Andrew McGregor

An Address to the Jamestown Foundation Annual Terrorism Conference, December 8, 2011, Washington D.C.

Gazwa al-Sanadiq – “The Conquest of the Ballot Boxes”

Gazwa al-Sanadiq – “The Conquest of the Ballot Boxes”

Egyptian militancy has reached a turning point following the national elections. Many former militant groups and other potential militant formations have been coopted by electoral success as they will now sit in the parliament they once threatened with violence. It is reasonable to ask if such groups are prepared for the long and difficult work of forming policy through consensus and writing legislation to see such policies through. Nothing in this process will match the instant gratification of producing a short list of demands and striking state targets in an effort to force compliance in the name of Shari’a and Islam. Nonetheless, religious movements that once damned democracy are now pursuing it as an unexpected pathway to power, urged on, in part, by youth factions that want immediate change even if it means dumping decades-old policies of abstaining from party politics.

So far, religious-based militancy in Egypt has proven to be a sure path to self-destruction or exile. The general public distaste for renewed religious and political violence on the scale seen in the 1990s precludes the adoption of violence by any groups seeking serious public support. The Islamist victory certainly reinforces the irrelevance of al-Zawahiri’s al-Qaeda movement, which through decades of indiscriminate slaughter has never been able to achieve the results gained by peaceful demonstrations and political organization. A leading Salafist ideologue, Dr. Najih Ibrahim, has said of al-Qaeda: “Their aim is jihad, and our aim is Islam.”

The Egyptian Revolution took all of Egypt’s Islamist factions by surprise, leaving even the well-organized Muslim Brotherhood caught off guard and without an immediate plan of how to best exploit the political unrest for its own benefit. In the end the movement’s conservative leadership found itself completely at odds with the movement’s youth wing, which took to protests in Tahrir Square and elsewhere against the wishes of the leadership.

While the radical Islamists of nearby Somalia still denounce “the degrading values of democracy,” Egypt’s Islamists have accepted democracy as a kind of revelation, one that revealed its potential in the March constitutional referendum, in which Islamists deployed enough voters to swing the decision their way.

Under the military regime, Egypt’s courts have approved the existence of numerous religious-based political parties, despite a ban on such groups in the existing constitution. Often with little more than a new name for their political wing, the Islamist movements have exploited this new tolerance of formerly banned groups to form a powerful political alliance. The question is how long can an alliance between the Salafist parties and the Muslim Brotherhood last. These two broad factions have numerous political and religious differences that account for a basic lack of trust. The electoral success of the Salafists seems to have actually widened the gulf with the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Muslim Brotherhood

Since a leadership turnover two years ago, the Muslim Brotherhood is now in the hands of a highly conservative leadership that would prefer to explore the possibilities of government even if this means meeting with American diplomats or working with the Egyptian military rather than antagonizing it. Their triumph at the polls was, after all, the triumph of the reforms that changed the movement from a Qutbist revolutionary movement to a grassroots, social welfare organization willing to assume political power in incremental stages. Though this approach has caused several rifts in the movement, it has still proved essentially correct, as witnessed by the election results. The catastrophic failure of the Qutb model has been replaced by the model of the Turkish Justice and Development Party. Nevertheless, the former leaders of the movement are watching to see whether the current leadership falters under the pressure they will face to initiate reforms in the Egyptian state.

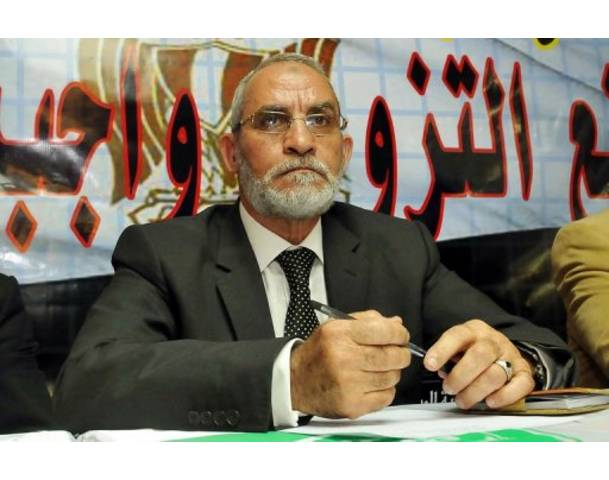

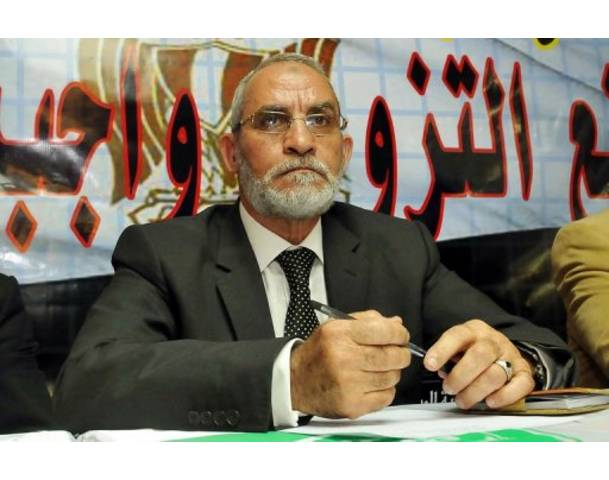

Dr. Muhammad Badie – Leader of the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt

Dr. Muhammad Badie – Leader of the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt

Though the Brotherhood has pledged not to run a presidential candidate, there will inevitably be pressure within the movement, given their electoral success, to skip a stage in the Brotherhood’s long-range plans and run a contender for the post. At the moment the Brothers are trying to persuade the military to approve a new government in which the chief power will lie in parliament rather than the presidency. Should this fail, it will increase pressure on the movement to enter the presidential contest. In the meantime, however, the Brotherhood’s cooperation with the military may backfire if Egyptians begin to view the movement as a collection of opportunists.

Brotherhood and Revolution

If the Muslim Brotherhood assumes a sober and even centrist stance as a responsible presence in government, this may allow the Salafists and fringe Islamic extremists to promote themselves through populist opposition to a conservative movement that, even if willing, will be unable to meet all the expectations of post-revolutionary Egypt.

The ever-pragmatic Brotherhood will not necessarily team up with the generally inflexible Salafists to dominate Egypt’s new parliament; a coalition with willing Liberal groups might be more likely, which could give the new government a more moderate and open tone. The Brothers have observed how the Islamist government of Turkey has managed to reconcile its own beliefs with continued cooperation with the West, to the point of maintaining its role as a vital NATO ally. At the best of times, Egypt is highly dependent on Western aid; with its currently shattered economy, there is little hope that an Islamist government could cut ties with America and the rest of the West unless Saudi Arabia and the Gulf nations were ready to step up and make up the financial shortfall that would follow. There are, however, no indications that this will happen in the immediate future.

The Salafists

Salafists have traditionally avoided participation in the political process. There is little doubt they will begin to disassociate themselves from the Muslim Brotherhood and let the Brothers’ inexperience at governance cause the Brotherhood’s followers to drift away to less-nuanced alternatives that promise quick solutions through a stricter observance of Islamic principles.

The Main Salafist Parties

- Nour (“Light”) Party

- Asala (“Fundamentals”) Party

- Islah (“Reform”) Party

- Al-Fadila (“Virtue”) Party

- Al-Bena’a wa’l-Tanmia (“Building and Development”) Party (Political wing of al-Gama’a al-Islamiya)

The Nour Party

The Nour Party has formed a coalition with three other Salafist parties; Asalah, Fadilah and Islah, enabling it to win nearly a quarter of the available seats and pose as a major rival to the Muslim Brotherhood. Army spokesmen have denied that General Sami Anan held talks this week with al-Nour Party officials regarding the creation of a new government. Imad Abd al-Ghafour, the chairman of the Nour Party, has suggested that his party may form a parliamentary coalition with the Muslim Brotherhood, but the Muslim Brotherhood is more likely to cooperate with liberals and secularists than their Islamist rivals in the Salafist parties.

One economic sector that may be threatened by the new realities in parliament is the vital tourist sector, an important source of hard currency and a lifeline for millions of Egyptians. The Salafists, however, do not look at tourism as an economic bounty, but rather a social and health threat caused by the spread of Western immorality and diseases such as AIDS. For the Salafists the great works of the ancient Egyptians are of no interest as they are works of the jahiliya, the age of ignorance that preceded the introduction of Islam. Potential bans on alcohol and mixed bathing would further devastate the tourism industry.

The Egyptian Military

The first priority of the military is preserving their privileges. The officer corps leads a comfortable life in luxurious officers’ clubs financed by their interests in a large segment of the Egyptian economy. For nearly any new government, a re-examination of military control of much of the nation’s industrial sector would be a top priority; however, it is entirely possible that the military has made a deal with the Muslim Brotherhood to overlook these privileges while the military does nothing to impede the Brothers’ political progress.

While the Army has attempted to be Turkish-style “Guardians of Democracy,” they still sent a strong message to the Egyptian people that their privileges are untouchable when they killed over 40 people in Tahrir Square last month who were protesting the military’s attempt to limit the constitutional authority of future governments over the military. The resignation of Egypt’s military-appointed cabinet that followed was not a promising start for the new Guardians of Democracy.

While the Army has attempted to be Turkish-style “Guardians of Democracy,” they still sent a strong message to the Egyptian people that their privileges are untouchable when they killed over 40 people in Tahrir Square last month who were protesting the military’s attempt to limit the constitutional authority of future governments over the military. The resignation of Egypt’s military-appointed cabinet that followed was not a promising start for the new Guardians of Democracy.

Though it continues to control the country, the Army is clearly displeased by the criticism it is now receiving. The discomfort of the ruling council has been seen in previously unheard-of activities by the army’s commander, Field Marshal Tantawi, who has gone so far as to take to the TV to explain that the army was not seeking power and even donning civilian clothes to mix with protesters in Tahrir Square. The Army has much at stake, including the annual $1.3 billion dollars it receives from the US for maintaining the peace with Israel. Tantawi and other military figures are also mindful not to end up in court facing charges like their late leader, Mubarak, and will take great measures to ensure their immunity from prosecution.

The military has been buffeted by hostile winds in recent weeks, but increasingly it has the upper hand as Egyptians demand a return to stability. A democratic transition is impossible without the military’s cooperation, and this will come at a price – immunity from prosecution, a continued military presence in the national economy and a constitutional clause removing the military from civilian oversight.

Egypt’s Coptic Christians

Shaykh ‘Abd al-Salam, Nour Party: “The best the Christians have ever been treated was under Islamic rule.”

Shaykh ‘Abd al-Salam, Nour Party: “The best the Christians have ever been treated was under Islamic rule.”

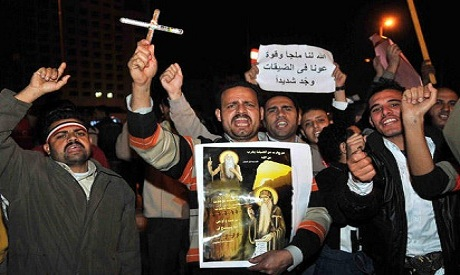

The Coptic revolutionary youth began ignoring the traditional non-confrontational directives from the Coptic religious leadership in the last few years. Coptic protests against the regime preceded those of Tahrir Square. While many Copts are alarmed at the escalating levels of sectarian violence, many of the youth have pledged to remain and fight for their rights as Egyptians, in the streets if necessary. The Coptic youth have already demonstrated they are no longer easy prey for Muslim mobs and have no interest in seeing the jizya tax on Christians revived. Some observers have noted that systematic discrimination against the Copts would result in two types of response: clashes in the streets and mass emigration.

International Repercussions

Egypt will also be tested internationally in the coming years. A conflict over water with Ethiopia and possibly Sudan is looming yet we know almost nothing about Salafist or Muslim Brotherhood views on issues like this. The West appears to be interested only in how an Islamist government would affect relations with Israel, but Egypt has other neighbors and faces foreign policy challenges that will leave the Islamists scrambling to form positions based on Islamic principles. This is not likely to be a pretty process for groups almost entirely focused on domestic issues and will possibly open the doors for serious divisions within the larger Islamist movement.

Israel

Problems with Israel include a controversial natural gas deal, Gaza, restrictions on Egypt’s military presence in the Sinai and the 1979 peace treaty.

The Muslim Brotherhood is looking for amendments to the 1979 peace deal rather than outright revocation. A similar position is held by most of the Salafist groups. Even if a more radical position was adopted, it would immediately run into some serious realities, including the sure loss of Egypt’s military subsidy from the United States, something not desired by the military. Although nearly all Egypt’s military exercises are focused on “an unnamed country to the northeast of Egypt,” the hard fact is that unlike the battle-hardened army that took the Suez Canal in 1973, the modern Egyptian army has not been involved in any serious fighting in the last four decades and the Air Force is no more likely to meet success against Israeli jets now than it was in 1967 or 1973.

Nonetheless, should Israel and/or the United States attack Iran, it is possible that some elements of the Islamist majority in parliament will flex their new-found muscle and access to the state’s armed forces to agitate for military retaliation of some sort.

The Sinai

The pipeline supplying natural gas to Israel and Jordan has been hit by gunmen eight times since the revolution began, leading Israel to begin seeking alternative sources of fuel. A policeman was killed just two weeks ago at a building used by al-Takfir wa’l-Hijra (Excommunication and Exodus), a relatively new militant group using a recycled name. Al-Takfir’s leader, Muhammad al-Teehi (Muhammad Eid Musleh Hamad) was arrested last month along with 16 other suspects, but the continuing grievances of the Sinai Bedouin and the cooperation of some members of their community with smugglers and Gazan militants suggest that the violence in the Sinai is far from over. Israel is constructing a massive 240km fence along its Sinai border with Egypt to counter Egyptian and Palestinian militants, Bedouin smugglers and African migrants trying to enter Israel.

Limits on an Egyptian military presence in the Sinai dictated by the 1979 peace agreement with Israel have hampered Egyptian efforts to cleanse the region of militants. However, some Israeli politicians have suggested that a greater Egyptian military deployment in the Sinai must be regarded as an act of war. Major General Uzi Dayan, the former head of the Israel National Security Council, has recently proposed a third way, urging the creation of an Israeli counterterrorism intervention force for deployment in the Sinai when necessary. Needless to say, this idea is unlikely to receive approval from any political movement in Egypt.

Conclusion

The massive social transformation taking place in Egypt is of the type that usually takes decades to sort out. The upsurge in Islamist political support may just be a phase in this transformation, leaving the possibility open that spurned Islamists might return to militancy. For now, however, the Islamist Parties must make a major change from small, highly disciplined cells designed for armed activities and the larger, less controllable composition of a political party pursuing a democratic process where numbers count. Egypt faces major economic, security and environmental challenges that will not be dealt with by a parliament obsessed with questions of appropriate dress for women and the evils of gender-mixing.

Islamists will focus on the constitution, the key to Egypt’s future direction. There is little question that the Islamist believe their electoral triumph will give them a strong position in the 100 man panel that will revise the constitution, but the Armed Forces have said they will select 80 of the 100 members. The constitutional fight is sure to turn ugly relatively quickly.

Meanwhile the Salafists will be inevitably transformed by their venture into politics, previously a long-taboo realm for the followers of the Pious Ancestors. Though they have eagerly and surprisingly taken to party politics, some residual distaste for mixing politics and religion was expressed when most of the Salafist parties agreed that preachers should not stand for office. The political transition will be hardest of all for the Salafists, who have the least political experience and are the most likely to be intolerant of views differing from their own rather inflexible beliefs. They will, in addition, be hard-pressed to restrain some of the more militant elements of the Salafist movement.

Meanwhile the Salafists will be inevitably transformed by their venture into politics, previously a long-taboo realm for the followers of the Pious Ancestors. Though they have eagerly and surprisingly taken to party politics, some residual distaste for mixing politics and religion was expressed when most of the Salafist parties agreed that preachers should not stand for office. The political transition will be hardest of all for the Salafists, who have the least political experience and are the most likely to be intolerant of views differing from their own rather inflexible beliefs. They will, in addition, be hard-pressed to restrain some of the more militant elements of the Salafist movement.

To be honest, there was very little reason to vote for many of the non-Islamist parties in the Egyptian election. They were poorly organized, had not had sufficient time to determine policy or platforms, and would likely have been hard-pressed to draw on sufficient talent to run a government if they did win. In the midst of the social, political and economic chaos that is currently engulfing their country, Egyptians turned to those who could say with confidence that they had the answers to these problems. Nine months after the rush of excitement that came with the overthrow of Mubarak, Egyptians are now tired of the seemingly endless round of strikes, disruptions and demonstrations. The Brothers’ motto is “Islam is the Solution.” The Egyptian public seems willing to give the Islamists a chance to prove it.

Popular Defense Forces Rally in Khartoum

Popular Defense Forces Rally in Khartoum