Andrew McGregor

Military History Quarterly 17(1), Autumn 2004, pp. 52-61.

Trading the sands of North Africa for the jungles of Tonkin, French Foreign Legionnaires and Vietnamese riflemen fought off waves of Chinese attackers for thirty-six days in 1885 at remote Tuyen Quang.

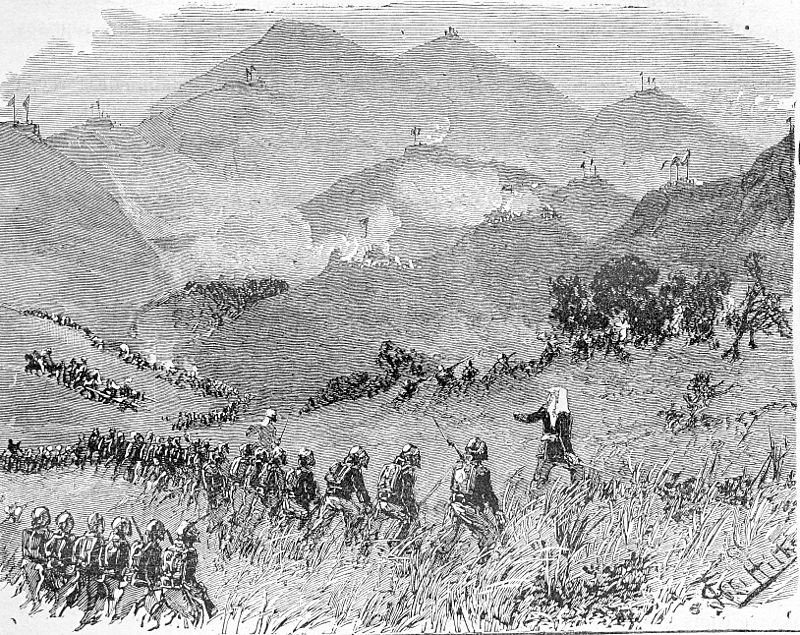

Siège de Tuyên Quang (1884-1885), by Hippolyte Charlemagne

Siège de Tuyên Quang (1884-1885), by Hippolyte Charlemagne

Tired and bloodied, a long relief column of French troops snaked its way through the thick Tonkinese jungle late on the afternoon of March 3, 1885. As the soldiers emerged into a large clearing surrounding a battered fortress, their senses were overcome by a gruesome spectacle. One officer recalled, “All the approaches – churned, blasted, lamentable – were covered with corpses and the carrion rotted in the air.” The column had reached its destination: Tuyen Quang, where a small garrison mainly composed of Foreign Legionnaires had been battling as many as twenty-four thousand Chinese attackers since January 26.

Commerce and religion had drawn France to Vietnam in the first half of the nineteenth century. The persecution of Christian missionaries there resulted in French military intervention in the form of several clashes on land and sea in the 1840s. France was also envious of recent British success in gaining access to lucrative Chinese markets, and hoped to open up Southeast Asia to French trade and gain access to China via northern Vietnam. The Vietnamese emperor, who ruled from Hué, was well aware of France’s colonial intentions. According to an 1848 imperial commission report:

These barbarians are very firm and patient; the works they have not been able to complete they hand on to their posterity to bring forth to completion. They relinquish no undertaking and are disturbed at no difficulties… These barbarians enter every land with neither fear nor weariness; they conquer all peoples, regardless of expense… They pretend to seek commercial freedom, but actually this is the means to spread their dark and monstrous errors. They are interested but little in commerce, but under its guise seek to render futile the laws of the empire… These men, akin to sheep and dogs by their manners, cannot be persuaded by the language of reason; reason to them is the voice of the cannon. In the art of making the cannon speak, they are extremely clever!

Continued persecution of Christians led to more clashes in the 1850s that culminated with the French capture (with Spanish assistance) of Tourane (present-day Da Nang) in 1858 and the occupation of Saigon in southern Vietnam the following year. Over the next few years the French expanded their hold over southern Vietnam. They referred to that region as Cochin China, to central Vietnam as Annam, and to the north as Tonkin. In 1862 the imperial court reluctantly ceded several provinces of Cochin China to France, which also gained a protectorate over Cambodia the next year, and during the next several years extended its control to include all of southern Vietnam.

China, however, had regarded Vietnam as part of the Celestial Empire for more than a thousand years. Initially the French were encouraged by the lack of Chinese protests to their advances in Cochin China and to an 1874 treaty between France and Vietnam that declared the remainder of the country “independent of all foreign powers” while giving France concessions in Tonkin’s Haiphong and Hanoi. It seems that the Chinese leadership failed to grasp that the French regarded the treaty as ending Vietnam’s tributary relationship with its northern neighbor. The French interpretation was apparently also misunderstood by the imperial court in Hué, which continued its former relationship with China.

China, however, had regarded Vietnam as part of the Celestial Empire for more than a thousand years. Initially the French were encouraged by the lack of Chinese protests to their advances in Cochin China and to an 1874 treaty between France and Vietnam that declared the remainder of the country “independent of all foreign powers” while giving France concessions in Tonkin’s Haiphong and Hanoi. It seems that the Chinese leadership failed to grasp that the French regarded the treaty as ending Vietnam’s tributary relationship with its northern neighbor. The French interpretation was apparently also misunderstood by the imperial court in Hué, which continued its former relationship with China.

Black Flag leader Liu Yung-fu

Black Flag leader Liu Yung-fu

During this period, Tonkin was wracked by fighting that at one time or another pitted Chinese, Vietnamese and Montagnards (the indigenous people of Vietnam’s Central Highlands) against each other. An army of Chinese brigands known as the Black Flags emerged as the most ruthless and successful of the combatants. The fighters were led by Liu Yung-fu, who, although illiterate, was widely regarded as a formidable strategist. He had turned bandit in southeastern China’s Guangxi Province during the chaotic days of the Taiping rebellion in the 1850s, and before long Liu had thousands of followers who swore allegiance to him before a black flag.

After crossing the Vietnamese border with his followers, Liu ingratiated himself with the local authorities by defeating the defiant Montagnard tribesmen of north Tonkin. The Black Flags, with the blessing of Chinese and Vietnamese officials, then began a long campaign against a rival brigand band, the Yellow Flags. In 1875, after more than five years of fighting, the Black Flags emerged victorious. Liu’s forces were now the foremost military power in Tonkin.

Over the next several years, France became increasingly concerned about the security of its concessions in Hanoi and Haiphong and frustrated by its inability to make further inroads in opening Tonkin’s Red River to trade. Then in 1882 French naval Captain Henri Laurent Rivière arrived in Hanoi at the head of several hundred troops sent as reinforcements for the concession there. Disobeying his explicit orders, he stormed and captured the city’s citadel on April 25.

Rivière, having seized northern Vietnam’s seat of government, soon found himself unable to expand his hold in Tonkin and was virtually cut off in Hanoi. Vietnamese authorities turned to the Black Flags, and a steady stream of their troops, as well as other Chinese fighters, poured into the countryside around Hanoi. Liu expressed his opinion of the French occupiers in an invective-filled ultimatum:

You French brigands live by violence in Europe and glare out on all the world like tigers, seeking for a place to exercise your craft and cruelty. Where there is land you lick your chops for lust of it; where there are riches you would fain lay hands on them. You send out teachers of religion to undermine and ruin the people. You say you wish for international commerce, but you merely wish to swallow up the country. There are no bounds to your cruelty, and there is no name for your wickedness. You trust in your strength, and you debauch our women and our youth. Surely this excites the indignation of gods and men, and is past the endurance of heaven and earth… If you own that you are no match for us; if you acknowledge that you carrion Jews are only fit to grease the edge of our blades; if you would still remain alive, then behead your leaders, bring their heads to my official abode, leave our city, and return to your foul lairs.

Rivière’s forces had been besieged in Hanoi for about eleven months when the ambitious captain was killed in May 1883 during an operation to loosen the Chinese grip around the city. France promptly used his death to step up its efforts to subdue all of Vietnam. In August, French warships bombarded Hué and landed troops nearby. The emperor immediately called for a cease-fire and reluctantly signed a treaty allowing France to establish protectorates over Tonkin and Annam. The Chinese, however, explicitly rejected the treaty’s terms.

Algerian “Turcos” and fusiliers-marins (armed sailors) at Bắc Ninh, 1884.

Algerian “Turcos” and fusiliers-marins (armed sailors) at Bắc Ninh, 1884.

As part of France’s redoubled efforts, the Foreign Legion’s 1st Battalion arrived at Haiphong Harbor in November 1883 intent on suppressing the Black Flags and expelling the Chinese from Tonkin. The unit did not have to wait long to see action, successfully storming the well-defended Black Flag stronghold at Son Tay on December 16, 1883. After being reinforced by the 2nd Battalion in February 1884, the legionnaires occupied the former Chinese fort at Bac Ninh in March. Two months later, China agreed to withdraw its forces from northern Vietnam and it appeared that the French conquest of Tonkin was complete.

That impression, however, was shattered when a French column en route to occupy Lang Son (in northern Tonkin) attacked but was repulsed by a Chinese garrison that had remained behind. To punish China, France embarked on an ambitious two-front war. One French force was to invade the Chinese island of Formosa, while a second was to reinforce troops already in Tonkin that would then pacify the Red River Delta and extend French control farther inland.

Like many colonial conflicts of the time, the ensuing war was presented to the French public as a series of flag-plantings, bugle calls and triumphant bayonet charges. The reality, of course, was much harsher. In fact, France never officially declared war against China; according to international law, doing so would have prevented French ships from refueling at the neutral ports of Ceylon, Singapore, and Hong Kong and thus would have completely disrupted supply lines. The Chinese likewise did not declare war, as they were awaiting military supplies ordered in Europe, and a declaration of war would have resulted in the contracts’ suspension.

The conflict in Tonkin was an especially brutal one from the beginning and was played out in unforgiving jungle and heavily wooded limestone mountains. It was a war without quarter. Chinese and Vietnamese prisoners were regularly executed, and French prisoners could expect to be decapitated, with their heads pickled in brine before being exhibited as trophies. The French were also known to display the severed heads of enemy combatants in an effort to weaken Chinese resistance. The two sides plundered and raped the helpless population, both in victory and in defeat.

Black Flag fighters

Black Flag fighters

The Tonkin war also fired up the prejudices of the participants as well as observers. The Chinese and native Vietnamese were particularly shocked by their introduction to French colonial troops, especially those from North Africa. According to the Black Flags’ Liu Yung-fu, “You [the French] set black devils to plunder and ravage a defenseless population, more cruelly than the vilest of bandits.” A British reporter alluded to the alleged rapacity of the North Africans: “The bestiality of the Turcos [Algerians] is not to be laid, perhaps, at the French door, except that if the French introduce such animals into a country they ought to muzzle them.” Answering charges of French brutality, French writer Pierre Loti noted: “After all, in the Far East, to destroy is the first law of war. And then, when one comes with but a handful of men to subjugate an immense country, the enterprise is so adventurous that one must spread much terror, under penalty of perishing one’s self.”

Initially France relied on Foreign Legionnaires and troops of the Ministère de la Marine (Naval Ministry) for the combat component of its expeditionary force in Vietnam. The Foreign Legion of the 1880s was largely composed of men from the former French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, which had been annexed by Germany after the Franco-Prussian War. Also, Germans were well represented, as were Belgians, though many of the latter were actually Frenchmen evading the prohibition on the enlistment of native French in the legion by pretending to be French-speaking Belgian Walloons. The geographic contrast was stark between the legion’s normal sunny and wind-swept posts of North Africa and the humid bush of Tonkin, where one could often not see through the thick jungle more than a few feet ahead. The soldiers of the Legion, however, proved remarkably adaptable – more so, in fact, than their officers, who persisted in sacrificing their men (and themselves) in European battlefield tactics.

Tirailleurs Tonkinois

Tirailleurs Tonkinois

Tropical uniforms were slow in arriving, and the typical French soldier on the march carried an absurd amount of equipment. By 1883 France had begun recruiting militia in Cochin China and Christian convert auxiliaries in Tonkin. Legionnaire Charles Martyn complained of the native north Vietnamese light infantry serving with the French, the Tirailleurs Tonkinois: “It is beneath the dignity of these warriors to carry anything beyond their arms and ammunition, so our column presented the strange spectacle of natives of the country loafing along at their ease while we Europeans were loaded up like pedlars’ asses.”

“Loaded up like pedlars’ asses”: A Legionnaire on the march in Indo-China.

“Loaded up like pedlars’ asses”: A Legionnaire on the march in Indo-China.

Ironically, by 1883 the Black Flags were armed with modern repeating rifles of European and American make, including Remingtons, Spencers, Winchesters and Martini-Henrys, while France’s troops made do with outdated single-shot Model 1874 Gras rifles. Fortunately for the French, many of the Chinese and brigands seemed to entirely misunderstand the principle of their weapons, firing at an upward angle in order to “drop” bullets onto their enemy. There was a widespread opinion in the French camp that Chinese troops had a special distaste for the Gras’ fearsome twenty-one inch bayonet blade. The bayonet charge thus became a staple of Foreign Legion warfare in Indochina. Overconfidence in this tactic (often ordered without artillery support) would cost many legionnaires their lives during the following years.

The Chinese, despite their weaponry, must have presented an unmilitary appearance to the Europeans. According to a French officer: “Some had a black garment decorated in blue, others a black garment with red borders, others a garment in iron-gray, a certain number wore an all-red costume, others a sky-blue costume; finally a group wore a sort of dark-blue smock. These last are without doubt some Black Flags.” The Black Flags had also readopted the Manchu pigtails (abandoned in China during the Taiping rebellion) and typically wore the broad conical straw hat of southern China and Vietnam.

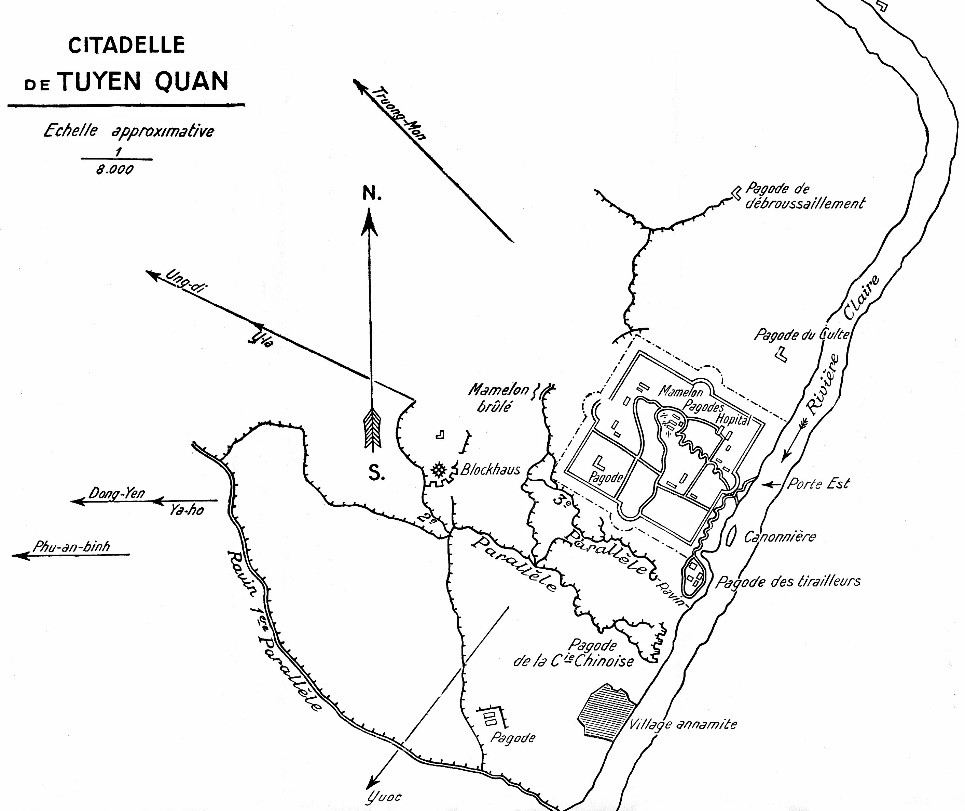

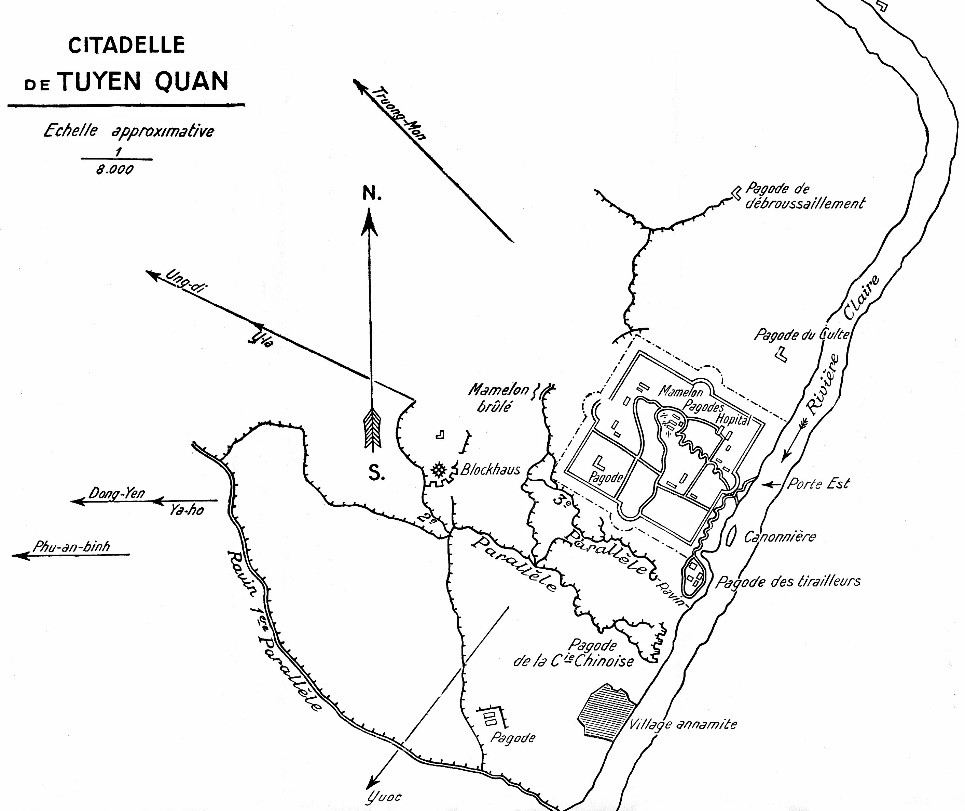

In May 1884 French forces, extending control toward Tonkin’s highlands, occupied a Chinese-built square fort at Tuyen Quang, on the west bank of the Clear River, a tributary of the Red River. The area’s generally low-lying ground was accented by many rounded, steep-sided hillocks that the French called mamelons (nipples). One of these distinctive hills, seventy meters in height, was enclosed within the four three-hundred meter long by three-meter high walls of the fortress and provided an excellent observation point. The areas was also full of multi-storied pagodas, several of which lay within the brick walls of the citadel. A group of small pagodas surmounted the fort’s mamelon and served as quarters for the French officers. A small village of about one hundred Vietnamese peasants was located four hundred meters downstream from the citadel.

Disease soon started taking a toll on the small garrison, and in October French patrols began clashing with bands of Black Flags. Before long, thousands of the brigands were deploying in the jungles surrounding Tuyen Quang. The next month, the garrison was reinforced by the arrival of the 1st and 2nd companies of the Legion’s 1st Foreign Regiment, along with a company of freshly raised Tirailleurs Tonkinois, gunners of the Artillerie de la Marine to man a section of four small cannons, a detachment of eight sappers from the 4th Engineers, and the dozen sailors from the small gunboat Mitrailleuse, which was anchored off the citadel. Altogether, the garrison then numbered 619 men, 390 of whom were Foreign Legionnaires. Ammunition supplies were meager, but six month’s-worth of foodstuffs were on hand.

The legionnaires initially viewed the Tirailleurs with skepticism, and the latter were settled in a small pagoda-centered camp abutting the south corner of the fort. One member of the garrison recalled: “They had no drill to speak of, and they were dressed in a most hideous streaky blue uniform, with a singular ugly red, white and blue-tipped bamboo, soup-tureen like hat. The number of their company, sewed in red tape on a white oval on the left chest, dealt the final blow at any hopes they might have had of presenting a soldier-like appearance.” Moreover, several companies of the Tirailleurs had deserted earlier in 1884, taking their weapons and ammunition with them. Though the French troops initially deprecated them, referring to the north Vietnamese soldiers as bashi-bazouks – a reference to the Turkish army’s undisciplined irregular troops – the Tirailleurs soon displayed the endurance, marching ability, aggressiveness and steadiness under fire that would later bedevil French and US armies in the twentieth century.

Marc-Edmond Dominé (1848–1920), the commander of the Tuyen Quang garrison.

Marc-Edmond Dominé (1848–1920), the commander of the Tuyen Quang garrison.

The garrison’s commander, thirty-seven year old Major Marc-Edmond Dominé, was a veteran officer of the hard-fighting Bataillions d’Afrique (known as the Bats d’Af), North African penal units in which conscripted and heavily tattooed ex-convicts could redeem themselves by performing the most hazardous battlefield tasks. Dominé quickly set his men to work building additional fortifications. A former journalist, twenty-five year old Sergeant Jule Bobillot of the 4th Engineers oversaw the construction of a bamboo palisade that surrounded the fort, as well as trenches, dugouts and earthworks in the strongpoint. A large mamelon three hundred meters west of the fort was judged a threat to the security of the citadel if occupied by the Black Flags, so Dominé ordered the talented Bobillot and his sappers to construct a fortified blockhouse on its summit. With the help of seventy legionnaires, the engineers completed the blockhouse in only six days.

For a time the garrison was able to stockpile supplies brought in on river junks escorted by French colonial troops. The last convoy arrived on December 20 and carried the all-important wine that French armies lived on at the time.

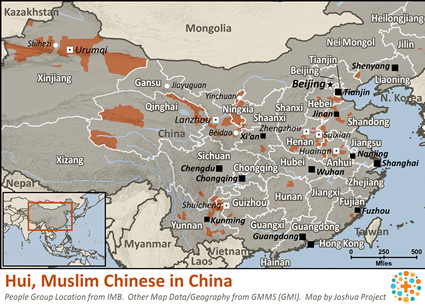

In January 1885 a twelve-thousand-man army of Chinese regulars from the southeastern province of Yunnan reinforced the thousands of Black Flag troops outside Tuyen Quang. The Yunnanese soldiers were expert in the construction of earthworks and field fortifications and in mine warfare, all learned by the province’s miners who had fought on both sides of the Muslim rebellion in their home province during the 1860s. These troops quickly set to work digging an intricate system of trenches that crept ever closer to the citadel, as well as building earthworks to defend against any force attempting to relieve Tuyen Quang.

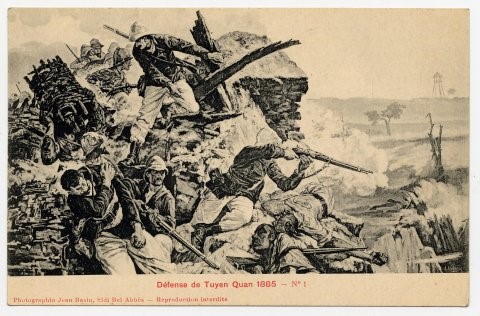

A fanciful depiction of the Siege of Tuyen Quang – The pristine Legionnaires wear North African dress uniforms rather than tropical kit. The Black Flags are similarly outfitted like wealthy mandarins. Loose-fitting black clothes comprised the most common Black Flag “uniform” and bayonets were not a normal part of their weaponry.

A fanciful depiction of the Siege of Tuyen Quang – The pristine Legionnaires wear North African dress uniforms rather than tropical kit. The Black Flags are similarly outfitted like wealthy mandarins. Loose-fitting black clothes comprised the most common Black Flag “uniform” and bayonets were not a normal part of their weaponry.

On January 26, Liu launched the first concerted attacks on the French positions. After torching the Vietnamese village, troops assaulted the blockhouse and the bamboo palisades erected outside the walls of the citadel. In a typical Blag Flag onslaught, the attackers rushed forward screaming, banging gongs and cymbals, blowing trumpets and waving numerous banners. Three columns of three hundred men each advanced on the blockhouse, which was defended by only eighteen soldiers under the command of Sergeant Libert of the Foreign Legion. Two of the columns were quickly driven off by shell fire from the Mitrailleuse and rifle fire from the blockhouse and the citadel, but the third group of attackers was more tenacious and only fell back after the French opened up with their small cannons.

The fierce fight and the hundreds of enemy campfires visible at night on the hills surrounding Tuyen Quang alerted the garrison to its desperate predicament. No mercy could be expected from the Chinese, so surrender was out of the question. Virtually cut off from the outside world, the garrison resorted to tossing messages stuffed in bottles or bamboo tubes into the Clear River in the hope that they might make it to their comrades downstream.

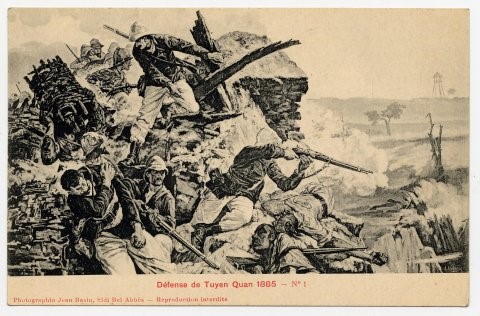

A more realistic view of the battle, from a contemporary French postcard.

A more realistic view of the battle, from a contemporary French postcard.

By the end of January, Dominé found it necessary to abandon the blockhouse after discovering the Chinese had tunnelled under it, where they were likely preparing to ignite a mine. A small French victory was earned when its garrison crossed the three hundred meters of no man’s land to the fort with the loss of only one soldier. Surrendering the mamelon was a severe blow as it allowed the Chinese to extend their entrenchments around the west corner of the citadel without having to worry about fire from their rear. The Black Flags were also able to deploy some outdated Krupp cannons on the mamelon which they had hauled through the jungle on the backs of elephants. The garrison was soon taking daily losses from a constant artillery bombardment.

While the Legionnaires and tirailleurs were battling for their lives at Tuyen Quang, French reinforcements had arrived in eastern Tonkin. The fresh troops allowed General Louis-Alexandre Brière de l’Isle, commander of France’s forces in the province, to launch a campaign to clear the northern route through Lang Son to the “Gates of China,” a narrow defile along the mountainous border. His column of about nine thousand soldiers set out on February 3.

Meanwhile, outside Tuyen Quang, the Yunnanese sappers devoted their labors to the citadel’s southwest wall, once protected by flanking fire from the blockhouse. Mines were run up right against the wall, but Bobillot’s small group of engineers dug counter-mines. At one point a group of French sappers unintentionally broke through into a Chinese tunnel, sparking a short firefight in the dark between the two surprised parties. By February 5, Chinese troops had crossed the river and from the east bank began a steady fire that made life uncomfortable in the tirailleurs’ camp and aboard the Mitrailleuse.

On the morning of February 5, the garrison beheld a peculiar sight when a Chinese soldier wearing a mask covered in charms and amulets came close to the citadel walls and planted a flag. The act was certainly a type of ritual designed to weaken the garrison; despite his strategic skills, Liu was prey to almost every form of superstition. A lieutenant and several of his men along the wall used a rope noose attached to a bamboo pole too snag the banner and were pulling it into the citadel when two Chinese soldiers attempted to save the flag, only to be shot dead.

At 5:45 AM on February 12, a thunderous explosion shook the early dawn as a one-hundred-kilogram mine placed by the Yunnanese against the base of the fortress exploded. Thousands of Black Flags poured out of their trenches and rushed toward the breach, but sheets of deadly rifle fire forced the attackers to withdraw. A simultaneous assault on the tirailleurs camp was also driven off.

Another mine explosion followed the next night, this time toppling a section of wall near the west corner of the citadel. Again thousands of Chinese rushed for the opening, and one even managed to plant his flag at the summit of the breach. The legionnaires and tirailleurs poured heavy rifle fire into the opening and dead and wounded attackers began falling into the mine’s crater, making it difficult for those behind to pass through the breach in the wall. The Foreign Legion counter-attacked, and for a time bitter hand-to-hand fighting raged for control of the gap before the Black Flags broke off their assaults. The garrison had repulsed another attack, but there was no time to rest, as new bamboo palisades needed to be built to fill the gaps in the citadel’s defenses.

On the night of February 15, the Chinese again assaulted the fort’s weakened west corner. Sergeant Beulin gathered twenty-five volunteers and drove off the Chinese with a furious bayonet charge in which four legionnaires were killed. Although the garrison managed to beat off successive attacks, the citadel was being demolished bit by bit. To bolster the crumbling fortifications, Dominé assigned forty Legion volunteers to form permanent, rotating work parties under the command of Sergeant Bobillot. On the eighteenth, however, the garrison suffered a critical loss when Bobillot was mortally wounded. In his journal entry for the day, Dominé also noted the loss of three large barrels of wine to shrapnel.

A statue of Sergeant Bobillot was erected in Paris but was melted down by German occupation forces in 1942.

A statue of Sergeant Bobillot was erected in Paris but was melted down by German occupation forces in 1942.

Liu soon resumed his tactic of blowing a breach in the fort’s walls and then launching waves of attackers in an attempt to storm through the opening. On the twenty-second, Captain Cattelin saved his men from destruction by moving them away from the wall they were defending when he heard the screams, gongs and trumpets that preceded a Chinese attack. The subsequent mine explosion breached the wall but resulted in few casualties.

Captain Jean-Baptiste Moulinay, commander of the 1st Company, then moved his legionnaires into the opening to repel the expected attack, but the Chinese had cunningly planted a second mine which detonated and killed Moulinay and a dozen of his men and wounded thirty others. The Chinese then launched their clamorous assault. Tuyen Quang’s defenders were nevertheless able to rally, and with rifle fire and the points of their bayonets turned back the attackers.

The legionnaires and tirailleurs earned only a brief respite. During an assault two days later, a group of Chinese battled their way into the fort and fought off two French counterattacks before Capatin Cattelin arrived with his reserves, driving off the enemy a la baïonnette. By month’s end, the French had only 180 working rifles, and Chinese mines and artillery had reduced more than 10 percent of the citadel’s walls to rubble. The last day of February saw some of the gravest fighting of the siege, with more mine explosions and massed Chinese attacks against the gaping breaches in the French position. But again and again the exhausted garrison was somehow able to muster the energy and firepower to repel the assaults.

During the siege Major Dominé had been trying to summon help for the beleaguered garrison. Vietnamese laborers carrying messages about the command’s desperate plight had been quietly slipping out of the fort and through the enemy’s lines. Against all odds, one of the messengers had returned to the fort on February 25 with news that a three-thousand man column led by General Brière de l’Isle was advancing to the garrison’s relief.

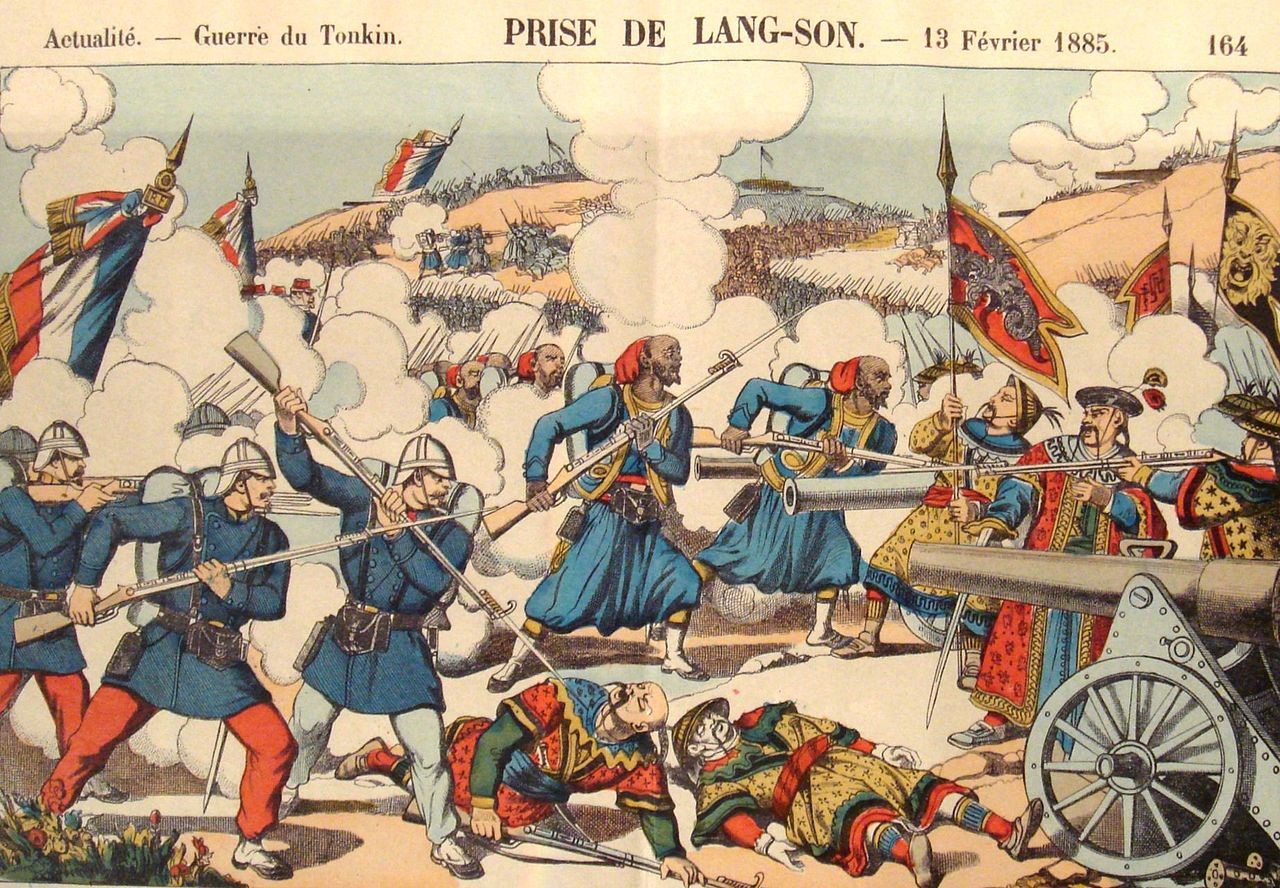

French Marines (colonial infantry) and Algerian tirailleurs (riflemen) take Lang Son. In reality, the decisive battle for Lang Son was fought at nearby Bac Vie in a heavy fog.

French Marines (colonial infantry) and Algerian tirailleurs (riflemen) take Lang Son. In reality, the decisive battle for Lang Son was fought at nearby Bac Vie in a heavy fog.

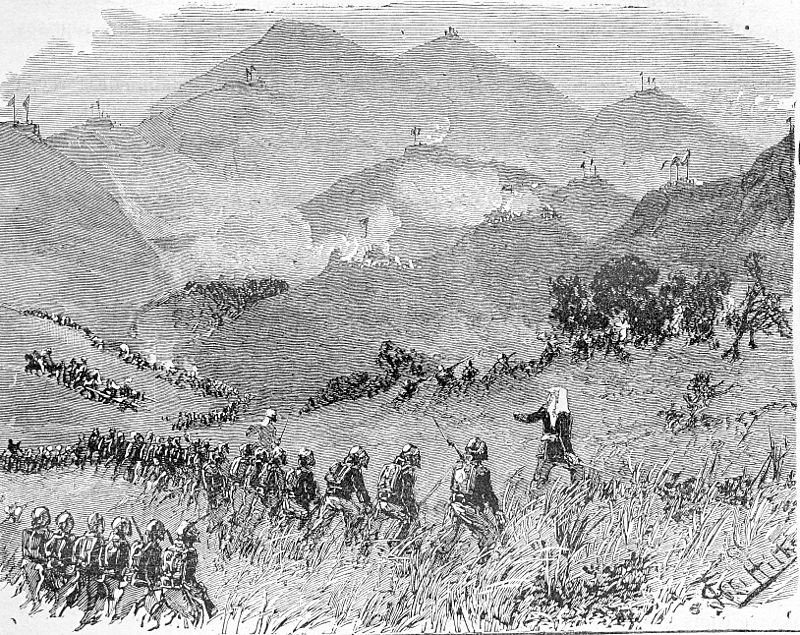

The French commander’s northern expedition had routed a Chinese army that had crossed into northern Vietnam from Guangxi province on February 13, and after entering Lang Son unopposed his troops pushed on to the Gates of China, where they blew up the stone entrance to the fortified defile. Brière de l’Isle then received word of the Tuyen Quang garrison’s plight. Leaving General François-Marie-Casimir de Négrier in charge of the bulk of his troops, de l’Isle hurried south at the head of the relief force.

A more realistic depiction of the battle at Bac Vie. The Algerians took heavy losses in the victory.

A more realistic depiction of the battle at Bac Vie. The Algerians took heavy losses in the victory.

The Black Flags made his march as difficult as possible. Chinese resistance was especially stiff seven miles south of Tuyen Quang, at Hoa-Moc, where the Black Flags had thrown up earthworks. Arriving there on May 2, the relief column drove out the defenders with concentrated artillery fire and a bayonet charge, though at great cost. In fact, more French troops died in the battle than fell during the entire siege of Tuyen Quang. In total, the relief column suffered some five hundred casualties en route to the fort.

With the Black Flags’ defeat at Hoa-Moc, Liu reluctantly concluded that he must end his siege of Tuyen Quang. Thant night his forces silently retreated northward. The next morning, the cratered corpse-covered fields surrounding the fort and the outlying jungle were eerily silent. A patrol of legionnaires led by Captain de Borelli went out to investigate and discovered that the six miles of Chinese trenches that laced around the fort were apparently deserted. At least one group of Yunnanese regulars, however, had remained behind. When the patrol drew near, one of the Chinese soldiers rose up and fired a shot at de Borelli, whose life was saved by one of his legionnaires who threw himself in front of his captain and was fatally wounded.

De Borelli was so moved by the soldier’s selfless act, as well as by the sacrifice of all his legionnaires who fell at Tuyen Quang, that he later wrote an emotional poem dedicated “To my men who are dead, in particular to the memory of Thiebald Streibler who gave his life for mine, the 3rd of March, 1885, Siege of Tuyen Quang.”

Late that day, the relief column finally arrived at the battered fortress. Although appalled at the sight and stench of hundreds of rotting corpses covering the battlefield, the recently arrived soldiers must have been filled with admiration as the heroic garrison stood at attention and saluted them. Of the original 619 defenders, about fifty were dead and two hundred wounded. Sergeant Bobillot would die of his wounds in a Hanoi hospital on March 18.

General de Négrier, meanwhile, had become aware that the Chinese were building up forces on the other side of the Gates of China, and he launched an offensive across the border that the enemy repulsed. The French fell back on Lang Son, which was soon attacked. When de Négrier was seriously wounded, command fell to Colonel Paul Herbinger, who immediately ordered a retreat to the Red River Delta. In the army’s flight, Herbinger ordered all artillery, equipment and even the regimental funds to be discarded. While the French campaign in Formosa had drained manpower and resources and reached a dead end, the debacle at Lang Son was so poorly received in Paris that Prime Minister Jules Ferry was forced to resign.

With the Chinese again on the offensive, French diplomats hastened to fashion an armistice, which was signed on April 4, 1885. By terms of the agreement (and the following treaty of June 11), the Black Flags and the Chinese army were ordered to return to China in exchange for the French abandoning their designs on the Pescadores Islands and Formosa. Somehow France had turned a string of military defeats into Chinese acknowledgement of French sovereignty over Tonkin. The Vietnamese, who had not been consulted, did not accept the new state of affairs, and their subsequent revolt took the French fifteen years to repress, despite using measures of the utmost brutality.

In the aftermath of the siege of Tuyen Quang the courage of the brave legionnaires who defended the citadel was widely extolled in France (with little mention of the Tirailleurs Tonkinois who had fought with them). But while the defenders’ courage was toasted in the cafés of Paris, the Chinese were also celebrating what they regarded as their victory over the French. Although they failed to take Tuyen Quang, the Chinese had inflicted severe losses on French forces in the spring of 1885. Their efforts were taken as evidence of the ability of Chinese fighters to defeat Europeans in the field.

As historian Douglas Porch has pointed out, however, the strategic significance of Tuyen Quang is unclear. The commitment of large numbers of Black Flags and Chinese regulars to the eventually fruitless siege prevented their more useful deployment elsewhere, such as the Red River Delta, while Brière de l’Isle was occupied in the north. The French debacle at Lang Son undermined any support in Paris for a general war with China and probably helped prevent the enormous loss of life that might have resulted from such a conflict.

Liu Yung-fu and his Black Flags later went on to fight bravely but vainly against superior Japanese forces on Formosa. He finished his career chasing bandits in Kwangtu Province and died in 1917 as a hero of Chinese resistance to colonialism.

Captain de Borelli’s poem extolling the virtues of the self-sacrificing foreign soldiers of the Legion who had died for France was poorly received by the upper echelons of the military, and he received no further promotions in a long and active service career. The captain left behind two additional legacies of his service in Tonkin: a pair of black banners seized during the siege of Tuyen Quang, which he donated to the Foreign Legion’s shrine at Sidi Bel Abbès, Algeria, with the condition that they be destroyed if the legion ever left Africa. In accordance with his wishes, the flags were burned in a ceremony in 1962 before the French pulled out of the country, their last major colonial stronghold.

Chinese Oil Rig in South Sudan (Tong Jiang/Imaginechina)

Chinese Oil Rig in South Sudan (Tong Jiang/Imaginechina) While China has had success in securing energy supplies in Africa, its oil offensive is by no means flawless. Chinese corporations working abroad provide little employment for local people and are remarkably tolerant of corruption and human rights abuses. Chinese overseas operations are also notorious for their disregard of environmental considerations. The latter is perhaps unsurprising, considering the environmental devastation afflicting China’s own industrial centers. Yet, the combination of all these factors tends to create unrest in nations where Chinese operations are seen as benefiting members of the ruling elite and few others. What is also notable is that of the five African countries where China is involved in major resource operations, only one, Angola, is not dealing with a major insurgency.

While China has had success in securing energy supplies in Africa, its oil offensive is by no means flawless. Chinese corporations working abroad provide little employment for local people and are remarkably tolerant of corruption and human rights abuses. Chinese overseas operations are also notorious for their disregard of environmental considerations. The latter is perhaps unsurprising, considering the environmental devastation afflicting China’s own industrial centers. Yet, the combination of all these factors tends to create unrest in nations where Chinese operations are seen as benefiting members of the ruling elite and few others. What is also notable is that of the five African countries where China is involved in major resource operations, only one, Angola, is not dealing with a major insurgency.