Andrew McGregor

Jamestown Foundation Special Commentary on Libya

April 20, 2011

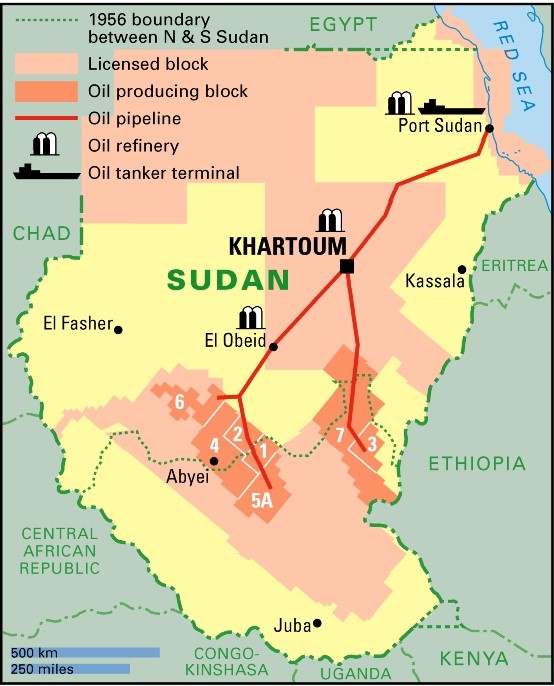

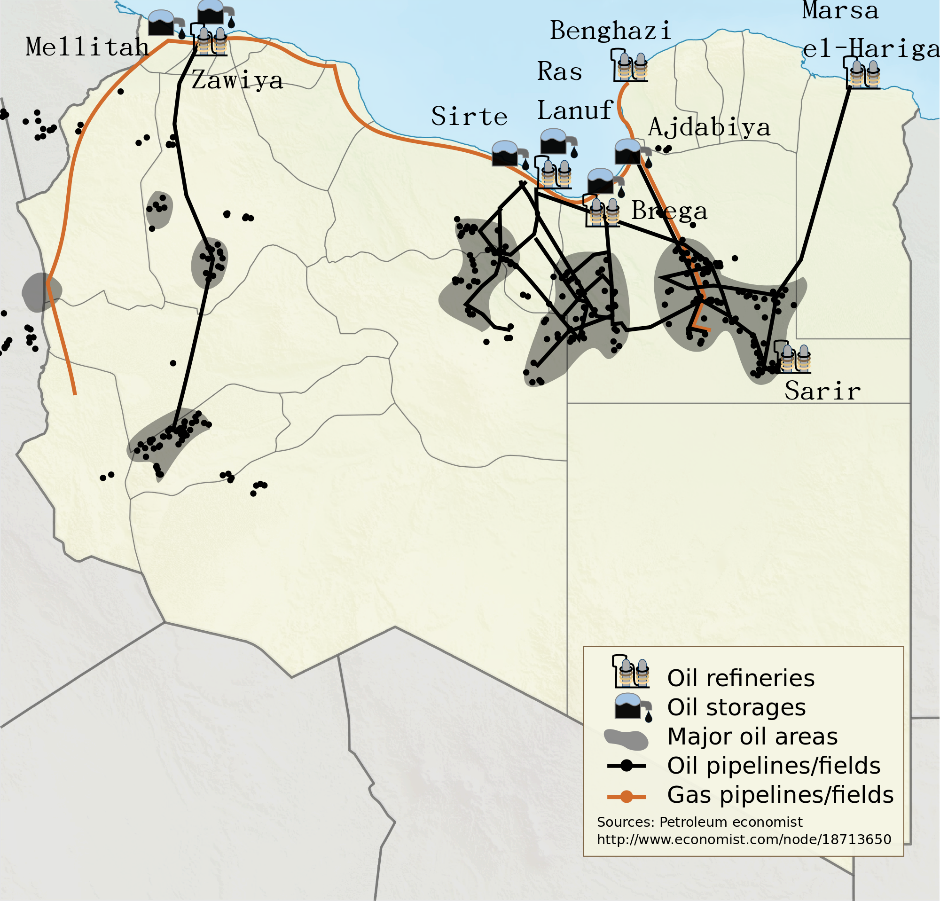

Executive Summary: After nearly two months of fighting in Libya, what began as a revolution against Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s repressive regime has turned into an internal and international struggle for control over Libya’s oil and gas reserves. Of the country’s four major oil basins, the most productive – Sirte Basin – is only partly controlled by the rebel forces. While some reserves are in contested areas, the majority of Libya’s oil is still in government hands. Now lacking funds, arms and leaders, the rebels’ sole asset and the key to any possible success is their share of the oil fields. They are currently desperate for funds, fuel and training. Furthermore, the rebels are almost completely dependent on NATO forces to defend their oil operations, which would require the unpopular and unlikely decision to put Western troops on the ground in Libya. However, multiple American energy producers, including ConocoPhillips, hold stakes in Libyan oil fields. The international community is now scrambling to find alternative sources of oil until UN sanctions are lifted. Qatar, which has supplied the Benghazi rebels with four shipments of petroleum products, has also agreed to market the rebel oil. Additionally, Saudi Arabia has boosted its output to meet any shortfall in supply created by the Libyan crisis. Meanwhile, the violence in this oil war is spreading, with three oil workers recently killed in loyalist attacks on the Misla and Sarir oil fields in early April.

Executive Summary: After nearly two months of fighting in Libya, what began as a revolution against Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s repressive regime has turned into an internal and international struggle for control over Libya’s oil and gas reserves. Of the country’s four major oil basins, the most productive – Sirte Basin – is only partly controlled by the rebel forces. While some reserves are in contested areas, the majority of Libya’s oil is still in government hands. Now lacking funds, arms and leaders, the rebels’ sole asset and the key to any possible success is their share of the oil fields. They are currently desperate for funds, fuel and training. Furthermore, the rebels are almost completely dependent on NATO forces to defend their oil operations, which would require the unpopular and unlikely decision to put Western troops on the ground in Libya. However, multiple American energy producers, including ConocoPhillips, hold stakes in Libyan oil fields. The international community is now scrambling to find alternative sources of oil until UN sanctions are lifted. Qatar, which has supplied the Benghazi rebels with four shipments of petroleum products, has also agreed to market the rebel oil. Additionally, Saudi Arabia has boosted its output to meet any shortfall in supply created by the Libyan crisis. Meanwhile, the violence in this oil war is spreading, with three oil workers recently killed in loyalist attacks on the Misla and Sarir oil fields in early April.

Introduction

As ships of the U.S., French and British fleets stood by, a supertanker carrying a Libyan rebel shipment of 550,000 barrels of high-grade crude oil worth $110 million made its way from Tobruk earlier this month, headed east for China. An observer might have come to the conclusion that the war in Libya was securing the energy supplies of those who refused to sanction or join it. Without knowing it, however, this observer could also have been gazing at the last major oil shipment to leave Libya for some time, leaving a revolution the West had hoped would be self-financing instead reliant on handouts from nations that have invested too much in the revolt to turn back.

Assertions that oil was behind the conflict from the beginning are both predictable and inaccurate. The West had repaired its relations with Qaddafi who was opening the Libyan oil industry to Western participation and was selling the West prime petroleum products at market rates. There was simply no reason to destroy stability in a reliable energy producer, particularly at a time when the United States and its allies are trying to disengage from two costly wars in Muslim countries and mount their own economic recoveries.

The Libyan revolt was rather a spontaneous eruption of dissatisfaction with Qaddafi’s repressive and erratic regime. This, however, has been its greatest weakness; the revolt is unorganized, unplanned, unfunded, leaderless and militarily inferior to its opponent. Despite a month of fighting, international sanctions and a massive Western aerial intervention, the revolt that began with the slogan “Libyans can do it themselves” is now desperate for funds, fuel, food, arms and training. The rebels’ sole asset and the key to any possible success is the oil fields under their control, though recent long-range operations by Qaddafi loyalists in the Libyan desert have halted production, leaving the rebels without a source of financing and entirely dependent on Western sources of money and arms, a long way from the revolution’s once buoyant “do it ourselves” philosophy. It did not start this way, but the Libyan crisis has evolved into an internal and international struggle for control of Libya’s abundant oil and gas reserves.

Libyan Oil Production

Libya is home to four major oil basins: the Ghadames, Murzuk, Kufra and Sirte basins. The most productive is the 230,000 km² Sirte Basin, which holds roughly 80% of Libya’s proven reserves with 43 billion barrels and accounts for 90% of production. The rebels control a part of the Sirte Basin capable of producing 200,000 bpd. Some reserves are in contested areas, but the vast majority of Libya’s oil remains in government hands. While fuel supplies have been a problem in the rebel-held areas, the government continues to control nearly all Libya’s refining capacity and most of its export terminals (Reuters, April 11). Libya has the largest oil reserves in Africa and is the world’s 17th largest oil producer. 85% of production goes to Europe, 5% to the United States and 10% to China.

The rebel-held oil facilities are now being operated by AGOCO (Arabian Gulf Oil Company), a 1979 split-off from the state-owned National Oil Corporation (NOC). AGOCO claims it has two million barrels still in storage at Marsa al-Hariqa, though this has not been confirmed (Reuters, April 7). The NOC claims it is currently producing up to 300,000 bpd, but would have little alternative to storing production until sanctions are lifted or alternative means of sale can be established.

Besides agreeing to market the rebel oil, Qatar has also supplied the Benghazi rebels with four shipments of badly needed petroleum products through its state owned International Petroleum Marketing Co. (PennEnergy, April 13).

Saudi Oil Minister Ali al-Nuaimi said Saudi Arabia has enough spare output capacity to meet any shortfall in supply created by the Libyan crisis, having already boosted its output to about nine million bpd, including a new blend it claims approximates light sweet Libyan crude (Gulf Daily News [Bahrain], April 10). However, Saudi Arabia has not produced more than 10 million bpd in recent years and some industry experts doubt it will be able to increase production to 12.5 million bpd, as it claims. There are also questions regarding the quality of the new Saudi blend, which may not be as fine as the Libyan product.

Opportunities for China and Russia?

Defected former Libyan Energy Minister Omar Fati bin Shatvan recently declared that Russia and China would not be granted the opportunity to develop oil and gas fields in Libya under a new rebel regime because they had failed to support the rebellion, adding that French and Italian companies could be rewarded with oil and gas contracts for their support (AFP, April 7). However, Qaddafi has already invited Russian, Chinese and Indian diplomats to discuss taking over Western oil operations in Libya once he has dealt with the Western supported rebellion.

Vulnerability to Attack

Three oil workers were killed in loyalist attacks by armored vehicles on the Misla oil field on April 4 and 5, and an attack on the Sarir oil field on April 6. Sarir is also home to important installations belonging to the $25 billion Great Man-Made River project, which supplies water from subterranean Saharan aquifers to Libya’s cities, including Ajdabiyah and Benghazi.

Tripoli claimed (without evidence) that the damage was caused by “British war planes,” perhaps seeking a propaganda victory on top of a series of successful raids (UKPA, April 7). The rebels are calling for NATO to defend their oil operations, but this will be difficult without putting Western troops on the ground, a move that would be opposed by many NATO members. Loyalist forces seem to be basing their attacks out of the Waha oil field, located near the center of the Sirte Basin operations. American energy producer ConocoPhillips has a 16% share in a joint venture working the Waha oil field, while Marathon Oil and Hess Corporation hold smaller stakes. Qaddafi’s forces can also operate from the desert city of Sabha, home to a large military base and the loyalist Megarha tribe, striking east to attack rebel-held oil fields.

The loyalist raids targeted oil storage tanks and a diesel tank that provides fuel to the generators at Misla and Sarir. Many skilled workers capable of repairing such damage have been evacuated from Libya and the rebels have only been able to spare young, untrained fighters to defend the oilfields from further destruction (Financial Times, April 7). Without more substantial defenses, it looks like rebel oil production will cease for the duration of the conflict. Even before the attacks, oil production at the Misla and Sarir oil fields was only one-third of capacity. AGOCO officials have said production will not resume until the oil fields have been secured (Reuters, April 13). In these circumstances, Qaddafi’s forces can continue to disrupt rebel oil operations without having to damage or destroy the most important elements of the oil fields, enabling them to be put back into production quickly in the event of a loyalist victory.

The loyalist raids targeted oil storage tanks and a diesel tank that provides fuel to the generators at Misla and Sarir. Many skilled workers capable of repairing such damage have been evacuated from Libya and the rebels have only been able to spare young, untrained fighters to defend the oilfields from further destruction (Financial Times, April 7). Without more substantial defenses, it looks like rebel oil production will cease for the duration of the conflict. Even before the attacks, oil production at the Misla and Sarir oil fields was only one-third of capacity. AGOCO officials have said production will not resume until the oil fields have been secured (Reuters, April 13). In these circumstances, Qaddafi’s forces can continue to disrupt rebel oil operations without having to damage or destroy the most important elements of the oil fields, enabling them to be put back into production quickly in the event of a loyalist victory.

The only export terminal in rebel hands is Marsa al-Hariqa near Tobruk, which would be vulnerable to attack via the desert highway from Ajdabiyah should that city be secured by loyalist forces. Marsa al-Hariqa is the smallest of Libya’s oil terminals in terms of loading volumes. Perhaps the most vulnerable part of the infrastructure is the 500 km pipeline connecting the eastern oil fields to Marsa al-Hariqa. Other pipelines connect the same oil fields to terminals controlled by the government.

An Unfinanced Revolution

The rebel leadership is attempting to secure an exemption from UN sanctions for their oil exports. However, even if loyalist forces are ousted from the oil fields, it is likely the rebels will be unable to produce more than about 50,000 bpd, an amount likely to be insufficient to finance services, purchase food and other goods and run an expensive military campaign against Qaddafi’s forces. Marine insurance for vessels doing business in Libya has skyrocketed, perhaps prohibitively except for countries such as Qatar that are willing to absorb the risk. UK Foreign Secretary William Hague has already asked the international community to provide “temporary” financial support to the INC. Qaddafi has considerable gold reserves stored in Tripoli, enough to keep a war running for years, while the rebels have only whatever oil is still stored at the Tobruk terminal.

In the continuing search for funds, the rebel Interim National Council (INC), recognized as Libya’s government by France, Italy and Qatar, has asked the United States for immediate access to Qaddafi’s frozen assets, believed to total more than $34 billion (Reuters, April 9). The request raises the question of whether funds that should belong to the Libyan people as a whole can be released to an unelected committee composed largely of Benghazi-based dissidents.

Stalemate or Defeat?

Without military intervention by ground forces, indicators point not toward stalemate, but toward an eventual government victory, even if NATO airstrikes cause a delay in this outcome. Strategically, Qaddafi’s forces hold the upper hand and have proven highly adaptable in developing tactics to cope with NATO’s aerial intervention.

Qaddafi is demonstrating that authoritarianism will prevail over the type of “war by committee” that is being run by both NATO and the Libyan rebels. The no-fly zone might actually have improved loyalist tactics, forcing them to abandon slow moving armor columns in favor of more mobile deployments in pick-up trucks that are able to mount quick strikes against rebel forces. U.S. and NATO commanders complain that loyalist forces assemble near civilian infrastructure such as schools and hospitals as if this was somehow “unfair.” The West has invented this form of limited warfare and should not be surprised that the Libyans and others subjected to it would devise tactical methods of response that do not involve lining up in the open desert to be destroyed by enemy airstrikes.

With many major tribes now siding with Qaddafi, whether through loyalty, tribal ties or cash payments, NATO stands in danger of being seen to be attempting to impose a national government consisting of a dissident minority. Such a state would seem to stand little chance of survival once NATO military support is withdrawn. Both sides have broken out the armories, and Libya is now flooded with arms, leaving any new government subject to armed opposition.

Having taken the lead in marketing rebel oil, the tiny emirate of Qatar appears to be taking the lead in arming the insurgents – according to rebel General Abd al-Fatah Younes (who appears to have picked up a Western security team to ensure his personal safety), Qatar has supplied the rebel forces with anti-tank weapons (al-Jazeera, April 8; Independent, April 7). Considering the military ineptness of rebel forces prone to panic and flight, there is every possibility that arms and munitions provided to the rebels will soon wind up in the hands of a grateful loyalist army.

Conclusion

NATO’s campaign might easily be called “The War of Contradictions,” since it has said one thing and done another from the beginning. Its entire framework for intervention is based on a no-fly zone to protect civilians that was exposed as a cover for battlefield air support for the Libyan rebels almost immediately. While some NATO nations see the campaign as one intended to protect civilians, France, Britain and the United States are clearly set on regime change, a course that cannot be reversed at this point. From the beginning, Western involvement in the Libyan crisis has been based on the false assumption that Qaddafi was universally disliked and unwanted in Libya. Despite ample evidence to the contrary after nearly two months of fighting, the NATO campaign continues to rest on this unfounded belief.

NATO and the Western media celebrate every time another non-combatant politician defects, but these efforts at self-preservation play no role in the battle on the ground. What is more important is the near total absence of defecting loyalist fighters. For the Libyan regulars and their mercenary auxiliaries it is clear who has the upper hand in the fighting and who has the ability to pay their troops and reward success handsomely.

Rebels now demand nothing less than unconditional surrender – probably not a realistic option, but one based on the belief that NATO will do their fighting for them. The rebels now believe their ranks to be thoroughly infiltrated by Qaddafi spies, probably a sign that morale is crumbling as rebel fighters refuse to acknowledge war is a professional’s game.

If the conflict drags on, who will be the first to break sanctions by buying oil from the Qaddafi government? Italian oil firm Eni was reported to be arranging for a shipment from a Qaddafi-controlled terminal, but believes the shipment will not violate sanctions as the oil is owned by Eni (Reuters, April 13). Italy purchases 32% of Libya’s oil and must now try to make up the shortfall.

Without oil, the rebel movement has no future. It already lacks ideology and a leader; if it also lacks a financial base it would seem to have little future. As one rebel fighter told a Reuters correspondent: “We have no coordination. We have no organization. We really have no strategy. We have no commander” (Reuters, April 10). To succeed in destroying the rebellion, Colonel Qaddafi must prevent the rebels from producing and selling oil. If the conflict drags on, the costs to Western nations involved in imposing a naval blockade, maintaining a no-fly zone, providing air support to rebel operations and funding, feeding and fueling the “liberated” areas of Libya will soon draw an outcry from the very same public that once demanded military intervention. Time is on Qaddafi’s side; eventually international pressure will force the rebels to temper their demands to find a negotiated settlement. The alternative is Western military occupation of Libya, a new and unexpected war to be added to the unresolved campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.