Andrew McGregor

January 25, 2014

Despite living in the midst of some of the world’s most open and sparsely populated spaces, Libya’s southern tribes are engaged in a new round of bitter urban warfare, as snipers, gun-battles and mortar fire take a heavy toll on the civilian population. At stake are control over the abundant resources of the Libyan south, the heavy traffic of its trade routes (both licit and illicit) and the future of tribal and ethnic relations in a post-Qaddafist south. Simultaneous with these disputes, however, is the mysterious and oddly-timed emergence of “Qaddafist supporters” waving green flags (the symbol of the Qaddafist revolution) in several different Libyan centers, most notably in the southern oasis settlement of Sabha, where they were alleged to have seized an airbase.

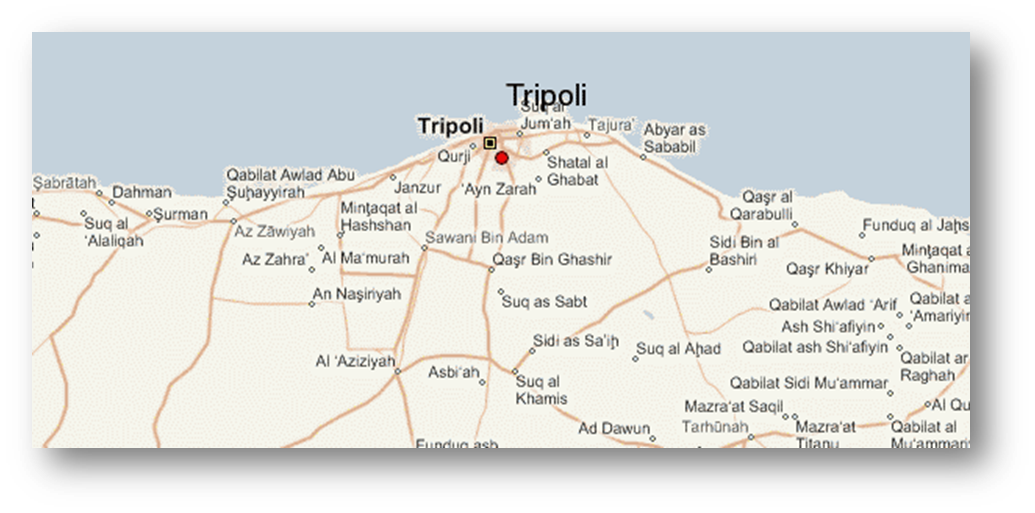

Central Sabha

Central Sabha

Sabha, the Strategic Hub of South-West Libya

Since late December, the strategic oasis city of Sabha has been the scene of deadly clashes between the Tubu, a tribe of indigenous Black African nomads ranging through the eastern Sahara, and the Awlad Sulayman, a traditionally nomadic Arab tribe of the Fezzan (southwestern Libya). Sabha, a city of 210,000 people about 400 miles south of Tripoli, is the site of an important military base and airfield. It also serves as a commercial and transportation hub for the Fezzan. Many of the residents are economic migrants from Niger, Chad and the Sudan, while the Qaddadfa (the tribe of Mu’ammar Qaddafi) and the Awlad Sulayman are among the more prominent Arab tribes found in Sabha. One of the last strongholds of the Qaddafi loyalists, Sabha was taken by revolutionary militias in September 2011. [1]

In March 2012, three days of vicious fighting in Sabha that began as a dispute between the Tubu and the Arab Abu Seif and morphed into a battle between the Tubu and the Awlad Sulayman left 40 Tubu and 30 Arabs dead. After a ceasefire ended the fighting by the end of the month, serious clashes erupted in Sabha once more on January 11. Tubu militants directed mortar fire into Sabha from the edge of town, targeting Awlad Sulayman neighborhoods. The street violence reached such a peak that the Sabha National Security Directorate admitted it no longer had the resources to even attempt to maintain law and order. The Sabha Local Council was forced to suspend operations in late December. On January 17, mortars struck the residence of Sabha’s military governor. The region is desperately short of medical supplies, a situation worsened by gunmen who stole part of an emergency shipment of medical supplies from the UAE and an attack on the Sabha hospital (Libya Herald, January 17; January 20).

It appears to have been fallout from this earlier struggle that sparked the latest clashes, as Tubu gunmen from Murzuk stormed a Traghen police station (140 kilometers south of Sabha) on January 9. The gunmen ignored a number of high value targets as they searched specifically for al-Haq Brigade leader Mansur al-Aswad, the deputy commander of the Sabha military zone. The brigade leader was eventually found and murdered, allegedly in retaliation for crimes committed by his Abu Seif militia during the 2012 clashes in Sabha (Libya Herald, January 10).

Both the Tubu and Zuwaya, rivals in Kufra, have communities in the coastal city of Ajdabiya, that city being the northern terminus of the trade routes that run through Kufra to the north. The conflict has traveled north through this route to Ajdabiya, where a Zuwaya unit under the command of the general staff has had deadly clashes with a Tubu unit under the command of the Defense Ministry (AFP, December 23, 2013).

Misrata’s 154 Battalion joined Libyan Army regulars heading to Sabha to restore order (Libya Herald, January 20). The Tubu arrived at reconciliation talks attended by several leading government ministers and a Zintani reconciliation committee with three demands they insisted be met before negotiations could continue:

- Establishing exactly who the Tubu were fighting (an issue complicated by the tendency of imported Arab militias to ally themselves with local Arab groups);

- The expulsion of Awlad Sulayman gunmen from local military compounds and the historic Elena castle (formerly known as Fortezza Margherita), an Italian colonial relic that still dominates Sabha;

- The transfer of the castle, still used for military purposes and detentions, to the Ministry of Tourism (Libya Herald, January 22).

The Sabha “Castle” – an Italian-era fortress

According to Isa Abd al-Majid Mansour, leader of the Tubu Front for the Salvation of Libya, the violence in the south is designed to eliminate the Tubu presence in Libya: “This is not a tribal war… The Islamist militias aided by the Libyan government want to get rid of us. International bodies that come to investigate will see who are the victims, with what arms and in which conditions they were shot. They will know that innocent people are taken from their homes and shot by 14.5mm caliber [weapons]” (Paris Match, January 20). Isa Abd al-Majid insists that Sabha has become a headquarters for al-Qaeda forces drawn from Libya, Algeria, Tunisia and Mauritania. (Paris Match, January 20).

The Mysterious Qaddafists

A group of “Qaddafists” were reported to have seized Tamenhint Air-base (30 kilometers east of Sabha) on January 18, relinquishing it after sorties by Libyan jet-fighters on January 19 to redeploy “with a large convoy” on the road between Sabha and Barak Shati, according to a Zintani mediator (Libya Herald, January 19). According to the spokesman for the Libyan defense ministry, the occupiers were Qaddafi supporters (al-Arabiya, January 18).

After the Qaddafists left, the base was occupied by Tubu troops of the Murzuk Military Council, though these withdrew on January 20 before the arrival of the Misrata militia, allowing the Qaddafists to reoccupy the facility. Defence Ministry spokesman Abdul-Raziq al-Shabahi said: “The situation in the south … opened a chance for some criminals … loyal to the Gaddafi regime to exploit this and to attack the Tamahind air force base” (Reuters, January 20). Libyan government sources claim the violence in the south is being orchestrated by Saadi Qaddafi, a son of the late dictator who has taken refuge in neighboring Niger.

Other pro-Qaddafi elements were said to have taken to the streets in Ajilat, waving green flags and carrying portraits of the late dictator. The Zintan militia was called in when local authorities were unable to contain the demonstrations and five alleged Qaddafi supporters supposedly on their way to Ajilat were killed in nearby Sabratha. Though authorities claimed to have arrested seven Qaddafists, they refused to release any information about the suspects (Libya Herald, January 22).

Oddly, there was also a manifestation of green-flag waving “Qaddafists” who tried to attack the Italian section of a non-Muslim cemetery in Tripoli. The group was driven off by locals, but have apparently returned at night twice to damage graves, even killing the night-watchman in their second visit. West of Zahra, other alleged Qaddafists were reported to have raised the green flag (Libya Herald, January 20).

The identity of the alleged Qaddafists remains in question. In Sabha, citizens became alarmed when reports began to circulate that the Qaddafists were actually “foreign troops from Chad,” prompting a formal Libyan government denial (Libya Herald, January 21).

Tubu Militiamen, Murzuk (Karlos Zurutuza/IPS)

Tubu Militiamen, Murzuk (Karlos Zurutuza/IPS)

Tubu militias have occupied two other important military bases in Libya’s largely ungoverned southwest, a refuge for smugglers and terrorists. Al-Wigh airbase was occupied by Colonel Barka Warduko’s Murzuk Desert Shield militia and the military post at al-Tum was occupied by the Oum al-Aranib militia commanded by Sharfadeen Barka.

Qaddafists have also been blamed for the violence in the Ajilat region (on Libya’s northwest coast), where a militia from Zawiya has been fighting with the Warshefana tribe, which has regularly been accused of pro-Qaddafist tendencies.

The neighboring groups have been fighting sporadically since the overthrow of Qaddafi, deploying weapons as large as Grad rockets. Misrati forces armed with Katyusha rockets and Zintani militia fighters were deployed to intervene in the fighting alongside armor belonging to the National Army (Libya Herald, January 21). The Misrata militia and and Tripoli militias were withdrawn on January 21 after 18 people died in clashes, with local authorities comparing the actions of the militias to those of the Italian colonial army (Libya Herald, January 22). The Warshefana are regularly accused of being pro-Qaddafi and held responsible for a wave of kidnappings and car-jackings around Tripoli.

The Killings in Kufra

A seemingly intractable conflict in Kufra Oasis between the Tubu and the Zuwaya Arabs (who seized the region from the Tubu in 1840) flared up again on January 20, as Arabs and Tubu shelled each other with mortars over the next few days. The struggle between the two tribes, both of whom would like to have full control of the smuggling/trade routes that run from the African interior through Kufra, has also been carried on by continuing tit-for-tat kidnappings of random members of rival communities.

However, Isa Abd al-Majid, leader of the Tubu fighters around Kufra, does not identify the Zuwaya as the real problem in the region: “We are fighting al-Qaeda. They want to eradicate us to occupy our land and control the frontiers with Chad and Niger, which will permit them to attack the French military base in Niger and kidnap Westerners” (Paris Match, January 20).

Government Response – Revival of the Militias

Libya’s ruling General National Council (GNC) declared a State of Emergency on January 18, citing the clashes in Sabha. Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan called on the revolutionary militias to rally to the south to expel the Qaddafists and restore order in the south and other security “hotspots” (Libya Herald, January 18). The government’s decision to recall the militias in the midst of efforts to demobilize them and integrate their members into the Libyan National Army has dismayed many Libyans who have become exasperated with the militias’ roadblocks and almost daily violence. Prime Minister Zeidan said the Misrata militia had been “commissioned by the government to conduct a national task… to spread security stability in the region” (al-Arabiya, January 18). Tubu Colonel Barka Warduko, the head of the Murzuk Military Council, claimed that Ali Zeidan was provoking and exploiting tribal clashes in the south to create a security crisis that would prevent the replacement of his government (Libya Herald, January 21).

The GNC released a statement insisting it had not abandoned laws 27 and 53 (ordering the demobilization of the militias), but their recall was an effective admission that the government security forces are unable to restore security on their own, providing the militias with a reason for their continued existence. Many Libyans felt the militias had lost the justification for their existence after the Misrata Brigade opened fire on anti-militia demonstrators in Tripoli on November 15, 2013, killing 47 people. Though the GNC claims it has not reversed its policy on militia demobilization, it is now clearly saying one thing and doing another.

Tubu demonstrators blockaded the Sarir power station (near Jalu Oasis in eastern Libya) for several weeks in December and January to demand greater representation in Kufra’s municipal government and an extension of the power supply to the Tubu community at Rebyana.

Other Tubu have been integrated into the National Army, most notably the mostly Tubu 25th Brigade, charged with guarding the Sarir, Messla and al-Shula oil facilities in eastern Libya. Three soldiers of the 25th Brigade on a supply run from Sarir to the nearby Jalu Oasis were ambushed and killed in mid-January. The unit’s commander, Saleh Muhammad, speculated that the gunmen might have been the same as those responsible for a late December attack on a Sarir farm project, in which five attackers were killed but the project manager kidnapped (Libya Herald, January 18). Workers at the Sarir power station stopped work the next day due to security concerns, causing power shortages in Tripoli and Benghazi (Libya Herald, January 20).

Conclusion

By January 22, reconciliation talks had helped ease the intensity of the fighting in Sabha, though Sabha military commander Muhammad al-Ayat al-Busaif suggested there was still a problem with “Qaddafi loyalists, some of whom remain in the surrounding area, including the Tamenhint airbase” (Libya Herald, January 22). The Qaddafists remain shadowy, unidentified characters that provide the Tripoli government with a reason to reactivate its reliance on a more tangible threat, Libya’s unruly and independent militias.

The emergence of the elusive Qaddafists could, as suggested by some, to be part of an effort to create an external security crisis (as opposed to Libya’s internal security crisis) to preserve the Zeidan administration at a time when it is under strong criticism. While there is serious opposition to Zeidan’s government, there is no consensus on a replacement – considering Libya’s current state and the inability of the government to enforce its writ almost anywhere, it is questionable whether anyone would really want the job. Faced with the possibility of a non-confidence vote, Zeidan remarked: “I would be happy if the vote went through” (Middle East Online, January 20).

The Tubu are in the midst of a cultural revival (similar to that of the North African Berbers) as the tribe asserts its non-Arab status and demands recognition in the forthcoming Libyan constitution. They are unlikely to return quietly to the days when Qaddafi called them foreigners and withdrew their Libyan identity cards.

Regardless of who is responsible for starting or perpetuating each round of Tubu-Arab violence, there is no doubt that such violence encourages the incipient Tubu separatist movement, closely tied to the Tubu cultural revival. Though there is no proof of such intentions, it remains possible that some acts of Tubu violence may be committed by independence-minded militants with the intent of provoking further clashes to politicize the rest of the community. However, the growth of a Tubu separatist/independence movement in Libya would create immediate concerns in Chad and Niger, which also host Tubu populations with considerable military experience and expertise in modern desert fighting.

Note

- For previous clashes in Sabha, see “Arab-Tubu Clashes in Southern Libya’s Sabha Oasis,” Terrorism Monitor, April 5, 2012 and “Libya’s Sabha Oasis: Former Qaddafist Stronghold Becoming Regional Center of Insecurity,” Terrorism Monitor, April 19, 2013.

This article first appeared in the January 25, 2014 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

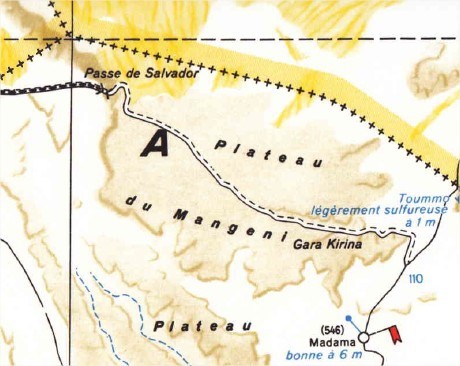

Passe de Salvador, top left; Fort Madama, bottom right.

Passe de Salvador, top left; Fort Madama, bottom right. French Legionnaires and Nigerien Troops at Fort Madama

French Legionnaires and Nigerien Troops at Fort Madama