Andrew McGregor

October 28, 2011

Mali, like its neighbor Niger, is facing the return of an estimated 200,000 of its citizens from Libya. Most are Malian workers and their families who have been forced to flee Libya by the virulently “anti-African” forces that have seized power in that country. Some, however, are long-term Tuareg members of the Libyan military who have suddenly lost their jobs but not their arms. Armed Tuareg began returning to northern Mali in large numbers in August and continue to arrive in their homeland in convoys from Libya (El-Khabar [Algiers], August 29).

Unfortunately, Mali has nothing to offer these returnees; not aid, not employment, nor even a sense of national identity; in sum, nothing that might provide some counter-incentive to rebellion. Disenchantment with the West is at an all-time high among the Tuareg. Even the French have fallen from favor; while the Tuareg could once count on a sympathetic reception in Paris and from elements of the French military, in the last few months Tuareg fighters have found themselves on the receiving end of French airstrikes and their home communities attacked by French-armed rebels. Both France and the United States have also made extensive efforts to train and equip the generally ineffective and cash-strapped militaries of Mali, Niger and several other Sahara/Sahel states in the name of combatting terrorism, improvements that run counter to Tuareg interests. A Malian government minister was quoted by a French news agency as saying the returning Malians were really a Libyan problem: “They’re Libyans, all the same. It’s up to the Transitional National Council [TNC] to play the card of national reconciliation and to accept them, so that the Sahel, already destabilized, doesn’t get worse” (AFP, October 10).

Pro-Qaddafi Tuareg Fighters in Libya

Another 400 armed Tuareg arrived in northern Mali from Libya on October 15, with many keeping their distance from authorities by heading straight into the northern desert (Ennahar [Algiers], October 18). Their arrival prompted an urgent invitation from Algeria for President Touré to visit Algerian president Abdel Aziz Bouteflika (Maliba [Bamako], October 17). According to Malian officials, the returned Tuareg were in two armed groups; the first with some 50 4×4 trucks about 25 miles outside the northern town of Kidal, the second consisting of former followers and associates of Ibrahim ag Bahanga grouped near Tinzawatene on the Algerian border (Reuters, October 20; L’Aube [Bamako], October 13). An ominous development was the recent desertion of three leading Tuareg officers from the Malian Army, including Colonel Assalath ag Khabi, Lieutenant-Colonel Mbarek Akly Ag and Commander Hassan Habré. All three are reported to have headed for the north (El Watan [Algiers], October 20).

Colonel Hassan ag Fagaga, a prominent rebel leader and cousin of the late Ibrahim ag Bahanga who has already deserted the Armée du Malitwice to join rebellions in the north, was given a three-year leave “for personal reasons without pay” by Maliian defense minister Natie Plea beginning on July 1, apparently for the purpose of allowing ag Fagaga to lead a group of young Tuareg to Libya to join the defense of Qaddafi’s regime (Le Hoggar [Bamako], September 16). Ag Fagaga is now believed to be back in northern Mali, preparing for yet another round of rebellion.

The Malian government’s response to these developments was to send Interior Minister General Kafougouna Kona north to open talks with the rebels. General Kona has experience in negotiating with the Tuareg and is trusted by President Touré (BBC, October 17).

According to some reports, Qaddafi offered the Tuareg their own Sahelian/Saharan state to secure their loyalty (al-Jazeera, September 28; El Watan [Algiers], October 20). Only days before his resignation, Dr. Mahmud Jibril, the chairman of the Executive Bureau of the Libyan TNC, suggested that Mu’ammar Qaddafi was planning to use the Tuareg tribes to fight his way back into power, adding that the late Libyan leader was constantly on the move in Tuareg territories in southern Libya, northern Niger and southern Algeria. Rather bizarrely, Jibril then claimed that Qaddafi’s operatives in Darfur were raising a force of 10,000 to 15,000 Rashaydah tribesmen from Sudan (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, October 19). The Rashaydah are an Arab tribe found in the Arabian Peninsula, but also in Eritrea and the Eastern Province of Sudan, where they moved in large numbers in the mid-19th century. In general the Rashaydah remain aloof from local politics, preferring to focus on their camel herds. Jibril’s suggestion that large numbers of Rashaydah tribesmen could be rallied to Qaddafi’s cause seems strange and highly unlikely.

Arms Smuggling and Drug Trafficking

The Tamanrasset-based Joint Operational Military Committee, created by the intelligence services of Algeria, Mali, Niger and Mauritania in 2010 to provide a joint response to border security and terrorism issues, has turned its attention to trying to control the outflow of arms from Libya (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, July 8, 2010). The committee, which got off to a slow start, has announced its “first success”; identifying 26 arms traffickers and issuing warrants for their arrest (Jeune Afrique, October 14; L’Essor [Bamako], October 6). The list includes a number of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) commanders and is based on an investigation that discovered three major networks for smuggling arms out of Libya, the “most dangerous” consisting of Chadians and Libyans (Sahara Media [Nouakchott], October 8).

Security sources in the Sahel are reporting that AQIM is expanding its operations into the very lucrative business of people-smuggling by setting up an elaborate network that has the added advantage of allowing AQIM operatives to infiltrate into Europe (Info Matin [Bamako], October 6).

Drug trafficking continues to be another destabilizing factor in northern Mali as well-armed gangs battle over the lucrative trade. In early September at least five gunmen were killed in a battle between Tuareg traffickers and Reguibat Arabs with ties to the Saharawi Polisario Front. The battle ensued after the Tuareg kidnapped three Reguibat, including a senior Polisario officer, Major Harane Ould Zouida (Jeune Afrique, September 20). Such incidents are far from unknown in today’s Sahara; in January a major battle was fought between Bérabiche Arabs running drugs to Libya and Tuareg demanding a fee for passing through their territory (El Watan [Algiers], January 4; see also Terrorism Monitor, January 14). In this environment, drug traffickers are likely to be offering premium prices for military hardware finding its way out of Libya.

Traditional authority is now being challenged in both the Arab and Tuareg communities of northern Mali as AQIM, smugglers, rebel leaders and traffickers compete for the loyalty of young men in a severely underdeveloped region. The “noble” clans of the Arab and Tuareg communities have also suffered electoral defeats at the hands of “vassal” clans, a development the former blame on the vassal candidates buying votes with smuggling money (U.S. Embassy Bamako cable, February 1, 2010, as published in the Guardian, December 14, 2010; Le Monde, December 22, 2010; MaliKounda.com, December 7, 2009). The rivalry has spilled over into a contest for control of trafficking and smuggling networks. Ex-fighters of the Sahrawi Polisario Front (currently confined to camps in southern Algeria) have also entered the struggle for dominance in cross-Saharan drug smuggling. Members of Venezuelan, Spanish, Portuguese and Colombian drug cartels engage in frequently bloody competition in Bamako that rarely attracts the attention of the police (El Watan [Algiers], January 3).

A Tuareg Member of Parliament from the Kidal Region, Deyti ag Sidimo, has been charged by Algeria with involvement in arms and drug trafficking. The MP may be extradited to Algeria if his parliamentary immunity is lifted (Info Matin [Bamako], October 13; Le Combat [Bamako], October 4; Jeune Afrique, October 9-15).

Attack on the Abeibara Barracks

An example of the government’s inability to secure the Kidal region of north Mali was presented on October 2, when gunmen arrived at the site of a military barracks under construction in Abeibara. The gunmen sent the workers away with a warning not to return under pain of death before blowing up the construction materials. A National Guard unit tasked with protecting the work was apparently absent at the time of the attack. Military officials admitted that they did not know if the gunmen were AQIM, soldiers just returned from Libya or part of a criminal gang involved in the trafficking the construction of the barracks was meant to prevent (Info Matin [Bamako], October 26; AFP, October 3). It has also been suggested the attack was the work of local companies that had been outbid on the construction contract (Le Prétoire [Bamako], October 5). Fifteen soldiers were killed when a military garrison at Abeibara was attacked by a Tuareg rebel group under Ibrahim ag Bahanga in 2008 (Reuters, May 23, 2008).

Burned-out AQIM vehicle in the Wagadou Forest

Mauritanian Raid in Mali’s Wagadou Forest

Mauritanian jets carried out air strikes on October 20 on AQIM forces gathered in the Wagadou Forest (60 miles south of the Mali-Mauritania border), allegedly destroying two vehicles loaded with explosives (L’Agence Mauritanienne d’Information [AMI – Nouakchott], October 20; AFP, October 22). The Mauritanians appear to have hit their primary target, AQIM commander Tayyib Ould Sid Ali, who was on board one of the vehicles destroyed in the air strike. Mauritanian officials confirmed his death, saying Sid Ali was preparing new terrorist attacks in Mauritania after having been active in the region since 2007 (Ennahar [Algiers], October 22). The precision of the attack in difficult terrain suggested that Nouakchott had received accurate intelligence information regarding Sid Ali’s location. Mauritania’s security services had disrupted a Sid Ali-planned attempt to assassinate Mauritanian president Muhammad Ould Abdel Aziz in Nouakchott in February by intercepting AQIM vehicles after they crossed the border (Quotidien Nouakchott, February 3; see also Terrorism Monitor Brief, February 10).

Mauritania’s aggressive French-backed approach to the elimination of AQIM has seen several Mauritanian military incursions into Mali in the last year, including a previous ground assault on an AQIM camp in the Wagadou Forest in June that killed 15 militants and destroyed a number of anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons possibly obtained from looted Libyan armories (Sahara Media [Nouakchott], June 25; AFP, June 26; see also Terrorism Monitor Brief, July 7). Mali’s military has played only a minimal role in these operations and questions have been raised in Bamako regarding the government’s prior knowledge of these events and the military’s relative lack of participation.

2012 Elections

With the second term of Amadou Toumani Touré’s presidency coming to an end, national elections will determine a new government for Mali in Spring 2012. Though at least 20 individuals are expected to run for president, the contest is expected to be fought hardly between three prominent candidates, Dioncounda Traore, Soumaila Cisse and Ibrahim Boubacar Keita.

Mali’s Islamists see a political opportunity in the coming elections, with noted religious leaders Cherif Ousmane Madani Haidara and Imam Mahmoud Dicko making it clear Islamist groups will be involved (L’Indépendant [Bamako], September 29).

Reshaping the Rebellion

Three factors have redrawn the shape and ambition of the simmering rebellion in northern Mali in the last few months:

- The arrival in northern Mali (and neighboring Niger) of hundreds of experienced Tuareg combat veterans with enough weapons and ammunition to sustain an extended and possibly successful rebellion against a weak national defense force.

- The death of the controversial rebel leader Ibrahim ag Bahanga has removed a powerful but often divisive force in the Tuareg rebel leadership. This has opened space for the development of new coalitions and the emergence of new leaders with a broader base of support.

- The July declaration of independence by South Sudan has provided the lesson that a determined and sustained rebellion can overcome internal divisions and foreign opposition to arrive at eventual independence, even if secession means leaving with valuable resources such as oil or uranium.

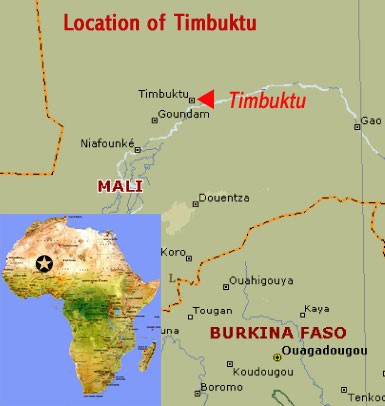

On October 16 the Mouvement National de l’Azawad (MNA) announced its merger with the Mouvement Touareg du Nord Mali (MTNM), led until recently by the late Ibrahim ag Bahanga (mnamov.net, October 17). The resulting Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) stated its intention to use “all means necessary” to end Mali’s “illegal occupation” of “Azawad” if the Bamako government does not open negotiations before November 5. Azawad is the name used by the Tuareg for their traditional territory in the Sahel/Sahara region north of Timbuktu. The term can also include traditional Tuareg lands in northern Niger and southern Algeria. The MNLA spokesman, veteran rebel Hama ag Sid’Ahmed, (former father-in-law of Ibrahim ag Bahanga) said that a number of high-ranking officers from the Libyan military had joined the group (BBC, October 17; Proces-Verbal [Bamako], October 17).

Two other groups have emerged since the return of the fighters from Libya with the stated intent of achieving autonomy for “Azawad.” The first is the Front Démocratique pour l’Autonomie Politique de l’Azawad (FDAPA), which includes veterans of the struggle for Bani Walid under the command of Colonel Awanz ag Amakadaye, a Malian Tuareg who served as a high-ranking officer in the regular Libyan Army (Kidal.Info, October 18; AFP, October 12; MaliWeb, October 25). The other group is an Arab “political and military movement” called the Front Patriotique Arabe de l’Azawad (FPAA). The group appears to be a kind of successor to the Front Islamique Arabe de l’Azawad (FIAA), an earlier expression of Arab militancy in northern Mali. Like the Tuareg, the Arab nomads of northern Mali have in the past suffered attacks from Songhai tribal militias such as the Mouvement Patriotique Ganda Koy (“Masters of the Land,” founded by Mohamed N’Tissa Maiga), which advocated the extermination of the nomadic Arabs and Tuareg of Mali (see interview with Maiga – Le Politicien [Bamako], July 21). These assaults played a large role in initiating the Tuareg and Arab rebellions of the 1990s and there have been calls in certain quarters of Mali for a revival of the Ganda Koy (Le Tambour [Bamako], November 25, 2008; Nouvelle Liberation [Bamako], November 19, 2008).

Conclusion

Mali is experiencing its own “blowback” as a result of its support for the Qaddafi regime in Libya. No effort was made to prevent Malian Tuareg from joining Qaddafi’s forces; indeed, the government even granted leave of absences to Tuareg officers who wished to fight in Libya. Bamako’s thinking no doubt went along the lines of believing that such assistance might help preserve the ever-generous Qaddafi regime; if, on the other hand, things did not go well for the Libyan regime, Bamako could at least count on the loss of a number of troublemakers and officers of uncertain loyalty. What was likely not anticipated was the return of hundreds of well-trained and well-armed Tuareg military professionals, some of whom have been absent from Mali for decades, along with most of the more recent pro-Qaddafi volunteers. Mali is suddenly faced with the possible existence of a professional insurgent force that needs only to fight a war of mobility on its own turf, territory that has often proved disastrous for a Malian military composed mostly of southerners with little or no experience of desert conditions and tactics. If another round of Tuareg rebellion breaks out in Mali, the security forces will be hard pressed to deal with it, leaving ample space and opportunity for AQIM to expand its influence and power at the expense of the Malian state.

This article first appeared in the October 28, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor