Andrew McGregor

December 22, 2011

In a recent interview with a French-language African news magazine, Djibouti’s head of state, Ismail Omar Guelleh, was asked if “the great wind of the Arab Spring” had “blown as far as Djibouti?” Guelleh, leader of Djibouti since 1999, quickly dismissed the notion: “The Holy Koran talks of ‘summer and winter voyages.’ The notion of spring does not exist in the Arab world” (Jeune Afrique, December 10). [1]

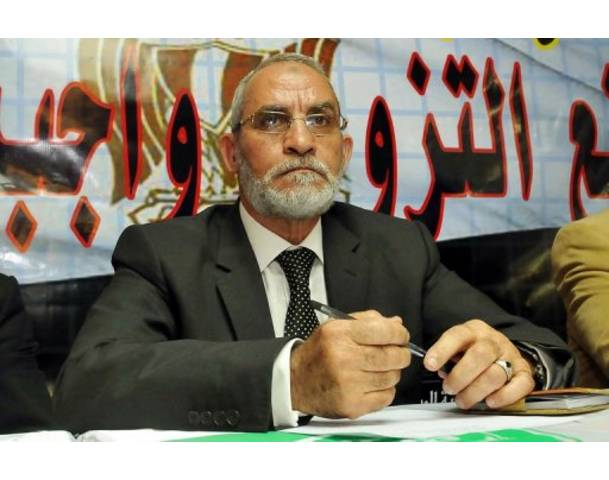

President Ismail Omar Guelleh

The importance of Djibouti to American strategic planning was reinforced this month by a visit to the small African nation from U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta, who said partnerships with nations such as Djibouti were essential to the American counterterrorism effort (AP, December 13). Djibouti is home to the American Combined Joint Task Force – Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA), a mission of over 3000 troops engaged in counterterrorism, anti-piracy, surveillance and humanitarian missions. The Task Force is centered on Camp Lemonnier, a former Foreign Legion installation leased by the United States in 2001. The U.S. facility also serves as a base for CIA-operated drones carrying out missions over Somalia and elsewhere.

Government in Djibouti has been dominated by the ruling Rassemblement populaire pour le Progrès (RPP – People’s Rally for Progress).since independence in 1977. After serving as chief of the secret police, Guelleh succeeded his uncle, Hassan Gouled Aptidon, as the nation’s second ruler in 1999. Opposition leaders are routinely jailed before or after elections, leading to election boycotts in 2005 and in 2011 after Guelleh amended the constitution to allow for a third six-year term. Guelleh had previously promised his second term would be his last. The president justifies his reluctance to share power by citing an excuse used frequently by authoritarian rulers: “This time round, I will not change my mind. I did not want this last mandate. It is a forced mandate, because the people felt there was no one ready to take over” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Djibouti’s Strategic Importance

Djibouti, a small, hot and otherwise insignificant country of 8500 square miles nevertheless occupies one of the most strategic pieces of real estate in the world. Close to many of the major oil-producing regions in the Middle East, Djibouti occupies the western side of the Bab al-Mandab, the southern entrance to the Red Sea and ultimately the Suez Canal. Djibouti is also the place where the great east African Rift Valley meets the Gulf of Aden. The deep, fifty-mile-long Gulf of Tadjoura, protected by the Musha Islands at its entrance from the Gulf of Aden, provides an excellent natural harbor for naval and commercial ships, a fact quickly noted by the French imperialists who arrived in the region in 1862, acquiring the port of Obock from local Sultans as a foothold in the region. The modern port of Djibouti City lies on the southern side of the Gulf of Tadjoura and has historically played a major role in projecting French force and influence into Asia. [2]

Djibouti has played a military role in both world wars, the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in 1936, the Suez War of 1956 (as part of France’s Operation Toreador), the Gulf War of 1991 (as a base of French operations) and now the current conflict in Somalia (including anti-piracy operations).

Until recently, Djibouti was home for 49 years to one of the world’s most famous fighting forces. The 13th Demi-Brigade of the French Foreign Legion was formed in 1941 from legionnaires who rallied to the Free French cause. The unit was initially created to participate in the attack on Narvik in Norway, but later served in heavy fighting on more familiar desert turf in Syria, Eritrea and most notably in Libya at the Battle of Bir Hakeim. During its nine post-war years in Indo-China the unit took terrible losses, particularly at the 1952 Battle of Hoa Binh and the 1954 Battle of Dien Bien Phu. After service in Algeria the 13th was assigned to permanent residence in Djibouti in 1962. After deploying from Djibouti to missions in Somalia, Rwanda and the Côte d’Ivoire, the 13th left Djibouti last June for a new French base in the United Arab Emirates. (Defense.gouv.fr, June 20).

Djibouti is also home to another unique military formation, the 5e Régiment interarmes d’outre-mer (5e RIAOM), the last combined arms (infantry, artillery and armor) regiment in the French army. The 5e RIAOM is the successor of the 5e Régiment d’infanterie de marine (RIMa – colonial infantry), which deployed one company of troops to protect the newly acquired port of Obock in 1890. The unit in one form or another had already participated in the assault on Russian forts in the Baltic Sea during the Crimean War as well as colonial campaigns in China, Mexico and Vietnam. In the 20th century the unit was disbanded and recreated several times under slightly different names while participating in campaigns in the Great War, World War II and the Indo-China War. The unit was re-established as the 5e RIAOM in 1969 with the mission of guarding French interests in Djibouti and being available to support French military operations in Africa or the Middle East. The RIAOM is supported by a section of Gazelle and Puma military helicopters.

An agreement reached in May 2010 allowed the Russian Navy to use port facilities in Djibouti but did not provide for the establishment of a land forces base or permanent Russian naval facility. The agreement allowed Russia to deploy warships in the region on anti-piracy or other missions without the necessity of using supply ships (Shabelle Media Network, May 17; 2010; Interfax, May 17, 2010; see also Terrorism Monitor Brief, May 28, 2010). The first ever visit to Moscow by a Djiboutian Foreign Minister in October highlighted the growing relations between Djibouti and Russia (Buziness Africa [Moscow], October 20; Agence Djiboutienne d’Information, December 13).

Japan has also identified Djibouti as an important asset in the protection of its vast commercial shipping fleet. A Japanese naval base and an airstrip for Japanese Lockheed P-3C Orion surveillance aircraft opened in July as a port for ships of Japan’s Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF). Japan typically deploys a pair of destroyers on rotation in the Gulf of Aden on counter-piracy operations as well as members of the Special Boarding Unit (SBU), a Hiroshima-based Special Forces unit patterned after the U.K.’s Special Boat Service (SBS) (Kyodo News, July 31, 2009; AFP, April 23, 2010).

Djibouti and the Winds of the Arab Spring

Protests against the regime in Djibouti calling for Guelleh’s resignation began at roughly the same time as the Tunisian revolution and the beginning of the Egyptian revolution in late January 2011. Mass arrests of demonstrators quelled the demonstrations by March, but the problems behind the protests remained unresolved (al-Jazeera, February 18; Reuters, March 4). Though Djibouti is not an Arab nation, its proximity to Yemen, its Muslim majority and its membership in the Arab League mean that developments in the Arab world are often influential in Djibouti’s political development.

Guelleh denies the protests had any political motivation, suggesting they were simply an “expression of a purely social malaise, which some big-wigs of the opposition wanted to transform into a revolution… very quickly, it all degenerated into looting… It was, in a much reduced form, the equivalent of [the London riots] in early August. The only difference is that over there, if the media are to be believed, the British police simply restored order when confronted with the urban riots, whereas here we were said to have savagely quelled the peaceful protests” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

A lingering insurgency by the ethnic-Afar Front pour la Restauration de l’Unité et de la Démocratie (Front for the Restoration of Unity and Democracy – FRUD) has survived the 2001 peace agreement that brought an end to a ten-year civil war, with some Afar militants still set on deposing President Guelleh (see Terrorism Monitor, September 25, 2009). The Afar (also known as Danakil after their home territory in northern Djibouti) form roughly a third of the nation’s population, with the majority of the population formed from Somali clans, including the majority Issa (a sub-clan of the Dir) and smaller groups from the Isaaq clan and the Gadabursi, another Dir sub-clan. Religion is not a divisive force in Djibout, with 96% of the population practicing Sunni Isam. The government is dominated by the Issa and to a lesser extent by the Isaaq and Gadabursi, with the Afar having only a small representation in the cabinet. For a time in the 1960s, Djibouti was known by the name “Territoire français des Afars et des Issas,” reflecting a short-lived desire to build a post-independence partnership between the two peoples.

President Guelleh has been accused of repressing dissent and an independent press, but denies these charges: “It is not a problem of censorship, but a problem of money. In Djibouti, there are neither investors nor advertisers in this [media] domain, and the potential readership is very much reduced. Here, people prefer to talk endlessly” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Guelleh regularly derides the opposition in Djibouti as immature and incapable of participating in the democratic process: “In Djibouti the conception of democracy that these gentlemen have is as follows: either one is the head or one seeks to topple the head. They have neither the patience nor the will to take care of the rest” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Development in Djibouti

The majority of Djiboutians live in the port city while the rest tend to live as nomadic pastoralists in the harsh conditions of the countryside. Unemployment ranges between 40% to 50% and provides a source of dissatisfaction with the regime. Other than its strategic location, Djibouti has little to trade on; both resources and industry (other than a small fishing sector) are nearly non-existent.

Djibouti has launched an ambitious $330 million plan to triple its port capacity by 2014 by enlarging the existing container terminal and constructing two new cargo terminals. The port is currently managed by Dubai’s DP World. Much of the new commercial traffic is expected to arrive through a modernized rail line from Addis Ababa and a new rail line from Mekele. Since the loss of Eritrea, land-locked Ethiopia has increasingly relied on a traditional commercial route through Djibouti to the sea. Some 70% of the traffic passing through Djibouti originates in Ethiopia. The main stages in the new rail line from Addis to Djibouti are being built with Chinese financing by the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) and the China Railway Engineering Corporation (CREC) (Reuters, December 17).

Chinese firms are expanding their interests in Djibouti, particularly in the still-nascent energy sector. There is also speculation that Djibouti could be developed as an outlet to the sea for South Sudan (possibly including the shipment of oil products from Chinese companies working in South Sudan) as an alternative to using Port Sudan on the Red Sea in the now separate north Sudan. President Guelleh suggests that China is attentive to Djibouti’s needs in a way that the rest of the international community sometimes is not. Describing Djibouti’s search for assistance in the terrible drought experienced this year, Guelleh notes: “We were asking for $30 million. Four months later, only China made a contribution of $6 million. The rest? They are pledges without any hope of fulfillment” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Djibouti has also obtained Kuwaiti and Saudi funding for the construction of a new container terminal on the north side of the Tadjoura Gulf to relieve congestion in the port of Djibouti and enable the handling of greater traffic from Ethiopia (Agence Djiboutienne d’Information, December 13).

Although Djibouti has not been directly affected by piracy, the phenomenon has led to many ships refusing to come to Djibouti, preferring to use alternative ports to avoid both pirates and rising insurance premiums. Guelleh has urged the international community to address this situation on land in Puntland and Somaliland rather than at sea, where years of international naval activity have failed to deal effectively with the problem (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Djibouti and Somalia

On December 14, Djibouti held a ceremony to mark the long-awaited dispatch of a unit of 850 men and 50 instructors of the 3,500 man Forces Armées Djiboutiennes (FAD) to Somalia to join the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). The force, the first Djiboutian military unit to serve outside of the homeland, is under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Osman Doubad Sougouleh (Agence Djiboutienne d’Information, December 14).

Al-Shabaab has been angered by Djibouti’s hosting of French and American training for troops of the Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and has promised retaliatory strikes within Djibouti should FAD troops arrive in Somalia to aid AMISOM operations (Garowe Online, September 18, 2009). President Guelleh says the nation is remaining vigilant, but “on the other hand, I am not overestimating the Shabaab’s capacity for causing harm; a 2,000 km stretch separates us from their Baidoa stronghold.” Guelleh says he is seeking French military assistance to make Djibouti capable of defending itself, being well aware that French troops do “not want to die for Ras Doumeira [the border territory disputed with Eritrea]” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

President Guelleh has expressed his sympathy for the task set for the TFG in building a new government in an ungoverned nation: “They have nothing. To try to establish one’s authority over a country at war, without revenue, to be constantly solicited [and] harassed by a suffering population is not an easy task” (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Regional Relations

Guelleh is one of the most prominent defenders of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, charged by the International Criminal Court (ICC) with genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity related to the government’s repression of the insurgency in Darfur. According to Guelleh:

Al-Bashir is not what they say he is. He is the only Sudanese leader who has had the courage of negotiating with the south, going as far as amputating his country in the name of peace. Do remember the way those who are opposing him today were treating southern Sudanese as slaves, beginning with [former Sudanese Prime Minister] Sadiq el-Mahdi! They threw this Darfur wrench in [al-Bashir’s] works by inventing a scarecrow of a pseudo-genocide. It was a fable concocted by evangelists and pro-Israeli lobbies (Jeune Afrique, December 10).

Al-Bashir attended Guelleh’s inauguration in May alongside the French Cooperation Minister and the U.S. deputy assistant secretary of state for African affairs, Karl Wycoff (Sudan Tribune, May 8). As a signatory of the ICC Statute, Djibouti was required to arrest al-Bashir but, like Chad and Kenya, Djiboutian authorities have declined to do so.

Djibouti has clashed twice with Eritrea (most recently in 2008) over respective claims to ownership of the Ras Doumeira peninsula along the Eritrea-Djibouti border. In the 2008 border fighting, French troops supplied logistical, medical and intelligence support to Djibouti under the terms of their common defense pact (BBC, June 13, 2008). The opposing forces are now separated in Ras Doumeira by a small Qatari buffer force.

Conclusion

Though Djibouti’s external security is assured by its French patron and the presence of an American military base, internally the situation is different, and the heavy-handed response of the security services seems at odds with the president’s casual dismissal of last spring’s protests as nothing more than “the expression of a social malaise.” It also seems likely that Djibouti’s new commitment to the African Union peacekeeping force in Somalia will invite some type of retaliation from al-Shabaab terrorists who have proven capable of carrying out operations as far afield from their southern Somali base as Kenya, Uganda, Puntland and Somaliland. It seems improbable that Guelleh will be able to survive his new six-year term without substantial internal opposition, though a retaliatory strike by al-Shabaab might play into the regime’s hands, allowing mass arrests and new measures of political repression to ensure Guelleh’s eventual succession, if not by himself, then by other members of his family or the ruling RPP.

Notes

- Guelleh refers here to the Surat Quraysh, the 106th chapter of the Quran, which refers to journeys by the Quraysh tribe (that of the Prophet Muhammad) “in winter and summer.”

- Charles W Koburger, Naval Strategy East of Suez: The Role of Djibouti, Praeger Publishing, 1992.

This article first appeared in the December 22, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

Egyptian Yonca-Onuk MRTP-20 Fast Interceptor

Egyptian Yonca-Onuk MRTP-20 Fast Interceptor