Andrew McGregor

July 31, 2007

As the focus of U.S. justifications for its invasion of Iraq and the subsequent “yellowcake” political scandal, both the African country of Niger and its considerable uranium reserves have become well known since 2002. While claims that Niger was supplying uranium to an Iraqi nuclear weapons program have been refuted, there are new concerns that a growing rebellion in Niger’s north might destabilize the country and its uranium industry, now the third largest in the world.

Fighters of the Mouvement des Nigeriens pour la Justice (MNJ)

Fighters of the Mouvement des Nigeriens pour la Justice (MNJ)

The Tuareg-led rebel group, Le Mouvement des Nigeriens pour la Justice (MNJ), also includes a number of disaffected members of the Tubu, Arab, Peul, Hausa and other nomadic or semi-nomadic groups dwelling in northern Niger. Despite unsubstantiated claims that the Tuareg present a critical North African link to a supposed expansion of al-Qaeda operations to the Sahel region, the MNJ rebellion has no apparent Islamist component. The grievances of the MNJ are nearly identical with the causes of past Tuareg revolts—government corruption, underdevelopment, inequitable distribution of wealth, economic marginalization and ethnic discrimination.

The government of President Mamadou Tandja has responded by restricting press freedom, refusing to negotiate with the rebels and dispatching 4,000 troops to the north (Le Republicain [Niamey], July 1). The final move is not without its own dangers, as there are reports of mass desertions from the military to the rebels (Afriquenligne, July 21). Militarization of the northern region has already brought the vital Saharan tourist trade to a crashing halt, with European charter flights into Agadez canceled until December. The government has also reduced fuel supplies to the north, making it difficult for food to find its way to the market. Although the official reason is to prevent fuel theft by the rebels, the government is no doubt hoping that pressure on the food supply will diminish MNJ popularity in the north.

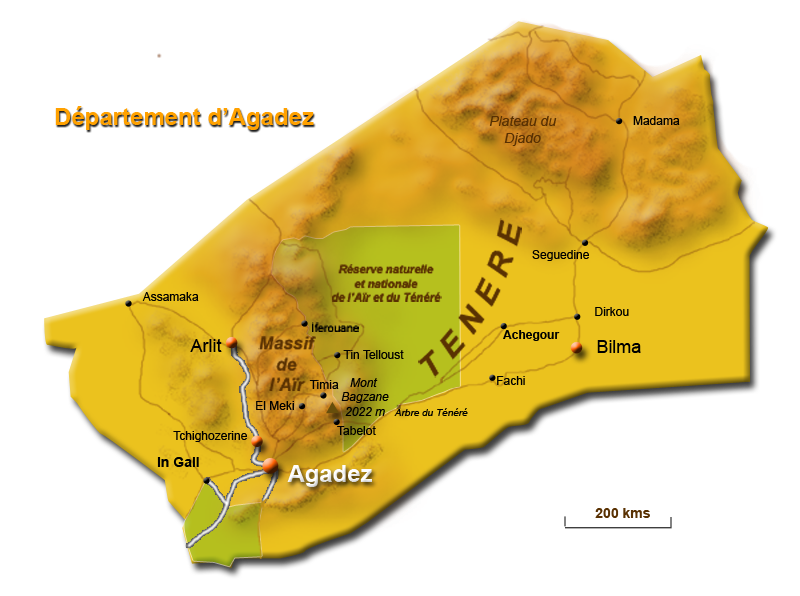

Uranium production in Niger represents 8-10% of the world’s supply (3,400 tons in 2006) and accounts for nearly 70% of the country’s exports. The French discovered uranium in Niger’s Tim Mersoï Basin in 1957, using the metal for its nuclear weapons program. Since then, French uranium concern Areva has developed two major uranium mines at Arlit and Akouta, both in the Agadez region, home of the old pre-colonial Tuareg sultanate. The mines operate as joint ventures with ONAREM (Niger’s state mining concern) and a number of minority interests. Although Niger’s uranium is expensive to produce, it is plentiful—with reserves expected to hold out for several more decades. All Niger uranium is pre-sold to COGEMA (France), ENUSA (Spain) and OURD (Japan). Massive diversions of the metal, such as those claimed by the U.S. administration in 2002, are virtually impossible. The rebellion threatens government plans to double the output of its uranium industry in the next four years to meet a growing demand for nuclear fuels. The cost of uranium has soared from $7 per pound in 2000 to over $130 per pound in 2007. Chinese, Canadian and Indian firms are leading the resulting exploration rush in the Agadez region.

Little of Niger’s wealth in natural resources, which includes other precious metals and petroleum, has reached the people of Niger—recently ranked last in quality of life by a UN development index. Impoverished tent cities, burdened with unemployed Niger citizens seeking work, have developed around foreign mining operations. According to the MNJ, as few as 15% of the jobs are available to locals; they, instead, survive on the crumbs of the foreign-managed facilities. Uranium dust has contaminated pastures and the scarce water sources in northern Niger, and a coal-fired fuel plant provides energy for the mines with few environmental restrictions.

Development of the Ingall region of Agadez, a vital grazing ground for Niger’s pastoralists, is specifically opposed by the MNJ—who expressed their displeasure with China’s efforts in the area by kidnapping an executive of the China Nuclear International Uranium Corporation on July 6 (Xinhua, July 7). Although the worker was later released, all the company’s personnel were withdrawn under military escort to Agadez. According to a MNJ spokesman in Paris, the Chinese are not welcome “because they don’t work with locals, they don’t employ locals, and they respect the environment even less” (Reuters, June 27). The halt in Chinese operations is unlikely to last; China needs fuel for a planned series of nuclear reactors that have been designed to reduce the growing economy’s dependence on coal-fired energy plants. The MNJ claims that the government used fees from exploration permits to buy two Russian Mi-24 helicopter gunships, and it accuses China of providing arms to the Niger military. MNJ leader Aghali ag Alambo states that “We’re not against any firm, be it from China or elsewhere. But we are against companies which supply the national army while that army is directing its force against civilians who are demanding their rights” (Reuters, July 7).

Development of the Ingall region of Agadez, a vital grazing ground for Niger’s pastoralists, is specifically opposed by the MNJ—who expressed their displeasure with China’s efforts in the area by kidnapping an executive of the China Nuclear International Uranium Corporation on July 6 (Xinhua, July 7). Although the worker was later released, all the company’s personnel were withdrawn under military escort to Agadez. According to a MNJ spokesman in Paris, the Chinese are not welcome “because they don’t work with locals, they don’t employ locals, and they respect the environment even less” (Reuters, June 27). The halt in Chinese operations is unlikely to last; China needs fuel for a planned series of nuclear reactors that have been designed to reduce the growing economy’s dependence on coal-fired energy plants. The MNJ claims that the government used fees from exploration permits to buy two Russian Mi-24 helicopter gunships, and it accuses China of providing arms to the Niger military. MNJ leader Aghali ag Alambo states that “We’re not against any firm, be it from China or elsewhere. But we are against companies which supply the national army while that army is directing its force against civilians who are demanding their rights” (Reuters, July 7).

Libya has been accused of supporting the insurrection, likely because of its close ties to Tuareg militants dating back to the Libyan-sponsored Islamic Legion of the 1970s. French uranium miners Areva have also been charged within Niger of supporting the rebel movement, reflecting a common belief in some elements of the ruling class that French sympathies tend to lie with the desert Tuareg rather than the African tribes of the south. Areva denies the charges, pointing to its own financial losses due to rebel activity, including an April 20 attack on an Areva camp that shut down production for a month (Agence France-Presse, April 20). In an effort to quell opposition to the uranium industry, Areva has announced plans to spend over $1 billion on health and environmental concerns in northern Niger (Africast, May 3).

While Areva is moving toward alleviating the impact of its operations, it is yet to be seen whether its concerns will be shared by other foreign operations in northern Niger. Past experience shows that Niger security forces do not have the ability to quash opposition in the area. Unless measures are taken to accommodate the needs of indigenous tribal groups, the risk of heightened radicalization will be unavoidable.

This article first appeared in the July 31, 2007 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Focus