Andrew McGregor

July 13, 2006

The brazen Baghdad kidnapping of four Russian embassy employees took place on June 3, only 400 meters from the Russian embassy. Violating the embassy’s own security protocols, an embassy vehicle stopped at a local grocery store (on an unauthorized alcohol run, according to Kommersant on June 27), where it was immediately blocked on both ends by other vehicles containing machine-gun-firing assailants. Vitalay Titov, a security official, was killed in the attack, while the third secretary of the embassy, Fedor Zaitsaev, and three embassy employees, Anatoli Smirnov, Oleg Fedoseev and Rinat Agluilin (a Muslim), were packed into a minibus that fled the scene. U.S. troops from the adjacent Green Zone headquarters of the U.S. military arrived with Iraqi police within minutes, but were unable to pick up the trail of the kidnappers.

The kidnapping was well-organized. The stop was anticipated, implying previous surveillance of the targets and their habits. The lone security agent was quickly identified and neutralized with the entire scene cleared of assailant vehicles, personnel and hostages within moments. A safe-house and its security arrangements were arranged in advance. In all, it was a highly professional operation followed by a puzzling lack of communication from the kidnappers. There was no claim of responsibility, no political demands and no ransom requirements. In the meantime, Iraqi and coalition forces failed to find any trace of the kidnappers.

A Chechen Connection?

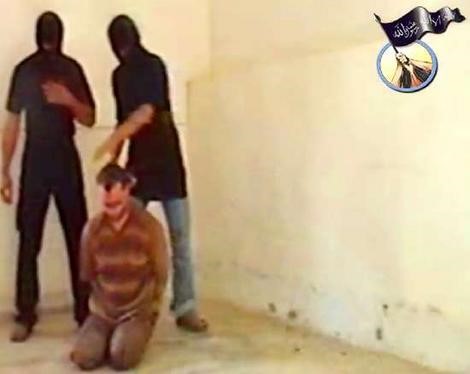

Styling themselves as Iraq’s “lions of unification,” the Mujahideen Shura Council (MSC) issued a statement on June 19 claiming responsibility for the kidnapping and threatening to kill the hostages unless Russia withdrew its military from Chechnya and released all Muslims from prison within 48 hours. On June 21, the MSC, an umbrella group of anti-coalition/Iraqi government insurgent groups that includes al-Qaeda in Iraq, stated that all the hostages had been killed after Russia failed to comply with their demands. When a video of the beheadings was released on June 25, it was surprisingly dated June 13, six days before the MSC released its demands. An al-Qaeda logo was prominently stamped on the video footage as a voice-over declared that “God’s verdict has been carried out.” The video showed the beheadings of two hostages and the shooting of a third. The video did not include the murder of the fourth hostage.

Since the September 11 attacks, Russia has had limited success in portraying itself as a victim of an al-Qaeda plot to establish an Islamic Caliphate on Russian territory. In the scenario painted by the Kremlin, Chechnya’s Muslim separatists are a terrorist cohort operating under the orders of Osama bin Laden. The impossible demands issued by the MSC reinforced this perception, creating an all-important al-Qaeda-Chechen “link,” days prior to the Moscow-hosted G-8 conference. It should be noted that it is impossible to verify the authenticity of the MSC statements. Strangely enough, the leader of the MSC, Abdullah bin Rashid al-Baghdadi, issued communiqués on June 16 and July 1, neither of which referred to the kidnappings despite their international importance.

Chechen leaders of the region’s Russian-backed government responded angrily to the demands. The speaker of the lower house of parliament, Dukvakha Abdurakhmanov, protested “the use of the name of the Chechen people by terrorists of various hues in their criminal aims…Russia is our homeland and its troops are located where they should be located” (Interfax, June 20). Russian-backed Chechen President Alu Alkhanov condemned the kidnapping as a provocation and an “encroachment on the Chechen Republic and its people.” The rival separatist government also roundly denounced the kidnappers’ demands while insisting on the release of the hostages. According to the Chechen separatist foreign minister, Akhmed Zakaev, the kidnapping was “a provocation by Russian special services designed to implicate the Chechen struggle in international terrorism.”

Russia’s “Islamic Card”

Shortly after the kidnappings, Co-Chairman of the Council of Russian Muftis Nafigulla Ashirov suggested that the abductions were the work of Western intelligence agencies. He said, “Political analysis and common sense would suggest those who are dissatisfied with Russian policy, which runs counter to the hegemonic intentions of the U.S. and the Western world.” Ashirov’s comments were supported by Abdul-Wahid Niyazov (a powerful Russian politician and convert to Islam), who alluded to the work of the same “special services that started the war in Iraq” (Interfax, June 9). Russia’s leading mufti, Talgat Tadjuddin, suggested that the kidnapping “serves the interests of the enemies of Iraq” (Interfax, June 21). Tadjuddin, who was very close to the Saddam Hussein regime, has in the past referred to President George W. Bush as “a drunken cowboy” and “the anti-Christ of the world.”

At one point, a Russian Foreign Ministry spokesman presented a revisionist portrayal of Russian/Islamic history: “Russia is a multifaith country in which representatives of two great religions—Orthodoxy and Islam—have lived in peace and accord for centuries.” The spokesman added that the abductees “are representatives of the Russian people, which has never waged war anywhere against Islam” (Interfax, June 21; RIA Novosti, June 21). In Shiite Iran, where Russia is assisting in nuclear development projects, the foreign ministry offered to use its influence in Iraq to help free the hostages (RIA Novosti, June 25).

Murder and Response

In Russia, there was widespread criticism that the federal government had displayed little interest in the rescue of the hostages. FSB head Nikolai Patrushev announced a US$10 million reward for information leading to “a result” in the hunt for the murderers, but retired General Leonid Ivashov described the attitude of the authorities as “criminally negligent” (Ekho Movsky Radio, June 26). The Russian Duma passed a unanimous statement declaring that the deaths were the result of the coalition “losing control” in Iraq (Itar-Tass, June 28). Suggestions of U.S. culpability through the insufficient provision of security in Baghdad became the focus of a heated exchange between Condoleezza Rice and her Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov at the G-8 foreign ministers’ meeting.

There was also considerable media speculation on the role of U.S. secret services in the affair. Iraq’s former ambassador to Moscow, Abbas Halaf, declared on Russian radio that the murders were intended to punish Russia for its stand against “American aggression” in Iraq and its support for the Palestinian people (Ekho Movsky Radio, June 26). The current Iraqi ambassador, Abdulkarim Hashim Mostafa, described the MSC as foreign-led representatives of the Iraqi Baathist regime while describing his government’s interest in Russian training for Iraqi security services (the usual practice in pre-war Iraq) (Interfax, June 28). In some quarters, the abductions have been interpreted as a warning to Russia to limit the activities of their secret services in Iraq and to temper Russian posturing as a non-threatening friend of the Iraqi government, in contrast to the “colonial ambitions” of the United States.

The Kremlin’s response to the deaths was dramatic, with President Putin ordering Russia’s secret services to “destroy” those responsible. FSB head Nikolai Patrushev promised that these instructions would be carried out “no matter how much time and effort is required” (Interfax, June 28). Putin immediately issued a resolution that called for granting Russia’s president the right to deploy armed forces and special-purpose units outside Russia to prevent “international terrorist activity.” Despite opposition concerns of a return to Stalinist tactics, the Russian Duma passed the legislation unanimously on July 5, followed by the unanimous approval of the upper house on July 7. There is no expiration date for the extraordinary powers. According to the chairman of the council’s Defense and Security Committee, Viktor Ozerov, the special services will conduct their operations abroad in secret, with the president having the option of revealing such activities to the Russian public “when necessary” (Itar-Tass, July 7).

President Putin claims that the new legislation is in line with Article 51 of the UN Charter, which refers to “the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a Member of the United Nations.” Bush administration legal experts have cited the same article as permitting “anticipatory” self-defense and used it to justify the assassination of al-Qaeda member Ali Qaed Sinyan al-Harthi in Yemen in 2002. Putin added that the charter does not say that the aggression must originate with another state (RIA Novosti, July 7). Russia first announced a new policy of using pre-emptive military force against external threats in October 2003.

Besides the GRU (Russia’s military intelligence agency), another candidate for the job of eliminating the murderers is a subunit of the Foreign Intelligence Service known as Zaslon (Shield), created in 1998 and composed of at least 300 military veterans (Izvestia, July 4). Both Zaslon and the GRU had a presence in Baghdad before the 2003 U.S. invasion and have ties to former members of Iraqi intelligence. There is no reason to attribute special skills to Russia’s present secret services in this type of operation. Their last attempt in this field, the successful assassination of Chechen ex-president Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev in 2004, was nevertheless so ineptly handled that the agents responsible were quickly arrested and considerable international embarrassment resulted for Moscow.

Conclusion

Is this merely a case of pre-G-8 summit posturing on Russia’s part? Aiming hit squads at Iraq would risk a great deal, with only a remote chance for success. Interference in a U.S. theater of operations could threaten relations with the United States, relations that Russia seeks to modify, not destroy. Indeed, as Putin awaited approval of his new powers, he spoke of Russia and the United States together bearing “special responsibility for world security” (Itar-Tass, July 6). Tactical mistakes could also jeopardize Russian influence in Iraq and Iran. Once in Iraq, how long would the presence of Russian Special Forces be tolerated? Clearly, such activities would come into conflict with coalition operations unless carefully coordinated; for instance, there could be a repeat of what occurred on July 4, 2003 when U.S. soldiers detained and hooded a team of Turkish special forces in Iraq, an incident that infuriated Turkey. On the other hand, coordination with Russian operatives would inevitably be regarded as international approval for extra-territorial operations by Russia’s security agencies.

Infiltrating Iraq’s fluid and complex web of resistance groups will be a far different task than assassinating the unprotected Yandarbiyev. If the Russians are serious, they will need to recruit and depend on Iraqi operatives. Russian agents would be even more conspicuous in Iraq than in Qatar, where the local security service monitored every move and phone call made by the Russian assassins from the moment they stepped off the plane. Russia’s legalization of retribution is a simple matter compared to operational demands in Iraq and the need to deal with the consequent international implications.

This article first appeared in the July 13 2006 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor