune, June 2, 2015). The largely Zaghawa Justice and Equality Movement (JEM – one of the most important and capable of Darfur’s rebel groups) has described Hassabo as a “warlord” who had been appointed by the president to lead a racial war in Darfur (Sudan Tribune, April 1, 2014).

As the two groups entered a second set of negotiations in Merowe in February 2015 with the mediation of first vice-president Bakri Hassan Salih, their positions were summed up by a representative of the East Darfur Rizayqat; according to Muhammad Issa Aliu, the Rizayqat claimed the Ma’aliya did not own any land in the area so the position of nazir (paramount chief) should belong to the Rizayqat, while the Ma’aliya claimed to own land in the region and thus demanded retention of the post of nazir awarded in 2003 (Radio Tamazuj, February 26, 2015).

Though the final document produced at the Merowe conference called for the retention of a Ma’aliya nazir, it also declared that the Adila and Abu Karinka areas belonged to the Rizayqat. Unsurprisingly, the document was immediately rejected by the Ma’aliya, though there is little doubt that the Rizayqat would have done the same had the decision gone against them. The main stumbling block was over interpretation of local hawakir (traditional land grants – sing. hakura), a system of land distribution started by 17th century Fur Sultan Musa bin Sulayman and continued under the Anglo-Egyptian administration (1916 – 1956).[2]

Sources of the Rizayqat-Ma’aliya Conflict

One source of the conflict lies in East Darfur’s tribal leadership. Formerly, the Ma’aliya had been under the formal leadership of the Rizayqat nazir (established by the Anglo-Egyptian administration of the 1930s), but in 2003 the Khartoum government created a new independent nazir for the Ma’aliya, a move rejected by much of the Rizayqat leadership who regarded it as a means of reducing the influence of the Rizayqat traditional leadership and the Umma Party, [3] particularly after the baqqara Rizayqat failed to respond to the government’s call for the formation of Arab militias (e.g., the “janjawid”) to combat the emerging rebellion of non-Arab tribes in Darfur (especially the Fur, Zaghawa and Masalit). Since then, however, government intelligence agents have used arms shipments and cash to encourage the development of a younger, alternative Arab leadership more amenable to Khartoum’s aims in the region.

The flow of arms to Darfur has increasingly been used to pursue Arab tribal agendas, even those involving competition with other Arab groups over access to water and pastureland. Arms proliferation in Darfur has reached the point that government security forces find themselves routinely outgunned by the feuding parties. The Ma’aliya, in particular, have complained that the absence of law enforcement is a contributing factor in the ongoing conflict (Sudan Tribune, June 1, 2015).

The discovery of oil in lands currently used by the Ma’aliya has naturally intensified the struggle over land ownership (Sudan Tribune, September 20, 2014). Ma’aliya chief Muhammad Ahmad al-Safi claims that compensation to local residents for environmental disruption has been unsatisfactory, while lack of employment opportunities in the oil fields has led to unrest amongst youth in the region (Gulfoilandgas.com, February 3, 2012). The China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and several smaller Arab firms are active in both exploration and production in Darfur. Despite enthusiastic estimates of massive reserves by Sudanese authorities (some five to fifteen billion barrels), these estimates appear to be exaggerated.

The Ma’aliya have also been involved in a bloody struggle with the Hamar tribe over ownership of the Zarga Um Hadid oil field in East Darfur, leading to a suspension in production in April 2014 (Radio Dabanga, April 6, 2014). The Khartoum government has become frustrated with the slow pace of oil exploration in Darfur and the interruptions created by local security issues. Having lost some 75% of its oil reserves with the separation of South Sudan in 2010, Khartoum is eager to replace fuel imports with local production that will also help finance government activities (Sudan Tribune, September 14, 2015).

Projections

The secretary-general of the Ansar (Mahdists, closely tied to the National Umma Party of Sadiq al-Mahdi), Abd al-Mahmud Abbo, asked in early June what has been achieved by the conflict in Darfur, “as ethnic hatred has spread throughout the region, resources have been destroyed, corruption has entered all levels of government and the door has been opened to foreign interference… neither the killer nor the slain know anymore why the killing occurred” (Radio Dabanga, June 3, 2015).

Khartoum may feel little need to intervene in the Rizayqat-Ma’aliya conflict and other tribal struggles over land and resources in Darfur. Many of the region’s Arabs are fed up with the Khartoum ruling class, which consists mostly of members of Sudan’s troika of powerful northern riverain Arab tribes; the Ja’alin, the Shaiqiya, and the Danagla. For the northern ruling group, the heavily Africanized baqqara Arabs are useful as agents of government policy but remain social inferiors unworthy of inclusion in any meaningful way in the central government. The mere fact that large-scale tribal battles continue to occur year-after-year in East Darfur does not speak to any commitment of resources by Khartoum, whose policy continues to be reactive rather than proactive. Rather, the government’s failure to address tribal rivalries in Darfur suggests that such conflicts aid in preventing the region’s baqqara Arabs from uniting against the center, or, even worse, allying themselves in large numbers with some of the region’s non-Arab rebel movements.

[1] The RSF comes under the direct authority of the National Security and Intelligence Service (NISS – Jihaz al-Amn al-Watani wa’l-Mukhabarat) and enjoys the patronage of Second Vice President Hassabo Muhammad Abd al-Rahman, a Rizayqat. For the RSF, see Andrew McGregor, “Khartoum Struggles to Control its Controversial ‘Rapid Support Forces’,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, May 30, 2014, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=852

[2] Mahmood Mamdani: Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror, Crown/Archetype, May 25, 2010, pp. 115-118. See also RS O’Fahey and J.L. Spaulding: Kingdoms of the Sudan, Methuen, London, 1974, where the hakura is defined: “An hakura may be defined as an estate, comprising usually a number of villages, less often a group of nomads, granted by the sultan to a member of his family, a title-holder or a faqih [religious authority]” (p. 157).

[3] See Jérôme Tubiana, Victor Tanner and Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil: “Traditional Authorities’ Peacemaking Role in Darfur,” United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC, 2012, p.19, http://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/traditional%20authorities%20peacemaking%20role%20in%20darfur.pdf