Andrew McGregor

April 16, 2008

For two decades Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) has plunged northern Uganda into a nightmare of atrocities, sadistic mutilations, child-kidnappings and sexual slavery, all in the name of establishing a Ugandan government based on the Bible and the Ten Commandments. After years of fighting and recent internal dissension, the elusive LRA consists today of little more than 800 individuals, including kidnapped children and young women abducted and given as rewards to loyal LRA commanders. At least half its fighters are believed to be children kidnapped from north Uganda, though many older fighters appear to be drawn by opportunities for looting or even commitment to the cause of Acholi rights.

(Economist)

The Acholi-based LRA has its roots in the 1986 overthrow of Uganda’s Acholi ruler, General Tito Okello, by Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA). The Acholi are a sub-group of the Luo people of South Sudan’s Bahr al-Ghazal region who migrated to northern Uganda several centuries ago. Traditionally a dominant force in the Ugandan army, Acholi who feared a loss of influence in the new regime started a host of insurgent groups in north Uganda, many with religious and millennial overtones, such as Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement. Infused with religious zeal, these movements initially adopted bizarre and frequently suicidal military methods such as using holy water to deflect bullets and attacking in cross-shaped formations.

LRA political manifestos, often written by diaspora Acholis, have had little resonance, partly because of successful attempts by the Kampala government to depict the LRA leadership as irrational and obsessed by religious fundamentalism. Typically these statements contain detailed criticism of Museveni’s one-party rule and call for Ugandan federalism, multi-party politics, free elections and broad political reforms [1].

LRA leader Joseph Kony failed to show up on April 10 for the long-awaited signing of the Final Peace Agreement (FPA), designed to bring a negotiated end to years of brutal violence in north Uganda. According to Ugandan government negotiators, all five phases of the complex agreement have been settled and all that remains is the ceremonial signing that will end the LRA’s 21-year “insurgency.” Kony’s failure to appear and sign the peace agreement may mark a bitter conclusion to two years of intensive negotiations brokered by Riek Machar, a former Nuer militia leader and current vice-president of the semi-autonomous Government of Southern Sudan (GoSS). With the Juba ceasefire agreement of August 2006 set to end on April 16, Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni has indicated the Ugandan People’s Defense Forces (UPDF) may be ready to resume operations against the LRA (New Vision [Kampala], April 14; Sudan Tribune, April 14).

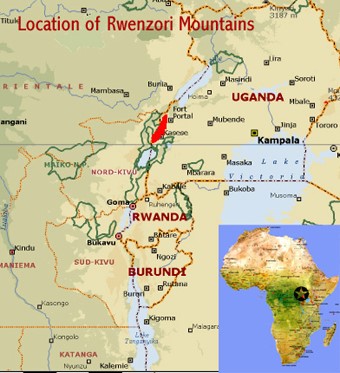

Supported since 1994 by the Sudanese government as a proxy in Khartoum’s war against the Ugandan-backed Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) in south Sudan, the conclusion of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) brought an end to the civil war and ended Khartoum’s need for the LRA. No longer secure in their bases along the Sudanese side of the border with Uganda, the LRA moved into the wilds of Garamba National Park in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In February Kony led nearly 200 followers into the southeastern Central African Republic (CAR), where they established a new base at Gbassiguri. Once settled, they attacked the CAR village of Obo in early March, abducting over 100 children and adolescents (Daily Monitor [Kampala], March 12; April 10). There are unverified reports that Kony’s group has joined up with a Chadian rebel movement also using the CAR as a base (New Vision, March 23). The area in which the LRA has settled is controlled by the rebel People’s Army for the Restoration of the Republic and Democracy (PARRD) which claims to be fighting the CAR government of President Francois Bozize. Both the Chadian rebels and the PARDD are alleged to be supported by Khartoum (Daily Monitor, February 26).

Kony appears to be using his new base in the CAR to attack his former hosts in South Sudan; on February 19 about 400 LRA fighters raided the Western Equatorian town of Source Yubu, killing seven SPLA soldiers and 11 civilians while abducting 27 people (New Vision, February 27).

The ceasefire agreement calls for all LRA fighters to assemble at Ri-Kwangba, in South Sudan’s Western Equatoria province, for final disarmament and demobilization. Some fighters have gathered nearby, but remain in the bush except for collecting their food rations. Most of Kony’s commanders and several hundred fighters appear to have remained behind at Gbassiguri rather than come in to Ri-Kwangba.

Kony’s chief negotiator, David Nyekorach Matsanga, claimed that the LRA leader had come in from the CAR and was in the bush nearby, but later admitted that he had had no contact with Kony for four days before the aborted signing of the FPA. The UK-based Matsanga was arrested by South Sudanese troops on his way to Juba airport on April 13 after being fired as chief negotiator by Kony. Matsanga was carrying $20,000 in cash and a letter to Kony from Yoweri Museveni (Sudan Tribune, April 14).

Kony has repeatedly said that a peace agreement is only possible if the 2005 International Criminal Court (ICC) indictments against him are dropped. To accommodate Kony and other LRA leaders, Uganda’s negotiators have proposed a mixture of mato oput (the traditional Acholi system of reconciliation rituals) for lesser crimes and recourse to a special Ugandan High Court for more serious offenses. The use of mato oput, which emphasizes reconciliation rather than punishment, is favored by Uganda’s chief justice, Benjamin Odoki, as well as many Acholi elders who are desperate for an end to the years of LRA terror and often ruthless retaliation from the UPDF (New Vision, May 17, 2007). Nearly two million internally displaced people are also ready to forgo ICC justice in order to return to their homes. The High Court could still charge Kony with various penalties subject to the death penalty, such as treason, murder and rape (Daily Monitor, February 20).

Having been invited into the process by the Ugandan government in 2005, however, the ICC is not so easy to dismiss when it becomes inconvenient. When the LRA began to move out of its traditional area of operations along the Sudanese-Ugandan border, Uganda invited international assistance through the ICC. The ICC responded by issuing indictments for war crimes and crimes against humanity against Kony and four other LRA leaders: Okot Odhiambo, Vincent Otti, Dominic Ongwen and Raska Lukwiya. Official Ugandan efforts to have the ICC drop the charges have failed; even Riek Machar’s attempt to depict the ICC as “European justice” has had no impact. Two lawyers representing the LRA have arrived in The Hague to file for the withdrawal of the indictments (New Vision, March 19). Under ICC rules, Kampala cannot request the suspension of arrest warrants once issued, even if Uganda were to reverse the ratification of its agreement to sign on to the ICC.

Late LRA Second-in-Command Okot Odhiambo

Late LRA Second-in-Command Okot Odhiambo

With the apparently aimless LRA stripped of its major sponsor and forced farther and farther from its north Ugandan homeland, there is intense internal pressure within the movement to conclude some sort of peace agreement with the Ugandan government. Over the last year Kony has typically dealt with these challenges through bloodshed within his own movement, culminating in the massacre last week in Garamba National Park of his deputy, Okot Odhiambo, and eight other commanders (Daily Monitor, April 14; AP, April 15). Of the five LRA leaders originally charged by the ICC, only Kony and Dominic Ongwen remain alive. Before his execution by Kony last October, LRA deputy leader Vincent Otti was a personal friend of Riek Machar and an advocate of negotiating a peace agreement. Several Otti loyalists surrendered to South Sudanese authorities in 2007 while Otti and his remaining followers were eliminated during and after a gun battle with Kony loyalists (Sudan Tribune, October 23, 2007; Reuters, December 1, 2007; Sudan Tribune, January 24). Raska Lukwiya was killed by the UPDF in August 2006.

There are signs that the continued survival of the LRA is in part due to corruption within the UPDF that has aided and at times abetted Kony’s movement. An ongoing investigation into the commanders of the UPDF’s 4th and 5th Divisions—operating in north Uganda—has revealed that as much of 50 percent of the strength of these units consisted of “ghost soldiers,” non-existent troops for whom salary was still drawn from the central government. The unneeded arms issued for these “ghost soldiers” may have been sold to the LRA for cash. Major-General James Kazini and two other senior officers were sent to prison late last month after being described by the committee of investigation as “conflict entrepreneurs” (Daily Monitor, March 31). There are also charges that Ugandan troops have misused permission given to mount cross-border operations against the LRA in Southern Sudan (Operation “Iron Fist”) to harvest valuable teak forests (VOA, September 29, 2007). The LRA has also been used in an attempt by Uganda to tap into funds available for fighting the War on Terrorism; according to Uganda’s External Security Organization (ESO) Director-General Robert Masolo: “You will recall that bin Laden was training the LRA into killer squads in Sudan, alongside other al-Qaeda terrorists who he was exporting to other parts of the world” (New Vision, June 12, 2007).

There are suggestions that the FPA might be signed in the absence of Joseph Kony, though such an act would be essentially meaningless as Kony’s brigands continue to raid isolated villages in the CAR and DRC. President Museveni has warned that the rebels can only expect to save themselves through signing the FPA: “If they don’t, they will perish” (New Vision, March 10). Kony’s refusal to appear has been a major embarrassment for Kampala and could be the signal for an all-out offensive against the movement to be carried out in cooperation with DRC authorities, who are also trying to bring an end to lawlessness in the eastern Congo.

This article first appeared in the April 16, 2008 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Focus

Note

1. Mareike Schomerus, “The Lord’s Resistance Army in Sudan: A History and Overview,” Small Arms Survey, Geneva, 2007.