McGregor, Andrew: Darfur in the Age of Stone Architecture c. AD 1000 – 1750: Problems in Historical Reconstruction, BAR International Series 1006, Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 53, 2001

Please note the names from the King-lists have not been included in the index.

Footnotes are indexed for content but not citations.

A

Aba Kuri: 96(fn.44)

Abalessa: 14, 14(fn.29)

‘Abbasids: 24, 25, 26(fn.39), 28(fn.65), 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 43, 48, 50, 50(fn.64), 51, 52, 55, 56, 128

‘Abd al-Gadir: 38,

‘Abd al-Karim, Sultan: 44, 45, 56, 77-78, 88

‘Abd al-Karim ibn Yame: 28(fn.65), 43

‘Abd al-Majid, Sultan: 44

‘Abd al-Qadir: 68

‘Abd al-Rahman al-Rashid, Sultan: 96, 96(fn.39)

‘Abdallahi ibn Muhammad al-Khalifa: 62(fn.38)

‘Abdallab Arabs: 50(fn.64), 126

‘Abdullah Gema’a (Jama’a): 126-127

‘Abdullah Wad Hasoba al-Moghrabi: 62(fn.36)

‘Abdullahi Bahur, King: 28

‘Abdullahi Kamteinye, Sultan: 30

Abéché: 45, 77

Abo: 96(fn.44)

Abraham: 36(fn.44)

Abtar: 128(fn.68)

Abu Asal: 88, 95

Abu Delayk: 117

Abu Deleig: 125(fn.37)

Abu al-Fida: 22(fn.4), 23, 52

Abu Garan: 118-119

Abu Hadid: 129, 130

Abu Hamed: 37(fn.46), 124

Abu Hamid al-Gharnati: 38

Abu Haraz: 124(fn.32)

Abu Kundi: 89

Abu’l-Malik: 55

Abu Negila: 116(fn.4)

Abu’l-Qasim: 89, 89(fn.28), 96

Abu Qona’an: 16, 74, 117, 122(fn.6), 123, 128-130, 128(fn.68), 132, 140

Abu Sufyan (Sofyan): 122-124, 127, 127(fn.51), 130, 131, 134

Abu Suruj: 21

Abu Telfan: 23(fn.18), 45, 77

Abu Urug: 125

Abu Zabad: 28

Abu Zayd: 49-52, 52-53, 85

Abu’l-Sakaring Dynasty: 50

Abunjedah: 54

Al-Abwab: 37, 37(fn.46), 129, 129(fn.78)

Abydos: 25

Abyssinia, Abyssinians: 26(fn.38), 38, 111(fn.12), 129, 129(fn.79)

Acien, Kwanyireth Bol: 75

Adams, William Y.: 68, 123, 132(fn.5), 134

Al-Adayk: 49

Addison, F.: 122

Adelberger, J.: 64(fn.57)

Adimo (Dimo): 75

Adindan: 68(fn.97)

Ador, King: 37, 129

‘Agab, King: 85

Agadez: 137

Agadez Chronicle: 130

Agathermerus: 16

Agumbulum: 130

Ahaggar: 13(fn.26)

Ahl al-Awaid: 86

Ahmad Adam: 36

Ahmad al-‘Abbasid: 50

Ahmad Arbaf, Faki: 35

Ahmad Bakr, Sultan: 88-89, 93(fn.10), 95, 96, 96(fn.44)

Ahmad al-Daj: 25, 26, 27, 27(fn.45), 28, 29, 30

Ahmad al-Dia: 29

Ahmad Hamid: 61, 62(fn.37)

Ahmad al-Kabgawi: 27

Ahmad Kanjar: 45

Ahmad al-Ma’qur: 10, 18, 44, 46(fn.31), 49-56, 50(fn.60), 84-85, 87, 112(fn.26), 139

Ahmad al-Turkan: 28

Aidhab: 65

Ainyumba Daifani: 116

Aïr: 113, 130, 137

Akec La, Queen: 75

Akurwa: 75(fn.2)

Alans: 36(fn.44)

Albanians: 74

Albinism: 129, 129(fn.86)

Alexander the Great: 29, 36-39, 36(fns.44-45), 37(fns.51-52),

Alexandria: 126(fn.44)

Algeria: 13-14, 20,

‘Ali, A. Muhammad: 9

‘Ali Ahmad: 119(fn.36)

‘Ali Dinar (Sultan): 4, 11, 11(fn.s 10, 11), 12, 34(fn.26), 34(fn.29), 35, 43(fn.3), 45(fn.23), 54, 57(fn.5), 62(fn.38), 69, 78(fn.14), 96, 96(fn.38), 96(fn.40), 116, 116(fn.1)

‘Ali Dunama: 72

‘Ali Ghaji Zeinama: 72

‘Ali ibn Ahmad, Sultan: 72

‘Ali Korkorat, Sultan: 59, 59(fn.15)

‘Ali Musa: 45

Almásy, László Ede: 127(fn.57)

Almohads: 52

Almoravids: 110(fn.1)

Alwa (Aloa): 37(fn.46), 62(fn.36), 122, 123, 126(fn.44), 127, 131

Ama Soultane: 77

‘Amara Dunqas: 126

Ambus Masalit: 78(fn.14)

Amdang: 86

Aminu, Muhammadu: 16

Ammon: 37, 37(fns.53-54), 38

Ammon (place-name): 128

Amsa, Queen: 72

Amun-Re: 37

Anakim: 128

‘Anaj (Anag, Anak): 48(fn.53), 117, 122, 122(fn.6), 123-131, 123(fn.12), 124(fn.32), 125(fns.37,38), 127(fns.57,58), 128(fns.60,68), 130(fn.92), 140

Andal: 29

Andalus: 48

Anderson, AR: 37(fn.50)

Anedj: 129

‘Angarib, Sultan: 26, 27

Anglo-Egyptian Condominium: 12, 13, 27, 27(fn.52), 62(fn.42), 79, 124

Ani, King: 129, 129(fn.77)

Annok: 36(fn.41)

Anthony: 13(fn.26)

Arab, Arabs: 17, 18, 24(fn.25), 26, 28(fn.65), 31(fn.5), 36(fn.44), 43(fn.6), 44, 44(fn.8), 45, 45(fn.23), 48, 49, 50(fn.60), 53(fn.90), 55, 56, 57(fn.2), 62, 63(fn.47), 72(fn.128), 87, 88(fn.18), 89, 111, 111(fns.11,12), 116, 117, 119, 125(fn.33), 125(fn.37), 126, 128(fn.68), 129, 130, 139

Arabia: 2, 26(fn.38), 27, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 38, 50, 117, 135, 136

Arabic: 11(fn.11), 13, 44(fn.13), 63, 64(fn.54), 71(fn.119), 73(fn.142), 75(fn.7), 77(fn.9), 96(fn.41), 97, 104, 109, 110(fn.1), 111(fn.11), 117(fn.15), 140

Arari: 96(fn.41)

Arin Dulo: 31

Arkell, AJ: 1, 7-9, 12, 16, 20, 21, 23(fn.16), 25, 26, 27, 29(fn.69), 31, 31(fn.6), 33, 33(fn.18), 34, 34(fn.25), 34(fn.30), 36, 36(fn.39), 38, 38(fn.57), 44(fn.13), 45, 45(fn.21), 46, 46(fn.31, 32), 46(fn.35), 47, 48, 50, 53(fn.90), 54, 56, 57, 57(fn.1), 59(fn.9), 60, 60(fn.24), 61, 62, 62(fn.37), 63, 63(fn.49), 64, 64(fn.53), 65, 65(fn.67), 66-69, 68(fn.97), 69(fns.101,102), 70-71, 70(fn.111), 71(fn.118), 72, 72(fn.129), 74, 75, 75(fn.7), 78(fn.14), 91(fns.2,3,7), 93, 93(fn.8), 94, 94(fns.21,22,27), 95, 96(fns.39,41), 97, 97(fn.46), 112, 112(fn.21), 113, 115, 116, 116(fn.4), 117, 118, 122(fn.6), 123, 123(fn.13), 127, 128, 130(fn.96), 132, 134

Arianism: 137

Arlas: 128(fn.68)

Armenia, Armenians: 52(fn.79)

Armi Kowamin: 64(fn.53)

Ary: 129

Asben: 130

Ashdod: 128

Ashmolean: 65

Assyrian: 8, 28(fn.65)

Aswan: 110, 116, 137

Asyut: 5, 125

Atbara: 88, 116, 131

Aule: 63

Aurès: 20

Aurungide Dynasty: 116

Awlad Mahmud: 130

Awlad Rashid: 72(fn.128)

Awlad Sulayman: 44, 63(fn.47)

Axum: 113

Ayesha: 55

‘Ayn Farah: 33, 36(fn.39), 54(fn.99), 56, 57(fn.5), 61, 64-74, 64(fn.60), 65(fn.67), 66(fn.75), 67(fn.86), 69(fn.100), 69(fn.102), 91(fn.3), 112, 122, 127, 131, 132, 134, 137, 139

‘Ayn Galakka: 55, 66(fn,75), 73-74, 73(fns.146,148), 128(fn.68)

‘Ayn Siro: 60(fn.23)

‘Ayn Sirra: 72(fn.129)

Ayyubid: 23

Axum, Axumites: 8

Azagarfa: 96(fn.41)

Al-Aziz, Caliph: 52(fn.79)

B

Babaliya: 48,

Babylon: 22

Bachwezi: 18

Bacquié, Captain: 134

Badanga Fur: 71

Badar: 136

Badi, Sultan: 87

Badr al-Gamali al-Guyushi: 52(fn.79)

Bagari: 116

Baghdad: 50, 52

Bagirmi: 5, 7, 27(fn.55), 43, 62, 63, 75(fn.3), 88, 95, 111, 111(fn.11), 119, 135

Bagnold, RA: 116

Bahar: 91

Baheir Tageru: 125

Bahnasa: 43(fn.6)

Bahr, Wazir: 89

Bahr al-Arab: 27(fn.55), 75

Bahr al-Ghazal (Chad): 67(fn.86), 73, 74, 132-135, 132(fn.1)

Bahr al-Ghazal (South Sudan): 23, 25, 27(fn.45), 27(fn.55), 29, 31(fn.5), 33(fn.12), 75, 128(fn.68), 132(fn.1)

Bahr al-Jamal: 56

Baiyuda Wells: 124

Balal: 111(fn.11)

Balfour Paul, HG: 1, 8(fn.19), 17, 20, 26-27, 28, 31, 35, 36(fn.41), 38(fn.60), 44, 60, 60(fn.24), 61, 61(fn.29), 62, 65, 66, 66(fns.75,77), 68(fn.92), 69, 70, 72, 95

Banda: 7, 27(fn.55)

Bani Abbas: 48

Bani Habibi: 16

Bani Mukhtar: 16

Bantu: 27(fn.55)

Banu Hillal: 44, 46(fn.31), 48, 48(fn.53), 49, 51, 51(fn.71), 52, 52(fns.79, 80), 52(fn.86), 53, 57(fn.2), 85, 117, 120(fn.46), 129

Banu Sulaym: 52, 52(fn.79)

Banu Ummaya: 64(fn.53)

Bao: 49

Baqqara: 24, 27(fn.55), 44, 50(fn.60)

Barah (Bazah): 129

Barakandi: 31(fn.6)

Barani Berbers: 128(fn.68)

Barboteu, Lieutenant: 48

Barca: 64

Bargala: 57(fn.1)

Bariat: 55

Barkindo, BM: 46, 46(fn.30), 47, 111(fn.12), 136, 136(fn.32), 137, 137(fn.41)

Barqat Umm Balbat: 124

Barquq, Sultan: 111(fn.12)

Barr: 128(fn.68)

Barr ibn Qays ‘Aylan: 38

Barra, Battle of: 54

Barrjo: 31(fn.4), 128(fn.68)

Barth, Heinrich: 5, 43, 43(fn.6), 46, 46(fn.27), 57(fn.2), 111

Basa: 129(fn.78)

Basi: 28(fn.60)

Basigna: 119(fn.37)

Batálesa: 43, 43(fn.6)

Batnan, King: 85

Bayko: 23, 23(fns.17, 19), 25, 25(fn.29), 27(fn.45), 29, 88

Bayko King-List: 42

Bayt al-Mayram: 61, 69, 69(fn.102)

Bazina à degrès: 20, 20(fn. 22), 118(fn.27)

Beaton, AC: 16, 87, 87(fn.9)

Bedariya: 128

Bedde: 63

Befal: 129

Beja: 22, 132

Beliin: 137

Bell, Herman: 130(fn.92)

Bender, Lionel M.: 6, 23, 119(fn.34), 128(fn.60)

Bénesé: 43, 43(fn.6)

Benghazi: 77(fn.1)

Beni – see Bani

Benoit Pierre: 13, 13(fn.26)

Berber, Berbers: 7, 13, 14, 14(fn.29), 16, 17, 17(fn.15), 20, 21, 25, 26, 33, 36(fn.44), 38, 45(fn.25), 46, 46(fn.27, 30, 31), 48, 48(fn.53), 49, 52, 53, 53(fn.90), 57(fn.2), 61(fn.31), 62, 64(fn.53), 70, 72(fn.129), 77, 80(fn.2), 111(fns.11,12), 119, 122, 122(fn.6), 123, 125, 125(fn.33), 128, 128(fn.68), 129, 130, 130(fn.93), 137, 139

Beri: 23

Beringia, Battle of: 45(fn.23), 62(fn.42)

Berre, Henri: 24, 25

Berti: 33, 64, 116, 118-119, 119(fn.34), 120(fn.44)

Bayuda Desert: 125

Bible: 37(fn.52), 128

Bidayat: 27, 48, 48(fns.53, 54), 49, 49(fn.55), 72(fn.128), 117, 128(fn.68), 137

Bidayriya Arabs: 88(fn.18)

Bilaq: 33, 33(fn.22)

Bilia Bidayat: 137

Bilia Bidayat, Sections: 48

Bilma: 46

Biltine: 45

Binga: 7, 27(fn.55)

Bir Bai Depression: 77

Bir Natrun: 22(fn.1)

Birged (Birked): 51, 51(fn.71), 64, 64(fn.54), 88, 120, 120(fn.46)

Birged Sections: 120(fn.46)

Biriara Bidayat, Sections: 49

Birni: 56, 72(fn.134)

Bivar, AH: 11, 67(fn.86), 73(fn.144), 74

Blemmyes: 127(fn.58)

Blue Nile, Blue Nile Province: 7, 62(fn.36), 117

Bochianga: 132, 132(fn.7)

Bora Dulu: 9

Bordeaux, General: 73(fn.146)

Borgu: 135, 136

Borku: 44, 66(fn.75), 73, 74, 77(fn.1), 128, 132(fn.4), 137

Borno (Bornu): 5, 7, 11, 16, 16(fns. 4,7), 26(fn.39), 28, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 36(fn.44), 44, 46, 46(fn.27), 47, 47(fn.43), 48, 50, 50(fn.64), 51, 54, 57(fn.2), 63, 69(fn.101), 70, 70(fns.111,116), 71, 72-73, 72(fns.129,135), 74, 75, 75(fn.3), 77(fn.1), 80(fn.1), 88, 91, 110, 111, 111(fns.11.12), 112, 118, 119, 123, 127, 131, 137, 139

Bosnians: 74

Botolo Muhammad: 119(fn.36)

Brahim (Sultan): 44

Brands: 25, 46(fn.37), 70, 70(fn.107), 72(fn.129)

Braziers: 134

Brett, Michael: 52

Bricks, Brick Construction: 65(fn.67), 66, 66(fn.75), 67(fn.86), 70(fn.109), 72-73, 73(fns.142,143,144,148), 74, 95, 96, 114, 122, 124, 126, 127, 132

Britain, British: 11(fn.10), 13, 45(fn.23), 62(fn.42), 65(fn.67)

British Columbia: 15

Brown, Robert: 111

Browne, WG: 5, 46(fn.37), 114, 130

Bruce, James: 38(fn.58), 89(fn.28)

Brun-Rollet: 52

Buba: 15

Budge, EA Wallis: 127(fn.58)

Bugiha: 137(fn.37)

Bugur, King: 29, 31

Bukar Aji: 136(fn.32)

Bulala: 44, 48, 56, 67(fn.86), 70, 73, 73(fn.143), 110, 111, 111(fn.11), 112, 112(fn.21), 137

Bulgi: 57(fn.1)

Burgu Keli: 57(fn.1)

Burnus: 128(fn.68)

Burundi: 115

Busa: 135

Bussa: 136

Butana: 130

Butr Berbers: 128(fn.68)

Byzacena: 137

Byzantium, Byzantines: 43(fn.6), 135, 135(fn.21), 137

C

C-Group: 45(fn.21), 132(fn.7), 134

Cailliaud, Frèdèric: 38, 46(fn.37)

Cain: 128

Cairo: 11(fn.9), 52, 52(fn.79), 63, 64, 78(fn.15), 111, 111(fn.12)

Cameroon: 5, 115, 136(fn.32)

Campbell, E.: 60

Canaanites: 128, 128(fn.68), 132

Canary Islands: 37, 130, 37, 130(fn.93)

Cannibalism: 78(fn.14)

Capot-Rey, MR: 132(fn.5)

Carbou, H: 27(fn.54), 44(fn.8), 46(fn.32), 53, 80(fn.1), 111-112

Carrique, Captain: 73-74, 128(fn.68)

Carthage, Carthaginians: 14, 115, 137

Caucasus: 35, 36(fn.44)

Celts: 36(fn.44)

Central African Republic: 27(fn.55)

Chad: 7, 17, 22, 23, 27(fns.54,55), 31(fn.5), 44, 44(fn.13), 45, 48(fn.51), 66(fn.75), 67(fn.86), 72, 111(fn.9), 112, 113, 114, 132-137, 132(fn.7), 140

Changalif: 45

Chapelle, Jean: 44, 48

Chittick, HN: 125-127

Chokhorgyal Monastery: 35

Chosroe II (Chosroes, Khosraw, Kisra): 26(fn.38), 135, 135(fn.25)

Chouchet Tomb: 14, 14(fn.27), 20, 20(fn.21), 77, 118, 118(fn.27), 119, 119(fns.40,41,42)

Christianity, Christians: 8, 11, 23, 33, 36(fn.44), 38, 44(fn.13), 46, 46(fn.31), 46(fn.35), 46(fn.37), 47, 46(fn.37), 62(fn.36), 64(fn.54), 65(fn.67), 66, 67, 67(fn.86), 68-69, 69(fn.102), 70, 72(fn.129), 74, 110, 111, 112, 116, 117, 120, 120(fn.48), 122-123, 124(fn.29), 125-127, 126(fn.44), 130, 131, 132-137, 132(fns.4,6), 137(fn.41), 139-140

Chronicle of John: 137

Circassians: 74

Clapperton, H: 110(fn.3)

Clarke, Somers: 68

Cleopatra: 13(fn.26)

Cline, Walter: 48(fn.47)

Cohanim: 15

Cohen, Ronald: 11

Congo: 27(fn.55), 33(fn.12)

Copts (Egyptian): 111, 112, 123, 126(fn.44), 132, 135

Crawford, WF: 27, 38(fn.58), 123, 123(fn.13)

Crete: 38(fn.58)

Cromlech: 31(fn.10)

Crowfoot, JW: 130

Cunnison, I: 24

Cuoq, Joseph M.: 77(fn.9)

Currie, James: 46(fn.37)

Cyrenaïca: 37, 64, 77, 117

Cyrus the Great: 37(fn.52)

D

Dagio: 63

Dahia: 29

Daima: 114

Daju: 5, 6, 6(fn.6), 8, 12, 16, 18, 22-42, 22(fn.44), 23(fns.15, 16, 18, 19), 24(fn.21), 27(fn.45), 27(fn.52), 27(fn.54), 28(fn.58), 29, 29(fn.66-67, 71-72), 30, 30(fn.75,77), 31-42, 31(fn.6), 33, 33(fn.18), 34, 34(fn.25), 34(fn.29), 35, 36, 36(fn.45), 43, 44, 45, 51, 53(fn.98), 64, 64(fns.54,60), 72(fn.128), 75(fn.3), 87(fn.9), 91, 110, 112, 118, 118(fn.19), 128, 131, 139-140

Daju Hills: 27, 34, 113(fn.1)

Daju King-Lists: 40-42

Daju Sections: 24

Dak, son of Nyikango: 75

Dakin al-Funjawi: 88(fn.18)

Dakka: 116

Dala Afno (Dali Afnu, Afuno): 44, 70, 75, 91

Dala Gumami, Mai: 72

Dalatawa: 44

Dali: 31, 51, 54, 62-63, 71, 71(fn.118), 75, 75(fn.7), 76, 84, 87, 91, 93, 93(fn.10), 97(fn.45), 112(fn.26), 139

Dalloni, M: 119(fn.42), 130

Damergu: 47, 47(fn.46)

Danagla: 117

D’Anania, Giovanni Lorenzo: 63-64, 71

Danat, King: 29

Daoud al-Mireim, Sultan: 45

Dar Abo Dima: 51, 128

Dar Abo Uma: 51

Dar Birked: 89

Dar Dali (Daali): 62(fn.42), 75(fn.7)

Dar Dima: 75(fn.7)

Dar Erenga: 36(fn.41)

Dar Fertit (Fartit): 29, 112(fn.24)

Dar Fia: 87, 95

Dar Fur (see Darfur)

Dar Furnung: 43, 54, 64, 64(fn.60), 70, 72, 72(fn.129), 75, 86, 139

Dar al-Gharb: 75(fn.7)

Dar Hamid: 119

Dar Hawawir: 125

Dar Humr: 50, 50(fn.61)

Dar Kerne: 95

Dar Kobbé: 27(fn.45), 28(fn.65), 34(fn.25)

Dar Masalit: 30, 36(fn.41), 78(fn.14), 86

Dar Qimr (Gimr): 34(fn.25), 36(fn.41), 44, 45, 95

Dar al-Riah: 75(fn.7)

Dar Runga: 62(fn.42)

Dar Sila: 6(fn.6), 12, 23, 23(fn.18), 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 29(fn.72), 30, 34(fn.25), 36(fn.41), 45, 56

Dar Simiat: 33

Dar Sinyar: 44

Dar Tama: 27, 27(fn.45), 29(fn.72), 45, 79

Dar Tokonyawi: 75(fn.7)

Dar Tuar: 50, 34(fn.25), 50

Dar Uma: 75(fn.7)

Dar Wona: 29, 31, 93, 93(fn.10)

Dar Zaghawa: 33(fn.18), 50, 64(fn.53), 112, 112(fn.24)

Dar Ziyad: 44

Daranga Fur: 78(fn.14)

Darb al-Arba’in: 4, 5, 50, 60, 110, 112, 112(fn.25), 122(fn.6)

Dardai: 47, 47(fn.46), 48, 48(fn.51)

Darfur, Administrative Divisions: 75(fn.7)

Darfur, Geography of: 2-4

Darfur, Trade Routes: 4, 73, 77(fn.1)

Darsala: 47, 47(fn.46)

Date Palm Cultivation: 36, 48, 80(fn.2),

Daud Kubara ibn Sulayman: 129

Da’ud al-Mirayn: 77

Dawa: 57

Dawurd al-Miriri al-Modaddan, Sultan: 55

Daza Tubu: 16, 16(5), 34(fn.29), 45, 47, 137

Dazaga (Dazagada): 44(fn.13), 45

De Breuvery, J: 30, 50

De Cadalvène, E: 30, 50

De Lauture, PHS D’Escrayac: 87

De Medeiros, F.: 17

De Neufville, RL: 65, 65(fn.61), 66(fns.74,75), 67(fn.87), 68, 69(fn.100)

Debba: 31, 31(fn.4)

Debeira East: 67

Debeira West: 65, 65(fn.67)

Delil Bahar: 51, 63

Demagherim: 46(fn.27), 54

Dengkur: 34(fn.26)

Denham, D.: 72, 110(fn.3)

Derdekishia: 47-48

Dereiba Lakes: 34-36

Derihurti: 47

Dhu’l-Adh’ar: 39

Dhu al-Manar: 38

Dhu Nowas: 136

Dhu al-Qarnayn (see Alexander the Great)

Diab, Sultan: 45

Diffinarti: 68

Diffusionism: 8

Dilling: 75

Al-Dimashqi: 123

Al-Dinawari: 37

Dingwall, RG: 63, 65

Dinka: 128

Dionysus: 37(fn.50), 38

Dirku: 16

Dirma: 57

Divine Kingship: 35, 113, 139

Diyab: 49

Djelil al-Hilali: 84(fn.3), 85

Djourab: 132

Dolmens: 118(fn.27)

Donatism: 137

Dongola: 23, 43, 52(fn.86), 67(fn.86), 85, 117, 122(fn.6), 123, 129, 134

Dowda: 57, 57(fns.1-2), 60

Drums (see Nahas)

Dukkume, Malik: 87

Dulo Kuri: 57, 91-93

Dumont, Henri J.: 60(fn.18), 118-120

Dumua: 64(fn.60)

Durma: 57(fn.5)

Duros: 47

E

Edmonds, JM: 123, 125

Edwards, WN: 116(fn.1)

Egypt, Egyptians: 5, 7, 8, 11, 25, 33(fn.22), 38, 43, 52, 52(fn.79), 53, 54, 60, 63, 63(fn.47), 64, 71, 74, 88, 97, 110, 111(fn.12), 112, 112(fn.25), 113, 122(fn.6), 123, 123(fn.16), 125, 127, 128, 128(fn.67), 129, 131, 132, 134, 135

Eilai: 125

England, English: 54

Ennedi: 8, 27, 36(fn.39), 44, 44(fn.15), 46, 48(fn.54), 55, 77, 128, 128(fn.68), 137

Eparch: 38(fn.59)

Equatoria: 33(fn.12)

Erenga: 36(fn.41), 79

Errè: 45

Et-Terge Masalit: 78(fn.14)

Ethiopia: 37, 128(fn.68)

Eunuchs: 20, 57(fn.2), 62, 62(fn.42), 76

Evans-Pritchard, EE: 7, 75(fn.2)

F

Fara: 54

Faragab: 129

Farafra Oasis: 52(fn.80)

Faras: 38, 67, 69

Fashir: 75(fn.3), 89

Al-Fashir: 5, 9, 11, 11(fn.9), 34(fn.26), 45, 45(fn.23), 50, 62(fn.38), 63(fn.47), 69, 75(fn.3), 78(fn.14), 120(fn.46), 135

Fatimids: 52, 52(fn.79)

Fazughli: 27, 38, 128

Fazzan (Fezzan): 5, 20(fn.22), 45(fn.23), 48, 48(fn.51), 119(fn.41)

Felkin, RW: 34, 86, 87(fn.9), 114

Fella (Fellanga): 64(fn.60), 70

Fenikang: 75(fn.2)

Fentress, Elizabeth: 52

Ferti: 20

Fertit: 27, 27(fn.55), 30

Fez: 62(fn.36)

Fezzan (Fazzan): 63(fn.47), 73, 74, 119

Fiki Khalil: 54

Fiki Muhammad Tahir: 62(fn.38)

Fileil, Sultan: 30

Filga: 59, 94, 95

Fir: 27(fn.55)

Fira: 64(fn.53)

Firat: 27(fn.55)

Fisher, AGB: 111(fn.11), 112, 112(fn.26)

Fora: 51

Forang Aba: 71

Foranga Fur: 71

Forei: 95

Foucauld, Pére: 13

France, French: 13, 30, 30(fn.78), 34(fn.29), 48(fn.51), 63(fn.47), 65(fn.67), 73(fn.146)

Franciscans: 137

Frobenius, Leo: 135

Fuchs, P.: 72(fn.128)

Fugbu (Fugobo): 80(fn.3)

Fulani: 36(fn.44), 72, 119

Funj: 24(fns.21, 25), 25, 31(fn.4), 38, 38(fn.57), 51, 87, 88(fn.18), 89, 95, 112, 126, 128(fn.60), 129, 131

Funj Chronicle: 51, 126, 126(fn.44), 127, 131

Fur: 6-7, 11, 16, 17, 18, 27(fn.55), 28, 29(fn.71), 30, 31, 33, 34, 34(fn.25), 36, 45, 45(fn.18), 51, 53, 55, 57, 57(fn.2), 62, 64, 64(fns.53,54), 71, 71(fns.120,123), 75, 78(fn.14), 79, 86-109, 86(fn.7), 91(fn.5), 123, 139

Fur King-Lists: 97-109

Fur Language: 86, 86(fn.2), 94(fn.22)

Furnung Hills: 60, 60(fn.23), 119(fn.38)

Furogé (Feroge): 27, 27(fn.55), 29(fn.73), 30

G

Ga’afir Gurmun (Germun), King: 85

Gabir: 64

Gabri: 20

Gaéda: 44, 44(fn.15)

Gamburu: 69(fn.101), 72-73

Gami Kheir, Malik: 116(fn.1), 118

Gao: 110(fn.1)

Gaoga: 33, 110-112, 110(fn.1), 112(fns.21,24,26)

Garamentes: 115, 130

Garoumélé: 73, 73(fn.143)

Garu: 72(fn.135)

Gedaref: 50

Garstang, John: 62

Gath: 128

Gaya: 136(fn.32)

Gaza: 128

Gelti al-Naga: 130(fn.94)

Genealogy: 5, 11(fn.11), 12-15, 24, 47(fn.46), 53(fn.91), 84, 96(fn.41), 97, 111(fn.12), 128(fn.68)

Geneina: 86

Genies (Jinn): 62(fn.38)

German: 64(fn.57)

Gezira: 129(fn.78)

Ghabashat, Battle of: 89

Ghana: 22, 135

Gharbanin: 25(fn.29)

Ghazali: 67, 134

Ghudiyat Arabs: 87

Ghulam Allah ibn ‘Ayd: 28(fn.65)

Ghumsa: 46

Ghuzz: 74

Giants: 31(fn.4), 53-54, 73, 74, 123, 128, 128(fn.68)

Giggeri, Sultan: 88, 95

Gilgamesh: 37, 37(fn.50)

Gili: 78

Gillan, Angus: 7, 35, 35(fn.34)

Gillif Hills: 125

Gillo: 75

Ginsi: 87

Gitar, King: 28

Gitxsan: 15

Glass: 65-66, 65(fn.67)

Gnol: 23(fn.15)

Gobir: 135

Gog and Magog: 36, 36(fn.44)

Gogorma: 95

Gold: 71

Gordon-Alexander, LD: 96(fn.40)

Goths: 36(fn.44)

Greece, Greek: 7, 28(fn.65), 37, 38, 65(fn.67), 126(fn.44), 132, 135(fn.25), 137

Gros, René: 29, 44(fn.17)

Guanche: 130(fn.93)

Gula: 27(fn.55)

Gule: 128(fn.60)

Gunda: 47(fn.46)

Gura’an (Kura’an): 25, 34(fn.29), 56, 132, 137, 137(fn.37)

Gurli (Gerli): 95

Gurri: 95

Gurzil: 37(fn.53)

H

Haaland, R.: 114

Hababa, Habuba’at: 62(fn.38), 97

Habasha: 22, 23, 33(fn.22)

Hache à gorge axe: 125

Haddad: 113

Hafir: 120, 125, 125(fn.37), 130

Hajang Keingwo: 97, 97(fn.46)

Hajar Kudjuna: 25

Hajar Kujunung: 30,

Hajar Te’us: 28(fn.65)

Hajj ‘Ali: 50

Hajj Brahim Delil: 63

Ham, Hamites: 6-7, 8, 22, 25, 26, 38, 46, 125(fn.33), 128

Hamad ‘Abbas Himyar: 29(fn.73)

Hamaj (Hamej): 128, 128(fn.60)

Hamid bin Abdullah: 96(fn.41)

Hamid Ahmad: 28(fn.64)

Hammad bin Tamr: 119

Harim: 57(fn.2), 62(fn.42)

Harkhuf: 45(fn.21), 116

Harkilla: 135

Harut: 78

Hassaballah, General: 126

Al-Hassar, Sultan: 44

Hausa: 44, 70, 73(fn.143)

Hauya Hoe: 59, 113, 119

Hawara Berbers: 125, 125(fn.33)

Hawawir: 125, 125(fn.33),

Haycock, BG: 113

Haydaran, Battle of: 52

Haykal: 68

Hebrew, Hebrews: 36(fn.44), 128

Hebron: 65, 128

Helbou: 27(fn.31)

Helmolt, Dr.: 77(fn.9)

Henderson, KDD: 29

Henige, DP: 14, 84

Heracles: 37(fn.50)

Heraclius: 135

Herodotus: 11

Al-Hidjr: 28(fn.65)

Hijaz: 27(fn.53), 27(fn.54), 28(fn.65), 49, 78, 136

Hill, LG: 25

Hill Nubian: 120

Himyarites: 18, 26, 26(fns.38, 39), 29(fn.73), 38, 39, 38(fn.61), 49, 111(fn.12), 125(fn.33), 135, 136

Hobbs, Capt. HFC: 35, 35(fn.34)

Hobson, RL: 70

Hoes (see also Hauya hoes): 122, 122(fn.6)

Hoggar Mountains: 13, 20(fn.22),

Holt, PM: 48(fn.53), 51, 51(fn.74), 98

Holy Stones (see Stone Worship)

Houghton, AA: 65, 65(fn.61), 66(fns.74,75), 67(fn.87), 68, 69(fn.100)

Howara: 119

Hrbek, I: 63(fn.47), 71(fn.1244), 112

Huard, P.: 113, 132(fn.7), 134

Huddleston, Major HJ: 35

Hudud al-Alam: 132-134

Human Sacrifice: 78

Hummay, Sultan: 111(fn.12)

Hungarians: 74

Huns: 36(fn.44)

Hurreiz, Sayyid Hamed: 54

Husayn (Hussein) Abu Koda: 78(fn.14)

Husayn Morfaien, Sultan: 30

I

Ibadites: 137

Ibn ‘Abd al-Zahr: 129

Ibn Abi Zar of Fez: 125(fn.33)

Ibn al-‘Arabi: 23

Ibn Assafarani: 130,

Ibn Batuta: 64(fn.53)

Ibn Hazm: 38

Ibn Kathir: 37

Ibn Khaldun: 23, 38, 52, 52(fn.78)

Ibn Qutayba: 6

Ibn Sa’id: 22, 23, 37, 136

Ibn Selim al-Aswani: 37(fn.46), 62(fn.36), 126(fn.44), 127, 129(fn.78)

Ibn Shaddad: 52

Ibn al-Wardi: 33(fn.22)

Ibrahim (Pretender to the Fur Throne): 78(fn.14)

Ibrahim, Sultan (Fur): 5, 62(fn.38), 96, 116

Ibrahim, Sultan (Tunjur):

Ibrahim al-Dalil (see Dali)

Ibrahim Musa Muhammad: 7, 9, 9(fn.9), 68(fn.88), 70(fn.111)

Ibrahim bin ‘Uthman, Sultan: 110

Idris Aloma, Mai: 70, 70(fn.111), 71, 72-73, 75(fn.3), 123

Idris Ja’l: 87

Idris Katargarmabe (Katarkanabi), Sultan: 112

Al-Idrisi, Muhammad: 17, 22, 33, 45(fn.25), 111, 112(fn.20), 137

Ifriqsun bin Tubba Dhu al-Manar: 38

Ihaggaren Tuareg: 13

Illo: 136

Imam Ahmad: 47

Imatong Hills: 33(fn.12)

India, Indian: 63, 63(fn.47)

Iriba Plateau: 77,

Irima: 64(fn.53)

Iron, Iron-working: 33, 59(fn.13), 62, 70, 93, 113-115, 114(fns.12,16), 119-120, 120(fn.43), 122, 123, 123(fn.16), 140

Irtet: 116

Irtt: 116,

Isabatan: 13

‘Isawi bin Janqal: 89

Islam, Islamization: 11, 12, 18, 28(fn.65), 34, 36(fn.44), 44, 48, 50, 53(fn.90), 55, 62(fn.38), 69, 70-71, 71(fn.124), 72(fn.128), 73, 86-87, 86(fn.7), 89, 95, 97, 110, 111(fn.12), 112, 117, 117(fn.14), 118, 127, 135-136, 139

Isma’il Ayyub Pasha: 75(fn.7), 103-104

Israel: 128

Italy, Italians: 34(fn.29), 54, 63(fn.47),65(fn.67), 110(fn.1)

Iya Basi: 78(fn.14)

J

Ja’aliin Arabs: 25, 26(fn.39), 28(fn.65), 45, 119

Jackson, HC: 124, 124(fn.32), 125(fn.37)

Jacobites: 137

Jallaba Hawawir: 125(fn.33)

Jalut: 13(fn.25

Janakhira: 27(fn.55)

Janqal (Jongol), Sultan: 88, 88(fn.18)

Japheth: 36(fn.44)

Jarma: 56

Jawami’a: 96-97, 96(fn.41), 129

Jayli: 51

Jebel ‘Abd al-Hadi – see Jebel Haraza

Jebel Adadi: 95, 95(fn.31)

Jebel Afara: 96(fn.38)

Jebel Aress: 48

Jebel Au: 18

Jebel al-Azib: 129

Jebel Bayt al-Nahas: 129

Jebel Belbeldi: 130(fn.94)

Jebel Burgu: 28(fn.65)

Jebel Doba: 31

Jebel Eisa: 60, 118

Jebel Ferti: 59

Jebel Foga: 21, 91, 91(fn.3), 93, 95

Jebel Forei: 93

Jebel Gelli: 50(fn.63)

Jebel Gidera: 36(fn.41)

Jebel Gurgi: 54

Jebel Haraza: 33, 123, 123(fn.12), 129, 129, 129(fn.77), 130-131, 130(fns.87,94), 131

Jebel Hileila: 33,

Jebel al-Hosh: 125

Jebel Hurayz (Harayz, Hereiz): 43, 48-9

Jebel Irau: 126

Jebel Jung: 64(fn.53)

Jebel Kaboija: 117

Jebel Kadama: 45

Jebel Kadjanan: 30

Jebel Kadjano: 25

Jebel Kajanan: 30

Jebel Karshul: 130

Jebel Katul: 129

Jebel Keima: 16, 31(fn.6), 93

Jebel Kerbi: 60

Jebel Kilwa: 28, 30, 31, 33

Jebel Kurkeila: 130

Jebel Kwon: 135

Jebel Liguri: 23

Jebel Mailo: 53

Jebel Maman: 127(fn.58)

Jebel Marra: 1, 7, 9, 16, 17, 20, 21, 25, 27(fn.55), 28, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.66), 31, 33, 34, 36, 36(fn.41), 38, 45, 51, 53, 54, 57(fn.5), 62(fn.42), 66, 78(fn.14), 86, 87-90, 91, 93-95, 94(fn.21), 112, 119(fn.38), 128, 131, 139

Jebel Masa: 59, 72(fn.129)

Jebel Meidob – See Meidob Hills

Jebel Mogran: 117

Jebel Mojalla: 95

Jebel Moya: 130

Jebel Mun: 79

Jebel Mutarrak (Mutarrig): 59-60

Jebel Nami: 54, 94, 95, 97,

Jebel Omori: 113(fn.1)

Jebel Otash: 36

Jebel al-Raqta: 125

Jebel Shalasi: 130

Jebel Si: 16, 20, 53, 54(fn.100), 57, 57(fn.5), 75, 75(fn.3), 86

Jebel Siab: 118

Jebel Silga: 33

Jebel Suruj: 88(fn.18)

Jebel Tageru: 125, 128-129

Jebel Taqali: 50, 50(fn.64)

Jebel Teiga: 60, 122(fn.6)

Jebel Tika: 95

Jebel Tréya (J. Thurraya): 77-78

Jebel Udru: 117

Jebel Um Kardos: 30, 53(fn.98)

Jebel Umm Qubu: 125

Jebel Wara: 33

Jebel Zankor – See Zankor

Jebel Zureiq: 21

Jebelein: 31(fn.4)

Jebelawi (Jebala, Jebelowi) Fur: 86, 87, 89

Jerash: 65, 65(fn.67)

Jernudd, B: 86

Jesus Christ (Nabi Isa): 136

Jews, Judaism: 15, 26(fn.38), 115, 136, 137

Jil Shikomeni: 111

Jinn-s: 79, 117

Joshua: 128

Juba II: 110(fn.3)

Juhayna Arabs: 129

Jukun: 26, 27, 135

Jungraithmayr, H.: 25, 29(fn.67)

Jupiter Ammon: 37(fn.54)

Jur: 23(fn.15)

Jura: 124

K

Kababish Arabs: 130(fn.96)

Kabbashi: 28

Kabkabiya: 28(fn.65), 88, 90

Kabushiya: 37(fn.46), 129(fn.78)

Kachifor, Sultan: 30

Kadama: 43, 55, 77, 77(fn.6)

Kaderu: 129(fn.78)

Kadmul: 47(fn.45), 48

Kadugli: 23, 23(fn.15), 75

Kagiddi – see Shelkota

Kai: 47

Kaiga: 112

Kaitinga: 25, 29(fn.71)

Kaga: 117

Kaja: 116(fn.4), 117

Kaja Seruj: 122, 123, 127

Kajawi: 123

Kalak Tanjak: 78

Kalamsiya: 38, 38(fn.60)

Kalck, Pierre: 112, 112(fn.26)

Kalga: 34

Kalge: 87(fn.9)

Kalokitting: 66(fn.76)

Kamadugu: 72

Kamal Yunis: 68(fn.88), 69(fn.101)

Kamala Keira: 97

Kamdirto: 119(fn.37)

Kamni: 96(fn.44)

Kamteinyi, Sultan: 28, 33

Kanem: 7, 12, 16, 22, 23, 26, 26(fn.39), 33, 44, 44(fn.8), 44(fn.13), 45, 46, 46(fn.27), 47, 47(fn.46), 48, 53, 56, 62, 63, 63(fn.47), 67(fn.86), 70, 72, 72(fn.130), 73(fn.143), 74, 80, 80(fn.1), 81, 84, 85, 111, 111(fns.11,12), 112, 118, 118(fn.24), 120, 122(fn.6), 128, 135, 136

Kanembu: 44, 44(fn.8), 46, 74, 80(fn.3), 111, 111(fns.11,12), 112, 119-120

Kano: 63, 77(fn.1)

Kanuri: 11, 16, 22(fn.4), 23, 28(fn.65), 44, 44(fn.13), 45, 46, 47, 47(fn.43), 54, 61(fn.33), 72(fn.135), 73(fn.142), 111, 111(fns.11,12), 112, 119, 128, 136

Kapteijns, Lidwien: 27

Kara: 27(fn.55)

Karakit Fur: 7, 86, 86(fn.4)

Karanga: 45, 77

Karanog: 124(fn.25)

Karkour-Nourène Massif: 44

Kas (Kusayr), King: 85

Kashemereh: 77

Kashémerém: 43

Kashmara: 25, 77

Kassala: 50, 52, 127(fn.58), 129(fn.78)

Kassifurogé, King: 30, 53(fn.98)

Katsina: 137

Kauara (Kawra) Pass: 20-21, 57

Kawar: 16, 22, 33, 45, 45(fn.25), 45(fn.25), 46, 46(fn.26), 47, 47(fn.46), 54, 120, 136

Kawka: 22

Kayra Fur: 10, 11, 11(fn.11), 12, 17, 18, 24, 29(fn.66), 31, 34(fn.25), 38, 43, 43(fn.3), 49, 50, 51, 55(fn.111), 59, 59(fn.15), 63, 64, 66, 69, 70, 75, 75(fn.3), 84-85, 86-109, 88(fn.21), 91(fn.2), 97(fn.45), 112, 120(fn.46), 131, 139-140

Kebeleh: 18-20, 18(fn.17)

Kedir, King: 27. 28

Kedrou: 129, 129(fn.78)

Kel Innek: 130

Kel Rela: 14, 14(fn.29)

Kella: 14

Kenen (Khanem), King: 85

Kenzi-Dongola: 120

Kerakirit: 75(fn.3)

Kerne: 78

Kerker: 60, 60(fn.18), 65, 118, 119-120, 122(fn.6)

Kerkur: 118(fn.27)

Kernak Wells: 125

Al-Kerri: 75, 75(fn.3), 126

Kersah: 129, 129(fn.78)

Khalaf, Sultan: 29, 29(fn.71), 30

Khamis Mubaju: 31(fn.9)

Kharadjites: 137

Khartoum: 8,

Khazars: 36(fn.44)

Kheir Ullah: 43

Khor Gadein: 123, 130

Khor al-Sidr: 125

Khouz: 73, 74, 128(fn.68)

Khujali bin ‘Abd al-Rahman, Faki: 88

Khuzam Arabs: 72(fn.128)

Khuzaym (Khoués), King: 85

Kilwa: 10

Kinin (see also Tuareg): 34(fn.29), 128

Kira: 47

Kirati (Kurata) Tunjur: 44, 47

Kirsch, JHI: 77

Kisra: 135, 135(fn.25)

Kitab Dali – see Law, Pre-Islamic

Knoblecher, Ignaz: 51(fn.74)

Kobbé: 4, 5

Kobbé Zaghawa: 88

Kobe: 94

Koc Col: 75

Kodoï: 45

Koenig, Dr A-M.: 29(fn.66), 30(fn.78), 88(fn.18), 100

Kolge: 88, 94(fn.21)

Koman: 128(fn.60)

Konda (Kidney feast): 97

Konnoso: 8

Konyunga Fur: 34(fn.25)

Kor, King: 29, 29(fn.66), 51

Kora (Korakwa): 7, 75(fn.3), 86(fn.4)

Kora Mountains: 54

Koran: 36(fn.44), 37, 50, 73, 89, 97

Kordofan: 23, 24, 24(fn.25), 25, 27, 27(fn.55), 28, 28(fn.58), 28(fn.65), 30(fn.78), 34, 49, 50, 50(fn.60), 50(fn.64), 52, 53, 64(fn.54), 66(fn.75), 70, 75, 82, 85, 87-90, 87(fn.9), 96(fn.41), 101, 110, 114(fn.12), 116(fn.4), 117, 117(fn.10), 118(fn.19), 119-120, 120(fns.46,48), 122, 123, 123(fn.12), 124-125, 125(fn.33), 127-131, 129(fn.86), 130(fn.96), 132, 135

Korkurma (Korgorma): 94(fn.21)

Koro Toro: 113, 132, 132(fns.5,7), 134-135, 134(fn.14), 140

Koro Toro Radiocarbon Dates: 138

Koseru (Kaseru), Sultan: 33

Kotoko: 63, 111(fn.11)

Kotor-Furi: 47(fn.46)

Kourdé: 77

Kreish: 8

Kropácek, L: 53, 72, 123

Kufic: 46(fn.37)

Kufra (Koufra): 4, 22, 26(fn.39), 31(fn.5), 77

Kujunung: 28

Kuka: 33, 59, 111-12, 111(fn.11)

Kuli (Kulli): 86, 88

Kulu: 64

Kulubnarti: 38

Kundanga: 78(fn.14)

Kunjara Fur: 45(fn.18), 62, 75(fn.7), 85, 86, 89-90, 97, 139

Kurds: 74

Kuroma, King: 51

Kurra: 59(fn.9)

Kurru: 47, 68, 123, 123(fns.15,16), 127

Kuru (Kurru), King: 28(fn.64), 31, 43, 84, 87, 93, 93(fn.10), 139

Kusbur (Kosber), King: 16, 28, 29, 31

Kush (Cush): 22, 23, 47, 113, 116(fn.4), 119, 123(fn.16), 127

Kush al-Wagilah (Kushah, Kus): 123

Kusi: 59

Kuttum: 9, 29(fn.71), 43, 54(fn.100), 119(fn.38)

Kutul: 117

Kwawang, Kunijwok: 75

L

Lagowa: 24

Lake Chad: 5, 26, 28(fn.65), 31(fn.5), 72(fn.129), 74, 111(fn.9), 114, 130, 132

Lake Esan: 35

Lake Fitri: 33, 45, 55(fn.111), 56, 110, 111, 111(fn.9), 111(fn.11), 112

Lampen, GD: 117

Lamtuna: 137

Lange, D: 73(fn.142), 110

Lango: 33(fn.12)

Largeau, Colonel: 6(fn.6), 73(fn.146)

Larymore, Constance: 136

Last, Murray: 22

Law, Islamic: 71, 71(fn.118,123)

Law, Pre-Islamic: 71, 71(fns.118,121)

Le Rouvreur, Albert: 36(fn.41)

Lebeuf, JP: 74, 77

Lemba: 15

Leo Africanus: 33, 110-112, 112(fns.20,21,25), 113, 137

Leucaethiopes: 16

Lewicki, T.: 22

Al-Libei, Sultan: 44

Libya, Libyans: 17, 34(fn.29), 37, 37(fn.53), 97

Libyan Desert: 117

Liguri: 23, 24

Litham: 43(fn.3), 45, 45(fn.25), 64(fn.53), 96(fn.44)

Locust Wizards: 34(fn.25)

Lol: 23(fn.15)

Lotuko: 33(fn.12)

Low, Victor: 12, 24,

Luniya Mountains: 136-137

Luwai ibn Ghalib: 26(fn.39)

Luxor: 38

Lwel: 75

M

Ma’at: 38

Maba: 44, 45, 74, 77(fn.9)

Mabo: 118(fn.28)

Macedonians: 37(fn.51)

Machina: 72

MacIntosh, EH: 27(fn.54), 30, 31,

MacMichael, Harold A.: 5, 12, 16, 22, 24, 27, 29(fn.71), 38(fn.57), 43, 43(fn.6), 49, 49(fns.55, 58), 52(fn.86), 53, 57(fn.5), 60, 62(fn.38), 64(fns.53,54,60), 65, 65(fn.61), 66, 66(fn.75), 67, 68, 70, 72(fn.129), 78(fn.14), 79, 85, 86, 96(fn.40), 116, 117, 120(fn.46), 128, 129(fns.77,86), 130, 130(fn.87)

Mace-heads: 130(fn.87)

Madala: 55

Madeyq: 68(fn.97)

Madi: 33(fn.12)

Magharba: 62, 62(fn.36), 63(fn.47), 70(fn.111)

Maghreb, (Maghrab, Maghrib): 20, 26(fn.38), 38, 39, 52, 62, 62(fn.36), 125(fn.33)

Magumi (Magomi: 16, 111, 111(fns.11,12)

Magyars: 36(fn.44)

Mahamid Arabs: 45, 89

Mahas: 117

Mahdiyya: 11(fn.10), 28, 36(fn.39), 87, 96, 116,

Mahmud al-Samarkandi: 24(fn.25)

Mahram: 16(fn.7)

Mai, King: 28

Mak Husayn: 38

Maiduguri: 74

Mailo Fugo Jurto: 30(fn.74),

Majala: 94

Majians: 128(fn.68)

Makada: 48

Makuria: 123, 140

Malakal: 31(fn.4)

Maledinga: 134

Malha City: 118, 119-120

Malha Crater: 116, 116(fn.1), 118, 118(fn.20), 119-120

Mali: 5, 115, 135

Malik al-Dubban: 97

Malik Kissinga Dora: 97

Malikite Mandab: 71, 71(fn.118)

Al-Mallagi: 125

Malumba: 136(fn.32)

Malwal: 23(fn.15)

Mamluks: 5, 62(fn.36), 129

Manawashi, Battle of: 62(fn.38), 96

Al-Mandar: 95

Mandara: 23, 46, 54, 63, 135-136, 136(fn.32)

Mandara Chronicle: 136, 137

Manjil: 38, 38(fn.57)

Al-Mansur Qala’un, Sultan: 52

Mao: 44, 45, 67(fn.86), 114, 118, 118(fn.24), 119-120, 119(fns.36,42), 120

Maqdum: 36, 36(fn.41)

Al-Maqrizi (Makrizi): 23, 126(fn.44)

Maranda: 22

Marawiyyun: 22

Ma’rib: 26(fn.38), 52(fn.78)

Masalit: 25, 43(fn.3), 64, 78(fn.14), 87

Masmaj: 55

Al-Mas’udi: 39

Matrilineal Succession: 46, 55, 56, 116, 118, 130, 130(fn.93)

Mauny, R: 112(fn.26), 134

Maydon, Major: 117

Mayram: 61(fn.33)

Mayri: 51

Mayringa Fur: 51

McCall, DF: 135, 135(fn.25)

Mecca: 28, 55, 62(fn.42), 71(fn.124), 72, 87, 136

Medes: 37(fn.52)

Meidob Hills, Meidobis: 18, 33(fn.18), 60, 60(fn.18), 116-121, 116(fn.4), 119(fn.38), 120(fns.46,48), 121, 122(fn.6), 128

Meidobi Burial Customs: 117(fn.11)

Meidobi King-Lists: 121

Meidobi Religion: 117-118, 117(fn.14)

Meidobi Sections: 116

Melik – see Malik

Memmi: 63

Merbo: 9

Merga: 46

Meroë, Meroitic: 8, 25, 26, 31, 31(fn.4), 46, 48, 54, 62, 112(fn.21), 113-115, 113(fn.1), 119, 122, 122(fn.6), 123, 124, 124(fn.29), 125, 127, 127(fns.51,56), 130, 132, 134-135, 140

Merri: 35, 36, 36(fn.45)

Michelmore, APG: 72(fn.129)

Missirya (Messiriya) Arabs: 50(fn.61), 72(fn.128)

Mihrab: 61, 66, 68-69

Mima (Mimi): 8, 25, 45, 55, 64, 64(fns.53,54)

Minbar: 68

Minos: 38(fn.58)

Mira: 50

Miri: 33

Misr Muhammad: 49(fn.59)

Mitnet al-Jawwala: 125

Moab: 128

Mockler-Ferryman, Major: 136

Modat, Captain: 112

El-Moghraby, Asim I.: 60(fn.18), 118-120,

Molu: 86, 87(fn.9)

Morocco: 14(fn.29)

Mohammed, Ibrahim Musa: 17, 69, 69(fn.101), 91(fn.5), 96(fn.40), 113, 120(fn.44)

Mondo: 44(fn.8), 80(fn.1), 81, 84, 85

Mongo-Sila: 23, 24

Mongols: 36(fn.44), 50

Morga: 63

Moro: 31(fn.5), 33(fn.12)

Moses: 37, 37(fn.51)

Muglad: 29

Al-Muhallabi: 22, 22(fn.4)

Muhamid Arabs: 55

Muhammad (Daju King): 29

Muhammad (Prophet): 28(fn.65), 71(fn.124), 110, 136

Muhammad ‘Ali: 30(fn.78), 62(fn.36), 73

Muhammad Bakhit, Sultan: 30

Muhammad Bello, Sultan: 36(fn.44)

Muhammad Bulad, Sultan: 27

Muhammad Bulat, Sultan: 88

Muhammad Dawra, Sultan: 88-89, 88(fn.23), 95-96

Muhammad Fadl, Sultan: 96

Muhammad Gunkul, Sultan (see Janqal)

Muhammad al-Hasin, Sultan: 49

Muhammad Husayn, Sultan: 95-96

Muhammad Ibrahim: 52(fn.77),

Muhammad Idris bin Katarkamabe, Mai: 70

Muhammad al-Ja’ali: 50(fn.64)

Muhammad Sayah: 118

Muhammad al-Shayb, Sultan: 44

Muhammad al-Shinqiti: 78(fn.15)

Muhammad bin Tamr: 119

Muhammad Tayrab, Sultan: 55(fn.111), 64(fn.54), 75(fn.3), 89-90, 95, 96, 97, 120(fn.46)

Muhammad Wad Tom, Shaykh: 129(fn.75)

Muhammad Yanbar: 119, 119(fn.36)

Al-Mu’izz ibn Badis: 52

Mujuf: 55

Mukarra (Mukurru): 37(fn.46), 46, 46(fn.31), 46(fn.35), 47, 47(fn.46), 52, 56, 127, 134

Mundara: 130

Munio: 46, 54

Al-Mur, Sultan: 55(fn.111)

Murdock, George Peter: 13

Murgi: 64(fn.54)

Murra: 95

Murtafal: 31(fn.6)

Murtal: 97

Musa, Sultan: 88, 94, 94(fn.21), 96, 96(fn.39)

Musa ‘Anqarib: 88-89

Musa Tanjar: 45, 45(fn.18)

Musa Um Ruddus, Shartai: 54(fn.100)

Musaba’at: 30(fn.78), 33, 49, 84-85, 84(fn.3), 85, 87-89, 97, 101, 103, 123, 131

Mustafa, Sultan: 24

Musulat: 63

Mutansir: 52, 52(fn.79)

Muwalih: 125

Muweileh: 125

N

Nachtigal, Gustav: 5, 13, 28, 28(fn.65), 31, 34, 44, 44(fn.8), 44(fn.13), 47, 47(fn.43), 49, 50, 53, 53(fn.91), 54, 55(fn.111), 57(fn.2), 57(fn.5), 71, 71(fn.121), 73, 75(fn.3), 75(fn.7), 77, 78(fns.14-15), 80(fn.1), 87(fn.9), 88, 91, 96, 102, 111, 118, 120(fn.46), 131

Nafer, King: 29

Nahas: 62, 62(fn.38), 87, 118

Na-Madu, King: 118-119

Nanku: 64(fn.53)

Napata: 26, 113, 127

Nari: 33

Nas Far’aon: 27, 27(fn.54)

Nassara (Nazarene): 73, 132, 140

Negib Effendi Yunis, Yuzbashi: 118(fn.19)

Nejran: 136

Newbold, D: 16, 61(fn.31), 117, 122, 122(fn.2), 123, 123(fn.13), 124, 124(fn.29), 125, 127(fn.57), 129, 129(fns.74,86), 130(fns.92,94)

N’Gazargamu: 72-73

Ngok Dinka: 23

Nguru: 73

Niamaton: 79

Nieke, Margaret R.: 11

Niger: 115

Niger (River): 110(fns.1,3), 136

Nigeria: 7, 13, 27, 44, 113, 114, 132, 136(fn.32)

Nikki: 136

Nilo-Saharan Language Group: 86

Nisba: 54

Njamena: 23

Nkole: 14

Noah: 28(fn.65), 128

Nobatia: 38

Nobiin: 120

Nok Culture: 114

Northern Rhodesia: 13

Noyo: 94

Nuba: 22, 23, 27(fn.55), 33, 33(fn.22), 50, 117, 118(fn.19), 122, 128-130, 136

Nuba Hills: 27, 120, 128

Nubia, Nubians: 11, 38, 43, 43(fn.6), 44(fn.13), 46, 46(fn.31), 46(fn.37), 47, 50, 52, 52(fn.86), 56, 64(fn.54), 65, 66, 67(fn.86), 68-69, 69(fn.102), 74, 97, 110, 112, 112(fn.21), 116-117, 118, 120(fn.48), 122-123, 123(fn.16), 124(fn.29), 126(fn.44), 129, 130-131, 132, 132(fns.6,7), 134-135, 137(fn.37), 139-140

Nubian Language: 116(fn.4), 120, 130(fn.92), 131

Nuer: 34(fn.26)

Nuh: 22

Nukheila: 22(fn.1), 127(fn.57)

Numan Fedda: 97(fn.45)

Nupe: 135

Nur Angara: 62(fn.38)

Nuri: 123(fn.16)

Nuwabiya: 123

Al-Nuwayri: 52

Nyala: 23, 24, 27, 27(fn.52), 28, 62, 62(fn.38), 75, 86

Nyèri: 45

Nyidor, Reth: 75

Nyikango: 75, 75(fn.5)

Nyolge (Nyalgulgule): 23, 23(fns.15, 19), 24, 29

O

Al-Obeid: 75, 88(fn.18)

O’Fahey, RS: 46(fn.31), 50, 56, 61(fn.33), 64(fn.57), 112, 112(fn.25)

Ogot, Bethwell A: 134-135

Ogra: 64

Olderogge, DA: 6

Omar Kissifurogé – see ‘Umar Kissifurogé

Omdurman: 62(fn.38), 116, 117

Oral Tradition: 10-15, 31(fn.6), 51(fn.69), 74, 75-76, 113, 129, 135, 139-140

Órre Baya: 57, 57(fn.2), 60, 95

Órre De: 57(fn.2), 60

Osiris: 8(fn.15)

Ostrich Eggs (decorative): 34, 34(fn.26), 36

Ottomans: 5, 24(fn.25), 74

Ounianga: 77

Ouogayi: 73(fn.148)

Oxyrinchus: 43(fn.6)

P

Paçir: 75, 75(fn.3)

Pahlavi: 135(fn.25)

Palestine: 65, 68, 128, 128(fn.68)

Palmer, HR: 7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 33, 46(fn.32), 48, 53(fn.90), 55, 72, 80(fn.1), 112, 112(fn.20), 128, 129, 135, 136, 137

Papadopoullos, T.: 135

Papyrus: 116(fn.1)

Parthians: 26(fn.38), 36(fn.44)

Patwac: 75

Pelpelle: 89

Penn, AED: 122-123, 122(fn.7), 126-127

Perari Kalga: 34

Perron, Dr.: 5

Persia, Persians: 26(fn.38), 37, 37(fn.52), 132, 134-135, 135(fns.21,25)

Petherick, J.: 52

Petracek, Karel: 119(fn.34)

Philae: 8, 33

Phoenicians: 115

Pilgrim Bottles: 124, 124(fn.29), 125, 127, 129, 129(fn.75)

“Platform of Audience”: 60, 61, 62, 65, 119

Pleiades: 78(fn.13),

Pliny the Elder: 16, 110(fn.3)

Pomponious Mela: 16

Pontiphar: 49(fn.58)

Potagos, Panyotis: 23

Pottery: 70, 122(fn.7), 123, 124, 124(fn.32), 132, 132(fn.5), 134, 134(fn.13), 140

Pre-Islamic Religion: 34, 86-87, 87(fn.9), 96(fn.38), 97, 117-119, 117(fn.14), 123, 136, 137

Prisons: 66, 66(fn.76), 93

Prophecy: 35

Ptolemy, Ptolemies, Ptolemaic Period: 16, 38, 43(fn.6), 127

Q

Qalaun, Sultan: 129

Al-Qalqashandi: 111(fn.12)

Qaqu: 22

Qarri (Querri, Gerri): 122, 125-127, 126(fn.44), 127(fn.46), 131

Qayrawan: 52, 125(fn.33)

Qays ‘Aylan: 38

Qelti al-Adusa: 129, 129(fn.73)

Qibla: 95

Qihayf, Battle of: 89

Qimr: 36(fn.43), 88

Qubba-s: 36(fn.41), 69, 95, 96

Quran – see Koran

Quraysh: 26(fn.39), 50, 50(fn.64), 102, 111(fn.12)

R

Radcliffe-Brown, AR: 7-8

Al-Rahad: 50

Rahaman: 26(fn.38)

Red Sea: 38, 63(fn.47)

Redjem: 118(fn.27)

Reisner, George A: 123

Reth: 75, 75(fn.2)

Reygasse, Maurice: 13-14, 20(fn.21), 118(fn.27)

Richards, Audrey I: 13

Rifa’a: 51

Rikabiya Ashraf: 130

Rizayqat Arabs: 89

Rizik (Rézik), King: 85

Ro-Kuri Region: 53, 95

Robinson, AE: 28, 29(fn.66), 38(fn.58)

Rodd, Francis R.: 130

Rome, Romans: 14, 26(fn.38), 37, 37(fn.52), 74, 114, 135, 137

Ronya: 59

Rosen, Georg: 77(fn.9)

Royal Platform: 59

Royna: 59(fn.12)

Rugman, Lady: 66-67

Rwanda: 115

Ryan, Bimbashi: 124(fn.32)

S

Sa’ad, Sultan: 44

Sabaloka Gorge: 126

Sabula: 57

Sabun: 75(fn.7), 91

Saccae: 63

Sadaqah: 97

Safia: 130

Sagava: 63

Saifawa Mai-s: 71

Salah, Sultan: 29

Salf (Zalf), King: 30

Salih (prophet): 28, 28(fn.65)

Salih ibn ‘Abdallah ibn ‘Abbas: 28(fn.65),

Salt Collection, Salt Trade: 116, 118, 120

Salt, Sir Henry: 86(fn.2)

Salua: 94

Al-Samarkandi: 50

Samarra: 65(fn.67)

Sambei: 27, 34(fn.25)

Sambella (Sambellanga): 64(fn.60)

Sania Kiri: 57

Samna: 33

San’a: 15

Sanam: 123(fn.16)

Sandstone Rings: 129–130, 130(fn.87)

Sanhaj Berbers (Sanhaja): 48, 125(fn.33), 128, 128(fn.68)

Sania: 123

Santandrea, P. Stefano: 29(fn.73)

Sanussis: 34(fn.29), 73, 73(fn.146), 74, 128(fn.68)

Sao: 31(fn.5), 63, 72, 111(fn.11)

Sarsfield-Hall, EG: 87, 117(fn.14)

Sassanids, Sassanians: 26(fn.38), 135

Sau: 55

Sa’ud: 28(fn.65)

Savonnier: 80(fn.2)

Sawwar bin Wa’il bin Himyar: 125(fn.33)

Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan: 26(fn.38), 111(fn.12)

Sayfawa: 16(fn.7), 111, 111(fns.11,12)

Schmidt, Peter R: 14

Scythians: 36(fn.44)

Sebakh, King: 129

Selatia: 62(fn.38)

Seleukos I Nikator: 37(fn.51)

Seligman, CG: 6, 7, 75(fn.2), 130(fn.87)

Selima Oasis: 46, 46(fn.37), 134

Seliquer, Captain: 132

Sendi Suttera, Iya Basi: 89

Serbung Masalit: 87

Serengiti: 60(fn.18), 118, 119

Sergitti: 79

Serra East: 68(fn.97)

Serra West: 67

Shabaka, King: 129(fn.79)

Shadow Sultan (see Kamni)

Shaffai Boggarmi, Dardai: 48(fn.51)

Shaheinab: 8

Shari’a – See Law, Islamic

Shartai: 34(fn.25)

Shatt: 23, 23(fn.15), 24, 29

Shau al-Dorsid, Sultan: 16, 27, 30, 30(fn.74), 44(fn.15), 48, 50, 51, 53-54, 56, 57-64, 57(fn.5), 59(fn.15), 61(fn.32), 62(fns.36-37), 70(fn.111), 72, 75, 75(fn.3), 84-85, 87, 96(fn.41)

Shaw, WBK: 123-124, 124(fn.25), 127(fn.57)

Shelkota Meidob: 116, 116(fn.4), 121

Shendi: 27, 27(fn.53), 28(fn.65), 30(fn.78), 125(fn.37)

Sherkayla: 50

Shilluk: 8(fn.15), 34(fn.26), 75, 75(fn.2), 123

Shimir: 55

Shinnie, Peter: 11, 13, 67, 67(fn.86), 73(fn.144), 74, 113, 113(fn.1), 127, 127(fn.56), 132, 135

Shirim: 88

Shoba: 90

Showaia: 96(fn.38)

Showunga Tunjur: 59

Shu (Egyptian God): 54

Shuqayr, Naum; 89

Shuwa Arabs: 44

Si Dallanga: 54

Siesa: 71

Sigato: 119

Sikar: 91

Simiat Hills: 33

Sinnar (Sennar): 5, 27, 27(fn.55), 28(fn.65), 30(fn.78), 38(fn.58), 43, 87, 88(fn.18), 89(fn.28), 126, 126(fn.44), 129

Sira al-Hilaliya: 49

Sitting Burial: 31(fn.5), 119(fn.42)

Sira al-Hilaliyya: 49

Sirma: 59

Slatin Pasha, Rudolf: 1, 29, 51, 78(fn.14)

Slaves, Slavery: 27(fn.55), 34, 71, 87-89, 96, 120(fn.46), 140

Snakes in Religious Rites: 78-79

Soba: 62(fn.36), 65(fn.67), 66, 122, 123, 124, 124(fn.29), 126-127, 126(fn.44), 127(fns.47,56), 131

Sobat River: 31(fn.4), 75

Solomon: 39

Songhay: 135

Songs: 80

Sopo River: 23

South Africa: 15

South Sudan: 35

Spain, Spanish: 54, 110, 137

Spaulding, Jay: 50, 64(fn.57), 112, 112(fn.25)

Stevenson, RC: 23

Stewart, Andrew: 38

Stone Circles: 118(fn.27), 124, 129

Stone Worship: 61(fn.30), 72, 72(fn.129), 86, 87(fn.9), 117-119, 139

Suakin: 127(fn.58)

Subhanin: 25, 25(fn.29)

Sudan Notes and Records: 7, 8

Sudan Political Service: 7, 8

Sufyan, King: 85

Sufyan al-Thawri: 37

Sulayman (founder of Bilia Bidayat): 48

Sulayman al-Abyad: 89

Sulayman Solong (Sliman, Solongdungo), Sultan: 43, 55(fn.111), 59, 59(fn.15), 70, 70(fn.111), 78(fn.14), 87-88, 89, 93, 93(fn.10), 94-96, 96(fn.41), 118, 120(fn.46), 131, 139

Sun Worship: 77(fn.9)

Sunghor (Sungor): 36(fn.41)

Suni Valley: 94

Supreme Court of Canada: 14-15, 15(fn.33)

Syria. Syrian: 50, 68

T

Taberber: 28(fn.64)

Taboos: 96(fn.38)

Tabun, Shartai: 31

Tagabo Hills: 116-119, 119(fn.36), 119(fn.38)

Tahir, Basi: 28

Tahrak, King: 129

Taiserbo: 31(fn.5)

Taitok: 14, 14(fn.29)

Tageru Hills: 128

Taharqa, King: 129(fn.79)

Tajia (Tagia): 38(fns.57-58)

Tajuwa: 22-23, 33, 112(fn.20)

Takaki (Tekaki): 66(fn.76), 71(fn.120)

Tari: 134

Al-Taka: 129, 129(fn.78),

Takamat: 13-14

Tama: 27(fn.31), 36(fn.41), 45(fn.21)

Tamachek: 45(fn.25)

Tamurkwa (Tamurka) Fur: 86, 86(fn.4), 87

Tanit: 14

Tanjak: 55

Tanjikei: 36(fn.41)

Tanzania: 10, 115,

Tar Lis (Tarlis): 112

Tari: 132

Taruga: 114

Tartari: 135

Tatars: 36(fn.44)

Al-Tayeb, Shaykh: 29(fn.66), 99

Tchertcher Mountains: 128(fn.68)

Tebeldi Trees: 3-4, p.3 (fn.5)

Teda: 16, 16(fn.5), 22, 22(fn.4), 34(fn.29), 45, 47, 47(fn.45), 48, 48(fn.47), 119, 128

Tedagada: 45

Tedjeri (Tejeri): 119(fn.41)

Teiga Plateau: 117

Tamaragha Doka, Shaykh: 129(fn.81)

Temeh: 45(fn.21)

Ten Tribes of Israel: 36(fn.44)

Termit: 113

Terninga, Sultan: 27

Teqaqi: 71

Tesseti Dynasty: 116

Thamud: 28(fn.65)

Thelwall, Robin: 117, 120

Thurro: 75

Thutmosis III: 46, 46(fn.35), 134

Thutmosis IV: 8

Tibesti (Tu): 5, 8, 16, 20, 31(fn.5), 45, 45(fn.23), 46(fn.32), 47, 47(fn.46), 48, 48(fn.51), 54, 64(fn.58), 113, 119, 128(fn.68), 130, 136-137

Tibet: 35

Tidikelt: 14(fn.29)

Tidn-Dal Language: 116

Tié: 67(fn.86), 73, 73(fn.144), 74

Tifinagh: 14, 70, 70(fn.108)

Tilho, Commandant: 77, 132, 132(fn.4)

Timsah: 28(fn.64)

Tin Hinan: 13-14 13(fn.25), 14(fn.29)

Tine: 88, 94(fn.21)

Tirga umm sot: 33, 33(fn.18),

Tit: 20(fn.21)

Tiv: 13

Togoland: 5

Togonye, Togoinye: 34, 34(fn.25)

Tong Kilo: 94, 97(fn.46)

Tong Kuri: 93

Tongoingi (Togoingi): 34(fn.25)

Tora: 16-21, 31, 33, 44, 53, 57, 59, 60, 61, 62, 64, 65, 66, 72, 90, 91, 91(fn.5), 94, 95, 95(fn.31), 97, 119, 123, 126, 127, 128, 128(fn.68), 131

Toronga Kuroma: 16, 17-18

Torti Meidob: 116

Toschka: 134

Tounjour Wells: 132, 132(fn.6)

Tow: 54

Transmogrification: 86,

Treinen-Claustre, F: 134

Tréya (see Jebel Tréya)

Trigger, Bruce: 8, 120

Tripoli: 4, 60, 63(fn.47), 70(fn.111), 77, 77(fn.1), 117, 137

Tuareg (see also Kinin): 13-14, 34(fn.29), 36(fn.44), 43(fn.3), 45, 46(fn.32), 64(fn.53), 128, 130, 130(fns.93,96)

Tubba Kings: 38, 111(fn.12)

Tubiana, J.: 43, 63

Tubu (Tibu, Tibbu): 16, 27(fn.54), 34(fn.29), 44, 44(fn.8), 45, 46, 46(fn.27, 30, 31), 47(fn.46), 48(fn.51), 49, 56, 64(fn.53), 75(fn.3), 117, 130, 137, 139, 140

Tubu Genealogy: 47(fn.46)

Tukl: 20, 61(fn.31), 65-66, 69

Tumaghera: 45-48, 45(fn.25), 46(fn.26), 46(fn.31, 32), 47-48, 47(fn.43), 47(fn.46), 48(fn.51), 54, 113, 140

Tumaghera of Tibesti, Sections: 47, 47(fn.46)

Tumam Arabs: 8

Tumsah (see Tunsam)

Tuna: 59

Tunis: 20, 36(fn.41), 44, 49, 50, 52, 63, 77(fn.1), 80

Tunis (Kanem): 80(fn.1)

Tunisia: 20(fn.22), 52, 73, 74

Al-Tunisi, Muhammad ‘Umar: 5, 27(fn.55), 28(fn.65), 37(fn.54), 43, 57(fn.2), 64(fn.53), 72(fn.134), 77(fn.9), 120(fn.46)

Tunjur: 5, 10, 12, 16, 18, 25, 26, 28, 28(fn.64), 28(fn.65), 29(fn.71), 30, 30(fn.74), 31, 33, 34(fn.25), 36(fn.41), 43-85, 43(fn.6), 44(fns.8, 15), 45(fn.18), 45(fn.19), 46(fn.31), 47(fn.46), 48(fn.47), 48(fn.53), 48(fn.54), 51(fn.71), 52(fn.86), 53(fn.90), 55(fn.111), 57(fns.2,5), 59(fn.15), 62(fn.37), 62(fn.42), 63(fn.47), 72(fn.128), 75(fn.3), 77(fn.6), 80(fns.1,2), 84(fn.3), 87, 88, 88(fn.21), 91, 95, 97, 111, 111(fn.11), 112, 113, 118, 119, 120(fn.46), 131, 132, 132(fn.6), 134, 139

Tunjur, Sultan: 30, 43

Tunjur-Fur: 43, 64(fn.60), 70

Tunjur of Kanem, Sections: 44(fn.13)

Tunjur King-Lists: 81-85

Tunjur Language: 44(fn.8), 63, 64(fn.54)

Tunjur Sections (Darfur): 43

Tunjur Wara: 59

Tunsam (Tumsah), Sultan: 28(fn.64), 31, 49, 70, 84, 87, 89, 93, 93(fns.8,10), 139

Tura: 47

Turco-Egyptians: 12, 62(fn.36)

Turi: 54, 57(fn.1)

Turks (see also Ottomans, Turco-Egyptians): 36(fn.44), 63, 70(fn.111), 74

Turkish Language: 74, 77(fn.9)

Turra: 16, 18, 27, 53, 57, 59, 69, 70, 91(fns.2,3), 93(fn.8), 95-97, 96(fn.43), 97(fn.45), 97(fns.46,47), 99

Turra Hills: 91

Turti: 35

Turrti Dynasty: 118, 121

Turuj: 8, 27(fn.55), 33

Turza: 120(fn.46)

Al-Tuwaysha: 119

U

Ubangi River: 110(fn.3)

Udal, John O.: 75, 75(fn.3)

Uddu: 86

Ufa, King: 29

Uganda: 14, 18

Um Bura: 64(fn.53)

Um Bus Masalit: 78(fn.14)

Um Daraj (Durraj): 129-130

Um Kurdoos: 28

Umangawi: 78(fn.14)

‘Umar, Daju King: 28

‘Umar, Tunjur Sultan: 77

‘Umar ‘Ali: 45

‘Umar Kissifurogé: 28, 29-30, 33

‘Umar Lel, Sultan: 27, 89, 95

‘Umar ibn Muhammad Dawra – see Muhammad Dawra

Umm Kiddada: 119

Umm Harraz: 94

Umm Harot: 125

Umm Shaluba: 73(fn.148), 77

Ummayads: 48, 49, 51

Umunga Fur: 33

Upper Nile Province: 34(fn.26)

Uri: 27, 28(fn.64), 44, 56, 57, 57(fns.2,5), 59, 60-64, 60(fn.23), 60(fn.24), 61(fn.30), 62(fn.37), 63(fns.46,47), 64(fn.58), 65(fn.65), 68-69, 70, 70(fn.111), 72, 73, 74, 93, 112, 112(fn.21), 119, 119(fn.38), 122(fn.6), 139

Urimellis: 64

Urti Meidob: 116, 121

V

Venda: 15

Vansleb, JM: 64, 112(fn.25)

Vantini, G: 134

Vatican: 137

Veil – see Litham

Venice, Venetian: 63, 63(fns.47,49)

Vienna Manuscript: 51(fn.74)

Vogel, Dr. Edward: 78

W

Wadai: 5, 8, 21, 25, 26, 27, 27(fns.54,55), 28, 28(fn.65), 28(fn.65), 33(fn.18), 34, 36(fn.41), 43, 44, 45, 45(fn.21), 46, 48, 48(fn.53), 48(fn.54), 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57(fn.2), 59, 62, 64(fns.53,54), 71, 72(fns.128,129), 74, 75(fns.3,7), 77-79, 77(fns.1,6), 83, 86, 88-89, 95, 110, 111, 111(fn.11), 112(fn.24), 120(fn.46), 128, 132, 134, 135, 140

Wadai, Aboriginal groups: 25

Wadi Abu Dom: 134

Wadi Abu Hashim: 125

Wadi Abu Sibaa: 124

Wadi al-Anaj: 127(fn.57)

Wadi Barei: 94(fn.21), 95

Wadi Golonut: 118

Wadi Halfa: 8, 68(fn.97)

Wadi Hawar (Howar): 4, 9, 47, 125

Wadi Howa: 77

Wadi Jeldama: 95

Wadi Jugtera: 64(fn.53)

Wadi Magrur: 117

Wadi al-Melik (Milk): 4, 117, 122(fn.6), 123, 125, 127

Wadi al-Mukaddam (Muqaddam): 117, 125

Wadi al-Sabt: 38

Wadi Tunsam: 93

Wadi Umm Shaluba: 44

Wadi Uri: 64(fn.58)

Wahb bin Munabbih: 6, 37, 37(fn.52)

Al-Wahwah: 37(fn.46)

Walool: 126

Walz, Terrence: 54

Wamato: 119(fn.37)

Wandala: 136(fn.32)

Wansborough, John: 11

Wara: 33(fn.18), 43, 45, 55, 59, 74, 77-79, 77(fn.6)

Wastani: 36(fn.41)

Wathku: 23

Wau: 23(fn.15)

Wawat: 8

Western Field Force: 1-2

White Nile: 31(fn.4), 50

Wickens, GE: 18-20

Wirdato Meidob: 116, 118

“Wise Stranger” (see also Ahmad al-Ma’qur): 10, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 46, 48, 49-52, 50(fn.64), 56, 87, 119

X

X-Group: 124(fn.29)

Y

Yahia: 27(fn.31)

Yame: 28(fn.65), 43

Yao: 111(fn.11)

Ya’qub ‘Arus, Sultan: 88

Ya’qub Bok Doro, Sultan: 30

Al-Ya’qubi: 22, 128

Yaqut bin ‘Abd Allah al-Hamawi: 22(fn.4)

Yasir: 39

Yemen: 25, 26, 26(fn.38), 29(fn.73), 37, 38, 49, 111(fn.12), 125(fn.33), 136

Yér: 27(fn.55)

Y’nk: 128

Yusuf, Prince: 89

Yusuf As’ar Yath’ar (Dhu Nuwas): 26(fn.38), 136

Z

Zaghawa: 22, 22(fn.4), 23, 23(fn.8), 25, 27, 29(fn.71), 36(fn.41), 49(fn.55), 50(fn.67), 63-64, 64(fn.53), 72(fn.128), 77, 88, 89, 112(fn.20), 114(fn.16), 119, 136

Zaghay: 23

Zakaria: 69

Zalaf, King: 28, 29

Zalingei: 86

Zanata Berbers: 49,

Al-Zanati, Khalifa: 49

Zanj: 22, 23, 23(fn.8)

Zankor: 66(fn.75), 122-123, 122(fns.2,6), 123(fn.13), 127, 127(fns.53,56), 130, 131, 134

Zarroug, Mohi al-Din Abdalla: 127

Zayd: 36(fn.41), 51

Zayadiya Arabs: 36(fn.41), 51

Zayn al-‘Abidin de Tunis: 77(fn.9)

Zeltner, Jean-Claude: 44

Zenata: 128(fn.68)

Zeugatania: 137

Zeus Ammon: 37-38

Zhylarz, Ernest: 46(fn.35), 120(fn.48)

Ziegert, H: 9

Zingani: 137(fn.37)

Al-Zubayr Pasha: 11(fn.10), 12, 62(fn.38), 87, 96

Zurla: 63

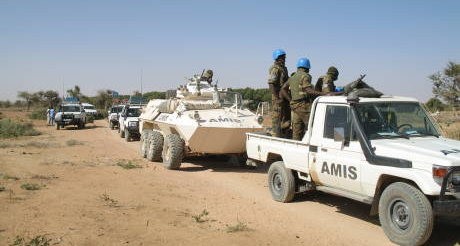

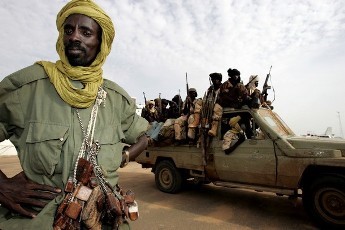

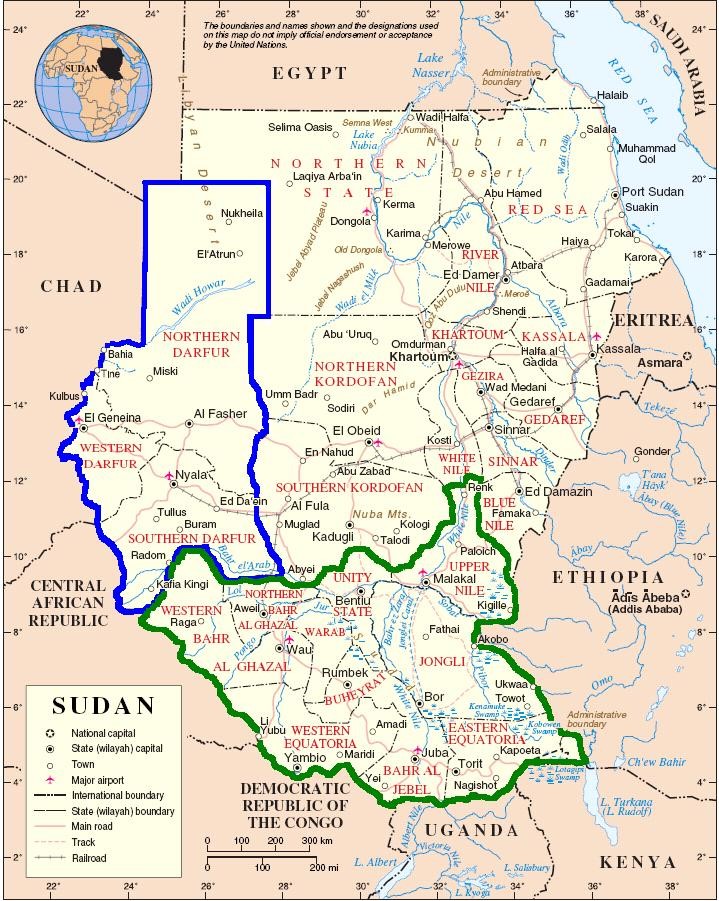

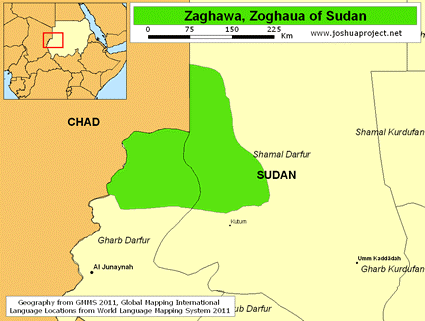

JEM is usually regarded as a Zaghawa-dominated movement, based on the semi-nomadic African tribe that straddles the Chad/northern Darfur border. JEM leaders are probably the most experienced and sophisticated of all the many rebel movements in Darfur, giving the movement a weight unjustified by its numbers. Many Zaghawa became skilled and innovative desert fighters during the Chadian civil war and the campaign against Libyan garrisons in northern Chad. The conflict in Darfur is, in part, a reflection of the growing assertiveness of the Zaghawa, who already dominate the government in Chad. In Sudan, the Zaghawa now present a commercial challenge to Arab dominance of the economy. Zaghawa factionalism, however, has prevented the development of a unified Zaghawa movement. In recent months, JEM has made efforts to broaden its ethnic base, including sacking the group’s military commander, who was accused of favoring the Zaghawa.

JEM is usually regarded as a Zaghawa-dominated movement, based on the semi-nomadic African tribe that straddles the Chad/northern Darfur border. JEM leaders are probably the most experienced and sophisticated of all the many rebel movements in Darfur, giving the movement a weight unjustified by its numbers. Many Zaghawa became skilled and innovative desert fighters during the Chadian civil war and the campaign against Libyan garrisons in northern Chad. The conflict in Darfur is, in part, a reflection of the growing assertiveness of the Zaghawa, who already dominate the government in Chad. In Sudan, the Zaghawa now present a commercial challenge to Arab dominance of the economy. Zaghawa factionalism, however, has prevented the development of a unified Zaghawa movement. In recent months, JEM has made efforts to broaden its ethnic base, including sacking the group’s military commander, who was accused of favoring the Zaghawa.