Part Two – Can Russian Military Contractors Overcome Tribal Politics and French Influence in the CAR?

Moscow’s Privatized Point-Men in Central Africa Have Had It Their Way So Far. Can It Last?

Dr. Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, February 5, 2022

Moscow’s addition of Russian “contract soldiers” to its fighting force in Chechnya has evolved into the regular use of contract fighters to spread Russian political and economic interests in conflict zones, especially those experiencing seemingly intractable conflicts. Unlike those who served in Chechnya, the new generation of contract fighters operate outside Russia’s formal military structure. Like earlier European mercenary groups in Africa, it is understood by the leaders of these “contractors” that their reward for saving governments under threat will be guaranteed access to the wealth generated from resource extraction.

Central African Republic (Worldometer)

Central African Republic (Worldometer)

The use of mercenaries as bodyguards for the president has a long history in the CAR, with Chadian gunmen usually filling this role, so the introduction of Russian mercenaries as presidential security was hardly unprecedented. What is surprising is the eagerness with which African nations such as the Central African Republic (CAR), Sudan, Mozambique, Mali and others have welcomed the return of White European mercenaries after decades spent trying to drive them out of Africa. The surprise is even greater when it is plain the mercenaries from the east are still using the playbook used by the White mercenaries of the 1960s and later:

- Separate the ruler from the ruled by forming a bodyguard of mercenaries who control access to the leader;

- Insert economic “advisors” who direct national finances;

- Ensure rights to mining and other extractive industries are given to firms favored or owned by the mercenaries;

- Establish discreet and deniable connections to European states or corporate interests seeking to establish or expand their influence and holdings in Africa.

The leaders of Wagner Group appear to be familiar with the work of earlier European mercenaries in Africa, including Frenchman Bob Denard, a mercenary who worked for Belgian mineral interests in Katanga in the 1960s. Denard later became the power behind the throne in the Comoros Islands by controlling its 500-man presidential bodyguard through the 1980s, maintaining connections to Jacques Foccart, France’s point-man in Africa before deciding to take over the country himself in 1995.

The Russians are also sure to have studied the disastrous South African deployment in Bangui in 2013 and the book Composite Warfare: The Conduct of Successful Ground Force Operations in Africa, an influential 2016 tactical work by South African mercenary Colonel Eeben Barlow, based partly on operations carried out against Boko Haram in Nigeria by his mixed-race “Specialized Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection” unit (STTEP). [1]

Civil War in the CAR

Both Ali Darassa and Mahamat al-Khatim were officially dismissed as special military advisors on December 31, 2020 (RFI, January 2, 2021). Al-Khatim’s Mouvement patriotique pour la Centrafrique (MPC) suffered serious losses in arms and personnel during the late 2021 government counter-offensive. A recent communiqué from the MPC chief-of staff, “General” Abdraman Mahamat Abfiessa, accused the government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, a Christian, of “using a Hitlerian strategy to erase the Muslim identity of the Central African Republic” (Corbeau News [Bangui], January 7, 2022).

Sidiki Abass, whose Retour, Récupération, Réhabilitation (3R) militia was notorious for torture, rape and murder, quickly returned to the bush after the 2019 Khartoum Accord that was meant to end the fighting. He died in March 2021 from wounds either received in an attack on a village on November 16, 2020 or in an ambush of his convoy in December 2020. Sidiki was succeeded by the self-described “General Bobbo.” The 3R’s hold on diamond-rich areas and control of the cross-border cattle trade with Cameroon have enabled it to buy arms and recruit mercenaries of their own (Vanguard [Lagos], December 6, 2021). Many of these mercenaries come from Chad, some with combat experience on Libyan battlefields. There is no difficulty for them in crossing the permeable border between Chad and the CAR.

3R is mostly Fulani, as is the UPC, and began its run in 2015 as a Fulani self-defense militia. Al-Khatim’s MPC is a mix of Arab and Fulani fighters. The conflict in the northern CAR reflects the growing militancy of the Fulani people across Africa’s Sahel belt, though their struggles remain uncoordinated, lack central direction and are generally fuelled by local issues and ethnic rivalries rather than ideology. Baba Laddé is one of the few to have tried to situate the violence between Fulani groups and their neighbors within a larger ethnic framework, with some attempt to define larger goals for a multinational Fulani alliance.

Fulani herders in the CAR are actually targeted by both certain rebel groups and government forces (and their allies), whether through taxation in the form of cattle or retaliatory attacks in response to operations by self-identified Fulani “self-defense” groups. In dealing with the Fulani, the Russians are reported to make little distinction between civilian herders and armed fighters (Le Monde/AFP, January 14, 2022).

The ongoing violence in the CAR began when its president, François Bozizé Yangouvonda (Gbaya ethnicity), was deposed in March 2013. Bozizé had seized power in a 2003 coup but was expelled by the Muslim Séléka alliance of Arab and Fulani rebel groups in 2013. Bozizé fled Bangui for Cameroon in March 2013 as Russian-educated Séléka leader Michel Djotodia took power as the CAR’s first Muslim president. Bangui and other parts of the CAR were plunged into violence as hastily-formed “anti-Balaka” Christian militias began retaliatory attacks on Séléka fighters and Muslim civilians for attacks on CAR Christians.

Djotodia, a member of the Gula ethnic group from Vakanga prefecture, was forced to resign in January 2014 and an interim government was formed as UN, African Union and French troops attempted to restore stability and security. In March 2016, academic and former prime-minister Faustin-Archange Touadéra was elected CAR president. Following the election, French troops withdrew, creating immediate security challenges for the new president.

Bozizé attempted a return to the CAR in late 2019 with the intention of running in the December 2020 presidential elections, but the CAR’s constitutional court announced his disqualification on moral grounds due to outstanding international warrants and UN sanctions for torture and war crimes. Instead, Bozizé was alleged to have mounted a failed coup attempt in December 2020, a week before elections were to begin. The action prompted Russian and Rwandan reinforcements.

Six of the strongest rebel groups mounted a joint offensive against the Touadera government in December 2020, calling themselves the Coalition des Patriotes pour le Changement (CPC). Their plan to cut off the capital was foiled by the response of CAR troops, Rwandan special forces and Russian mercenaries. By January 13, the rebels began to retreat. Ten days later, the government reported the death of 44 rebels at Boyali (54 miles from Bangui), “including several mercenaries from Chad, Sudan and the Fulani.” (Al-Jazeera, January 25, 2021).

In late February 2021, the Bozizé stronghold of Bossangoa 175 miles north of Bangui was captured by CAR troops supported by Russians and Rwandans. Bozizé, who was being investigated for “rebellion” at the time, took charge of the CPC in March 2021. He is now believed to reside in N’Djamena; in his absence, Ali Darassa has taken control of the rebel coalition.

The CAR government declared a unilateral ceasefire in October, 2021 to encourage a dialogue with rebel factions. The move, however, had little impact on the ongoing violence; the rebels had little interest and the government offensive continued. 3R forces attacked the town of Mann in the northwest, killing five civilians and one soldier in December 2021, while a particularly gruesome machete attack by pro-Touadéra militias in the CAR’s center-east left 15 civilians dead including women and children; many others suffered mutilations and amputation of limbs (AFP, December 20, 2021; ).

Increasing the instability in Bangui is the revival of the Requin (“sharks”), a pro-ruling party militia known for its violence. Created in 2019 by Touadéra’s Mouvement cœurs unis (MCU – United Hearts Movement), the Requin were dissolved in July 2020 under international pressure. Resurrected in 2021, the group mounts heavily-armed patrols through Bangui at night (Jeune Afrique, January 12, 2021). They have been accused of mounting an assassination campaign against members of the Gbaya (François Bozizé’s ethnic group) and circulating lists of opposition figures to be eliminated (Corbeaunews [Bangui], January 18, 2021). Russian mercenaries are also reported to have targeted the Gbaya with summary executions (ICG, December 3, 2021).

Clashes on the Chad/CAR Border

Unsurprisingly, tensions between a pro-French government in Chad and a pro-Russian government in Chad’s traditional Central African hinterland have created a state of instability along the border between the two nations. At times, these clashes have threatened to spark a wider conflict.

An attack by Russian fighters and CAR regulars on a Chadian border post on May 30, 2021 resulted in the death of six Chadians and three Russians. Chad’s defense ministry claimed that five of their soldiers had been captured and executed. Bangui insisted the clash was “a mistake” resulting from CAR forces and their allies pursuing rebels near the border (Reuters, June 2, 2021). A diplomatic crisis followed and more Chadian troops and weapons were sent to the border. The incident came only weeks after the Russian ambassador to the CAR criticized Chad for failing to prevent the passage of arms and fighters across the border into the CAR (Africa Report, June 4, 2021). Asked why Chad did not respond militarily to the execution of its troops, Mahamat Idriss would only respond: “Let’s just say that we exercised a lot of restraint after these murders were committed” (Africa Report, June 30, 2021).

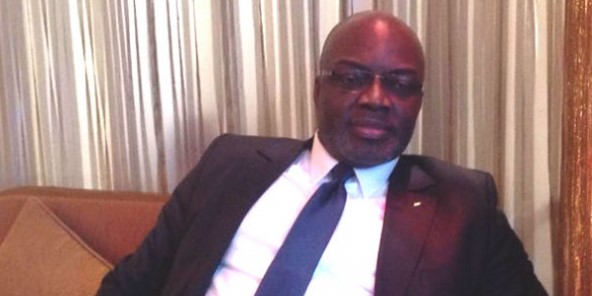

Following the incident, the CAR’s top “fixer,” Sani Yalo, was sent to N’Djamena to assure Chad’s leadership that President Touadéra had no interest in creating insecurity on the border. Yalo is a political operator and one of President Touadéra’s closest advisors, despite having no official position. Believed to be pro-Russian, Yalo has demonstrated his survival skills and importance by acting as a presidential advisor during the presidencies of Ange-Félix Patassé, François Bozizé and Michel Djotodia. Touadéra refuses to extradite Yalo to Equatorial Guinea, where he is wanted for his alleged involvement in a 2017 attempt to overthrow President Teodoro Obiang Nguema (Jeune Afrique, October 16, 2019).

A further confrontation followed on December 10, 2021, when Russian mercenaries pursuing CPC rebels crossed the border into Chad. After a firefight with Chadian troops in which one Chadian was killed, the Russians withdrew, taking one captured soldier with them (Corbeau News, December 12, 2021).

Instability on the CAR’s South-Western Border with Cameroon

The regions adjacent to the 560-mile-long border between Cameroon and the CAR are beset by cattle-rustling, banditry, kidnappings and arms trafficking. When pressed, rebel groups from either nation take refuge on the other side of the border and have become heavily involved in resource exploitation, including the hunt for gold. Life in the border region has become precarious; 3R rebels launched attacks on CAR civilians and security forces near the Cameroon border on November 28, 2021, killing 30 civilians and two soldiers.

It is not only Fulani herders who are now in conflict with agricultural communities. In northern Cameroon, there have been repeated and bloody clashes between Arab Shuwa herders and Musgum (a.k.a. Mulwi) and Masa (a.k.a. Masana, Yagoua) farmers and fishermen over access to diminishing water resources. With the influx of arms to the Sahel region in recent decades, massacres have replaced traditional modes of dispute resolution; as one traditional chief in north Cameroon noted: “Today, when there is a problem between two people from different communities, all the communities get involved with weapons” (Reuters, December 9, 2021). Many Cameroonians have fled the violence into the CAR, while some 300,000 CAR residents have fled the other way into Cameroon.

The Russian Third Phase in Africa

Tsarist efforts to establish a colonial foothold in the Horn of Africa after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire in the late 19th century came to naught. This was despite the notable efforts of a handful of adventurous Russian officers and Cossacks who became influential in the court of the Abyssinian emperor and even managed to plant a Russian flag at Fashoda on the White Nile before the arrival of the French or British. However, there was little interest in Africa at St. Petersburg, as Russia focused on consolidating its rule in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Soviet efforts in the post-colonial era were more determined and resource-targeted, but decades of military and diplomatic work had unsatisfactory results – the Russians were expelled from Egypt due to Cold War political manoeuvring and the application of Marxist economics by inexperienced Soviet-trained leaders to non-industrial societies in sub-Saharan Africa resulted in famine, economic collapse and intractable civil wars. These latter, naturally, were fuelled by Western states desiring to make the communist presence in Africa as costly as possible. These strategies transformed Africa into a proxy battleground until the collapse of the Soviet Union ended the Soviet project in Africa.

Ten Russian BDRM-2 armored scout cars were delivered to FACA in 2020; two broke down almost immediately.

Ten Russian BDRM-2 armored scout cars were delivered to FACA in 2020; two broke down almost immediately.

The third phase of Russian interest in Africa may be inspired by Soviet-era efforts (especially its search for African military bases), but has abandoned the ideological element of the Soviets. This eases the entry of Russian business interests and resource extractors that are often closely tied to the provision of some combination of military contractors, arms supplies, personal security, political advisors and information manipulators. These, in turn, have direct connections to Kremlin insiders like Yevgeny Prigozhin (owner of the Wagner Group) who can get things done even without having official status in the Russian government. For unstable regimes with no other means of re-asserting government control in profitable but rebellious regions, it is an attractive model.

The Wagner Group and Russian arms arrived in January 2018, not long after a visit by President Touadéra to Sochi, where he met with Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov. Four years later, Russians have become a highly influential, if not dominant, force in the national army, the gendarmerie, the mineral sector, the presidency and the National Assembly. The Wagner force is mainly Russian, but is reported to include a number of Syrians and Libyans whose knowledge of Arabic is useful in dealing with the CAR’s Muslim communities.

A report leaked from the EU’s foreign service in November 2021 described Russia’s use of a “complex hybrid strategy” in the CAR, including “support through proxies in the National Assembly.” The report also noted the Wagner Group’s “alleged reliance” on official Russian military infrastructure, transport and health services (EU Observer, November 29, 2021). Two weeks later, the EU imposed sanctions on the Wagner Group and eight specific individuals associated with it, citing “serious human rights abuses, including torture, extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and killings [and] destabilising activities in some of the countries they operate in,” including Libya, Syria, Ukraine and the CAR.

In March 2021, the UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries cited various abuses by Russian mercenaries in the CAR, including mass summary executions, torture, arbitrary detentions, indiscriminate targeting of civilians and attacks on humanitarian workers. The UN investigators were also alarmed by the “proximity and interoperability” between the mercenaries and the peacekeepers of the UN’s Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en Centrafrique (MINUSCA) forces (Al-Jazeera, March 31, 2021). In response to the UN’s claim Russian fighters had looted and murdered in the CAR, Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov insisted such reports were “yet another lie” (AP, June 28, 2021). Anti-MINUSCA protests in Bangui organized by Touadéra’s Russian advisors quickly followed the release of the UN report. Since the protests, Russian diplomatic efforts have prevented UN experts from pursuing further investigations.

However, the relationship between MINUSCA and the Russians inevitably deteriorated as the year progressed due to the conflict between their mandates and the difference in their methods. Whatever cooperation existed between the two groups was finally put to rest on November 1, 2021, when ten unarmed Egyptian policemen joining the MINUSCA force were wounded at Bangui’s M’Poko Airport in an attack by the Russian-controlled Presidential Guard. MINUSCA described the attack as “deliberate and unjustifiable,” though a presidential spokesman claimed the reports had “nothing to do with reality” (Reuters, November 3, 2021; UN News, November 2, 2021). [2]

In recent weeks, Russian mercenaries in Bria, capital of the Haute Kotto prefecture, have been in the habit of rounding up young men on a daily basis for use as forced labor in the construction of a nearby base. When no young men were to be found for several days, the Russians carried out a military operation in the early morning, surrounding Bria and opening fire on fleeing youth. Four were killed, prompting the rest of the town to flee to the bush or to the safety of a nearby displaced persons’ camp. The Russians returned late in the day to carry away the bodies of the deceased from a mosque where they were awaiting burial (Journal de Bangui, January 5, 2020; HumAngle [Abuja], January 5, 2022).

Claims of abuses by Russians in the CAR have been dismissed by a Russian Foreign Ministry spokesman: “If the insinuations about their atrocities had any real foundation, and the local population was actively protesting, the CAR’s leadership would hardly have insisted on the further presence of specialists from Russia” (Financial Times, October 25, 2021).

The Russian fighters are steady consumers of imported vodka and land for a local vodka distillery in the CAR has already been expropriated. When vodka runs short, the mercenaries are known to add isopropyl alcohol, Mecurochrome and various chemical-based wound disinfectants to beer to give it the necessary kick. Three Russians died from drinking these concoctions in mid-2021; four more died and six others were hospitalized in the last week of January 2022. Troops of the Force Armée Centrafricaine (FACA – Armed Forces of Central Africa) are said to avoid drinking with their Russian comrades (Corbeaunews [Bangui], January 31, 2022).

Valery Zakharov is the CAR’s national security advisor, assuming both military and diplomatic roles, including negotiations with Mahamat Darassa and other rebel leaders. The former intelligence agent, variously described as a veteran of the FSB or the GRU, also has a business role through mining firm Lobaye Invest Sarlu and Séwa Sécurité (or Sewa Security Services – SSS), a Russian private military contractor (PMC) engaged to guard President Touadera and other CAR officials. [3] According to Zakharov, Russia is not presently seeking a military base in the CAR, but did not rule it out in the future: “There is already a Russian military representation in the CAR, which is still sufficient for operational coordination between the Central African and Russian Ministries of Defense, the issue of opening the base is not yet on the agenda” (Descifrando la Guerra, March 7, 2021). While a military base may become a reality in the future, for now instability in the CAR has created an entry point for Russian interests in the CAR’s valuable mining sector.

Russian Members of Sewa Security Services in the CAR (Jeune Afrique)

Russian Members of Sewa Security Services in the CAR (Jeune Afrique)

In a September 2021 interview, a defensive President Touadéra pretended to have little knowledge of Wagner, Sewa Security or Lobaye Invest, adding that an appeal for security assistance from EU states had failed to obtain a favorable response. However, Russia, “with whom we have a long-standing relationship,” responded positively with arms and military trainers: “I have nothing to hide about the Russians” (Africa Report, September 24, 2021).

Prigozhin is reported to control both M-Finans, specializing in precious metals and the provision of private security services, and Lobaye Invest Sarlu, specializing in the mining of non-ferrous metal ores. Mining permits are regularly issued without consultation of the CAR’s National Assembly, a violation of the national constitution (Jeune Afrique, August 20, 2019). According to the US Treasury Department, Prigozhin’s CAR operations are “reported to be coordinated with the Russian Federation’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Defense.” [4]

Yevgeny Khodotov is the managing director of Lobaye Invest Sarlu, with contracts to explore for gold and diamonds, sometimes through another company called M-Finance. The US Treasury Department has identified Khodotov as an associate of Prigozhin. He is reported to be in contact with Noureddine Adam, leader of a faction of the Runga-dominated Front Populaire pour la renaissance de la Centrafrique (FPRC), as well as former president Michel Djotodia (Jeune Afrique, August 20, 2019). [5] The FPRC, under its military commander Abdoulaye Hissène, is known for targeting Fulanis; in 2016 the group massacred 85 people in Bria during a brutal raid on the town that displaced 11,000 people (Reuters, November 26, 2016). The FPRC was targeted by government-controlled militias in 2019-20. Noureddine Adam is now believed to be living in Sudan after the CAR government’s counter-offensive.

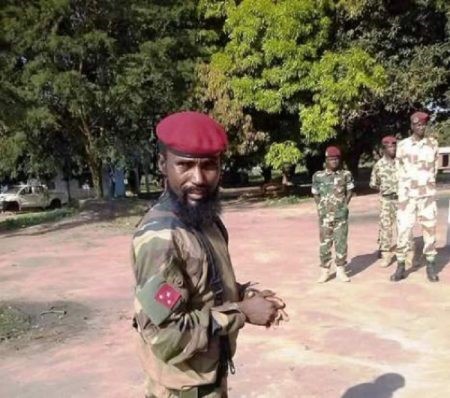

UPC Rebels, 2018 (Radio Ndeke Luka)

UPC Rebels, 2018 (Radio Ndeke Luka)

Reports of a massacre of civilians carried out in January near Bria (Haute-Kotto prefecture) by FACA and Russian mercenaries have ignited a UN investigation by MINUSCA officials. The incident occurred during a January 16-17 operation against Darassa’s UPC. Dozens of civilians were reported killed; a military source described “summary executions” and “more than 50 deaths” (AFP, January 21, 2022, al-Jazeera, January 22, 2022).

Nonetheless, Touadéra’s Russian advisors have tried to popularize the unfamiliar Russian presence in the CAR, providing medical services and sports equipment, funding a “Miss Centrafrique” contest and producing a film lionizing the Russian fighters. “The Tourist,” a Prigozhin-financed movie about young Russian military advisors in the CAR battling bloodthirsty rebels, was shown at a Bangui sports stadium to as many as 70,000 people, some of whom were helpfully supplied with Russian flags to show their enthusiasm. Dubbed into the local Sangho language (a lingua franca in the CAR), the movie featured Wagner Group mercenaries as extras. A “quickie” by film standards, the movie was shot in March-April 2021 and premiered in May (Moscow Times, May 21, 2021).

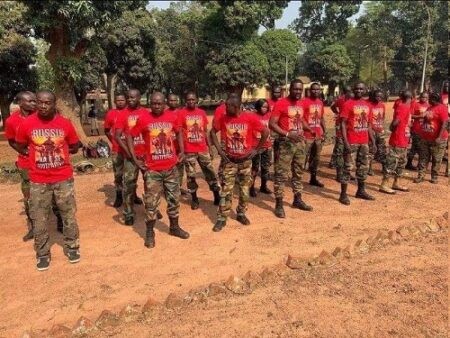

FACA Troops Wearing “Russie – Je Suis Wagner” T-shirts (Corbeaunews)

FACA Troops Wearing “Russie – Je Suis Wagner” T-shirts (Corbeaunews)

Displaying little regard for the political sensitivities of the CAR rulers who were trying to disavow any knowledge of Wagner Group mercenaries in the country, the Russian mercenaries created a “Je Suis Wagner” (I am Wagner) t-shirt they issued to the gendarmerie and FACA members (some of these bear a large “Russie” logo over the shirt’s image). Soon, the shirts were being worn by fashionable youth and members of the ruling party alike (Corbeaunews [Bangui], October 31, 2021).

Young Girl Styles “Je suis Wagner” T-shirt (Corbeau News)

Young Girl Styles “Je suis Wagner” T-shirt (Corbeau News)

The services of private Russian security firms don’t come cheap, and questions have been asked regarding the possibility that donations from the World Bank and the EU, which provide half of the CAR’s $400 million budget, might be used to pay the Russian mercenaries on top of access to gold and diamond deposits (Financial Times, October 25, 2021).

The French Reaction

Unhappy with the Russian challenge to France’s traditional zone of influence, French president Emmanuel Macron has used strong language to condemn the growing criticisms of France in the CAR: “This anti-French rhetoric legitimises the presence of predatory Russian mercenaries at the highest levels of the state, with President Touadéra who is today a hostage of the Wagner group. This group is taking over the mines and, in the same way, the political system” (Journal du Dimanche, May 29, 2021; RFI, May 31, 2021).

France is still far from out of the picture in the CAR, and some indication of its lingering influence might be seen in the June 10, 2021 resignation of Prime Minister Firmin Ngrebada and his cabinet. Ngrebada was an architect of the 2019 Khartoum Accord and believed to be close to the Russians, at whose embassy he sought refuge when the Séléka movement occupied Bangui in 2013. Five days after his resignation, he was replaced by former finance minister Henri Marie Dondra, believed to be closer to the French who lobbied hard for Ngrebada’s removal. Dondra, whose family lives in France, declined the protection of Russian bodyguards (Jeune Afrique, June 18, 2021). Despite Dondra’s acceptability to the IMF/World Bank, there has been internal pressure to replace him. Dondra is reported to have already submitted his resignation earlier this month; the president is expected to respond in the coming days. The prime minister has struggled with demands from the Wagner Group, a staff picked by a president to whom he has never been close, increased reluctance to provide continuing financial support to the CAR by France and the EU, and finally ethnic insults made by the spokesman of the leader of the National Assembly (African Intelligence, February 4, 2022). Though the World Bank is unhappy about the Russian mission’s influence on certain government institutions, Dondra’s successor is likely to be more accommodating to the Russian presence in the CAR.

The Investigation

To the surprise of many, on October 1, 2021 CAR Minister of Justice Arnaud Djoubaye Abazène (a relative of Michel Djotodia) released the results of an investigation by a Special Commission of Inquiry into human rights violations in the CAR that implicated the CPC rebels, MINUSCA troops and “Russian instructors who operate in support of FACA” in repeated and egregious violations (Le Monde/AFP, October 1, 2021). Aware of the repercussions the report would have, Djoubaye did not provide advance notice to the Russian military mission or the Russian embassy. After presenting the report, the Minister of Justice was roundly assailed as “pro-French” by deputies in the Touadera camp.

Only two weeks after Djoubaye made the accusations of war crimes and human rights violations public, the CAR’s National Assembly issued a public letter of thanks for the “interventions of the Russian contingent alongside our forces” in retaking the regions occupied by “terrorists,” along with “our sincere congratulations for your bravery” (Afrik.com, October 16, 2021). The letter, completely undermining the Minister of Justice, was yet another example of the growing Russian influence in the Assembly.

Djoubaye was forced to defend his report in a parliamentary interpellation several days later, though he opened by criticizing the “almost generalized impunity” enjoyed by military, political and criminal human rights violators in the CAR. Repeating that the majority of such violations were committed by rebel movements, Djoubaye noted the “privilege of jurisdiction” enjoyed by FACA’s foreign allies, an acknowledgement that crimes committed by these entities were unlikely to be prosecuted in the CAR. Attempting to still the waters, the Justice Minister finished by stating that the report of the Special Commission of Inquiry “was not intended to affect the morale of FACA or that of the allies who are applauded by our people” (Centrafrique-presse, October 24, 2021).

Djoubaye and the Tribal War in the North

Djoubaye has himself been accused of helping orchestrate attacks amounting to war crimes in his hometown of Birao (capital of Vakaga prefecture) in 2019. The attacks were carried out by pro-government militias on members of the Runga community, especially those close to the FPRC (Monde Afrique, July 3, 2021). Dozens were killed and tens of thousands displaced in the violence between neighboring ethnic groups.

The three militias involved in the attacks on the Runga included:

- The Mouvement des libérateurs centrafricains pour la justice (MLCJ), composed largely of Kara and Gula from the region of Birao. The MLCJ was founded by Abakar Sabone and is now led by Gilbert Toumou Deya, currently a cabinet minister under the integration terms of the Khartoum Accord. The political/military movement is reported to have been reinforced by Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries (Mondafrique, March 28, 2020).

- The Rassemblement patriotique pour le renouveau de la Centrafrique (RPRC). The movement’s founder and political leader, Herbert Gontran Djono Ahaba, is now a cabinet minister. The RPRC, operating in the northeast CAR, is now led in the field by Gula “General” Zakaria Damane (a.k.a. Moustapha Maloum). Damane cooperates with Lobaye Invest in the Ouadda region of Haute-Kotto prefecture.

- The Parti pour le rassemblement de la nation centrafricaine (PRNC) is led by Nour Gregaza (a.k.a. Mahamat Nour Nizan) and Issa Issaka Aubin, former army chief-of-staff under the presidency of Michel Djotodia (Mondafrique, March 28, 2020; RFI, June 6, 2019). The movement was created by a June 2019 split with the RPRC.

The clashes in Birao led to a vicious split in the ranks of the FPRC in neighboring Haute-Kotto prefecture. Diamonds appeared to be at the core of a further clash in Bria in January 2020, between the Kara and Gula peoples who own the mines and their former Runga allies in the FPRC who control the sale and trade of diamonds from the region (AFP, January 20, 2020). The fighting was joined by fighters of the Kara and Gula-dominated MLCJ. The FPRC’s internal ethnic struggle spread to its main base in Ndélé in the Bamingui-Bangoran prefecture (southwest of Vakaga prefecture) in April 2020, with dozens slaughtered. “General” Azor Kalité, a Bria-based Gula warlord and former senior member of the FPRC, and eight companions were arrested by MINUCA on suspicion of war crimes as the fighting continued in May (AFP, May 20, 2020; Monde Afrique, May 27, 2020). A pact of non-aggression between the Runga and Gula factions of the FPRC helped reduce the violence in August 2020. Ndélé was eventually recaptured by government forces in June 2021.

The Haute-Kotto and Vakaga prefectures are located on the historically turbulent fault line between Muslim north Africa and traditionally animist sub-Saharan Africa (which now includes many Christians). Many of the ethnic-groups of these regions converted to Islam in the 19th century as a way of attempting to evade enslavement by the Fulani, Arabs and Maba from Chad and Fur and Arabs from the Darfur sultanate (Muslims are forbidden to enslave other Muslims, though this restriction was not always observed in practice in Chad’s southern hinterland). Vakaga is the CAR’s northernmost prefecture and the only one to share borders with both Chad and Sudan. Though oil reserves are present in the region, it remains sparsely populated due to its depopulation by 19th century slave raids. Vakaga has been brought under some semblance of government control since the FACA/Russian/Rwandan offensive and many Hausa and Sara who fled to Sudan and Chad are considering a return (Corbeaunews [Bangui], January 31, 2022).

The Army of the Central African Republic

Senior FACA officers complain the Russians are recruiting their own battalions and deploying them to act as support units in their operations without respect to the FACA hierarchy (Corbeaunews [Bangui], December 21, 2021). To the chagrin of members of the European Union Training Mission (EUTM), many of their graduates, so carefully instructed in human rights issues, are heading straight into FACA battalions controlled by Russian mercenaries. The EUTM now focuses on strategic advice having suspended its training program two months ago over concerns it could not cooperate with Russian mercenaries that did not share the values of contributing European nations. An offer was made to resume training if Russian control of FACA ended and the army began to respect human rights, but these conditions seem unlikely to be met (Defense-gouv.fr, February 5, 2022).

A FACA soldier wearing the Wagner Group Death’s-Head patch (Corbeau News).

A FACA soldier wearing the Wagner Group Death’s-Head patch (Corbeau News).

Of even greater concern is last year’s wave of arrests of former and active FACA senior officers by Russian contractors with the apparent acquiescence of the government:

- Former FACA chief-of-staff General Ludovic Ngaïfei Lamademon was arrested at his home on January 16, 2021 and detained at the Camp Roux military prison, where he was questioned regarding his relationship with rebel CPC leaders. The arrest occurred when a column of FACA armored vehicles and Russian APCs smashed through the gates of his house, with FACA troops firing wildly despite the absence of any resistance. Ngaïfei was accused of organizing a coup against the government after speaking critically of the president in the local press. The retired general had been dismissed by President Touadéra following a dispute in 2018 (Corbeaunews [Bangui], February 1, 2021);

- Colonel Rodongo, commander of FACA’s signals battalion, was arrested by the Russians in Kaga-Bandaro;

- The Russians came for the captain-chief of the FACA detachment in Bria in July 2021. The officer fled to a local MINUSCA detachment, but was turned over to the interrogators of the research and investigation section of the CAR gendarmerie (Corbeaunews [Bangui], October 24, 2021).

- Colonel Moussa Kitoko, commander of the north-east military zone, was arrested at Ndélé by Russian mercenaries, who accused the colonel of selling ammunition to the FPRC rebel movement (Corbeaunews [Bangui], October 24, 2021).

- Chief Warrant Officer Guetel, head of the Berberati remand center, was also arrested by the Russians in mid-October, 2021.

Beside the arrests of their colleagues, FACA officers are, like their Chadian counterparts, unhappy with the system of promotion, which seems to elevate favorites of Touadéra or his Russian advisors. Despite the apparent success of the FACA/Russian/Rwandan offensive in early 2021, morale remains low in the army and defections to rebel groups are common. In August 2021, a group of soldiers of all ranks sent a 20-page letter to President Touadéra criticizing the handling of the army. The letter cited tribalism and favoritism in promotions, an unclear purpose for the army, the arrests of senior officers and the “humiliation and dishonor” in the ranks due to their subordination to the Wagner Company and Rwandan special forces: “Is it an army at the service of the people or an army to defend the interests of certain individuals who are in power?” (Journal de Bangui, August 23, 2021).

Female soldiers of FACA are no longer allowed on active operations due to the strong risk of sexual assault by their Russian allies under the influence of drugs and alcohol, something allegedly experienced by two out of three female recruits (Corbeaunews [Bangui], December 27, 2021; Letsunami.net [Bangui], January 15, 2022).

Major General and Chief of Staff of the Central African Armed Forces Zéphirin Mamadou is reported to work closely with General Oleg Polguyev, former intelligence chief of Russia’s airborne forces and a member of the official Russian mission (rather than Wagner).

Rwanda in the CAR

Rwanda is not a neighbor of the CAR, but, as with its earlier intervention in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the government of President Paul Kagame is interested in gaining access to mineral resources of the type found in the CAR.

The Rwandan component of MINUSCA consists of two infantry battalions, a mechanized battle group and a field hospital. Rwandans began providing protection for President Touadéra and other authorities in 2016 (East African (Nairobi), August 4, 2021). Rwanda is the largest single contributor to MINUSCA, with roughly 1700 troops and 500 policemen under UN command. [6]

In 2020, Rwanda deployed “force protection troops” from the Forces de Défense du Rwanda (FDR) to the CAR under a bilateral defense agreement. The agreement allowing Rwanda to deploy troops in the CAR outside the MINUSCA framework was signed in October 2019. Accompanying economic agreements gave Rwanda access to the CAR’s mining sector and permitted Rwandan officials to be inserted into CAR mining operations. The deployment came “in response to the targeting of the Rwanda Defense Force under the UN peacekeeping force by rebels supported by François Bozize” (Govt. of Rwanda, December 20, 2020). In early August 2021, another battalion of 750 troops from the FDR arrived in the CAR; one of their main tasks was to secure the vital highway connecting Bangui and Cameroon (New Times [Kigali], August 9, 2021).

According to Valery Zakharov, the Rwandans “act very efficiently and professionally. Of course, without the support of Rwanda, it would be difficult to repel the aggression of the militants and immediately go on the offensive. We are in constant contact with the Rwandan forces, as well as with all other partners” (Descifrando la Guerra, March 7, 2021).

Soldiers of Fortune in the CAR

Some European mercenaries have taken advantage of the CAR’s state of insecurity for their own profit. Horațiu Potra, a Romanian mercenary and former French Legionnaire, became involved in Baba Laddé’s plan to overthrow both François Bozizé and Idriss Déby. Potra, allegedly a dealer in war-zone diamonds, is closely associated with a number of rebels and mercenaries active in Chad and the CAR and was an instructor of the presidential guard of Ange-Félix Patassé.

Another shadowy adventurer is the Italian Elio Ciolini (a.k.a. Bruno Lugon, a.k.a. Bruno Raul Rivera Sanchez, a.k.a. Gino Bottoni Di Ferrara, a.k.a. Colonel Eliot). Nicknamed il faccendiere (“the henchman”), Ciolini has spent time in the prisons of several states on drug and weapons charges. Now working in the CAR as an “adviser to the presidency for national security,” Ciolini manufactured a fake coup attempt in Bangui while posing as “Colonel Eliot” of the European External Action Service (EEAS), the EU’s combined foreign and defence ministry. As “organizer” of the coup, Ciolini contacted a number of political and military leaders in the CAR in what seems to have been an attempt to flush out opponents of President Touadéra and his Russian backers. Ciolini was seen many times in Bangui in the company of Dmitri Alexandrov, a top Russian advisor to the president, before he disappeared in May 2020 (Jeune Afrique, July 1, 2020). Alexandrov (real name Dmitri Sergeevich Sytii) is a director of Lobaye Invest, a Russian mining firm tied to Prigozhin operating in the CAR. Sytii, who speaks four languages, works as an interpreter in high level talks and leads propaganda operations in Bangui that denounce MINUSCA and local politicians who resist the Russian expansion or favor a partnership with France.

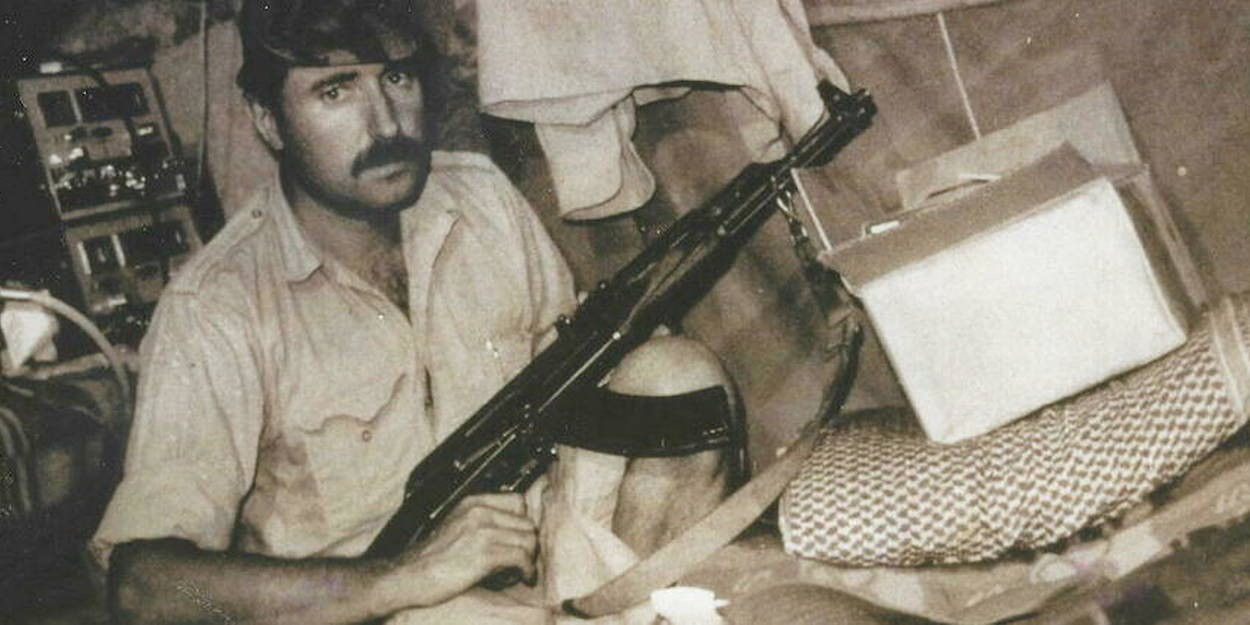

Two days after France suspended a military training and operational support mission to the CAR in June 2021 to protest the failure of Ngrebada’s government to combat an anti-French disinformation campaign on social media, French national Juan Rémy Quignolot was charged with weapons, espionage and threats to state security (i.e., aiding and training rebel groups). The charges came a month after the former French paratrooper, known to work as a bodyguard for aid organizations, was arrested in Bangui with a small cache of weapons, a few camouflage uniforms and cash in several currencies. Though the arms seized from Quignolot were described in many places as “a very large arsenal” endangering the state, photos of the seized weapons and gear revealed only two hunting rifles (one with a scope), a handgun and an M-16 automatic rifle, nothing especially unusual for a security practitioner in an insecure region and certainly not enough to mount a coup, as CAR security has suggested was his intent. [7] Paris quickly characterized the arrest as a “manipulation” and part of an anti-French disinformation campaign after reports of the seized “arsenal” and arrest were prominently featured on Valery Zakharov’s Twitter account (al-Jazeera, June 9, 2021). The 55-year-old’s arrest came at a time when accusations were being made of human rights abuses by the Wagner Group in the CAR. According to his sister, Quignolot is being held in solitary confinement with a daily plate of rice to keep him alive as he faces a possible sentence of life at hard labor (Corbeaunews [Bangui], January 9, 2022).

Conclusion

In the CAR, it has become clear a cabinet of government ministers cannot be formed from rebel leaders and bandit chiefs, especially those who serve only themselves and have committed war-crimes and murders of CAR civilians. The impunity enjoyed by those rebel leaders now absorbed into the highest levels of the government only encourages others to view violence as the quickest path to wealth and influence. Such a structure cannot hold, hence the need for no-questions-asked assistance from mercenaries.

Alexander Bikantov, a proponent of a Russian presence in the CAR, is taking over as Russian ambassador this month from Vladimir Titorenko, who was perceived locally as inserting himself into CAR politics and was also occasionally at odds with Wagner Group officials. In October/November 2021, Bangui was visited by both Yevgeny Prigozhin and Wagner Group founder Dmitri Utkin in an attempt to calm growing differences between the Russians and CAR authorities.

Weak states compelled to hire mercenary forces to enable their survival are always at risk of the mercenaries taking over state institutions for their own profit, especially if expected wealth does not materialize. From the mutiny of mercenaries over pay in 3rd Century BCE Carthage to the mercenary mutinies in 1960s Congo, it is a familiar pattern. If continued insecurity in mineral-rich areas and pushback from CAR politicians delays the get-rich-quick schemes of the Russian mercenaries and their backers, the result could be an internal conflict that would both test and reveal Moscow’s control over the military contractors.

The Russians are strong enough to take rebel-held towns and territory, but lack sufficient numbers to occupy them, a task that is turned over to the unreliable forces of FACA. Rebel movements are, in classic guerrilla fashion, able to melt into the bush to await the departure of the Russians and Rwandans before moving back into their usual areas of operation. The incompetence of the national security forces prevents the delivery of state services and humanitarian relief to areas in desperate need of same, encouraging further rounds of rebellion. The victories obtained by the Russians are thus illusory; as elation over the initial success of the 2021 anti-rebel offensive dissipates and the mission becomes overwhelmed by the very real (but unprofitable) needs of the population, the Russian contractors will be more likely to focus on protecting the mining facilities operated by Russian interests.

The mandate for the EUTM to provide ethical and military training to FACA will expire in September 2022 and cannot be renewed without the approval of President Touadéra and his government. At the moment, training has been suspended, and if the mandate is not renewed (and it is questionable whether the EU at this point even has any interest itself in renewing it), it is likely that military training will fall to the Russians, completing their takeover of FACA.

Mercenaries are ultimately a poor means for states to project power and influence; without the discipline of formal military structures, they begin to act with an assumed license that is ultimately counterproductive to the interests of state sponsors. Such was the experience of the Americans with the Blackwater PMC in Iraq; even Bob Denard, with all his contacts in the French secret services, was eventually reined in and arrested by French troops in the Comoros Islands in 1995 after mounting his fourth coup attempt.

Managing the ever-shifting ethnic rivalries and alliances in rebellious and difficult-to-reach parts of the CAR will tax the patience of the small Russian force of advisors and mercenaries, intensifying a greater focus on profits rather than security. The Russian role in driving the rebel formations back into the bush has helped build Russian popularity in some sectors of society, but this may quickly evaporate if the contractors come to be seen as economic predators.

Notes

- For the SADF experience in Bangui, see: “South African Military Disaster in the Central African Republic: Part One – The Rebel Offensive,” April 4, 2013, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=238, and “South African Military Disaster in the Central African Republic: Part Two – The Political and Strategic Fallout,” April 4, 2013, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=236. For Eeben Barlow and mercenary tactics used against Boko Haram in Nigeria, see: “Last Hurrah or Sign of the Future? The Performance of South African Mercenaries against Boko Haram,” AIS Tips and Trends: The African Security Report, June 30, 2015, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3371.

- Egypt contributes over 1,000 troops to MINUSCA, making it the fourth largest contributor.

- Federal’naya sluzhba bezopasnosti (FSB – Federal Security Service) is Russia’s domestic intelligence agency. The Glavnoje Razvedyvatel’noje Upravlenije (GRU – Main Intelligence Directorate) is the main military intelligence agency.

- “Treasury Increases Pressure on Russian Financier,” US Department of the Treasury Press Release, September 23, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1133

- In 2015, Noureddine Adam tried unsuccessfully to resurrect an expanded version of the old Dar al-Kuti sultanate called “the Republic of Logone.” In its early days (1830-1890) the sultanate was under the control of the Chadian sultanate of Wadai, providing the Wadaians with a steady source of slaves and ivory; in its latter years (1890-1911), the sultanate was invaded by the Nubian slaver Rabih al-Zubayr (1842-1900), who used it as a base for even more intensive slave raids in the region. The Islamic sultanate and its slave-labor plantations survived Rabih’s death at the hands of the French for some years under Rabih’s successor, Muhammad al-Sanusi.

- The top ten military contributors to MINUSCA include seven African nations and three Asian nations. MINUSCA Fact Sheet, January 5, 2022, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minusca

- Private ownership of a semi-automatic rifle is illegal in the CAR.