Andrew McGregor

May 10, 2005

In the midst of growing political tensions between Iran and the United States a Shi’ite rebellion in the remote mountains of northwest Yemen has created suspicions that Iran may be attempting to open a new anti-American front to weaken U.S. efforts in the region. Yemen’s president, Ali Abdullah Salih, has been a resolute ally of the U.S. in the War on Terrorism, but has used the alliance to reverse a once-promising democratic reform process. After a short truce fierce fighting has resumed, as President Salih sought to eliminate resistance from the radical Shi’ite movement. This new conflict follows similar expeditions in the past few years against well-armed groups of Sunni militants.

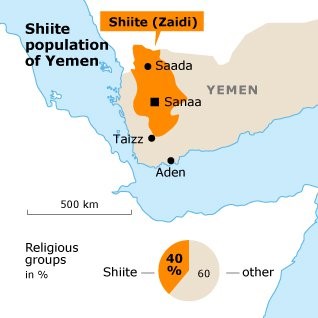

The Zaydi Shi’ites

Yemen’s Zaydi Shi’ites are well known for passionate loyalty to their Imams (traditional dual religious/political leaders) but are regarded as moderate in their practice of Islam. With the reported growth of the rabidly anti-Shi’ite al-Qaeda organization in Yemen, it has been suggested that Iran may intervene in support of the Zaydi Shi’a. In the past, Sunni veterans of the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan were used to control any resurgence of the Zaydi Shi’a, from whom the old royal family was drawn. [1] Zaydi Shi’ism is one of three main branches of the Shi’a movement, together with Twelver Shi’ism and the Isma’ili branch. Unlike the other branches, the Zaydi-s are restricted almost solely to the Yemen area. Their form of Shari’a law follows the Sunni Hanafi school, which aids in their integration with the Yemeni Sunnis.

The Saada uprising has a more traditional character than most of the modern Islamist militant organizations, which are led largely by military veterans and professionals such as doctors and engineers. The mountain revolt is led by a Zaydi religious figure, Hussein al-Houthi, who leads a student movement committed to Islamic reform, the Shabab al-Mu’mineen, “The Young Believers.” Al-Houthi was a member of Yemen’s parliament from 1993-97. Unconnected to the mainstream of Sunni radicalism, al-Houthi is a fierce opponent of al-Qaeda, which cemented its anti-Shi’ite reputation by participating in the Taliban’s massacres of Afghan Shi’ites. Like the Sunni militants, however, al-Houthi’s most scathing invective is reserved for America and Israel, whom al-Houthi alleges are conducting an anti-Muslim campaign throughout the Middle East. Al-Houthi has urged his followers to prepare for a U.S. invasion of Yemen. Democracy is viewed as a trick to complete the Zionist domination of the Arab world. Even among the Zaydis, support for al-Houthi is far from universal; while refuting charges of Iranian support for the insurgency, al-Houthi’s brother, a member of parliament, called the religious leader a “criminal” and an international embarrassment. [2]

Al-Houthi’s insurrection is not aimed at spreading Zaydi Shi’ism, but is rather an expression of dissatisfaction with President Salih’s pro-American policies. Al-Houthi describes President Salih as “a tyrant… who wants to please America and Israel, by sacrificing the blood of his own people,” [3] while the President describes al-Houthi as “sick and mentally abnormal.” [4]

War in the Mountains

The insurgency began June 18. Since then the government has unleashed the full force of its arsenal of jets, armour and artillery to pound the lightly armed “Believers.” On July 23, operations were suspended to allow religious scholars a last chance to cross the lines and convince al-Houthi of the mistakenness of his rebellion. Negotiations with al-Houthi have failed in the past, but with Yemen’s existence relying on a delicate balance of tribal allegiances there is usually a preference for negotiated settlement. Many believe that the President’s insistence on a military solution derives from the rude reception he received on a visit to the mountains earlier this year.

The campaign against al-Houthi was expected to be quick, but the Shi’ite fighters have lived up to their warrior reputation, giving fierce resistance to what should have been an overwhelming government force. Government troops have had to struggle up passes similar to the one where a well-equipped column of 10,000 Sadaa-bound Ottoman troops was wiped out by the Zaydis in 1904. The savagery of the fighting and the number of casualties on both sides (300-400 dead so far) has been a shock to many Yemenis. Though the “Young Believers” are only somewhere between 1,000 to 3,000 in number, many Yemenis believe that al-Hourthi is only giving voice to opinions widely shared in Yemen.

In urban areas like Sanaa, however, there is some disdain for yet another Mahdist-style movement that will come to a bad end for its superstition-fed adherents. Even Abdul Majid al-Zindani, leader of the radical wing of the Islamist Islah party, has warned against the “serious consequences of extremism and all forms of fanaticism, which are the major reason behind the civilizational decline and backwardness of the Muslim nation”. [5] A powerful political figure and a former comrade of bin Laden during the Afghanistan war against the Soviets, al-Zindani has recently been accused of collecting funds for al-Qaeda, only to be strongly defended by President Salih. Like many of Yemen’s clerics, al-Zindani called for a Muslim jihad against American and British troops in the early days of last year’s Iraq campaign.

In urban areas like Sanaa, however, there is some disdain for yet another Mahdist-style movement that will come to a bad end for its superstition-fed adherents. Even Abdul Majid al-Zindani, leader of the radical wing of the Islamist Islah party, has warned against the “serious consequences of extremism and all forms of fanaticism, which are the major reason behind the civilizational decline and backwardness of the Muslim nation”. [5] A powerful political figure and a former comrade of bin Laden during the Afghanistan war against the Soviets, al-Zindani has recently been accused of collecting funds for al-Qaeda, only to be strongly defended by President Salih. Like many of Yemen’s clerics, al-Zindani called for a Muslim jihad against American and British troops in the early days of last year’s Iraq campaign.

The ruling General People’s Congress Party has accused Iran of direct support for the Saada uprising as an effort to create a new front to drain U.S. resources in anticipation of American attacks on Iran and the Hizbullah of southern Lebanon. The President has personally avoided naming Iran, but left little doubt to whom he was referring in making charges of interference by ‘foreign intelligence agencies’. There have also been suggestions that al-Houthi has received financial assistance from the Shi’ite communities of Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. The insinuation of Iranian involvement came only days after the signing of several new economic agreements between Iran and Yemen and the extension of a 10 million Euro credit by Iran following the conclusion of the 7th meeting of the Yemen-Iran Committee, a forum for bilateral relations.

In Yemen’s long civil war of the 1960s, Iran gave financial aid and a small quantity of arms to the Royalist government of the Zaydi Imam, though its contribution was small compared to that of Sunni Saudi Arabia. The Shah’s help had less to do with Shi’ite fellowship than with hindering the regional ambitions of Nasser, who had already deployed the United Arab Republic army on the Republican side. The Republicans were themselves dominated by a mainly Zaydi officer corps and most Shi’ite and Sunni tribes were usually just a bribe away from changing sides. For the most part, the Arab Zaydis of Yemen have continued to evolve in isolation from their Shi’ite brethren in Iran.

Outgoing U.S. ambassador to Yemen Edmond Hall recently expressed satisfaction with Yemen’s anti-terrorist efforts while suggesting that conditions in Saada province made it rife for penetration by elements of al-Qaeda. Hall’s critics in Yemen accuse the ambassador of running autonomous counter-terrorism operations within Yemen, though both the ambassador and the government insist that their operations are fully coordinated. Hall, the survivor of several assassination attempts, was recently described by a Yemen columnist as “the ambassador who did not give a damn for diplomacy.” [6]

Alliance with Saudi Arabia

Efforts have been made to cooperate with Saudi forces in securing the poorly defined and largely unpopulated Yemen-Saudi border in order to prevent the infiltration of Islamist militants fleeing Saudi Arabia’s own crackdown. Saudi Arabia has also long complained of the traffic in arms from Yemen. The Saudis’ construction of a security barrier along the border has outraged opposition groups in Yemen, who compare it to Israel’s wall in the West Bank. Official relations between the Saudi kingdom and Yemen have rarely been closer than they are now. In July, Saudi Arabia returned to Yemen over 40,000 square kilometers (mostly in eastern Hadramawt province) in accordance with the border treaty of 2000. On July 24, both nations exchanged 15 suspected terrorists for prosecution. Questions have arisen over just how far the new Saudi-Yemeni cooperation extends. The Saudis denied charges last month from al-Houthi’s camp that the Saudi Air Force was involved in a joint Yemen-Saudi bombing campaign that destroyed several villages. The death of numerous Zaydi civilians in air and artillery attacks has brought the attention of Amnesty International, which has asked the Yemen Interior Ministry for an investigation.

Conclusion

At the moment there appears to be a movement within some parts of the U.S. administration to identify Iran as a growing threat to U.S. interests, alleging Iranian aid to al-Qaeda before and after the 9/11 attacks. In making ‘links’ between Iran and the Zaydi insurgency there is a tendency to integrate Shi’ite movements within a vertical command structure (with Tehran at the top) that does not accurately reflect historical, social, linguistic, ethnic and even religious differences between the branches of Shi’ite Islam.

Iran weathered similar political storms during the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq with surprising patience, perhaps expecting the U.S. to exhaust itself before it can strike Iran. Despite the encouragement of Israel, the U.S. is unlikely in the short term to take military measures against Iran, a much larger and formidable adversary than Iraq. The usefulness of the Saada rebellion as an Iranian counter-strategy is questionable; the uprising is not large enough to influence the balance of power in the region or to draw away significant American resources in the way a general Sunni rising would. The attractions of militancy to a traditionally conservative and moderate community should sound a warning that the Salih government may be leading Yemen into a period of renewed civil conflict that may easily spill into the international arena.

A more important threat remains from Yemen’s Sunni extremists. On July 1, the Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigade threatened to drag the United States into ‘a third quagmire’ in Yemen (after Afghanistan and Iraq) with the cooperation of local Islamist groups. Yemen’s Sunni radicals played a prominent role in the growth of al-Qaeda; the region may continue to provide an important source of manpower for international terrorist operations. Homegrown militant groups like the Islamic Army of Aden also continue to provide military challenges to the Salih government. With U.S. forces unexpectedly overextended in Iraq, the U.S. has so far avoided a large-scale military commitment in Yemen, preferring to aid the Yemen regime in its own local war against Islamist extremism.

Yemen’s experiment with democracy is withering as Salih, president since 1978, attempts to create dynastic rule at the head of a one-party state. Lately Salih has attempted to reverse the process of integrating Islamists into the government. The pro-US position of the President (and its offer of troops for service in Iraq) is hardly a representation of popular sentiment in Yemen. Salih’s control of Yemen will be sorely tested in the days ahead as the government simultaneously tries suspects in the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole and the 2002 attack on the French tanker Limburg.

Salih has established a pattern of playing off Islamists against Socialists, with the intention of eliminating both as potential opponents of the GPC. While Salih grooms his son as his successor, Yemen threatens to become a replica of the hereditary Ba’athist presidencies of Iraq and Syria. The stifling of democracy and the alienation of Islamists from the political process are contributing factors to the radicalization of Yemen’s Sunni majority. With new challenges from a revival of Southern separatism and the unexpected insurgency in the Zaydi heartland, Yemen has become a new Middle Eastern tinderbox.

Notes

- The Zaydi Imams ruled Yemen from the ninth century until 1962, with interruptions. The Shi’a represent roughly 40% of Yemen’s 20 million people.

- John R Bradley: ‘A warning from Yemen, cradle of the Arab world’, Daily Star (Beirut), July 13, 2004

- ‘Yemeni preacher speaks out against Salih’, Agence France Press, July 22, 2004

- ‘Yemeni President: al-Houthi is an ill man, mentally abnormal’, Arab News, July 9, 2004, arabicnews.com/ansub/Daily/Day/040709/2004070905.html

- Mohammed al-Qadhi: ‘Islah warns of Sa’ada events consequences: Criticism of U.S. accusations against al-Zindani’, Yemen Times, July 23, 2004

- Hassan al-Zaidi: ‘Yemen bids farewell to Ambassador Hall’, Yemen Times, July 26-28, 2004 yementimes.com/article.shtml

This article first appeared in the May 10, 2005 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor