Andrew McGregor

Canadian Institute for International Affairs, Summer 1999

Confronted by separatist movements on several frontiers, the Chinese government watched with alarm NATO’s unsanctioned intervention in Yugoslavia. They needn’t have worried. There is little expectation of foreign support in Xinjiang, but the deeply divided Uyghur nationalists are determined to continue their struggle for autonomy.

The NATO air assault on Yugoslavia in support of the minority Kosovars has distressed the Chinese government which is trying to deal quietly with several minority movements of its own. Somewhere between the high-profile Tibetan independence movement and the virtually unknown separatists of Inner Mongolia is the Uyghur independence movement. The non-Chinese Turkic Uyghur people want independence for their traditional homeland of Xinjiang (or “Eastern Turkestan”), a mineral and petroleum-rich province in the northwest that covers one-sixth of China’s territory. Ever since Turkic Muslims displaced central Asia’s Indo-Buddhist civilization in the 11th and 12th centuries AD, Xinjiang has remained culturally Islamic.

Xinjiang

Xinjiang

Lying at the heart of central Asia, Xinjiang acts as a bridge for the extension of Chinese trade and economic influence, while it also serves as a security buffer between the Chinese and their Turkic and Persian Muslim neighbors. Some of the world’s most formidable mountain ranges surround the northern Zungharia region of northern Xinjiang, while the southern Tarim Basin contains the forbidding Taklamakan desert. Most Uyghur settlement is in the oases on the fringe of the desert, but there are also two small but economically depressed areas, the Ili Valley and the Turfan depression. The harsh terrain means that many regions exist in relative isolation and often possess different histories.

The modern use of “Uyghur” to designate the main group of Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang began only in 1924, when Soviet ethnologists used it to describe Turkic Muslim residents of the Soviet Union whose roots were in China. The term came into wide use after 1949, but many nationalists now prefer the old name of “Eastern Turkestan.” Whatever the designation, it should not be used to disguise the very real differences among the oases of the Tarim Basin or to imply a cultural and social unity that does not exist. Poor communications among Xinjiang’s population centers has meant that most oases historically look beyond the province for trade and cultural interaction. After the communist takeover in 1949, however, the city of Urumqi became a transportation hub for the rail exports of goods to eastern China. The province was also opened up to settlement by the majority Han Chinese.

Urumqi

Urumqi

Since 1949, Xinjiang has suffered almost continuously from ethnic division and a low-level insurrection that seems to be waiting for an opportune moment to blow wide open. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been vigilant in suppressing religious and political dissent, but the almost endless rounds of protests, mass arrests and executions have served only to keep the political pressure at boiling point. Since the early 1990s numerous small opposition groups have adopted violence in pursuit of independence. Assassinations, bombings and train derailments now accompany the more common street riots, demonstrations and attacks on ethnic Han Chinese.

In 1999, violence has become increasingly frequent, particularly in the separatist stronghold of the Ili Valley. In February, two leading Muslim separatists were executed in Yining City, while 1,000 crack troops were rushed in to dissuade retaliation. Because foreign correspondents and human rights organizations are generally barred from Xinjiang, the potentially explosive situation has an unusually low profile internationally. The absence of a high-profile spokesman (such as Tibet’s Dalai Lama) or a government in exile does not help, nor does the presence of a divided Uyghur opposition often consumed by personal feuds or such petty differences as what to call an independent Xinjiang. Some promote a “Greater Uyghurstan,” incorporating Xinjiang with parts of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Such dreams are not only unrealistic, they tend to ensure an unreceptive attitude among the central Asian states. The Islamic and pan-Turkic nature of the Uyghur separatist movement makes it generally unappealing to the Western social activists who have turned Tibet and even East Timor into international causes.

From Silk Road to Cultural Revolution

Xinjiang’s early history is revealed in the ruined cities of the famous Silk Road that ran through it, the great trading route that connected the Far East to the Middle East and beyond to Europe. There is ample evidence of Manichean, Buddhist and Nestorian Christian beliefs before the arrival of Islam. The province became part of the Chinese empire when Emperor Chen Lung defeated the ruling Zungarian Mongols in 1759. An independent Muslim khanate followed several minor revolts, and real Chinese authority came only with an invasion by the Manchu Qing dynasty in 1876. Resistance to Chinese rule continued under the republican government, with a short-lived Turkish-Islamic Republic of East Turkestan established around Kashgar. Massacres of Chinese, Hindus and Christian missionaries followed, until the nation was destroyed by the Soviet Union in 1934 at China’s invitation. During the republican period, ethnic-Chinese Muslims (Hui) enjoyed great power in Xinjiang as soldiers and administrators. Rebellions began to take on an anti-Hui character, especially after the republican leader, Chiang Kai-Shek, argued that all minorities were branches of the Han family.

Xinjiang’s Turkic Muslims took advantage of the turmoil of the Second World War to found the East Turkestan Republic (ETR), which lasted from 1944 to 1949. Having grown out of the Uyghur and Kazakh “Ili Rebellion,” the ETR government was multi-ethnic. At the time, Mao Zedong was promoting autonomous rule for Chinese minorities to win support for the CCP. After most of the ETR leadership died in a mysterious plane crash en route to negotiations with the CCP in Beijing, Xinjiang was reoccupied and brought under communist control as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. [1] Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76) was a devastating period for the Turkic population as mosques were closed, books were burned, hard labor camps created and religious leaders arrested. More than 100,000 Uyghurs and Kazakhs escaped to the Soviet Union; others fled to Turkey, Germany, Taiwan, India, Afghanistan and Australia. A more lenient religious and cultural policy in the 1980s only encouraged the growth of nationalism.

The Mummies of the Tarim Basin

As in other ancient but disputed territories, archaeology has found itself at the center of territorial claims. In 1979, Chinese archaeologists began uncovering large numbers of well-preserved Caucasian “mummies” in Xinjiang Province, all of which appear to have belonged to an advanced Indo-European culture. A number of Uyghur nationalists, led by Turghan Almas, an officially banned historian, identify the mummies with the ancient culture of the Tarim Basin, as preserved in Uyghur folklore. The carbon-dated remains have been used to substantiate Uyghur nationalist claims that, not only were their ancestors the ancient inhabitants of Xinjiang, but their civilization was substantially older than that of the Han Chinese. The ancient Uyghur culture, language and script have always held the highest reverence in the Turkic nations across Asia as the earliest manifestations of Turkic civilization.

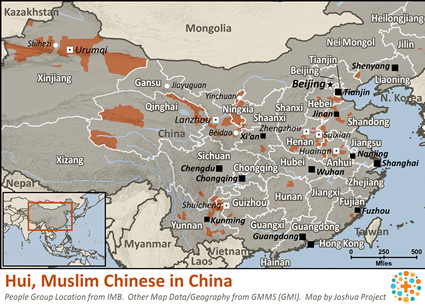

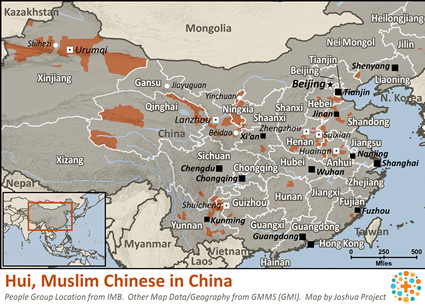

China’s Other Muslims

China has at least 20 million Muslims organized into at least ten ethnic groups. [2] Of these, only the Uyghur and the Hui are significant in terms of numbers. (The Chinese always distinguish between the Hui or “common Muslims” and the Turkic or “turbaned Muslims”). The approximately 9 million Hui – Han Chinese converts to Islam – are found throughout China, but particularly in Gansu and Ningxia provinces. Historically, many Hui in Xinjiang have been soldiers, administrators and even warlords, but they command little respect from the Uyghurs. Though the Hui and the Uyghurs are unlikely to make common cause, the Hui have also proven turbulent subjects at times; serious disturbances erupted in 1992-93 in Ningxia province when local government officials attempted to interfere with the Khufiya Sufi order.

The vast majority of Muslims in China are orthodox Sunnis (the mainstream of Islamic thought). Because Sunni Sufi orders pursue a mystical path of worship, they are seen as potential breeding-grounds for Islamic extremism. They flourish nonetheless in Gansu, Ningxia and Qinghai, as well as in Xinjiang. Similar orders helped keep Islam alive during the communist occupation of the Muslim states of the Caucasus and central Asia.

The vast majority of Muslims in China are orthodox Sunnis (the mainstream of Islamic thought). Because Sunni Sufi orders pursue a mystical path of worship, they are seen as potential breeding-grounds for Islamic extremism. They flourish nonetheless in Gansu, Ningxia and Qinghai, as well as in Xinjiang. Similar orders helped keep Islam alive during the communist occupation of the Muslim states of the Caucasus and central Asia.

Hui Muslim Girls

Hui Muslim Girls

The Islamic Opposition

CCP efforts to restrain Islamic practice by closing mosques and Islamic schools create an opening for more extreme forms of Islam to penetrate the rather moderate Sunni-style Islam of the Uyghurs. Chinese attempts to control Muslim clerics are unpopular; in March 1996 a pro-government religious leader was assassinated in Xinjiang.

The Uyghur nationalist opposition is deeply divided. At least 20 distinct groups (mostly exiles from the Uyghur diaspora [3]) range from “letterhead” organizations to guerrilla groups running terrorist/low-level insurgency operations. The most prominent and credible of the exiled leaders is Erkin Alptekin, son of the former secretary-general of the ETR. He is the current chair of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO), formed in 1989. [4] His father, the late Isa Yusuf Alptekin, joined with Tibet’s Dalai Lama in 1985 to found the Allied Committee of the Peoples of East Turkestan Tibet and Inner Mongolia, a group which organizes demonstrations and conferences to publicize alleged Chinese human rights violations. The movement, which favors dialogue over violence, is frustrated by Chinese refusals to talk with any “splittist” organization.

Attempts to build a cohesive nationalist consensus among Xinjiang Uyghurs have also been frustrated by what Justin Rudelson, a central Asian scholar, has called “oasis chauvinism.” Uyghur identity tends to be closely tied to the oasis of origin, be it Kashgar, Yarkand, Karghalik or Turpan. Each nationalist “attempts to create a nationalist ideology which places his own oasis at the forefront of Uyghur history in order to facilitate the acceptance of a national identity at the oasis level.” [5]

New States, New Policies

The collapse of the Soviet Union introduced five new central Asian states to the world community – Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. All were Turkic-Muslim in character, save Tajikistan, where the majority language and culture has Persian roots. Though the Uyghurs are the last significant Muslim group under communist rule, they have received little encouragement from their central Asian cousins. Aside from Askar Akayev of Kyrgyzstan, the current central Asian leaders are all former members of the Soviet communist elite and are unlikely to support any activity that could threaten their positions. Pan-Turkic nationalism and Islamic sentiment played no role in the independence of these states, which were virtually cast off by a re-organizing Russia. Continued Russian influence, particularly in security matters, is another factor in discouraging activities which might threaten Russian-Chinese relations in what both nations would concede is a historically sensitive area. The damage to Islamic life and tradition over 70 years of communist rule in the ex-Soviet central Asian states makes a home-grown Islamic movement of any strength in the area (other than Tajikistan) unlikely in the near future.

Uzbekistan, the largest central Asian state, is the most fervently anti-Islamist. According to President Islam Karimov: “Such people must be shot in the head. If necessary, I’ll shoot them myself.” [6] In 1996, China used its economic power to pressure Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan into signing the Shanghai Accords, essentially an agreement to repress Uyghur separatists and other Islamic movements in any of the signatory countries. Karimov claims that recent bombings in which 16 people were killed in Tashkent were the work of Uzbek Islamists trained in Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Kyrgyzstan has long-standing border ties with Kyrgyz communities in Xinjiang and with Uyghurs in Kyrgyzstan. In 1990, the Chinese subdued what they described as a “counter-revolutionary rebellion” led by Kyrgyz preparing for a jihad against Han Chinese, [7] and in 1998 a number of Uyghurs were arrested in Kyrgyzstan for “Wahhabist” activities. Because Kyrgyzstan is worried about the state of its relations with China, Uyghur exiles have been warned not to use it as a base for separatist activities. Like the other new states of central Asia, Kyrgyzstan is concerned about maintaining relations with China now that it can no longer count on Moscow’s might in support of decisions affecting cross-border ethnic ties.

With a population of 300,000 Uyghurs, Kazakhstan is most sensitive to potential difficulties with Beijing. Many of the urban “Russified” Kazakhs look to their Uyghur relatives in Xinjiang for authentic Turkic culture. After Kazakhstan signed a border agreement with China in 1994, the offices of several Uyghur nationalist groups in the capital of Almaty were closed. In 1998, Kazakhstan extradited two Uyghur mullah-s (Islamic teachers) and their families who had fled from Xinjiang. Chinese-Kazakh trade totals more than that of Turkey with all of central Asia, and the Kazakhs are currently engaged in joint ventures with the Chinese National Petroleum Company (CNPC) to develop Kazakhstan’s extensive energy reserves. Nonetheless, Kazakhstan has been a source of concern to China since it hosted military manoeuvres involving American troops as part of NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme. Because the Kazakh government also fears Islamist movements, it formed an alliance with Russia, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan against “Wahhabist extremism.”

Although China would find it difficult to project its military power westwards into central Asia to suppress any cross-border support for a Uyghur insurrection, it may count for the moment on central Asia’s leaders to do the work for it.

Islamic Extremism?

The post-communist governments of central Asia are alarmed by any sign of “Wahhabist” activities, a reference to Islamist activists who take their inspiration from Wahhabism, a highly conservative religious revival movement founded in Arabia in the mid-18th century by Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab. The puritan movement became closely tied to the al-Sa’ud family, who eventually conquered most of the Arabian Peninsula. The Wahhabists (who prefer to be called Muwahhidun or Unitarians) reject any Islamic trend that interfered with the direct contemplation and worship of God. Wahhabist control of the holy cities of Saudi Arabia allows the movement to spread its influence amongst Islamic pilgrims, including those from Xinjian and central Asia. The use of jihad to establish an Islamic state is central to Wahhabist doctrine. The degree of Wahhabist influence in central Asia is difficult to gauge, as the term is often used by various governments to describe any militant Islamist group so as to justify extreme measures against them. China rarely uses the term in official declarations, probably in deference to Saudi Arabia, with whom China needs to maintain good relations because of its energy needs.

Terrorism, often described as the weapon of the powerless, has erupted in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China – allegedly the work of Uyghur nationalists. In 1997, there were bus bombings in Urumqi and Beijing. The latter was especially embarrassing to the Chinese government because it coincided with the funeral of Deng Xiaoping. The Organization for Turkestan Freedom, which has its headquarters in Istanbul, claimed responsibility for the bombings, which came only a day after punishments for terrorism were increased and new charges of “inciting ethnic hatred” and “taking advantage of religious problems to instigate the splitting of the state” were added to the criminal code.

Many Uyghurs were arrested and executed, but a statement from the UNPO questioned Uyghur participation: “We now believe that the Chinese authorities or some elements within the government may have set off the devices… to discredit the Turkic peoples of East Turkestan, and to create a pretext for even more severe repression in our region.” [8] The accusation is unlikely; the bombings brought world media attention to Xinjiang’s problems, and what the CCP fears more than anything is internationalizing the issue.

Language and Demographic Issues

At the core of Beijing’s attempts to pacify Xinjiang is a campaign to create a major demographic change in the ethnic proportions of the province’s population. When the CCP took control of Eastern Turkestan in 1949, Han Chinese [9] made up only five per cent of the population. With 300,000 arriving every year, the Han Chinese are now as numerous as the Uyghur, and there are plans to being many more settlers. A more liberal reproductive policy which allows two children per couple rather than one as in the rest of China encourages Han resettlement in Xinjiang. There are also plans to accommodate many of the up to two million people who will be displaced if the Three Gorges dam project proceeds.

Language is a major barrier between Muslims and Han Chinese, who live highly segregated lives in Xinjiang. While some Uyghurs may learn Chinese to facilitate trade, it is almost unheard of for Chinese to learn Uyghur or any other Turkic language. Most education in the province is in Chinese. The few Uyghurs who attain higher education can expect little in the way of employment opportunities; most of the preferred jobs are reserved for ethnic Chinese. Those works on Uyghur history and culture that are written in Chinese are all dedicated to proving the historical unity of the Uyghur and Chinese races. CCP intervention in Uyghur language issues has proved disastrous. The traditional Arabo/Persian script used for Uyghur was for twenty years replaced by the Pinyin Latin script before a reversal of CCP policy rendered a generation of Uyghurs illiterate in their own language.

Administrative Mechanisms

In the 1950s, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) began an experiment with a “Production and Construction Corps,” a paramilitary force responsible for border defence and internal security, along with normal duties in agriculture and construction. The Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC) is the only one still active. Run independently of the regional government, the XPCC has considerable autonomy and legal jurisdiction through its own police, courts and prisons and is a constant irritation to the Uyghurs. It diverts most of the available water for its irrigation schemes and pollutes the remainder with industrial waste. Land annexation is common and Uyghur farmers are often forced into agricultural “regiments” of the XPCC. As part of its internal security responsibilities, the XPCC rather than the PLA increasingly responds to riots and other disturbances. XPCC units were a major part of the 1996 “strike hard” campaign against “ethnic splittists” (the CCP term for minority separatists), carrying out mass arrests after meeting armed Uyghur resistance.

Communist Demolition of Mosques in Xinjiang (VOA)

Communist Demolition of Mosques in Xinjiang (VOA)

China maintains an extensive network of prison camps in Xinjiang which receive thousands of criminals each year from all over China. After completing their sentences, the convicts are forbidden to leave the province, but are welcome to send for their families. Many Uyghurs blame rising crime rates on the presence of the hard-labor camps. In 1996, a leading Chinese dissident, Harry Wu, and Erkin Alptekin testified before a US senate subcommittee that the XPCC was using World Bank funds to build penal colonies.

Nuclear Testing and Petroleum Extraction

Another volatile issue is the ongoing programme of nuclear testing in the Taklamakan Desert. Protests against testing began in Xinjiang in 1985, and Uyghur émigré associations claim over 200,000 people have died from nuclear fallout. Illnesses and birth defects like those experienced by the victims of Soviet nuclear tests in neighboring Kazakhstan have been reported. While the Kazakhs are now receiving direct UN aid, the Uyghurs are still awaiting an investigation.

Chinese Oil Operations in the Tarim Basin (Upstream Online)

Chinese Oil Operations in the Tarim Basin (Upstream Online)

China’s determination to open up the oil resources of Xinjiang comes at a time when the nation has become a net importer of oil, but the reserves in the Tarim Basin are extremely difficult to tap. Though the experience of Western-based oil consortiums is essential, poor concessions and exorbitant fees have discouraged several companies. Worst of all is the lack of discoveries to support China’s estimates of 80 to 180 billion barrels of oil in the Tarim Basin. As estimates fall sharply, the attention of world oil companies has moved on.

International Implications

With its sovereignty challenged in Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and Taiwan, China is clearly alarmed by NATO’s unsanctioned military support of an internal rebellion in a sovereign nation, Yugoslavia. American strategic and economic interest in Kosovo is negligible; Taiwan, however, is another matter, and China fears a resumption of the pre-détente US/Taiwan military relationship. Chinese premier Zhu Rongji has even warned of the possibility of world war if the principle of non-intervention is not carefully observed in international law and conflict. [10]

The problem of Tibetan independence was raised repeatedly during Zhu’s visit to Canada in April 1999, but the lower profile problem of Uyghur separatism was not. Despite the continuing violence in Xinjiang, and to a lesser extent in Tibet, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien supported Zhu’s assertion that China’s minority difficulties were an internal affair: “There are no murders. We don’t have the rapes that we’re seeing right now in Kosovo. Those are two completely different positions. One is political, the other one is extremely violent.” [11]

With Chinese-American relations already strained over several issues, there is little political interest in Washington in inflaming relations by supporting Islamic minority rights in China. Closer to home, China maintains close ties with Pakistan and Iran, largely designed to counter the spread of radical Islamic movements from those countries. Pakistan has often been cited by the Chinese as the source of weapons for Xinjiang’s most militant nationalists, and they did not hesitate to ask Pakistan to crack down on a Muslim group suspected of smuggling arms to the Uyghurs. The Arab nations of the Middle East also want to maintain good relations with China, a major regional arms supplier.

Conclusion

With no expectation of substantial assistance or recognition from foreign sources, the Uyghur separatists have limited options; an extended terrorism campaign (which may get some international press but is unlikely to gain international support), a negotiated settlement (unlikely, as China refuses to talk to “splittists”), or an all-out revolt, as in Chechnya. Unlike the Chechens, the Uyghurs have little military experience to draw upon, while the PLA would have almost unlimited resources and manpower at its disposal from a strongly centralized state facing no major opposition.

China would be most reluctant to relinquish control of Xinjiang, which it needs for its energy resources, as a base for China’s still active nuclear weapons programme, as a security buffer to central Asia, and as a destination for China’s ongoing population resettlement. Most importantly, Xinjiang’s separatist movement does not exist in a political vacuum. Any sign of weakness on Beijing’s part could be interpreted as a sign for Tibet and Inner Mongolia to set up their own independence campaigns and cause serious problems for China’s effort to reunite Taiwan into the mainland fold. As in many post-communist states in Europe and Asia, nationalism and economic reforms have been used to keep multiethnic states together. The Uyghurs themselves have suggested that Beijing has deliberately exaggerated the militancy of the Uyghur nationalist movement in order to create an “internal enemy” around which the CCP can build strong nationalist sentiments amongst the Han Chinese at a time when economic and external pressures threaten the solidarity of the Chinese union. An emphasis on the threat of Islamic “fundamentalism” also serves to keep most Western governments at bay.

Some Uyghurs believe that only the collapse of the People’s Republic would create an opportunity for East Turkestan to secede, but others have become desperate in their belief that every new trainload of settlers makes independence a little more remote. Knowing that time is against them, it is clear that any serious drive for independence must be made sooner rather than later. Addressing their lack of international support, Ahmedjan Qari, a leading Uyghur nationalist exile, has warned that “The world doesn’t think we will die like in Afghanistan, like in Yugoslavia. We can. We will die in droves.” [12]

Endnotes

- There are five “autonomous regions” in China – Tibet, Mongolia, Ningxia, Guangxi and Xinjiang – which in practise often enjoy less autonomy than their non-autonomous neighbors.

- There are five Turkic Muslim groups in Xinjiang: Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks and Tatars. There are also the Persian-speaking Tajiks and, in the region bordering Gansu and Qinghai provinces, the Salars (who speak a Uyghur dialect) and the Bao’an and Dongxiang, who both speak an archaic Mongolian language. The Hui, ethnic Chinese with a long Muslim tradition, are the tenth group. The language used by the Hui is Chinese, peppered with Arabic and Persian loan-words.

- There are Uyghur communities and exile organizations in Istanbul, Ankara, Almaty, Amsterdam, Munich, Melbourne and Washington DC.

- “Participation in UNPO is open to all nations and peoples who are inadequately represented as such at the United Nations.” At present, 52 “nations or peoples” have declared adherence to UNPO’s five principles.

- Justin Jon Rudelson: “The Xinjiang mummies and foreign angels: Art, archaeology and Uyghur Muslim nationalism in Chinese Central Asia,” in M. Gervers and W. Schlepp (eds.), Cultural Contact, History and Ethnicity in Inner Asia, Joint Centre for Asia-Pacific Studies, Toronto, 1996, p. 173.

- See: “Republic of Uzbekistan: Crackdown in the Farghana Valley: Arbitrary arrests and religious discrimination,” Human Rights Watch 10(4D), May 1998.

- Lillian Craig Harris: “Xinjiang, central Asia, and the implications for China’s policy in the Islamic world,” China Quarterly no. 133, March 1993, pp. 117-18. Jihad is a complex concept that involves a militancy on behalf of Islam that can take many forms based on interpretations of the Koran and the hadith-s (sayings of the Prophet). In general, the “greater jihad” is the struggle against the evil within oneself, while the “lesser jihad” is the effort to bring Dar al-Harb (areas outside of Islam) within Dar al-Islam (the “House of Islam”).

- UNPO, “Bombings will be used as pretext for severe repression in East Turkestan,” May 27, 1999.

- While there are no less than 70 million belonging to ethnic minorities in China, the Han Chinese still comprise about 94% of the population. “Han” is a cultural rather than a racial designation in that its use disguises the significant linguistic and physical differences that exist across China. The CCP has encouraged the use of the term to foster national unity.

- Miro Cernetig: “Chinese leader warns of global war,” Globe and Mail, Toronto, April 3, 1999.

- Heather Scoffield: “PM and China’s Zhu take heat on rights,” Globe and Mail, Toronto, April 17, 1999.

- Quoted in Tony Walker and Charles Clover: “Bombs rock China’s far west: Islamic militants put Uighur nationalism on the map with terrorist blasts,” Financial Times, London, February 27, 1999.

This article first appeared in the Summer 1999 issue of Behind the Headlines: Canada’s International Affairs Magazine, Canadian Institute of International Affairs, Toronto.