Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, July 29, 2017

After an eight year hunt for Boko Haram leader Abu Bakr Shekau, Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff, Lieutenant General Tukur Yusufu Buratai, has placed one of the nation’s top generals in an uncomfortable spot by issuing him a forty-day deadline to apprehend Shekau, dead or alive.

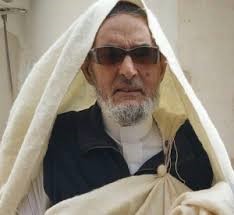

Major General Ibrahim Attahiru

Major General Ibrahim Attahiru

The Man and the Mission

The order was given on July 21 to Major General Ibrahim Attahiru, the Theatre commander in northeast Nigeria and leader of the anti-Boko Haram Operation “Lafiya Dole.” [1]

As commanding officer of the Nigerian Army’s 82nd Division, Attahiru directed Operation Crocodile Smile, a joint forces amphibious operation launched against militants in the Niger Delta on August 29, 2016. Attahiru declared the operation a success at its close in mid-September, having killed 23 militants and carrying out the destruction of 38 camps and 91 illegal oil refineries. Army losses included four drowned and one victim of militant fire (Today [Lagos], September 18, 2016). [2] General Attahiru was the Director of Administration Defence Headquarters when appointed to the Borno theatre.

Attahiru and Operation Lafiya Dole

Attahiru took command of the North-East Theatre and Operation Lafiya Dole in May 2017 after a surprise shakeup of leading Nigerian Army commanders. Attahiru replaced Major General Lucky Irabor, who had served 14 months in the post and had the confidence of many of his officers despite repeated and unfulfilled predictions of an imminent Boko Haram collapse. Irabor was posted as the new Force Commander of the Multi-national Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a regional effort to combat Boko Haram with its headquarters in N’Djamena.

During the command turnover, General Irabor claimed that the Army had taken 1400 suspected members of Boko Haram prisoner in recent months. At the same ceremony, Attahiru promised the opening of a divisional human rights desk where misconduct by officers and troops could be reported (Today [Lagos], May 30, 2017; Vanguard [Lagos], May 30, 2017). Assertions of human rights abuses during the conflict in Borno have frequently impeded the progress of the military and may even have aided recruitment by Boko Haram.

Burning Villages, Operation Lafiya Dole

Burning Villages, Operation Lafiya Dole

The first test of this new approach came days later, following a Boko Haram attack on the village of Ali Dawari (near Maiduguri) on June 7. Villagers fled the attack, but when they returned they claimed to have witnessed Nigerian troops (who had arrived in the meantime) loading their personal effects and foodstuffs onto three military trucks before setting fire to the village. Attahiru dismissed the entire incident: “No soldier would do such a thing. Our troops are guided by rules of engagement and they won’t descend to the level of doing what the people are alleging. On the contrary, the Boko Haram terrorists perpetrated such atrocities and not our troops” (Today [Lagos], June 13, 2017).

The Nigerian Army is processing selected Boko Haram detainees through “Operation Safe Corridor,” a de-radicalization and rehabilitation process designed to enable the former insurgents to “positively reorient their views about life and society in general.” [3] Few details of how this is accomplished are available.

The Shekau Resurgence

According to figures provided by General Attahiru, Boko Haram should now be in its death throes. On July 6, Attahiru told reporters that 404 terrorists had been killed and another 800 to 1000 captured in the last four months alone against a loss of 15 soldiers. However, the general also admitted to 97 suicide bombings and vehicle-borne bombings in the same time span (Today [Lagos], July 7; July 9, 2017).

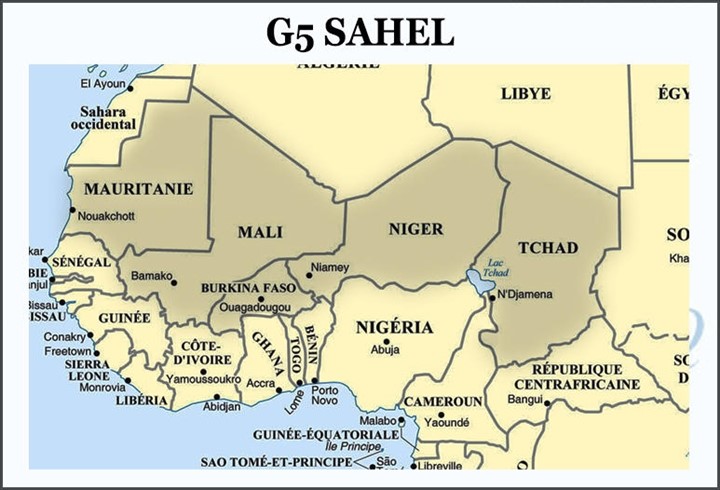

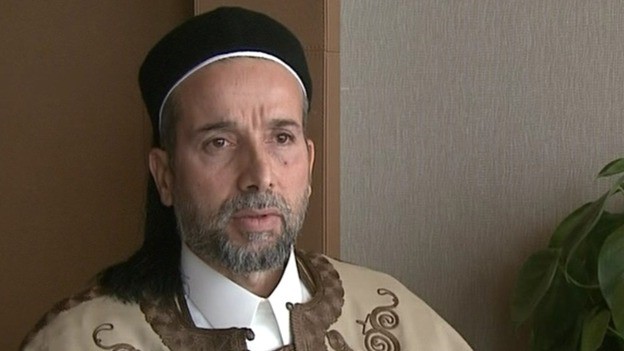

Rather than disappearing, Shekau has made repeated video appearances in which he threatens his opponents – in March he insisted his movement would not stand down until it had been established in Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Nigeria, Niger and Mali (Premium Times [Lagos], March 17, 2017).

On March 28, Nigerian defense minister Mansur Dan-Ali admitted that Shekau was still alive and justified the prolonged eight-year search for Shekau by noting: “It took America about seven to 10 years to get Bin Laden so we will get Shekau as soon as possible.” Following years of government claims that Shekau was dead, the minister now claimed that it was Boko Haram that was trying to give the impression he had been killed so the Army would relax its efforts (Daily Times [Lagos], March 29, 2017).

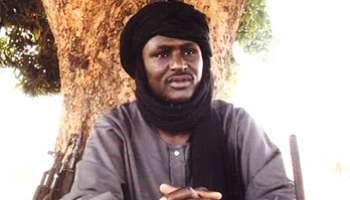

A 33-minute video released in June depicted Shekau describing an attack by his followers on a military outpost outside of Maiduguri while displaying ammunition and military gear seized in the assault. Shekau scorned the Army’s operations in the Sambisi forest, claiming his group had already moved to a site near Maiduguri and mocked the military’s repeated claims that he was either dead or replaced by a double: “So I’m alive. But if God wills that you will kill me, it is not surprising because many prophets of Allah were killed by infidels” (Today [Lagos], July 21, 2017).

The Boko Haram leader’s latest video, released on June 28, asserted “There is no way we Muslims in mosques and Christians in churches can work together. This has never happened before even during the life time of apostles and prophets.” According to Shekau, Nigeria’s constitution and democracy prevents any type of dialogue between Muslims and Christians. He issued a warning to Nigeria’s Muslim clerics that they were “playing with hell-fire” by “giving wrong interpretations of the Holy Quran” (Vanguard [Lagos], June 28).

Shekau also claimed credit for the Damboa road ambush a week earlier, saying ten policewomen had been captured who God had given to the insurgents to be their “slaves.” He ended his message by calling on Nigerians to “work for Islam, in accordance with the caliphate that was established by ‘Uthman Dan Fodio, which is a caliphate built upon truth and belief in God” (Vanguard [Lagos], June 28, 2017). Shekau’s reference was to the 19th century Sokoto Caliphate established by the Fulani Islamic scholar ‘Uthman Dan Fodio, a frequent ideological touchstone for jihadists operating in the Sahel. The Caliphate was known for its reliance on slave labor – Shekau’s boast implies that a revival of slavery is part of the Islamists’ program.

Boko Haram vs. Oil Exploration

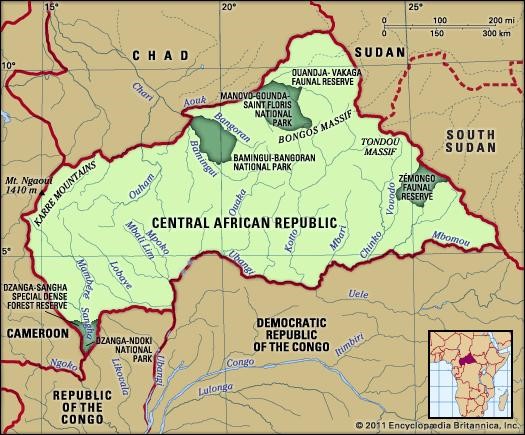

Though there are indeed fears that Boko Haram may be scattering; it appears to still have a strong hold on parts of the Sambisi forest, the group’s traditional refuge. On July 26, an Army statement announced that a lieutenant and nine soldiers of the Army’s 5th Brigade had been killed the day before after a convoy escorting Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) workers came under heavy fire in the forest from Boko Haram militants. A number of other soldiers were missing (Sahara Reporters, July 26, 2017). A statement by a Nigerian Army spokesman claimed that all NNPC staff had been rescued while troops were busy “neutralizing” terrorists and pursuing them “relentlessly.”

Two days later, more independent sources were reporting over 50 dead “with more bodies coming in.” The bodies of 18 soldiers and 30 others were brought back to Maidguri after the attack in an area near Lake Chad. Many of the civilians were members of the so-called “Civilian JTF,” a vigilante group that works alongside Nigerian military forces, though their amateur status often leads to heavy casualties in confrontations with the more experienced Boko Haram.

In contrast to the Army’s claim that all oil personnel had been rescued, Minister of State of Petroleum Resources Ibe Kachikwu told journalists that he could not confirm that any NNPC staff had been rescued (The Cable [Lagos], July 28, 2017). A day later, a video emerged of three kidnapped NNPC members in Boko Haram hands, begging the government to meet their captors’ demands. Their identities were confirmed by the Vice-Chancellor of Maiduguri University (to which they are attached) with the vice-chancellor also confirming the deaths of five other members of the university in the ambush (AFP, July 29, 2017).

The ambush was intended to disrupt oil exploration in the Borno region by targeting geological surveyors deployed there after having received assurances from the military that the region was now safe. Nigeria is looking to begin oil production in the northeast to relieve the pressure militants are putting on production in the Delta region, though the attack (so far attributed to al-Barnawi’s faction) demonstrates that the Army’s claims to have secured the region sufficiently to permit oil operations are largely illusionary.

Elsewhere, a video released by Boko Haram in early July showed members of the groups executing eight “apostates” who had defied the “Shari’a police” before cheering crowds. The video also showed other punishments inflicted by the group, including a stoning, a beheading, flogging and forced amputations (AFP, July 11, 2017).

Warnings that some elements of Boko Haram were relocating to the northern Nigerian city of Kano (the largest city of the former caliphate) appeared to be confirmed on July 23 when a well-equipped cell of five militants were arrested after a firefight there with Nigerian security forces. According to the Kano State police chief, the fighters had relocated to Kano from the Sambisi forest (AFP, July 24, 2017).

Nigerian Army Patrol, Operation Lafiya Dole

Nigerian Army Patrol, Operation Lafiya Dole

Boko Haram attacks intensified after the ill-advised release of a number of Boko Haram leaders from Nigerian prisons in May in exchange for the release of 82 of the “Chibok girls” kidnapped in 2014. The most common tactic used by Shekau’s group at present is road ambushes. Female suicide bombers are also still being deployed, though it is uncertain whether these originate with Shekau’s group or the Boko Haram faction led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi and Mamman al-Nur.

Conclusion

According to a Nigerian military memo, Boko Haram has begun re-occupying “Camp Zero,” their former main base in the Sambisi Forest. When the Nigerian Army took the base in December 2016, it was heralded as the beginning of the end for Boko Haram, and its capture continues to be frequently referred to in government and military statements as proof of the success of the campaign against the militants. However, the military appears to have withdrawn from the base in March, leaving it wide open to reoccupation by the Islamist gunmen (AFP, July 24, 2017).

There is one consistent aspect to the struggle in north-eastern Nigeria – the reality promulgated by Nigerian military spokesmen remains in conflict with the reality experienced by Nigerians in Borno State. Nigerian intelligence has had few successes in Borno, and with the military apparently unsure of whether Shekau is in Sambisi, Maiduguri or even Kano, it seems unrealistic to believe he will be apprehended “dead or alive” by the end of August. If the military did indeed have information regarding Shekau’s whereabouts, a more clandestine approach would seem to be called for. Instead, the Army has jeopardized the career of one of its leading officers by imposing a short and arbitrary date for the end of the hunt for Nigeria’s most elusive individual. That the order came with a public plea for information regarding Shekau’s whereabouts inspires little confidence.

Worst of all, there may actually be little encouragement behind the scenes to bring Shekau in alive or even at all. Continued destabilization of the north has been treated as a political advantage by many Nigerian politicians. [4] Even if Shekau (who needs only to remain hidden for a month to score a major propaganda coup) is somehow disposed of, the equally, if not stronger, al-Barnawi-Mamman al-Nur faction of Boko Haram will remain at large. Ultimately, the forty-day deadline appears to be little more than an ill-considered political publicity stunt carried out at the expense of a professional soldier.

Notes

- Nigerian Army Press Release, “Chief of Army Staff Gives Theatre Command Operation Lafiya Dole Deadline to Capture Abubakar Shekau,” July 22, 2017, http://www.army.mil.ng/chief-of-army-staff-gives-theatre-command-operation-lafiya-dole-deadline-to-capture-abubakar-shekau/

- For Operation Crocodile Smile, see: “Nigeria Expands Its ‘War on Terrorism’ to the Niger Delta,” Terrorism Monitor, September 16, 2016, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3719.

- Nigerian Army Press Release: “Boko Haram… 43 Surrendered Insurgents Air Lifted for De-Radicalization,” July 24, 2017, http://www.army.mil.ng/press-release-boko-haram-43-surrendered-insurgents-air-lifted-for-de-radicalization/

- For the political uses of Islamist violence in northern Nigeria, see: “Political Violence and Islamist Militancy become Entwined in Maiduguri Bombing,” January 25, 2014, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=793.