Dr. Andrew McGregor

Military History Online

March 21, 2013

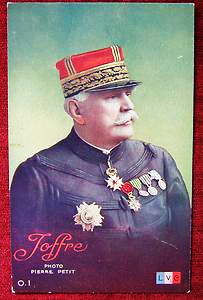

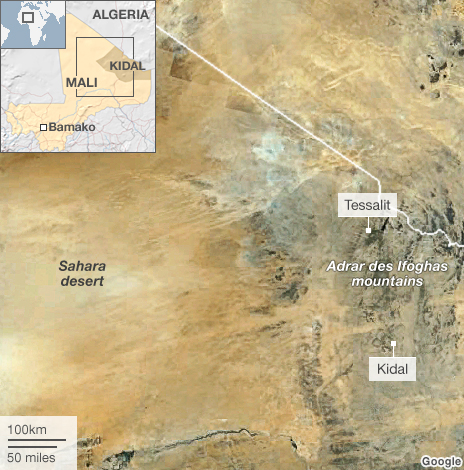

When French troops launched a military intervention against Islamist militants in Mali in January 2013, many of those advancing on the legendary city of Timbuktu may have been unaware that it had been 119 years since a French colonial army column under Major Joseph Joffre had entered that ancient trading capital. Rather than a triumph for France, the 1894 occupation was in fact a planned act of insubordination by Joffre and other French colonial officers. The truth was France didn’t want Timbuktu.

When French troops launched a military intervention against Islamist militants in Mali in January 2013, many of those advancing on the legendary city of Timbuktu may have been unaware that it had been 119 years since a French colonial army column under Major Joseph Joffre had entered that ancient trading capital. Rather than a triumph for France, the 1894 occupation was in fact a planned act of insubordination by Joffre and other French colonial officers. The truth was France didn’t want Timbuktu.

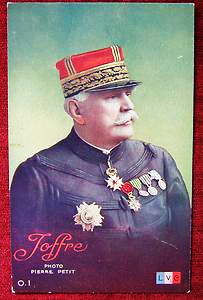

Joffre is best known as the commander of all French armies in World War 1 after his victory at the Marne in 1914 was credited with saving France. At the height of his fame in 1915 his military report of the 1894 occupation of Timbuktu was reprinted under the title My March to Timbuctoo. Unfortunately, Joffre’s account of his campaign along the Niger River disappoints adventure seekers; it is instead a model of dryness and economy of words devoid of personal observations or impressions. Brevity was no doubt called for, as the true story of insubordination, atrocities and war for war’s sake that was behind the conquest of Timbuktu was hardly the material with which to build the reputation of a Marshal of France.

Episodes such as the conquest of Africa have traditionally been envisioned in a haze of flags, bayonets and noble officers falling for the glory of some European power, presumably for the eternal benefit of both the occupier and the occupied. The problem was that the responsible ministries in Paris were often at odds with their armed representatives, the French colonial army. While the government sought profitable colonies in fertile regions of Africa, the army sought a permanent state of war. In the long period of peace France experienced in Europe from 1870 to 1914, combat experience in Africa (or Indo-China) was the only way to make rapid advancement through the ranks. As a result, the French colonial officer corps made their own decisions on expanding French possessions into a far less profitable interior. Failure in these efforts could bring death or dismissal, but punishment of a victorious feat of French arms was a rare occurrence. It was a risk that many colonial officers, including Joffre, were willing to take.

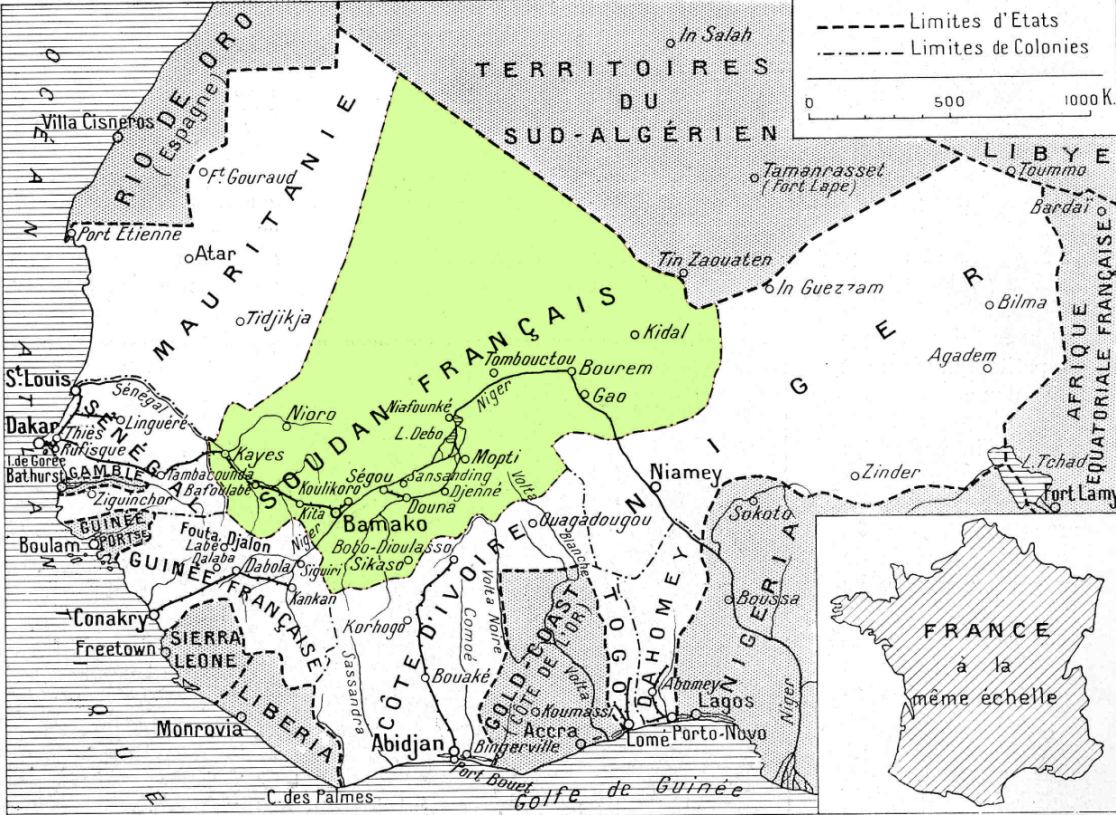

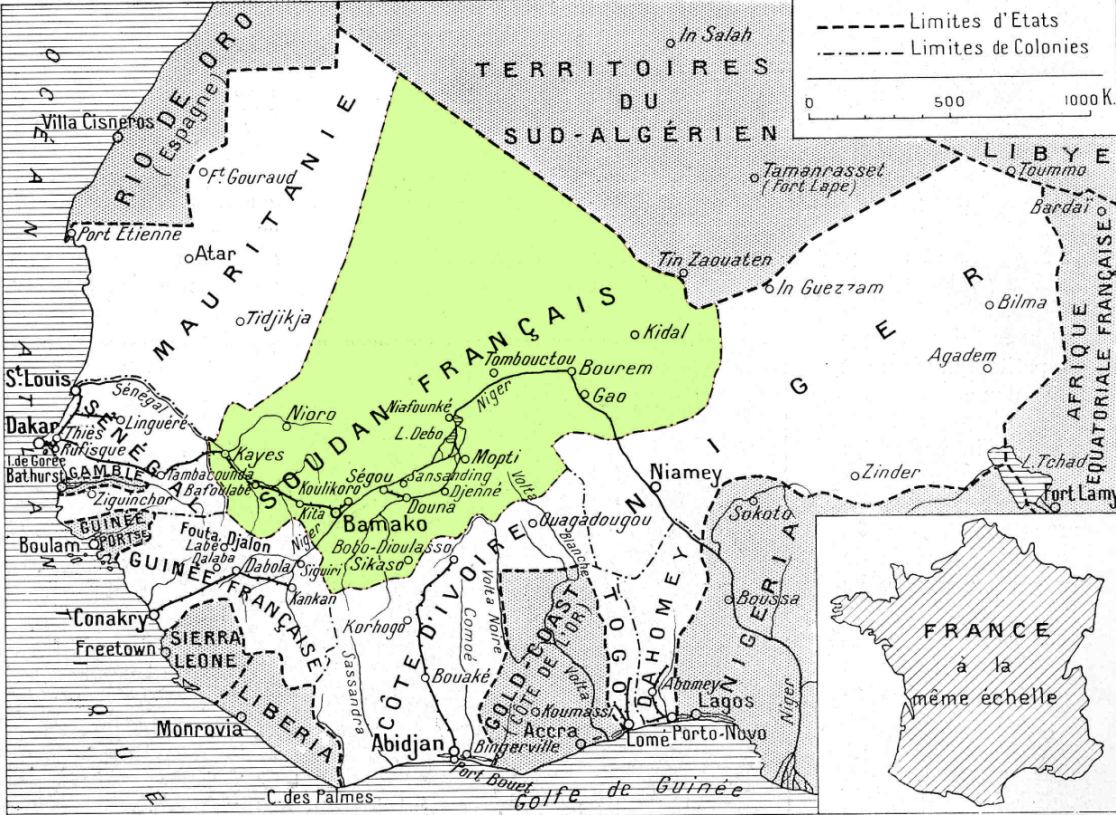

French Soudan – Larger than France

French Soudan – Larger than France

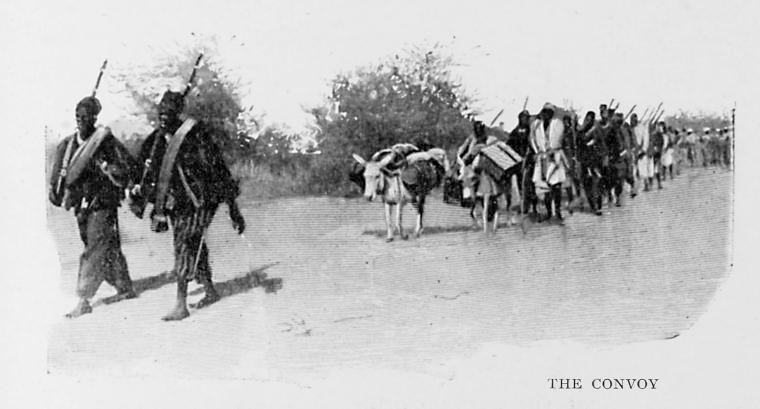

In Joffre’s time, targeted atrocities and summary executions were the tools of the colonial army, regardless of its pretensions at “bringing civilization” or “ending slavery.” African colonial troops joined the army for the prospect of plunder; the official pay was negligible, but war meant an opportunity for self-enrichment and an escape from the drudgery of small-scale agriculture. Women captured on campaign were routinely distributed to the colonial troops before being sold on as slaves. The motivations of France’s young officers were clothed in better fabric on the way out from France, but the realities of how French control was imposed by officers far beyond the supervision of Paris soon made themselves apparent. From that point a young officer had a choice: return to stultifying garrison duty in France or do things “the colonial way” and make a career for oneself in the deserts of Africa.

As a young officer in the engineers, Joffre saw little action in the Franco-Prussian War. France’s military humiliation at the hands of the newly-united Germans in 1871 brought a temporary decline in French pride in its armed forces. The best escape from post-defeat depression and opportunity for advancement was service overseas in the colonial army, which seemed determined to erase the French disgrace of 1871 through a series of aggressive campaigns against little-known peoples in far-off places. Joffre took this route (though his motivation seemed to derive mainly from the early death of his wife) and participated in the two-year battle with China for control of northern Formosa (modern Taiwan) in 1884-85.

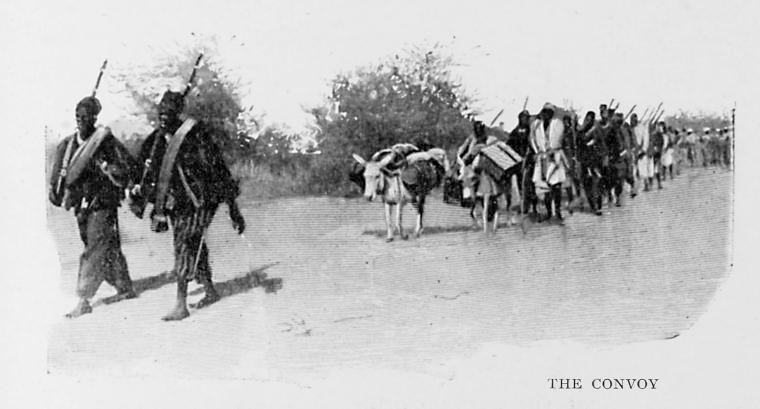

French Column on the March

French Column on the March

When Joffre arrived in 1892 in his new assignment in “French Soudan” (as the French colonies in West Africa were known), he was already marked by a prodigious bulk, an enormous mustache and “a magnificent appetite,” as one of his biographers put it. His orders were to build a railway connecting the Senegal River and the Niger River, but he soon found himself involved in a scheme conceived by his superior officer to take Timbuktu in defiance of official orders. As Lieutenant-Colonel Etienne Bonnier devised his plan to take the city, Joffre became his willing accomplice, commanding an overland invasion column intended to rendezvous with Bonnier’s force, which was to be carried in barges down the Niger. Bonnier left his subordinates orders that the newly arriving civilian governor was to be obeyed in all things, save military matters, on which he was to be ignored. The new governor, Albert Grodet, was a controversial figure in the French colonies but was given the appointment because it was felt he would be tough enough to confront the undisciplined colonels of the Colonial Army head-on. Grodet’s experience as governor of French Guiana , home of France’s vast and lethal penal camps (popularly but inaccurately known as “Devil’s Island”) was doubtless counted in his favor when assessing his ability to tame the colonels.

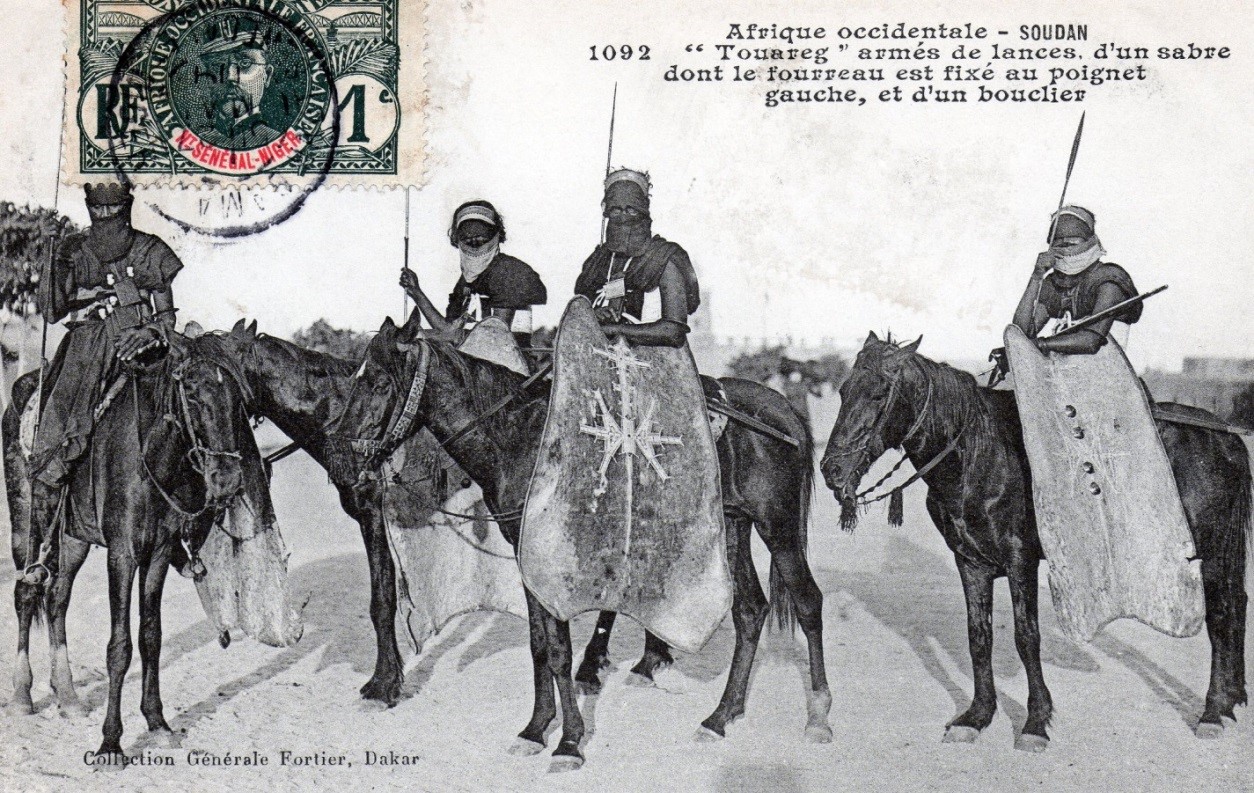

Bonnier and Joffre were preceded to Timbuktu by the gunboats Mage and Niger, under the command of Lieutenant Boiteux, an impetuous young officer who was busy defying Bonnier’s own commands by taking his boats into Timbuktu. Boiteux landed at Kabara, Timbuktu’s port on the Niger, and headed inland with a group of sailors to claim the city for France. A small party of Tuareg appeared but was driven off by the guns of the Mage, directed by the gunboat’s second-in-command, Léon Aube, son of Admiral Aube, the former Marine Minister. The Tuareg scattered and Timbuktu was taken without further opposition.

For Bonnier, however, the rashness of the young lieutenant now gave cover to the unauthorized invasion – Boiteux’s flotilla was in danger in Timbuktu and had to be rescued by the armed columns already under way. A furious Governor Grodet issued new orders for Bonnier to return immediately, but the colonel refused, reassuring the governor that the conquest of Timbuktu would entail no new expenditures to the French purse.

Colonel Bonnier entered Timbuktu in December, 1894, but only stayed there a few days before moving west to join Joffre’s column. By now both Bonnier and Joffre had been sacked by Grodet for insubordination and orders had been issued from Paris for their recall, but Bonnnier cited military necessity as the reason for his continued disobedience. Bonnier had no knowledge of Tuareg tactics and was shadowed by them until the Tuareg pounced on his camp at Goundam in the early hours of a January morning. Bonnnier had not taken even the most basic precautions, such as mounting patrols, posting sufficient pickets or constructing a zariba, a rough fence of thorn brush around the camp. The Tuareg first stampeded the column’s own livestock through the camp to create confusion and then fell on the colonial troops with swords, spears and daggers. Though the Tuareg took losses, the toll of 82 dead in the French camp, including Bonnier and nearly all the European officers, represented a shocking loss and Bonnier was posthumously denounced in Paris for his incompetence. Léon Aube, the second-in-command of the Mage, was killed while leading a small patrol near Kabara on December 28 when a large number of Tuareg descended on his patrol, massacring Aube, the Mage’s French petty officer and 18 laptots (locally raised sailors).

By this time it was clear that French politicians who had supported the establishment of colonies in Africa’s more lucrative coastal regions had lost control of the colonial project to the military, which always discovered one more threat to security in a neighboring territory that would justify yet another military campaign into the interior. In Paris there were new calls for the government to restore discipline in the officer corps of the colonial army, but the occupation of Timbuktu by Joffre’s column was reluctantly recognized as a military achievement and Joffre promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel. Joffre was allowed to remain in the new possession, where he set about the “near annihilation” (as he himself put it) of the Tuareg tribes he believed responsible for the Goundam massacre. For six months after occupying Timbuktu, Joffre defied explicit orders to show restraint in the region by taking revenge on the Tuareg, including tribes not involved in the attack at Goundam. Joffre’s punitive columns carried out large-scale massacres of Tuareg tribesmen and seized their animals to force their submission. The severed heads of opponents of the French occupation began to appear in village markets as a warning that Tuareg domination of the region was over. The slaughter of the Tuareg, who by this time were all considered a threat to the French regardless of their attitudes to the occupation, continued for several years after Joffre’s 1894 departure for new assignments.

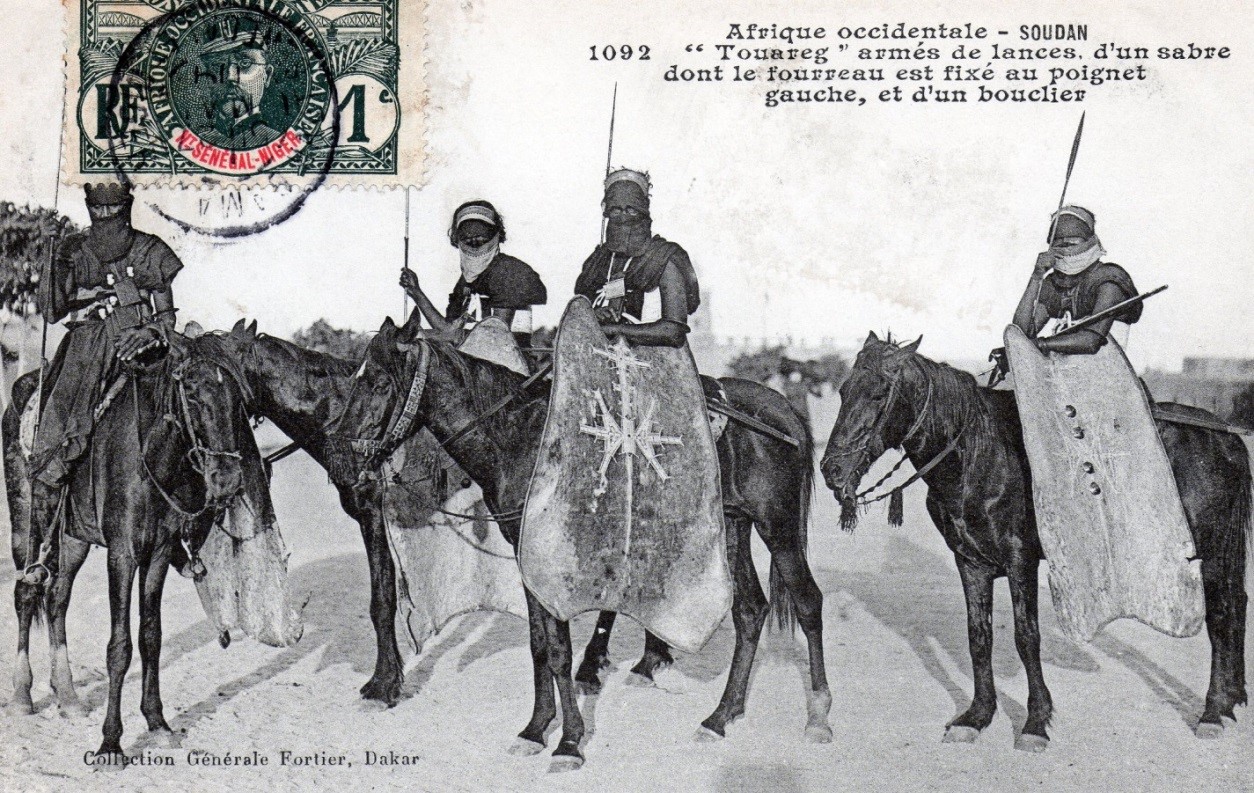

Tuareg Warriors on a French Colonial Postcard

Tuareg Warriors on a French Colonial Postcard

Unfortunately for the Tuareg, their sheer tenaciousness and fighting skills worked against them; ambitious young officers of the colonial army soon recognized that success against the Tuareg brought more recognition than a defeat of lesser tribal warriors. Engaging the Tuareg in battle became more useful to a burgeoning military career than negotiating a peace settlement.

Lieutenant Boiteux, whose arrival in Timbuktu with the Niger River flotilla had made him only the third European to set foot in Timbuktu, survived the campaign, but unlike Joffre, Boiteux was disciplined by the army and committed suicide after an illness in 1897. (By a strange historical coincidence, the first French soldier to be killed in France’s 2013 campaign in northern Mali was Lieutenant Boiteux of the 4ème Régiment d’Hélicoptères des Forces Spéciales [RHFS – 4th Special Forces Helicopter Regiment]). Joffre, however, was feted as the conqueror of Timbuktu and granted an unusual military celebrity unavailable to those who conquered more important but less legendary cities. As for Grodet, he was ultimately unable to control the Marine colonels and eventually fell victim to changing political winds in Paris that brought the militarist faction to power. The governor was blamed for every military failure in French Soudan since his arrival and his often questionable prior service as governor of Martinique and French Guiana was raised in the press and halls of government. It was more than enough to have Grodet recalled in 1895.

The Colonial Army’s brutal methods were not publicly revealed until 1899, when one officer, appalled at the indescribable violence of the infamous Voulet-Chanoine Mission, resigned and described the atrocities in a letter home from Timbuktu that eventually reached the French parliament, where it sparked a national scandal.

By the time Joffre left French Soudan in 1894, he had established his military reputation. He survived the disease-ridden campaign to conquer Madagascar at the turn of the century before being made chief of the French general staff in 1911, despite having no experience at staff work and very little experience of battle. However, Joffre’s lack of political affiliation and absence of any apparent religious tendencies served him well in the highly politicized and sectarian French command.

Joffre took his place as one of the foremost figures of the First World War by denying the German advance on Paris in 1914 at the Battle of the Marne. France had nearly fallen in a matter of weeks due to Joffre’s belief that the Germans would invade France through Lorraine rather than Belgium, but his coolness in command when it appeared the whole French army was on the verge of collapse in the Fall of 1914 brought him the affection of a nation that came to refer to him as “Papa Joffre.” Up to this point, Joffre’s most notable success in “battle” had been his largely unopposed occupation of a small, dusty city in West Africa. As with his success at Timbuktu, controversy over responsibility for the triumph at the Battle of the Marne emerged, with many suggesting it was General Joseph Simon Galliéni’s battle plans that had determined French success at the Marne. Though rewarded with command of all the French armies, Joffre’s devotion to outdated tactics that bled the army white and his removal of most of the guns from the Verdun forts to support ineffective offensives made it clear that the great general was out of his depth. In December, 1916 Joffre was removed from operational command and made a Marshal of France in compensation, bringing a career made on the conquest of Timbuktu to an end.

Joffre came into criticism in his later years for having taken accolades as “the conqueror of Timbuktu.” Bonnier’s brother, a general, wrote a book criticizing Joffre on this point in 1926. When he was given a summary of the work, Joffre is recorded as having remarked; “But yes! It was Bonnier who was the conqueror of Timbuktu… as for me, I guarded it.” It was Joffre’s recognition that it was in fact Bonnier’s obsessive determination to become the conqueror of the legendary city of Timbuktu that unwittingly launched the career of a French military legend.

Bibliography

Desmazes, René: Joffre: La victoire du caractère, Nouvelles éditions Latines, Paris, 1955

Gentil, Émile,: La chute de l’empire de Rabah, Hachette, Paris, 1902

Grevoz, D.: Les canonnières de Tombouctou: les Français à la conquête de la cité mythique 1870-1894, L’Harmattan, Paris, 1992

Hall, Bruce S.: A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600 – 1960, African Studies no. 115, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Henzelin, Émile: Notre Joffre: Maréchal de France, Librairie Delagrave, 1919 Paris, 1917

Jaime, Jean Gilbert Nicomède: De Koulikoro À Tombouctou Sur La Canonniere “Le Mage,” Paris, 1894 (Ulan Press Reprint, 2012)

Joffre, General [Joseph]: My March to Timbuctoo (Operations of the Joffre Column before and after the Occupation of Timbuctoo), London, Chatto and Windus, 1915

Kanya-Forstner, AS, The Conquest of the Western Sudan: A Study in French Military Imperialism, Cambridge University Press, 1969

Kanya-Forstner, AS, “The French Marines and the Conquest of the Western Sudan, 1880-1889,” In JA De Moor (ed.). Imperialism and War: Essays on Colonial Wars in Asia and Africa, Brill, Leiden, 1989

Recouly, Raymond, General Joffre and His Battles, C. Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1917

Taithe, Bertrand: The Killer Trail: A Colonial Scandal in the Heart of Africa, Oxford, 2009

http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/19thcentury/articles/marchingtotimbuktu.aspx

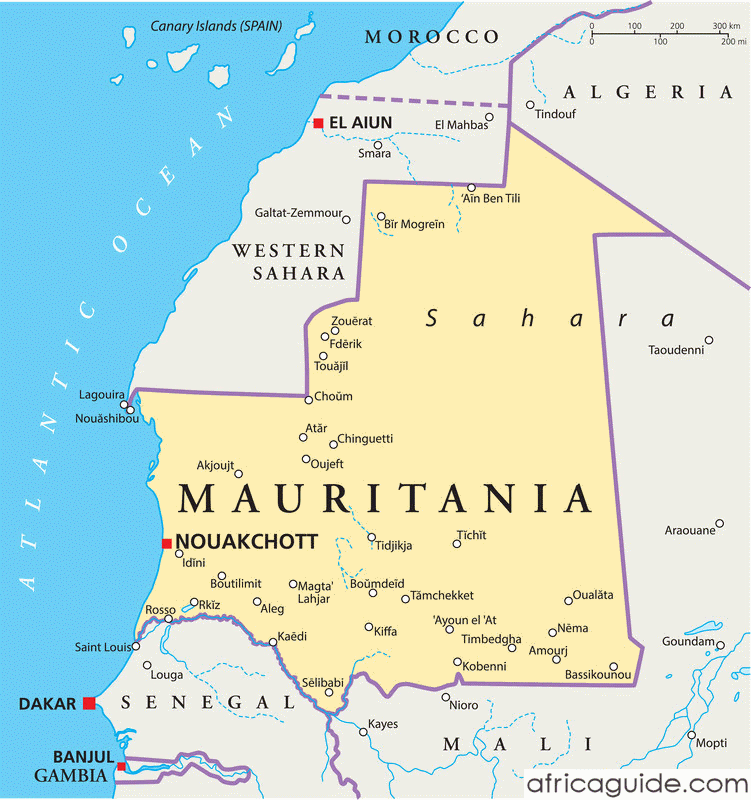

Abu Ayyub al-Mahdi (a.k.a. Ahmad Salim bin al-Hassan), an imprisoned Mauritanian Salafist, announced the creation of a new militant group, Ansar al-Shari’a in the Shanqiti [Mauritanian] Country, on February 12, the latest in a series of autonomous but ideologically sympathetic Ansar al-Shari’a groups to spring up across North Africa and the Middle East.

Abu Ayyub al-Mahdi (a.k.a. Ahmad Salim bin al-Hassan), an imprisoned Mauritanian Salafist, announced the creation of a new militant group, Ansar al-Shari’a in the Shanqiti [Mauritanian] Country, on February 12, the latest in a series of autonomous but ideologically sympathetic Ansar al-Shari’a groups to spring up across North Africa and the Middle East.