McGregor, Andrew: Darfur in the Age of Stone Architecture c. AD 1000 – 1750: Problems in Historical Reconstruction, BAR International Series 1006, Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 53, 2001

Please note the names from the King-lists have not been included in the index.

Footnotes are indexed for content but not citations.

A

Aba Kuri: 96(fn.44)

Abalessa: 14, 14(fn.29)

‘Abbasids: 24, 25, 26(fn.39), 28(fn.65), 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 43, 48, 50, 50(fn.64), 51, 52, 55, 56, 128

‘Abd al-Gadir: 38,

‘Abd al-Karim, Sultan: 44, 45, 56, 77-78, 88

‘Abd al-Karim ibn Yame: 28(fn.65), 43

‘Abd al-Majid, Sultan: 44

‘Abd al-Qadir: 68

‘Abd al-Rahman al-Rashid, Sultan: 96, 96(fn.39)

‘Abdallahi ibn Muhammad al-Khalifa: 62(fn.38)

‘Abdallab Arabs: 50(fn.64), 126

‘Abdullah Gema’a (Jama’a): 126-127

‘Abdullah Wad Hasoba al-Moghrabi: 62(fn.36)

‘Abdullahi Bahur, King: 28

‘Abdullahi Kamteinye, Sultan: 30

Abéché: 45, 77

Abo: 96(fn.44)

Abraham: 36(fn.44)

Abtar: 128(fn.68)

Abu Asal: 88, 95

Abu Delayk: 117

Abu Deleig: 125(fn.37)

Abu al-Fida: 22(fn.4), 23, 52

Abu Garan: 118-119

Abu Hadid: 129, 130

Abu Hamed: 37(fn.46), 124

Abu Hamid al-Gharnati: 38

Abu Haraz: 124(fn.32)

Abu Kundi: 89

Abu’l-Malik: 55

Abu Negila: 116(fn.4)

Abu’l-Qasim: 89, 89(fn.28), 96

Abu Qona’an: 16, 74, 117, 122(fn.6), 123, 128-130, 128(fn.68), 132, 140

Abu Sufyan (Sofyan): 122-124, 127, 127(fn.51), 130, 131, 134

Abu Suruj: 21

Abu Telfan: 23(fn.18), 45, 77

Abu Urug: 125

Abu Zabad: 28

Abu Zayd: 49-52, 52-53, 85

Abu’l-Sakaring Dynasty: 50

Abunjedah: 54

Al-Abwab: 37, 37(fn.46), 129, 129(fn.78)

Abydos: 25

Abyssinia, Abyssinians: 26(fn.38), 38, 111(fn.12), 129, 129(fn.79)

Acien, Kwanyireth Bol: 75

Adams, William Y.: 68, 123, 132(fn.5), 134

Al-Adayk: 49

Addison, F.: 122

Adelberger, J.: 64(fn.57)

Adimo (Dimo): 75

Adindan: 68(fn.97)

Ador, King: 37, 129

‘Agab, King: 85

Agadez: 137

Agadez Chronicle: 130

Agathermerus: 16

Agumbulum: 130

Ahaggar: 13(fn.26)

Ahl al-Awaid: 86

Ahmad Adam: 36

Ahmad al-‘Abbasid: 50

Ahmad Arbaf, Faki: 35

Ahmad Bakr, Sultan: 88-89, 93(fn.10), 95, 96, 96(fn.44)

Ahmad al-Daj: 25, 26, 27, 27(fn.45), 28, 29, 30

Ahmad al-Dia: 29

Ahmad Hamid: 61, 62(fn.37)

Ahmad al-Kabgawi: 27

Ahmad Kanjar: 45

Ahmad al-Ma’qur: 10, 18, 44, 46(fn.31), 49-56, 50(fn.60), 84-85, 87, 112(fn.26), 139

Ahmad al-Turkan: 28

Aidhab: 65

Ainyumba Daifani: 116

Aïr: 113, 130, 137

Akec La, Queen: 75

Akurwa: 75(fn.2)

Alans: 36(fn.44)

Albanians: 74

Albinism: 129, 129(fn.86)

Alexander the Great: 29, 36-39, 36(fns.44-45), 37(fns.51-52),

Alexandria: 126(fn.44)

Algeria: 13-14, 20,

‘Ali, A. Muhammad: 9

‘Ali Ahmad: 119(fn.36)

‘Ali Dinar (Sultan): 4, 11, 11(fn.s 10, 11), 12, 34(fn.26), 34(fn.29), 35, 43(fn.3), 45(fn.23), 54, 57(fn.5), 62(fn.38), 69, 78(fn.14), 96, 96(fn.38), 96(fn.40), 116, 116(fn.1)

‘Ali Dunama: 72

‘Ali Ghaji Zeinama: 72

‘Ali ibn Ahmad, Sultan: 72

‘Ali Korkorat, Sultan: 59, 59(fn.15)

‘Ali Musa: 45

Almásy, László Ede: 127(fn.57)

Almohads: 52

Almoravids: 110(fn.1)

Alwa (Aloa): 37(fn.46), 62(fn.36), 122, 123, 126(fn.44), 127, 131

Ama Soultane: 77

‘Amara Dunqas: 126

Ambus Masalit: 78(fn.14)

Amdang: 86

Aminu, Muhammadu: 16

Ammon: 37, 37(fns.53-54), 38

Ammon (place-name): 128

Amsa, Queen: 72

Amun-Re: 37

Anakim: 128

‘Anaj (Anag, Anak): 48(fn.53), 117, 122, 122(fn.6), 123-131, 123(fn.12), 124(fn.32), 125(fns.37,38), 127(fns.57,58), 128(fns.60,68), 130(fn.92), 140

Andal: 29

Andalus: 48

Anderson, AR: 37(fn.50)

Anedj: 129

‘Angarib, Sultan: 26, 27

Anglo-Egyptian Condominium: 12, 13, 27, 27(fn.52), 62(fn.42), 79, 124

Ani, King: 129, 129(fn.77)

Annok: 36(fn.41)

Anthony: 13(fn.26)

Arab, Arabs: 17, 18, 24(fn.25), 26, 28(fn.65), 31(fn.5), 36(fn.44), 43(fn.6), 44, 44(fn.8), 45, 45(fn.23), 48, 49, 50(fn.60), 53(fn.90), 55, 56, 57(fn.2), 62, 63(fn.47), 72(fn.128), 87, 88(fn.18), 89, 111, 111(fns.11,12), 116, 117, 119, 125(fn.33), 125(fn.37), 126, 128(fn.68), 129, 130, 139

Arabia: 2, 26(fn.38), 27, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 38, 50, 117, 135, 136

Arabic: 11(fn.11), 13, 44(fn.13), 63, 64(fn.54), 71(fn.119), 73(fn.142), 75(fn.7), 77(fn.9), 96(fn.41), 97, 104, 109, 110(fn.1), 111(fn.11), 117(fn.15), 140

Arari: 96(fn.41)

Arin Dulo: 31

Arkell, AJ: 1, 7-9, 12, 16, 20, 21, 23(fn.16), 25, 26, 27, 29(fn.69), 31, 31(fn.6), 33, 33(fn.18), 34, 34(fn.25), 34(fn.30), 36, 36(fn.39), 38, 38(fn.57), 44(fn.13), 45, 45(fn.21), 46, 46(fn.31, 32), 46(fn.35), 47, 48, 50, 53(fn.90), 54, 56, 57, 57(fn.1), 59(fn.9), 60, 60(fn.24), 61, 62, 62(fn.37), 63, 63(fn.49), 64, 64(fn.53), 65, 65(fn.67), 66-69, 68(fn.97), 69(fns.101,102), 70-71, 70(fn.111), 71(fn.118), 72, 72(fn.129), 74, 75, 75(fn.7), 78(fn.14), 91(fns.2,3,7), 93, 93(fn.8), 94, 94(fns.21,22,27), 95, 96(fns.39,41), 97, 97(fn.46), 112, 112(fn.21), 113, 115, 116, 116(fn.4), 117, 118, 122(fn.6), 123, 123(fn.13), 127, 128, 130(fn.96), 132, 134

Arianism: 137

Arlas: 128(fn.68)

Armenia, Armenians: 52(fn.79)

Armi Kowamin: 64(fn.53)

Ary: 129

Asben: 130

Ashdod: 128

Ashmolean: 65

Assyrian: 8, 28(fn.65)

Aswan: 110, 116, 137

Asyut: 5, 125

Atbara: 88, 116, 131

Aule: 63

Aurès: 20

Aurungide Dynasty: 116

Awlad Mahmud: 130

Awlad Rashid: 72(fn.128)

Awlad Sulayman: 44, 63(fn.47)

Axum: 113

Ayesha: 55

‘Ayn Farah: 33, 36(fn.39), 54(fn.99), 56, 57(fn.5), 61, 64-74, 64(fn.60), 65(fn.67), 66(fn.75), 67(fn.86), 69(fn.100), 69(fn.102), 91(fn.3), 112, 122, 127, 131, 132, 134, 137, 139

‘Ayn Galakka: 55, 66(fn,75), 73-74, 73(fns.146,148), 128(fn.68)

‘Ayn Siro: 60(fn.23)

‘Ayn Sirra: 72(fn.129)

Ayyubid: 23

Axum, Axumites: 8

Azagarfa: 96(fn.41)

Al-Aziz, Caliph: 52(fn.79)

B

Babaliya: 48,

Babylon: 22

Bachwezi: 18

Bacquié, Captain: 134

Badanga Fur: 71

Badar: 136

Badi, Sultan: 87

Badr al-Gamali al-Guyushi: 52(fn.79)

Bagari: 116

Baghdad: 50, 52

Bagirmi: 5, 7, 27(fn.55), 43, 62, 63, 75(fn.3), 88, 95, 111, 111(fn.11), 119, 135

Bagnold, RA: 116

Bahar: 91

Baheir Tageru: 125

Bahnasa: 43(fn.6)

Bahr, Wazir: 89

Bahr al-Arab: 27(fn.55), 75

Bahr al-Ghazal (Chad): 67(fn.86), 73, 74, 132-135, 132(fn.1)

Bahr al-Ghazal (South Sudan): 23, 25, 27(fn.45), 27(fn.55), 29, 31(fn.5), 33(fn.12), 75, 128(fn.68), 132(fn.1)

Bahr al-Jamal: 56

Baiyuda Wells: 124

Balal: 111(fn.11)

Balfour Paul, HG: 1, 8(fn.19), 17, 20, 26-27, 28, 31, 35, 36(fn.41), 38(fn.60), 44, 60, 60(fn.24), 61, 61(fn.29), 62, 65, 66, 66(fns.75,77), 68(fn.92), 69, 70, 72, 95

Banda: 7, 27(fn.55)

Bani Abbas: 48

Bani Habibi: 16

Bani Mukhtar: 16

Bantu: 27(fn.55)

Banu Hillal: 44, 46(fn.31), 48, 48(fn.53), 49, 51, 51(fn.71), 52, 52(fns.79, 80), 52(fn.86), 53, 57(fn.2), 85, 117, 120(fn.46), 129

Banu Sulaym: 52, 52(fn.79)

Banu Ummaya: 64(fn.53)

Bao: 49

Baqqara: 24, 27(fn.55), 44, 50(fn.60)

Barah (Bazah): 129

Barakandi: 31(fn.6)

Barani Berbers: 128(fn.68)

Barboteu, Lieutenant: 48

Barca: 64

Bargala: 57(fn.1)

Bariat: 55

Barkindo, BM: 46, 46(fn.30), 47, 111(fn.12), 136, 136(fn.32), 137, 137(fn.41)

Barqat Umm Balbat: 124

Barquq, Sultan: 111(fn.12)

Barr: 128(fn.68)

Barr ibn Qays ‘Aylan: 38

Barra, Battle of: 54

Barrjo: 31(fn.4), 128(fn.68)

Barth, Heinrich: 5, 43, 43(fn.6), 46, 46(fn.27), 57(fn.2), 111

Basa: 129(fn.78)

Basi: 28(fn.60)

Basigna: 119(fn.37)

Batálesa: 43, 43(fn.6)

Batnan, King: 85

Bayko: 23, 23(fns.17, 19), 25, 25(fn.29), 27(fn.45), 29, 88

Bayko King-List: 42

Bayt al-Mayram: 61, 69, 69(fn.102)

Bazina à degrès: 20, 20(fn. 22), 118(fn.27)

Beaton, AC: 16, 87, 87(fn.9)

Bedariya: 128

Bedde: 63

Befal: 129

Beja: 22, 132

Beliin: 137

Bell, Herman: 130(fn.92)

Bender, Lionel M.: 6, 23, 119(fn.34), 128(fn.60)

Bénesé: 43, 43(fn.6)

Benghazi: 77(fn.1)

Beni – see Bani

Benoit Pierre: 13, 13(fn.26)

Berber, Berbers: 7, 13, 14, 14(fn.29), 16, 17, 17(fn.15), 20, 21, 25, 26, 33, 36(fn.44), 38, 45(fn.25), 46, 46(fn.27, 30, 31), 48, 48(fn.53), 49, 52, 53, 53(fn.90), 57(fn.2), 61(fn.31), 62, 64(fn.53), 70, 72(fn.129), 77, 80(fn.2), 111(fns.11,12), 119, 122, 122(fn.6), 123, 125, 125(fn.33), 128, 128(fn.68), 129, 130, 130(fn.93), 137, 139

Beri: 23

Beringia, Battle of: 45(fn.23), 62(fn.42)

Berre, Henri: 24, 25

Berti: 33, 64, 116, 118-119, 119(fn.34), 120(fn.44)

Bayuda Desert: 125

Bible: 37(fn.52), 128

Bidayat: 27, 48, 48(fns.53, 54), 49, 49(fn.55), 72(fn.128), 117, 128(fn.68), 137

Bidayriya Arabs: 88(fn.18)

Bilaq: 33, 33(fn.22)

Bilia Bidayat: 137

Bilia Bidayat, Sections: 48

Bilma: 46

Biltine: 45

Binga: 7, 27(fn.55)

Bir Bai Depression: 77

Bir Natrun: 22(fn.1)

Birged (Birked): 51, 51(fn.71), 64, 64(fn.54), 88, 120, 120(fn.46)

Birged Sections: 120(fn.46)

Biriara Bidayat, Sections: 49

Birni: 56, 72(fn.134)

Bivar, AH: 11, 67(fn.86), 73(fn.144), 74

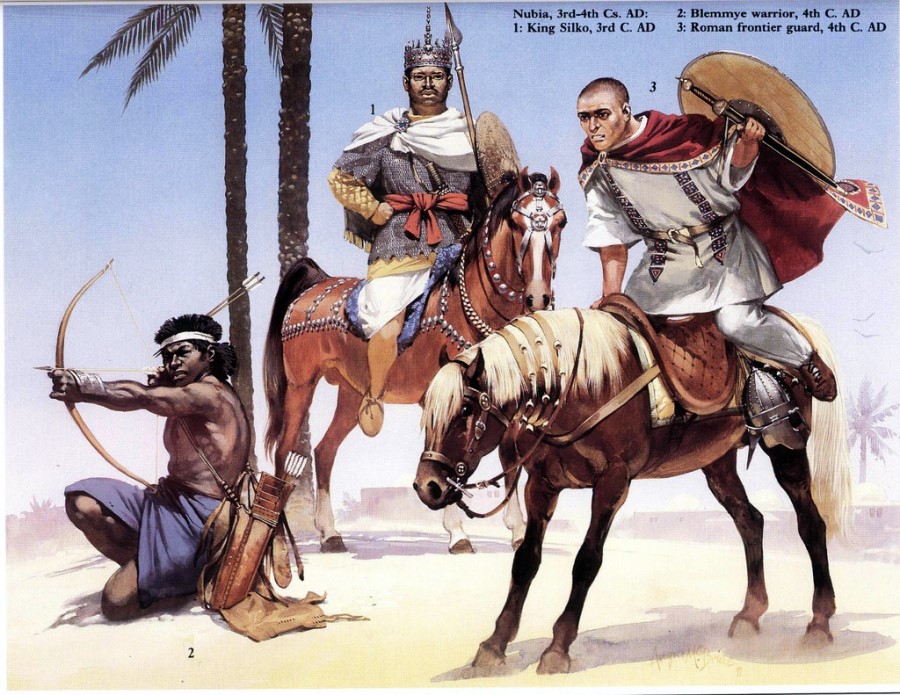

Blemmyes: 127(fn.58)

Blue Nile, Blue Nile Province: 7, 62(fn.36), 117

Bochianga: 132, 132(fn.7)

Bora Dulu: 9

Bordeaux, General: 73(fn.146)

Borgu: 135, 136

Borku: 44, 66(fn.75), 73, 74, 77(fn.1), 128, 132(fn.4), 137

Borno (Bornu): 5, 7, 11, 16, 16(fns. 4,7), 26(fn.39), 28, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 36(fn.44), 44, 46, 46(fn.27), 47, 47(fn.43), 48, 50, 50(fn.64), 51, 54, 57(fn.2), 63, 69(fn.101), 70, 70(fns.111,116), 71, 72-73, 72(fns.129,135), 74, 75, 75(fn.3), 77(fn.1), 80(fn.1), 88, 91, 110, 111, 111(fns.11.12), 112, 118, 119, 123, 127, 131, 137, 139

Bosnians: 74

Botolo Muhammad: 119(fn.36)

Brahim (Sultan): 44

Brands: 25, 46(fn.37), 70, 70(fn.107), 72(fn.129)

Braziers: 134

Brett, Michael: 52

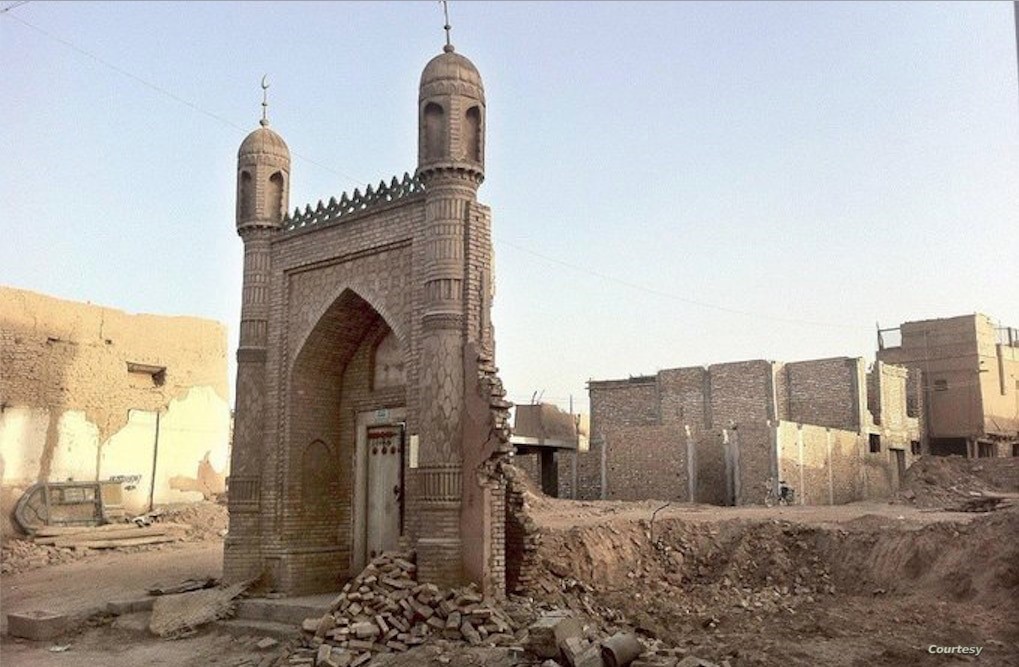

Bricks, Brick Construction: 65(fn.67), 66, 66(fn.75), 67(fn.86), 70(fn.109), 72-73, 73(fns.142,143,144,148), 74, 95, 96, 114, 122, 124, 126, 127, 132

Britain, British: 11(fn.10), 13, 45(fn.23), 62(fn.42), 65(fn.67)

British Columbia: 15

Brown, Robert: 111

Browne, WG: 5, 46(fn.37), 114, 130

Bruce, James: 38(fn.58), 89(fn.28)

Brun-Rollet: 52

Buba: 15

Budge, EA Wallis: 127(fn.58)

Bugiha: 137(fn.37)

Bugur, King: 29, 31

Bukar Aji: 136(fn.32)

Bulala: 44, 48, 56, 67(fn.86), 70, 73, 73(fn.143), 110, 111, 111(fn.11), 112, 112(fn.21), 137

Bulgi: 57(fn.1)

Burgu Keli: 57(fn.1)

Burnus: 128(fn.68)

Burundi: 115

Busa: 135

Bussa: 136

Butana: 130

Butr Berbers: 128(fn.68)

Byzacena: 137

Byzantium, Byzantines: 43(fn.6), 135, 135(fn.21), 137

C

C-Group: 45(fn.21), 132(fn.7), 134

Cailliaud, Frèdèric: 38, 46(fn.37)

Cain: 128

Cairo: 11(fn.9), 52, 52(fn.79), 63, 64, 78(fn.15), 111, 111(fn.12)

Cameroon: 5, 115, 136(fn.32)

Campbell, E.: 60

Canaanites: 128, 128(fn.68), 132

Canary Islands: 37, 130, 37, 130(fn.93)

Cannibalism: 78(fn.14)

Capot-Rey, MR: 132(fn.5)

Carbou, H: 27(fn.54), 44(fn.8), 46(fn.32), 53, 80(fn.1), 111-112

Carrique, Captain: 73-74, 128(fn.68)

Carthage, Carthaginians: 14, 115, 137

Caucasus: 35, 36(fn.44)

Celts: 36(fn.44)

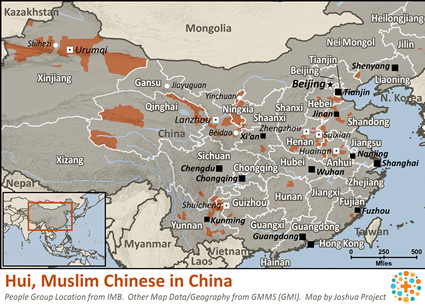

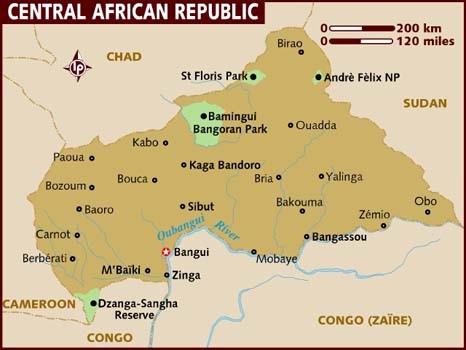

Central African Republic: 27(fn.55)

Chad: 7, 17, 22, 23, 27(fns.54,55), 31(fn.5), 44, 44(fn.13), 45, 48(fn.51), 66(fn.75), 67(fn.86), 72, 111(fn.9), 112, 113, 114, 132-137, 132(fn.7), 140

Changalif: 45

Chapelle, Jean: 44, 48

Chittick, HN: 125-127

Chokhorgyal Monastery: 35

Chosroe II (Chosroes, Khosraw, Kisra): 26(fn.38), 135, 135(fn.25)

Chouchet Tomb: 14, 14(fn.27), 20, 20(fn.21), 77, 118, 118(fn.27), 119, 119(fns.40,41,42)

Christianity, Christians: 8, 11, 23, 33, 36(fn.44), 38, 44(fn.13), 46, 46(fn.31), 46(fn.35), 46(fn.37), 47, 46(fn.37), 62(fn.36), 64(fn.54), 65(fn.67), 66, 67, 67(fn.86), 68-69, 69(fn.102), 70, 72(fn.129), 74, 110, 111, 112, 116, 117, 120, 120(fn.48), 122-123, 124(fn.29), 125-127, 126(fn.44), 130, 131, 132-137, 132(fns.4,6), 137(fn.41), 139-140

Chronicle of John: 137

Circassians: 74

Clapperton, H: 110(fn.3)

Clarke, Somers: 68

Cleopatra: 13(fn.26)

Cline, Walter: 48(fn.47)

Cohanim: 15

Cohen, Ronald: 11

Congo: 27(fn.55), 33(fn.12)

Copts (Egyptian): 111, 112, 123, 126(fn.44), 132, 135

Crawford, WF: 27, 38(fn.58), 123, 123(fn.13)

Crete: 38(fn.58)

Cromlech: 31(fn.10)

Crowfoot, JW: 130

Cunnison, I: 24

Cuoq, Joseph M.: 77(fn.9)

Currie, James: 46(fn.37)

Cyrenaïca: 37, 64, 77, 117

Cyrus the Great: 37(fn.52)

D

Dagio: 63

Dahia: 29

Daima: 114

Daju: 5, 6, 6(fn.6), 8, 12, 16, 18, 22-42, 22(fn.44), 23(fns.15, 16, 18, 19), 24(fn.21), 27(fn.45), 27(fn.52), 27(fn.54), 28(fn.58), 29, 29(fn.66-67, 71-72), 30, 30(fn.75,77), 31-42, 31(fn.6), 33, 33(fn.18), 34, 34(fn.25), 34(fn.29), 35, 36, 36(fn.45), 43, 44, 45, 51, 53(fn.98), 64, 64(fns.54,60), 72(fn.128), 75(fn.3), 87(fn.9), 91, 110, 112, 118, 118(fn.19), 128, 131, 139-140

Daju Hills: 27, 34, 113(fn.1)

Daju King-Lists: 40-42

Daju Sections: 24

Dak, son of Nyikango: 75

Dakin al-Funjawi: 88(fn.18)

Dakka: 116

Dala Afno (Dali Afnu, Afuno): 44, 70, 75, 91

Dala Gumami, Mai: 72

Dalatawa: 44

Dali: 31, 51, 54, 62-63, 71, 71(fn.118), 75, 75(fn.7), 76, 84, 87, 91, 93, 93(fn.10), 97(fn.45), 112(fn.26), 139

Dalloni, M: 119(fn.42), 130

Damergu: 47, 47(fn.46)

Danagla: 117

D’Anania, Giovanni Lorenzo: 63-64, 71

Danat, King: 29

Daoud al-Mireim, Sultan: 45

Dar Abo Dima: 51, 128

Dar Abo Uma: 51

Dar Birked: 89

Dar Dali (Daali): 62(fn.42), 75(fn.7)

Dar Dima: 75(fn.7)

Dar Erenga: 36(fn.41)

Dar Fertit (Fartit): 29, 112(fn.24)

Dar Fia: 87, 95

Dar Fur (see Darfur)

Dar Furnung: 43, 54, 64, 64(fn.60), 70, 72, 72(fn.129), 75, 86, 139

Dar al-Gharb: 75(fn.7)

Dar Hamid: 119

Dar Hawawir: 125

Dar Humr: 50, 50(fn.61)

Dar Kerne: 95

Dar Kobbé: 27(fn.45), 28(fn.65), 34(fn.25)

Dar Masalit: 30, 36(fn.41), 78(fn.14), 86

Dar Qimr (Gimr): 34(fn.25), 36(fn.41), 44, 45, 95

Dar al-Riah: 75(fn.7)

Dar Runga: 62(fn.42)

Dar Sila: 6(fn.6), 12, 23, 23(fn.18), 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 29(fn.72), 30, 34(fn.25), 36(fn.41), 45, 56

Dar Simiat: 33

Dar Sinyar: 44

Dar Tama: 27, 27(fn.45), 29(fn.72), 45, 79

Dar Tokonyawi: 75(fn.7)

Dar Tuar: 50, 34(fn.25), 50

Dar Uma: 75(fn.7)

Dar Wona: 29, 31, 93, 93(fn.10)

Dar Zaghawa: 33(fn.18), 50, 64(fn.53), 112, 112(fn.24)

Dar Ziyad: 44

Daranga Fur: 78(fn.14)

Darb al-Arba’in: 4, 5, 50, 60, 110, 112, 112(fn.25), 122(fn.6)

Dardai: 47, 47(fn.46), 48, 48(fn.51)

Darfur, Administrative Divisions: 75(fn.7)

Darfur, Geography of: 2-4

Darfur, Trade Routes: 4, 73, 77(fn.1)

Darsala: 47, 47(fn.46)

Date Palm Cultivation: 36, 48, 80(fn.2),

Daud Kubara ibn Sulayman: 129

Da’ud al-Mirayn: 77

Dawa: 57

Dawurd al-Miriri al-Modaddan, Sultan: 55

Daza Tubu: 16, 16(5), 34(fn.29), 45, 47, 137

Dazaga (Dazagada): 44(fn.13), 45

De Breuvery, J: 30, 50

De Cadalvène, E: 30, 50

De Lauture, PHS D’Escrayac: 87

De Medeiros, F.: 17

De Neufville, RL: 65, 65(fn.61), 66(fns.74,75), 67(fn.87), 68, 69(fn.100)

Debba: 31, 31(fn.4)

Debeira East: 67

Debeira West: 65, 65(fn.67)

Delil Bahar: 51, 63

Demagherim: 46(fn.27), 54

Dengkur: 34(fn.26)

Denham, D.: 72, 110(fn.3)

Derdekishia: 47-48

Dereiba Lakes: 34-36

Derihurti: 47

Dhu’l-Adh’ar: 39

Dhu al-Manar: 38

Dhu Nowas: 136

Dhu al-Qarnayn (see Alexander the Great)

Diab, Sultan: 45

Diffinarti: 68

Diffusionism: 8

Dilling: 75

Al-Dimashqi: 123

Al-Dinawari: 37

Dingwall, RG: 63, 65

Dinka: 128

Dionysus: 37(fn.50), 38

Dirku: 16

Dirma: 57

Divine Kingship: 35, 113, 139

Diyab: 49

Djelil al-Hilali: 84(fn.3), 85

Djourab: 132

Dolmens: 118(fn.27)

Donatism: 137

Dongola: 23, 43, 52(fn.86), 67(fn.86), 85, 117, 122(fn.6), 123, 129, 134

Dowda: 57, 57(fns.1-2), 60

Drums (see Nahas)

Dukkume, Malik: 87

Dulo Kuri: 57, 91-93

Dumont, Henri J.: 60(fn.18), 118-120

Dumua: 64(fn.60)

Durma: 57(fn.5)

Duros: 47

E

Edmonds, JM: 123, 125

Edwards, WN: 116(fn.1)

Egypt, Egyptians: 5, 7, 8, 11, 25, 33(fn.22), 38, 43, 52, 52(fn.79), 53, 54, 60, 63, 63(fn.47), 64, 71, 74, 88, 97, 110, 111(fn.12), 112, 112(fn.25), 113, 122(fn.6), 123, 123(fn.16), 125, 127, 128, 128(fn.67), 129, 131, 132, 134, 135

Eilai: 125

England, English: 54

Ennedi: 8, 27, 36(fn.39), 44, 44(fn.15), 46, 48(fn.54), 55, 77, 128, 128(fn.68), 137

Eparch: 38(fn.59)

Equatoria: 33(fn.12)

Erenga: 36(fn.41), 79

Errè: 45

Et-Terge Masalit: 78(fn.14)

Ethiopia: 37, 128(fn.68)

Eunuchs: 20, 57(fn.2), 62, 62(fn.42), 76

Evans-Pritchard, EE: 7, 75(fn.2)

F

Fara: 54

Faragab: 129

Farafra Oasis: 52(fn.80)

Faras: 38, 67, 69

Fashir: 75(fn.3), 89

Al-Fashir: 5, 9, 11, 11(fn.9), 34(fn.26), 45, 45(fn.23), 50, 62(fn.38), 63(fn.47), 69, 75(fn.3), 78(fn.14), 120(fn.46), 135

Fatimids: 52, 52(fn.79)

Fazughli: 27, 38, 128

Fazzan (Fezzan): 5, 20(fn.22), 45(fn.23), 48, 48(fn.51), 119(fn.41)

Felkin, RW: 34, 86, 87(fn.9), 114

Fella (Fellanga): 64(fn.60), 70

Fenikang: 75(fn.2)

Fentress, Elizabeth: 52

Ferti: 20

Fertit: 27, 27(fn.55), 30

Fez: 62(fn.36)

Fezzan (Fazzan): 63(fn.47), 73, 74, 119

Fiki Khalil: 54

Fiki Muhammad Tahir: 62(fn.38)

Fileil, Sultan: 30

Filga: 59, 94, 95

Fir: 27(fn.55)

Fira: 64(fn.53)

Firat: 27(fn.55)

Fisher, AGB: 111(fn.11), 112, 112(fn.26)

Fora: 51

Forang Aba: 71

Foranga Fur: 71

Forei: 95

Foucauld, Pére: 13

France, French: 13, 30, 30(fn.78), 34(fn.29), 48(fn.51), 63(fn.47), 65(fn.67), 73(fn.146)

Franciscans: 137

Frobenius, Leo: 135

Fuchs, P.: 72(fn.128)

Fugbu (Fugobo): 80(fn.3)

Fulani: 36(fn.44), 72, 119

Funj: 24(fns.21, 25), 25, 31(fn.4), 38, 38(fn.57), 51, 87, 88(fn.18), 89, 95, 112, 126, 128(fn.60), 129, 131

Funj Chronicle: 51, 126, 126(fn.44), 127, 131

Fur: 6-7, 11, 16, 17, 18, 27(fn.55), 28, 29(fn.71), 30, 31, 33, 34, 34(fn.25), 36, 45, 45(fn.18), 51, 53, 55, 57, 57(fn.2), 62, 64, 64(fns.53,54), 71, 71(fns.120,123), 75, 78(fn.14), 79, 86-109, 86(fn.7), 91(fn.5), 123, 139

Fur King-Lists: 97-109

Fur Language: 86, 86(fn.2), 94(fn.22)

Furnung Hills: 60, 60(fn.23), 119(fn.38)

Furogé (Feroge): 27, 27(fn.55), 29(fn.73), 30

G

Ga’afir Gurmun (Germun), King: 85

Gabir: 64

Gabri: 20

Gaéda: 44, 44(fn.15)

Gamburu: 69(fn.101), 72-73

Gami Kheir, Malik: 116(fn.1), 118

Gao: 110(fn.1)

Gaoga: 33, 110-112, 110(fn.1), 112(fns.21,24,26)

Garamentes: 115, 130

Garoumélé: 73, 73(fn.143)

Garu: 72(fn.135)

Gedaref: 50

Garstang, John: 62

Gath: 128

Gaya: 136(fn.32)

Gaza: 128

Gelti al-Naga: 130(fn.94)

Genealogy: 5, 11(fn.11), 12-15, 24, 47(fn.46), 53(fn.91), 84, 96(fn.41), 97, 111(fn.12), 128(fn.68)

Geneina: 86

Genies (Jinn): 62(fn.38)

German: 64(fn.57)

Gezira: 129(fn.78)

Ghabashat, Battle of: 89

Ghana: 22, 135

Gharbanin: 25(fn.29)

Ghazali: 67, 134

Ghudiyat Arabs: 87

Ghulam Allah ibn ‘Ayd: 28(fn.65)

Ghumsa: 46

Ghuzz: 74

Giants: 31(fn.4), 53-54, 73, 74, 123, 128, 128(fn.68)

Giggeri, Sultan: 88, 95

Gilgamesh: 37, 37(fn.50)

Gili: 78

Gillan, Angus: 7, 35, 35(fn.34)

Gillif Hills: 125

Gillo: 75

Ginsi: 87

Gitar, King: 28

Gitxsan: 15

Glass: 65-66, 65(fn.67)

Gnol: 23(fn.15)

Gobir: 135

Gog and Magog: 36, 36(fn.44)

Gogorma: 95

Gold: 71

Gordon-Alexander, LD: 96(fn.40)

Goths: 36(fn.44)

Greece, Greek: 7, 28(fn.65), 37, 38, 65(fn.67), 126(fn.44), 132, 135(fn.25), 137

Gros, René: 29, 44(fn.17)

Guanche: 130(fn.93)

Gula: 27(fn.55)

Gule: 128(fn.60)

Gunda: 47(fn.46)

Gura’an (Kura’an): 25, 34(fn.29), 56, 132, 137, 137(fn.37)

Gurli (Gerli): 95

Gurri: 95

Gurzil: 37(fn.53)

H

Haaland, R.: 114

Hababa, Habuba’at: 62(fn.38), 97

Habasha: 22, 23, 33(fn.22)

Hache à gorge axe: 125

Haddad: 113

Hafir: 120, 125, 125(fn.37), 130

Hajang Keingwo: 97, 97(fn.46)

Hajar Kudjuna: 25

Hajar Kujunung: 30,

Hajar Te’us: 28(fn.65)

Hajj ‘Ali: 50

Hajj Brahim Delil: 63

Ham, Hamites: 6-7, 8, 22, 25, 26, 38, 46, 125(fn.33), 128

Hamad ‘Abbas Himyar: 29(fn.73)

Hamaj (Hamej): 128, 128(fn.60)

Hamid bin Abdullah: 96(fn.41)

Hamid Ahmad: 28(fn.64)

Hammad bin Tamr: 119

Harim: 57(fn.2), 62(fn.42)

Harkhuf: 45(fn.21), 116

Harkilla: 135

Harut: 78

Hassaballah, General: 126

Al-Hassar, Sultan: 44

Hausa: 44, 70, 73(fn.143)

Hauya Hoe: 59, 113, 119

Hawara Berbers: 125, 125(fn.33)

Hawawir: 125, 125(fn.33),

Haycock, BG: 113

Haydaran, Battle of: 52

Haykal: 68

Hebrew, Hebrews: 36(fn.44), 128

Hebron: 65, 128

Helbou: 27(fn.31)

Helmolt, Dr.: 77(fn.9)

Henderson, KDD: 29

Henige, DP: 14, 84

Heracles: 37(fn.50)

Heraclius: 135

Herodotus: 11

Al-Hidjr: 28(fn.65)

Hijaz: 27(fn.53), 27(fn.54), 28(fn.65), 49, 78, 136

Hill, LG: 25

Hill Nubian: 120

Himyarites: 18, 26, 26(fns.38, 39), 29(fn.73), 38, 39, 38(fn.61), 49, 111(fn.12), 125(fn.33), 135, 136

Hobbs, Capt. HFC: 35, 35(fn.34)

Hobson, RL: 70

Hoes (see also Hauya hoes): 122, 122(fn.6)

Hoggar Mountains: 13, 20(fn.22),

Holt, PM: 48(fn.53), 51, 51(fn.74), 98

Holy Stones (see Stone Worship)

Houghton, AA: 65, 65(fn.61), 66(fns.74,75), 67(fn.87), 68, 69(fn.100)

Howara: 119

Hrbek, I: 63(fn.47), 71(fn.1244), 112

Huard, P.: 113, 132(fn.7), 134

Huddleston, Major HJ: 35

Hudud al-Alam: 132-134

Human Sacrifice: 78

Hummay, Sultan: 111(fn.12)

Hungarians: 74

Huns: 36(fn.44)

Hurreiz, Sayyid Hamed: 54

Husayn (Hussein) Abu Koda: 78(fn.14)

Husayn Morfaien, Sultan: 30

I

Ibadites: 137

Ibn ‘Abd al-Zahr: 129

Ibn Abi Zar of Fez: 125(fn.33)

Ibn al-‘Arabi: 23

Ibn Assafarani: 130,

Ibn Batuta: 64(fn.53)

Ibn Hazm: 38

Ibn Kathir: 37

Ibn Khaldun: 23, 38, 52, 52(fn.78)

Ibn Qutayba: 6

Ibn Sa’id: 22, 23, 37, 136

Ibn Selim al-Aswani: 37(fn.46), 62(fn.36), 126(fn.44), 127, 129(fn.78)

Ibn Shaddad: 52

Ibn al-Wardi: 33(fn.22)

Ibrahim (Pretender to the Fur Throne): 78(fn.14)

Ibrahim, Sultan (Fur): 5, 62(fn.38), 96, 116

Ibrahim, Sultan (Tunjur):

Ibrahim al-Dalil (see Dali)

Ibrahim Musa Muhammad: 7, 9, 9(fn.9), 68(fn.88), 70(fn.111)

Ibrahim bin ‘Uthman, Sultan: 110

Idris Aloma, Mai: 70, 70(fn.111), 71, 72-73, 75(fn.3), 123

Idris Ja’l: 87

Idris Katargarmabe (Katarkanabi), Sultan: 112

Al-Idrisi, Muhammad: 17, 22, 33, 45(fn.25), 111, 112(fn.20), 137

Ifriqsun bin Tubba Dhu al-Manar: 38

Ihaggaren Tuareg: 13

Illo: 136

Imam Ahmad: 47

Imatong Hills: 33(fn.12)

India, Indian: 63, 63(fn.47)

Iriba Plateau: 77,

Irima: 64(fn.53)

Iron, Iron-working: 33, 59(fn.13), 62, 70, 93, 113-115, 114(fns.12,16), 119-120, 120(fn.43), 122, 123, 123(fn.16), 140

Irtet: 116

Irtt: 116,

Isabatan: 13

‘Isawi bin Janqal: 89

Islam, Islamization: 11, 12, 18, 28(fn.65), 34, 36(fn.44), 44, 48, 50, 53(fn.90), 55, 62(fn.38), 69, 70-71, 71(fn.124), 72(fn.128), 73, 86-87, 86(fn.7), 89, 95, 97, 110, 111(fn.12), 112, 117, 117(fn.14), 118, 127, 135-136, 139

Isma’il Ayyub Pasha: 75(fn.7), 103-104

Israel: 128

Italy, Italians: 34(fn.29), 54, 63(fn.47),65(fn.67), 110(fn.1)

Iya Basi: 78(fn.14)

J

Ja’aliin Arabs: 25, 26(fn.39), 28(fn.65), 45, 119

Jackson, HC: 124, 124(fn.32), 125(fn.37)

Jacobites: 137

Jallaba Hawawir: 125(fn.33)

Jalut: 13(fn.25

Janakhira: 27(fn.55)

Janqal (Jongol), Sultan: 88, 88(fn.18)

Japheth: 36(fn.44)

Jarma: 56

Jawami’a: 96-97, 96(fn.41), 129

Jayli: 51

Jebel ‘Abd al-Hadi – see Jebel Haraza

Jebel Adadi: 95, 95(fn.31)

Jebel Afara: 96(fn.38)

Jebel Aress: 48

Jebel Au: 18

Jebel al-Azib: 129

Jebel Bayt al-Nahas: 129

Jebel Belbeldi: 130(fn.94)

Jebel Burgu: 28(fn.65)

Jebel Doba: 31

Jebel Eisa: 60, 118

Jebel Ferti: 59

Jebel Foga: 21, 91, 91(fn.3), 93, 95

Jebel Forei: 93

Jebel Gelli: 50(fn.63)

Jebel Gidera: 36(fn.41)

Jebel Gurgi: 54

Jebel Haraza: 33, 123, 123(fn.12), 129, 129, 129(fn.77), 130-131, 130(fns.87,94), 131

Jebel Hileila: 33,

Jebel al-Hosh: 125

Jebel Hurayz (Harayz, Hereiz): 43, 48-9

Jebel Irau: 126

Jebel Jung: 64(fn.53)

Jebel Kaboija: 117

Jebel Kadama: 45

Jebel Kadjanan: 30

Jebel Kadjano: 25

Jebel Kajanan: 30

Jebel Karshul: 130

Jebel Katul: 129

Jebel Keima: 16, 31(fn.6), 93

Jebel Kerbi: 60

Jebel Kilwa: 28, 30, 31, 33

Jebel Kurkeila: 130

Jebel Kwon: 135

Jebel Liguri: 23

Jebel Mailo: 53

Jebel Maman: 127(fn.58)

Jebel Marra: 1, 7, 9, 16, 17, 20, 21, 25, 27(fn.55), 28, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.66), 31, 33, 34, 36, 36(fn.41), 38, 45, 51, 53, 54, 57(fn.5), 62(fn.42), 66, 78(fn.14), 86, 87-90, 91, 93-95, 94(fn.21), 112, 119(fn.38), 128, 131, 139

Jebel Masa: 59, 72(fn.129)

Jebel Meidob – See Meidob Hills

Jebel Mogran: 117

Jebel Mojalla: 95

Jebel Moya: 130

Jebel Mun: 79

Jebel Mutarrak (Mutarrig): 59-60

Jebel Nami: 54, 94, 95, 97,

Jebel Omori: 113(fn.1)

Jebel Otash: 36

Jebel al-Raqta: 125

Jebel Shalasi: 130

Jebel Si: 16, 20, 53, 54(fn.100), 57, 57(fn.5), 75, 75(fn.3), 86

Jebel Siab: 118

Jebel Silga: 33

Jebel Suruj: 88(fn.18)

Jebel Tageru: 125, 128-129

Jebel Taqali: 50, 50(fn.64)

Jebel Teiga: 60, 122(fn.6)

Jebel Tika: 95

Jebel Tréya (J. Thurraya): 77-78

Jebel Udru: 117

Jebel Um Kardos: 30, 53(fn.98)

Jebel Umm Qubu: 125

Jebel Wara: 33

Jebel Zankor – See Zankor

Jebel Zureiq: 21

Jebelein: 31(fn.4)

Jebelawi (Jebala, Jebelowi) Fur: 86, 87, 89

Jerash: 65, 65(fn.67)

Jernudd, B: 86

Jesus Christ (Nabi Isa): 136

Jews, Judaism: 15, 26(fn.38), 115, 136, 137

Jil Shikomeni: 111

Jinn-s: 79, 117

Joshua: 128

Juba II: 110(fn.3)

Juhayna Arabs: 129

Jukun: 26, 27, 135

Jungraithmayr, H.: 25, 29(fn.67)

Jupiter Ammon: 37(fn.54)

Jur: 23(fn.15)

Jura: 124

K

Kababish Arabs: 130(fn.96)

Kabbashi: 28

Kabkabiya: 28(fn.65), 88, 90

Kabushiya: 37(fn.46), 129(fn.78)

Kachifor, Sultan: 30

Kadama: 43, 55, 77, 77(fn.6)

Kaderu: 129(fn.78)

Kadmul: 47(fn.45), 48

Kadugli: 23, 23(fn.15), 75

Kagiddi – see Shelkota

Kai: 47

Kaiga: 112

Kaitinga: 25, 29(fn.71)

Kaga: 117

Kaja: 116(fn.4), 117

Kaja Seruj: 122, 123, 127

Kajawi: 123

Kalak Tanjak: 78

Kalamsiya: 38, 38(fn.60)

Kalck, Pierre: 112, 112(fn.26)

Kalga: 34

Kalge: 87(fn.9)

Kalokitting: 66(fn.76)

Kamadugu: 72

Kamal Yunis: 68(fn.88), 69(fn.101)

Kamala Keira: 97

Kamdirto: 119(fn.37)

Kamni: 96(fn.44)

Kamteinyi, Sultan: 28, 33

Kanem: 7, 12, 16, 22, 23, 26, 26(fn.39), 33, 44, 44(fn.8), 44(fn.13), 45, 46, 46(fn.27), 47, 47(fn.46), 48, 53, 56, 62, 63, 63(fn.47), 67(fn.86), 70, 72, 72(fn.130), 73(fn.143), 74, 80, 80(fn.1), 81, 84, 85, 111, 111(fns.11,12), 112, 118, 118(fn.24), 120, 122(fn.6), 128, 135, 136

Kanembu: 44, 44(fn.8), 46, 74, 80(fn.3), 111, 111(fns.11,12), 112, 119-120

Kano: 63, 77(fn.1)

Kanuri: 11, 16, 22(fn.4), 23, 28(fn.65), 44, 44(fn.13), 45, 46, 47, 47(fn.43), 54, 61(fn.33), 72(fn.135), 73(fn.142), 111, 111(fns.11,12), 112, 119, 128, 136

Kapteijns, Lidwien: 27

Kara: 27(fn.55)

Karakit Fur: 7, 86, 86(fn.4)

Karanga: 45, 77

Karanog: 124(fn.25)

Karkour-Nourène Massif: 44

Kas (Kusayr), King: 85

Kashemereh: 77

Kashémerém: 43

Kashmara: 25, 77

Kassala: 50, 52, 127(fn.58), 129(fn.78)

Kassifurogé, King: 30, 53(fn.98)

Katsina: 137

Kauara (Kawra) Pass: 20-21, 57

Kawar: 16, 22, 33, 45, 45(fn.25), 45(fn.25), 46, 46(fn.26), 47, 47(fn.46), 54, 120, 136

Kawka: 22

Kayra Fur: 10, 11, 11(fn.11), 12, 17, 18, 24, 29(fn.66), 31, 34(fn.25), 38, 43, 43(fn.3), 49, 50, 51, 55(fn.111), 59, 59(fn.15), 63, 64, 66, 69, 70, 75, 75(fn.3), 84-85, 86-109, 88(fn.21), 91(fn.2), 97(fn.45), 112, 120(fn.46), 131, 139-140

Kebeleh: 18-20, 18(fn.17)

Kedir, King: 27. 28

Kedrou: 129, 129(fn.78)

Kel Innek: 130

Kel Rela: 14, 14(fn.29)

Kella: 14

Kenen (Khanem), King: 85

Kenzi-Dongola: 120

Kerakirit: 75(fn.3)

Kerne: 78

Kerker: 60, 60(fn.18), 65, 118, 119-120, 122(fn.6)

Kerkur: 118(fn.27)

Kernak Wells: 125

Al-Kerri: 75, 75(fn.3), 126

Kersah: 129, 129(fn.78)

Khalaf, Sultan: 29, 29(fn.71), 30

Khamis Mubaju: 31(fn.9)

Kharadjites: 137

Khartoum: 8,

Khazars: 36(fn.44)

Kheir Ullah: 43

Khor Gadein: 123, 130

Khor al-Sidr: 125

Khouz: 73, 74, 128(fn.68)

Khujali bin ‘Abd al-Rahman, Faki: 88

Khuzam Arabs: 72(fn.128)

Khuzaym (Khoués), King: 85

Kilwa: 10

Kinin (see also Tuareg): 34(fn.29), 128

Kira: 47

Kirati (Kurata) Tunjur: 44, 47

Kirsch, JHI: 77

Kisra: 135, 135(fn.25)

Kitab Dali – see Law, Pre-Islamic

Knoblecher, Ignaz: 51(fn.74)

Kobbé: 4, 5

Kobbé Zaghawa: 88

Kobe: 94

Koc Col: 75

Kodoï: 45

Koenig, Dr A-M.: 29(fn.66), 30(fn.78), 88(fn.18), 100

Kolge: 88, 94(fn.21)

Koman: 128(fn.60)

Konda (Kidney feast): 97

Konnoso: 8

Konyunga Fur: 34(fn.25)

Kor, King: 29, 29(fn.66), 51

Kora (Korakwa): 7, 75(fn.3), 86(fn.4)

Kora Mountains: 54

Koran: 36(fn.44), 37, 50, 73, 89, 97

Kordofan: 23, 24, 24(fn.25), 25, 27, 27(fn.55), 28, 28(fn.58), 28(fn.65), 30(fn.78), 34, 49, 50, 50(fn.60), 50(fn.64), 52, 53, 64(fn.54), 66(fn.75), 70, 75, 82, 85, 87-90, 87(fn.9), 96(fn.41), 101, 110, 114(fn.12), 116(fn.4), 117, 117(fn.10), 118(fn.19), 119-120, 120(fns.46,48), 122, 123, 123(fn.12), 124-125, 125(fn.33), 127-131, 129(fn.86), 130(fn.96), 132, 135

Korkurma (Korgorma): 94(fn.21)

Koro Toro: 113, 132, 132(fns.5,7), 134-135, 134(fn.14), 140

Koro Toro Radiocarbon Dates: 138

Koseru (Kaseru), Sultan: 33

Kotoko: 63, 111(fn.11)

Kotor-Furi: 47(fn.46)

Kourdé: 77

Kreish: 8

Kropácek, L: 53, 72, 123

Kufic: 46(fn.37)

Kufra (Koufra): 4, 22, 26(fn.39), 31(fn.5), 77

Kujunung: 28

Kuka: 33, 59, 111-12, 111(fn.11)

Kuli (Kulli): 86, 88

Kulu: 64

Kulubnarti: 38

Kundanga: 78(fn.14)

Kunjara Fur: 45(fn.18), 62, 75(fn.7), 85, 86, 89-90, 97, 139

Kurds: 74

Kuroma, King: 51

Kurra: 59(fn.9)

Kurru: 47, 68, 123, 123(fns.15,16), 127

Kuru (Kurru), King: 28(fn.64), 31, 43, 84, 87, 93, 93(fn.10), 139

Kusbur (Kosber), King: 16, 28, 29, 31

Kush (Cush): 22, 23, 47, 113, 116(fn.4), 119, 123(fn.16), 127

Kush al-Wagilah (Kushah, Kus): 123

Kusi: 59

Kuttum: 9, 29(fn.71), 43, 54(fn.100), 119(fn.38)

Kutul: 117

Kwawang, Kunijwok: 75

L

Lagowa: 24

Lake Chad: 5, 26, 28(fn.65), 31(fn.5), 72(fn.129), 74, 111(fn.9), 114, 130, 132

Lake Esan: 35

Lake Fitri: 33, 45, 55(fn.111), 56, 110, 111, 111(fn.9), 111(fn.11), 112

Lampen, GD: 117

Lamtuna: 137

Lange, D: 73(fn.142), 110

Lango: 33(fn.12)

Largeau, Colonel: 6(fn.6), 73(fn.146)

Larymore, Constance: 136

Last, Murray: 22

Law, Islamic: 71, 71(fn.118,123)

Law, Pre-Islamic: 71, 71(fns.118,121)

Le Rouvreur, Albert: 36(fn.41)

Lebeuf, JP: 74, 77

Lemba: 15

Leo Africanus: 33, 110-112, 112(fns.20,21,25), 113, 137

Leucaethiopes: 16

Lewicki, T.: 22

Al-Libei, Sultan: 44

Libya, Libyans: 17, 34(fn.29), 37, 37(fn.53), 97

Libyan Desert: 117

Liguri: 23, 24

Litham: 43(fn.3), 45, 45(fn.25), 64(fn.53), 96(fn.44)

Locust Wizards: 34(fn.25)

Lol: 23(fn.15)

Lotuko: 33(fn.12)

Low, Victor: 12, 24,

Luniya Mountains: 136-137

Luwai ibn Ghalib: 26(fn.39)

Luxor: 38

Lwel: 75

M

Ma’at: 38

Maba: 44, 45, 74, 77(fn.9)

Mabo: 118(fn.28)

Macedonians: 37(fn.51)

Machina: 72

MacIntosh, EH: 27(fn.54), 30, 31,

MacMichael, Harold A.: 5, 12, 16, 22, 24, 27, 29(fn.71), 38(fn.57), 43, 43(fn.6), 49, 49(fns.55, 58), 52(fn.86), 53, 57(fn.5), 60, 62(fn.38), 64(fns.53,54,60), 65, 65(fn.61), 66, 66(fn.75), 67, 68, 70, 72(fn.129), 78(fn.14), 79, 85, 86, 96(fn.40), 116, 117, 120(fn.46), 128, 129(fns.77,86), 130, 130(fn.87)

Mace-heads: 130(fn.87)

Madala: 55

Madeyq: 68(fn.97)

Madi: 33(fn.12)

Magharba: 62, 62(fn.36), 63(fn.47), 70(fn.111)

Maghreb, (Maghrab, Maghrib): 20, 26(fn.38), 38, 39, 52, 62, 62(fn.36), 125(fn.33)

Magumi (Magomi: 16, 111, 111(fns.11,12)

Magyars: 36(fn.44)

Mahamid Arabs: 45, 89

Mahas: 117

Mahdiyya: 11(fn.10), 28, 36(fn.39), 87, 96, 116,

Mahmud al-Samarkandi: 24(fn.25)

Mahram: 16(fn.7)

Mai, King: 28

Mak Husayn: 38

Maiduguri: 74

Mailo Fugo Jurto: 30(fn.74),

Majala: 94

Majians: 128(fn.68)

Makada: 48

Makuria: 123, 140

Malakal: 31(fn.4)

Maledinga: 134

Malha City: 118, 119-120

Malha Crater: 116, 116(fn.1), 118, 118(fn.20), 119-120

Mali: 5, 115, 135

Malik al-Dubban: 97

Malik Kissinga Dora: 97

Malikite Mandab: 71, 71(fn.118)

Al-Mallagi: 125

Malumba: 136(fn.32)

Malwal: 23(fn.15)

Mamluks: 5, 62(fn.36), 129

Manawashi, Battle of: 62(fn.38), 96

Al-Mandar: 95

Mandara: 23, 46, 54, 63, 135-136, 136(fn.32)

Mandara Chronicle: 136, 137

Manjil: 38, 38(fn.57)

Al-Mansur Qala’un, Sultan: 52

Mao: 44, 45, 67(fn.86), 114, 118, 118(fn.24), 119-120, 119(fns.36,42), 120

Maqdum: 36, 36(fn.41)

Al-Maqrizi (Makrizi): 23, 126(fn.44)

Maranda: 22

Marawiyyun: 22

Ma’rib: 26(fn.38), 52(fn.78)

Masalit: 25, 43(fn.3), 64, 78(fn.14), 87

Masmaj: 55

Al-Mas’udi: 39

Matrilineal Succession: 46, 55, 56, 116, 118, 130, 130(fn.93)

Mauny, R: 112(fn.26), 134

Maydon, Major: 117

Mayram: 61(fn.33)

Mayri: 51

Mayringa Fur: 51

McCall, DF: 135, 135(fn.25)

Mecca: 28, 55, 62(fn.42), 71(fn.124), 72, 87, 136

Medes: 37(fn.52)

Meidob Hills, Meidobis: 18, 33(fn.18), 60, 60(fn.18), 116-121, 116(fn.4), 119(fn.38), 120(fns.46,48), 121, 122(fn.6), 128

Meidobi Burial Customs: 117(fn.11)

Meidobi King-Lists: 121

Meidobi Religion: 117-118, 117(fn.14)

Meidobi Sections: 116

Melik – see Malik

Memmi: 63

Merbo: 9

Merga: 46

Meroë, Meroitic: 8, 25, 26, 31, 31(fn.4), 46, 48, 54, 62, 112(fn.21), 113-115, 113(fn.1), 119, 122, 122(fn.6), 123, 124, 124(fn.29), 125, 127, 127(fns.51,56), 130, 132, 134-135, 140

Merri: 35, 36, 36(fn.45)

Michelmore, APG: 72(fn.129)

Missirya (Messiriya) Arabs: 50(fn.61), 72(fn.128)

Mihrab: 61, 66, 68-69

Mima (Mimi): 8, 25, 45, 55, 64, 64(fns.53,54)

Minbar: 68

Minos: 38(fn.58)

Mira: 50

Miri: 33

Misr Muhammad: 49(fn.59)

Mitnet al-Jawwala: 125

Moab: 128

Mockler-Ferryman, Major: 136

Modat, Captain: 112

El-Moghraby, Asim I.: 60(fn.18), 118-120,

Molu: 86, 87(fn.9)

Morocco: 14(fn.29)

Mohammed, Ibrahim Musa: 17, 69, 69(fn.101), 91(fn.5), 96(fn.40), 113, 120(fn.44)

Mondo: 44(fn.8), 80(fn.1), 81, 84, 85

Mongo-Sila: 23, 24

Mongols: 36(fn.44), 50

Morga: 63

Moro: 31(fn.5), 33(fn.12)

Moses: 37, 37(fn.51)

Muglad: 29

Al-Muhallabi: 22, 22(fn.4)

Muhamid Arabs: 55

Muhammad (Daju King): 29

Muhammad (Prophet): 28(fn.65), 71(fn.124), 110, 136

Muhammad ‘Ali: 30(fn.78), 62(fn.36), 73

Muhammad Bakhit, Sultan: 30

Muhammad Bello, Sultan: 36(fn.44)

Muhammad Bulad, Sultan: 27

Muhammad Bulat, Sultan: 88

Muhammad Dawra, Sultan: 88-89, 88(fn.23), 95-96

Muhammad Fadl, Sultan: 96

Muhammad Gunkul, Sultan (see Janqal)

Muhammad al-Hasin, Sultan: 49

Muhammad Husayn, Sultan: 95-96

Muhammad Ibrahim: 52(fn.77),

Muhammad Idris bin Katarkamabe, Mai: 70

Muhammad al-Ja’ali: 50(fn.64)

Muhammad Sayah: 118

Muhammad al-Shayb, Sultan: 44

Muhammad al-Shinqiti: 78(fn.15)

Muhammad bin Tamr: 119

Muhammad Tayrab, Sultan: 55(fn.111), 64(fn.54), 75(fn.3), 89-90, 95, 96, 97, 120(fn.46)

Muhammad Wad Tom, Shaykh: 129(fn.75)

Muhammad Yanbar: 119, 119(fn.36)

Al-Mu’izz ibn Badis: 52

Mujuf: 55

Mukarra (Mukurru): 37(fn.46), 46, 46(fn.31), 46(fn.35), 47, 47(fn.46), 52, 56, 127, 134

Mundara: 130

Munio: 46, 54

Al-Mur, Sultan: 55(fn.111)

Murdock, George Peter: 13

Murgi: 64(fn.54)

Murra: 95

Murtafal: 31(fn.6)

Murtal: 97

Musa, Sultan: 88, 94, 94(fn.21), 96, 96(fn.39)

Musa ‘Anqarib: 88-89

Musa Tanjar: 45, 45(fn.18)

Musa Um Ruddus, Shartai: 54(fn.100)

Musaba’at: 30(fn.78), 33, 49, 84-85, 84(fn.3), 85, 87-89, 97, 101, 103, 123, 131

Mustafa, Sultan: 24

Musulat: 63

Mutansir: 52, 52(fn.79)

Muwalih: 125

Muweileh: 125

N

Nachtigal, Gustav: 5, 13, 28, 28(fn.65), 31, 34, 44, 44(fn.8), 44(fn.13), 47, 47(fn.43), 49, 50, 53, 53(fn.91), 54, 55(fn.111), 57(fn.2), 57(fn.5), 71, 71(fn.121), 73, 75(fn.3), 75(fn.7), 77, 78(fns.14-15), 80(fn.1), 87(fn.9), 88, 91, 96, 102, 111, 118, 120(fn.46), 131

Nafer, King: 29

Nahas: 62, 62(fn.38), 87, 118

Na-Madu, King: 118-119

Nanku: 64(fn.53)

Napata: 26, 113, 127

Nari: 33

Nas Far’aon: 27, 27(fn.54)

Nassara (Nazarene): 73, 132, 140

Negib Effendi Yunis, Yuzbashi: 118(fn.19)

Nejran: 136

Newbold, D: 16, 61(fn.31), 117, 122, 122(fn.2), 123, 123(fn.13), 124, 124(fn.29), 125, 127(fn.57), 129, 129(fns.74,86), 130(fns.92,94)

N’Gazargamu: 72-73

Ngok Dinka: 23

Nguru: 73

Niamaton: 79

Nieke, Margaret R.: 11

Niger: 115

Niger (River): 110(fns.1,3), 136

Nigeria: 7, 13, 27, 44, 113, 114, 132, 136(fn.32)

Nikki: 136

Nilo-Saharan Language Group: 86

Nisba: 54

Njamena: 23

Nkole: 14

Noah: 28(fn.65), 128

Nobatia: 38

Nobiin: 120

Nok Culture: 114

Northern Rhodesia: 13

Noyo: 94

Nuba: 22, 23, 27(fn.55), 33, 33(fn.22), 50, 117, 118(fn.19), 122, 128-130, 136

Nuba Hills: 27, 120, 128

Nubia, Nubians: 11, 38, 43, 43(fn.6), 44(fn.13), 46, 46(fn.31), 46(fn.37), 47, 50, 52, 52(fn.86), 56, 64(fn.54), 65, 66, 67(fn.86), 68-69, 69(fn.102), 74, 97, 110, 112, 112(fn.21), 116-117, 118, 120(fn.48), 122-123, 123(fn.16), 124(fn.29), 126(fn.44), 129, 130-131, 132, 132(fns.6,7), 134-135, 137(fn.37), 139-140

Nubian Language: 116(fn.4), 120, 130(fn.92), 131

Nuer: 34(fn.26)

Nuh: 22

Nukheila: 22(fn.1), 127(fn.57)

Numan Fedda: 97(fn.45)

Nupe: 135

Nur Angara: 62(fn.38)

Nuri: 123(fn.16)

Nuwabiya: 123

Al-Nuwayri: 52

Nyala: 23, 24, 27, 27(fn.52), 28, 62, 62(fn.38), 75, 86

Nyèri: 45

Nyidor, Reth: 75

Nyikango: 75, 75(fn.5)

Nyolge (Nyalgulgule): 23, 23(fns.15, 19), 24, 29

O

Al-Obeid: 75, 88(fn.18)

O’Fahey, RS: 46(fn.31), 50, 56, 61(fn.33), 64(fn.57), 112, 112(fn.25)

Ogot, Bethwell A: 134-135

Ogra: 64

Olderogge, DA: 6

Omar Kissifurogé – see ‘Umar Kissifurogé

Omdurman: 62(fn.38), 116, 117

Oral Tradition: 10-15, 31(fn.6), 51(fn.69), 74, 75-76, 113, 129, 135, 139-140

Órre Baya: 57, 57(fn.2), 60, 95

Órre De: 57(fn.2), 60

Osiris: 8(fn.15)

Ostrich Eggs (decorative): 34, 34(fn.26), 36

Ottomans: 5, 24(fn.25), 74

Ounianga: 77

Ouogayi: 73(fn.148)

Oxyrinchus: 43(fn.6)

P

Paçir: 75, 75(fn.3)

Pahlavi: 135(fn.25)

Palestine: 65, 68, 128, 128(fn.68)

Palmer, HR: 7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 33, 46(fn.32), 48, 53(fn.90), 55, 72, 80(fn.1), 112, 112(fn.20), 128, 129, 135, 136, 137

Papadopoullos, T.: 135

Papyrus: 116(fn.1)

Parthians: 26(fn.38), 36(fn.44)

Patwac: 75

Pelpelle: 89

Penn, AED: 122-123, 122(fn.7), 126-127

Perari Kalga: 34

Perron, Dr.: 5

Persia, Persians: 26(fn.38), 37, 37(fn.52), 132, 134-135, 135(fns.21,25)

Petherick, J.: 52

Petracek, Karel: 119(fn.34)

Philae: 8, 33

Phoenicians: 115

Pilgrim Bottles: 124, 124(fn.29), 125, 127, 129, 129(fn.75)

“Platform of Audience”: 60, 61, 62, 65, 119

Pleiades: 78(fn.13),

Pliny the Elder: 16, 110(fn.3)

Pomponious Mela: 16

Pontiphar: 49(fn.58)

Potagos, Panyotis: 23

Pottery: 70, 122(fn.7), 123, 124, 124(fn.32), 132, 132(fn.5), 134, 134(fn.13), 140

Pre-Islamic Religion: 34, 86-87, 87(fn.9), 96(fn.38), 97, 117-119, 117(fn.14), 123, 136, 137

Prisons: 66, 66(fn.76), 93

Prophecy: 35

Ptolemy, Ptolemies, Ptolemaic Period: 16, 38, 43(fn.6), 127

Q

Qalaun, Sultan: 129

Al-Qalqashandi: 111(fn.12)

Qaqu: 22

Qarri (Querri, Gerri): 122, 125-127, 126(fn.44), 127(fn.46), 131

Qayrawan: 52, 125(fn.33)

Qays ‘Aylan: 38

Qelti al-Adusa: 129, 129(fn.73)

Qibla: 95

Qihayf, Battle of: 89

Qimr: 36(fn.43), 88

Qubba-s: 36(fn.41), 69, 95, 96

Quran – see Koran

Quraysh: 26(fn.39), 50, 50(fn.64), 102, 111(fn.12)

R

Radcliffe-Brown, AR: 7-8

Al-Rahad: 50

Rahaman: 26(fn.38)

Red Sea: 38, 63(fn.47)

Redjem: 118(fn.27)

Reisner, George A: 123

Reth: 75, 75(fn.2)

Reygasse, Maurice: 13-14, 20(fn.21), 118(fn.27)

Richards, Audrey I: 13

Rifa’a: 51

Rikabiya Ashraf: 130

Rizayqat Arabs: 89

Rizik (Rézik), King: 85

Ro-Kuri Region: 53, 95

Robinson, AE: 28, 29(fn.66), 38(fn.58)

Rodd, Francis R.: 130

Rome, Romans: 14, 26(fn.38), 37, 37(fn.52), 74, 114, 135, 137

Ronya: 59

Rosen, Georg: 77(fn.9)

Royal Platform: 59

Royna: 59(fn.12)

Rugman, Lady: 66-67

Rwanda: 115

Ryan, Bimbashi: 124(fn.32)

S

Sa’ad, Sultan: 44

Sabaloka Gorge: 126

Sabula: 57

Sabun: 75(fn.7), 91

Saccae: 63

Sadaqah: 97

Safia: 130

Sagava: 63

Saifawa Mai-s: 71

Salah, Sultan: 29

Salf (Zalf), King: 30

Salih (prophet): 28, 28(fn.65)

Salih ibn ‘Abdallah ibn ‘Abbas: 28(fn.65),

Salt Collection, Salt Trade: 116, 118, 120

Salt, Sir Henry: 86(fn.2)

Salua: 94

Al-Samarkandi: 50

Samarra: 65(fn.67)

Sambei: 27, 34(fn.25)

Sambella (Sambellanga): 64(fn.60)

Sania Kiri: 57

Samna: 33

San’a: 15

Sanam: 123(fn.16)

Sandstone Rings: 129–130, 130(fn.87)

Sanhaj Berbers (Sanhaja): 48, 125(fn.33), 128, 128(fn.68)

Sania: 123

Santandrea, P. Stefano: 29(fn.73)

Sanussis: 34(fn.29), 73, 73(fn.146), 74, 128(fn.68)

Sao: 31(fn.5), 63, 72, 111(fn.11)

Sarsfield-Hall, EG: 87, 117(fn.14)

Sassanids, Sassanians: 26(fn.38), 135

Sau: 55

Sa’ud: 28(fn.65)

Savonnier: 80(fn.2)

Sawwar bin Wa’il bin Himyar: 125(fn.33)

Sayf ibn Dhu Yazan: 26(fn.38), 111(fn.12)

Sayfawa: 16(fn.7), 111, 111(fns.11,12)

Schmidt, Peter R: 14

Scythians: 36(fn.44)

Sebakh, King: 129

Selatia: 62(fn.38)

Seleukos I Nikator: 37(fn.51)

Seligman, CG: 6, 7, 75(fn.2), 130(fn.87)

Selima Oasis: 46, 46(fn.37), 134

Seliquer, Captain: 132

Sendi Suttera, Iya Basi: 89

Serbung Masalit: 87

Serengiti: 60(fn.18), 118, 119

Sergitti: 79

Serra East: 68(fn.97)

Serra West: 67

Shabaka, King: 129(fn.79)

Shadow Sultan (see Kamni)

Shaffai Boggarmi, Dardai: 48(fn.51)

Shaheinab: 8

Shari’a – See Law, Islamic

Shartai: 34(fn.25)

Shatt: 23, 23(fn.15), 24, 29

Shau al-Dorsid, Sultan: 16, 27, 30, 30(fn.74), 44(fn.15), 48, 50, 51, 53-54, 56, 57-64, 57(fn.5), 59(fn.15), 61(fn.32), 62(fns.36-37), 70(fn.111), 72, 75, 75(fn.3), 84-85, 87, 96(fn.41)

Shaw, WBK: 123-124, 124(fn.25), 127(fn.57)

Shelkota Meidob: 116, 116(fn.4), 121

Shendi: 27, 27(fn.53), 28(fn.65), 30(fn.78), 125(fn.37)

Sherkayla: 50

Shilluk: 8(fn.15), 34(fn.26), 75, 75(fn.2), 123

Shimir: 55

Shinnie, Peter: 11, 13, 67, 67(fn.86), 73(fn.144), 74, 113, 113(fn.1), 127, 127(fn.56), 132, 135

Shirim: 88

Shoba: 90

Showaia: 96(fn.38)

Showunga Tunjur: 59

Shu (Egyptian God): 54

Shuqayr, Naum; 89

Shuwa Arabs: 44

Si Dallanga: 54

Siesa: 71

Sigato: 119

Sikar: 91

Simiat Hills: 33

Sinnar (Sennar): 5, 27, 27(fn.55), 28(fn.65), 30(fn.78), 38(fn.58), 43, 87, 88(fn.18), 89(fn.28), 126, 126(fn.44), 129

Sira al-Hilaliya: 49

Sitting Burial: 31(fn.5), 119(fn.42)

Sira al-Hilaliyya: 49

Sirma: 59

Slatin Pasha, Rudolf: 1, 29, 51, 78(fn.14)

Slaves, Slavery: 27(fn.55), 34, 71, 87-89, 96, 120(fn.46), 140

Snakes in Religious Rites: 78-79

Soba: 62(fn.36), 65(fn.67), 66, 122, 123, 124, 124(fn.29), 126-127, 126(fn.44), 127(fns.47,56), 131

Sobat River: 31(fn.4), 75

Solomon: 39

Songhay: 135

Songs: 80

Sopo River: 23

South Africa: 15

South Sudan: 35

Spain, Spanish: 54, 110, 137

Spaulding, Jay: 50, 64(fn.57), 112, 112(fn.25)

Stevenson, RC: 23

Stewart, Andrew: 38

Stone Circles: 118(fn.27), 124, 129

Stone Worship: 61(fn.30), 72, 72(fn.129), 86, 87(fn.9), 117-119, 139

Suakin: 127(fn.58)

Subhanin: 25, 25(fn.29)

Sudan Notes and Records: 7, 8

Sudan Political Service: 7, 8

Sufyan, King: 85

Sufyan al-Thawri: 37

Sulayman (founder of Bilia Bidayat): 48

Sulayman al-Abyad: 89

Sulayman Solong (Sliman, Solongdungo), Sultan: 43, 55(fn.111), 59, 59(fn.15), 70, 70(fn.111), 78(fn.14), 87-88, 89, 93, 93(fn.10), 94-96, 96(fn.41), 118, 120(fn.46), 131, 139

Sun Worship: 77(fn.9)

Sunghor (Sungor): 36(fn.41)

Suni Valley: 94

Supreme Court of Canada: 14-15, 15(fn.33)

Syria. Syrian: 50, 68

T

Taberber: 28(fn.64)

Taboos: 96(fn.38)

Tabun, Shartai: 31

Tagabo Hills: 116-119, 119(fn.36), 119(fn.38)

Tahir, Basi: 28

Tahrak, King: 129

Taiserbo: 31(fn.5)

Taitok: 14, 14(fn.29)

Tageru Hills: 128

Taharqa, King: 129(fn.79)

Tajia (Tagia): 38(fns.57-58)

Tajuwa: 22-23, 33, 112(fn.20)

Takaki (Tekaki): 66(fn.76), 71(fn.120)

Tari: 134

Al-Taka: 129, 129(fn.78),

Takamat: 13-14

Tama: 27(fn.31), 36(fn.41), 45(fn.21)

Tamachek: 45(fn.25)

Tamurkwa (Tamurka) Fur: 86, 86(fn.4), 87

Tanit: 14

Tanjak: 55

Tanjikei: 36(fn.41)

Tanzania: 10, 115,

Tar Lis (Tarlis): 112

Tari: 132

Taruga: 114

Tartari: 135

Tatars: 36(fn.44)

Al-Tayeb, Shaykh: 29(fn.66), 99

Tchertcher Mountains: 128(fn.68)

Tebeldi Trees: 3-4, p.3 (fn.5)

Teda: 16, 16(fn.5), 22, 22(fn.4), 34(fn.29), 45, 47, 47(fn.45), 48, 48(fn.47), 119, 128

Tedagada: 45

Tedjeri (Tejeri): 119(fn.41)

Teiga Plateau: 117

Tamaragha Doka, Shaykh: 129(fn.81)

Temeh: 45(fn.21)

Ten Tribes of Israel: 36(fn.44)

Termit: 113

Terninga, Sultan: 27

Teqaqi: 71

Tesseti Dynasty: 116

Thamud: 28(fn.65)

Thelwall, Robin: 117, 120

Thurro: 75

Thutmosis III: 46, 46(fn.35), 134

Thutmosis IV: 8

Tibesti (Tu): 5, 8, 16, 20, 31(fn.5), 45, 45(fn.23), 46(fn.32), 47, 47(fn.46), 48, 48(fn.51), 54, 64(fn.58), 113, 119, 128(fn.68), 130, 136-137

Tibet: 35

Tidikelt: 14(fn.29)

Tidn-Dal Language: 116

Tié: 67(fn.86), 73, 73(fn.144), 74

Tifinagh: 14, 70, 70(fn.108)

Tilho, Commandant: 77, 132, 132(fn.4)

Timsah: 28(fn.64)

Tin Hinan: 13-14 13(fn.25), 14(fn.29)

Tine: 88, 94(fn.21)

Tirga umm sot: 33, 33(fn.18),

Tit: 20(fn.21)

Tiv: 13

Togoland: 5

Togonye, Togoinye: 34, 34(fn.25)

Tong Kilo: 94, 97(fn.46)

Tong Kuri: 93

Tongoingi (Togoingi): 34(fn.25)

Tora: 16-21, 31, 33, 44, 53, 57, 59, 60, 61, 62, 64, 65, 66, 72, 90, 91, 91(fn.5), 94, 95, 95(fn.31), 97, 119, 123, 126, 127, 128, 128(fn.68), 131

Toronga Kuroma: 16, 17-18

Torti Meidob: 116

Toschka: 134

Tounjour Wells: 132, 132(fn.6)

Tow: 54

Transmogrification: 86,

Treinen-Claustre, F: 134

Tréya (see Jebel Tréya)

Trigger, Bruce: 8, 120

Tripoli: 4, 60, 63(fn.47), 70(fn.111), 77, 77(fn.1), 117, 137

Tuareg (see also Kinin): 13-14, 34(fn.29), 36(fn.44), 43(fn.3), 45, 46(fn.32), 64(fn.53), 128, 130, 130(fns.93,96)

Tubba Kings: 38, 111(fn.12)

Tubiana, J.: 43, 63

Tubu (Tibu, Tibbu): 16, 27(fn.54), 34(fn.29), 44, 44(fn.8), 45, 46, 46(fn.27, 30, 31), 47(fn.46), 48(fn.51), 49, 56, 64(fn.53), 75(fn.3), 117, 130, 137, 139, 140

Tubu Genealogy: 47(fn.46)

Tukl: 20, 61(fn.31), 65-66, 69

Tumaghera: 45-48, 45(fn.25), 46(fn.26), 46(fn.31, 32), 47-48, 47(fn.43), 47(fn.46), 48(fn.51), 54, 113, 140

Tumaghera of Tibesti, Sections: 47, 47(fn.46)

Tumam Arabs: 8

Tumsah (see Tunsam)

Tuna: 59

Tunis: 20, 36(fn.41), 44, 49, 50, 52, 63, 77(fn.1), 80

Tunis (Kanem): 80(fn.1)

Tunisia: 20(fn.22), 52, 73, 74

Al-Tunisi, Muhammad ‘Umar: 5, 27(fn.55), 28(fn.65), 37(fn.54), 43, 57(fn.2), 64(fn.53), 72(fn.134), 77(fn.9), 120(fn.46)

Tunjur: 5, 10, 12, 16, 18, 25, 26, 28, 28(fn.64), 28(fn.65), 29(fn.71), 30, 30(fn.74), 31, 33, 34(fn.25), 36(fn.41), 43-85, 43(fn.6), 44(fns.8, 15), 45(fn.18), 45(fn.19), 46(fn.31), 47(fn.46), 48(fn.47), 48(fn.53), 48(fn.54), 51(fn.71), 52(fn.86), 53(fn.90), 55(fn.111), 57(fns.2,5), 59(fn.15), 62(fn.37), 62(fn.42), 63(fn.47), 72(fn.128), 75(fn.3), 77(fn.6), 80(fns.1,2), 84(fn.3), 87, 88, 88(fn.21), 91, 95, 97, 111, 111(fn.11), 112, 113, 118, 119, 120(fn.46), 131, 132, 132(fn.6), 134, 139

Tunjur, Sultan: 30, 43

Tunjur-Fur: 43, 64(fn.60), 70

Tunjur of Kanem, Sections: 44(fn.13)

Tunjur King-Lists: 81-85

Tunjur Language: 44(fn.8), 63, 64(fn.54)

Tunjur Sections (Darfur): 43

Tunjur Wara: 59

Tunsam (Tumsah), Sultan: 28(fn.64), 31, 49, 70, 84, 87, 89, 93, 93(fns.8,10), 139

Tura: 47

Turco-Egyptians: 12, 62(fn.36)

Turi: 54, 57(fn.1)

Turks (see also Ottomans, Turco-Egyptians): 36(fn.44), 63, 70(fn.111), 74

Turkish Language: 74, 77(fn.9)

Turra: 16, 18, 27, 53, 57, 59, 69, 70, 91(fns.2,3), 93(fn.8), 95-97, 96(fn.43), 97(fn.45), 97(fns.46,47), 99

Turra Hills: 91

Turti: 35

Turrti Dynasty: 118, 121

Turuj: 8, 27(fn.55), 33

Turza: 120(fn.46)

Al-Tuwaysha: 119

U

Ubangi River: 110(fn.3)

Udal, John O.: 75, 75(fn.3)

Uddu: 86

Ufa, King: 29

Uganda: 14, 18

Um Bura: 64(fn.53)

Um Bus Masalit: 78(fn.14)

Um Daraj (Durraj): 129-130

Um Kurdoos: 28

Umangawi: 78(fn.14)

‘Umar, Daju King: 28

‘Umar, Tunjur Sultan: 77

‘Umar ‘Ali: 45

‘Umar Kissifurogé: 28, 29-30, 33

‘Umar Lel, Sultan: 27, 89, 95

‘Umar ibn Muhammad Dawra – see Muhammad Dawra

Umm Kiddada: 119

Umm Harraz: 94

Umm Harot: 125

Umm Shaluba: 73(fn.148), 77

Ummayads: 48, 49, 51

Umunga Fur: 33

Upper Nile Province: 34(fn.26)

Uri: 27, 28(fn.64), 44, 56, 57, 57(fns.2,5), 59, 60-64, 60(fn.23), 60(fn.24), 61(fn.30), 62(fn.37), 63(fns.46,47), 64(fn.58), 65(fn.65), 68-69, 70, 70(fn.111), 72, 73, 74, 93, 112, 112(fn.21), 119, 119(fn.38), 122(fn.6), 139

Urimellis: 64

Urti Meidob: 116, 121

V

Venda: 15

Vansleb, JM: 64, 112(fn.25)

Vantini, G: 134

Vatican: 137

Veil – see Litham

Venice, Venetian: 63, 63(fns.47,49)

Vienna Manuscript: 51(fn.74)

Vogel, Dr. Edward: 78

W

Wadai: 5, 8, 21, 25, 26, 27, 27(fns.54,55), 28, 28(fn.65), 28(fn.65), 33(fn.18), 34, 36(fn.41), 43, 44, 45, 45(fn.21), 46, 48, 48(fn.53), 48(fn.54), 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57(fn.2), 59, 62, 64(fns.53,54), 71, 72(fns.128,129), 74, 75(fns.3,7), 77-79, 77(fns.1,6), 83, 86, 88-89, 95, 110, 111, 111(fn.11), 112(fn.24), 120(fn.46), 128, 132, 134, 135, 140

Wadai, Aboriginal groups: 25

Wadi Abu Dom: 134

Wadi Abu Hashim: 125

Wadi Abu Sibaa: 124

Wadi al-Anaj: 127(fn.57)

Wadi Barei: 94(fn.21), 95

Wadi Golonut: 118

Wadi Halfa: 8, 68(fn.97)

Wadi Hawar (Howar): 4, 9, 47, 125

Wadi Howa: 77

Wadi Jeldama: 95

Wadi Jugtera: 64(fn.53)

Wadi Magrur: 117

Wadi al-Melik (Milk): 4, 117, 122(fn.6), 123, 125, 127

Wadi al-Mukaddam (Muqaddam): 117, 125

Wadi al-Sabt: 38

Wadi Tunsam: 93

Wadi Umm Shaluba: 44

Wadi Uri: 64(fn.58)

Wahb bin Munabbih: 6, 37, 37(fn.52)

Al-Wahwah: 37(fn.46)

Walool: 126

Walz, Terrence: 54

Wamato: 119(fn.37)

Wandala: 136(fn.32)

Wansborough, John: 11

Wara: 33(fn.18), 43, 45, 55, 59, 74, 77-79, 77(fn.6)

Wastani: 36(fn.41)

Wathku: 23

Wau: 23(fn.15)

Wawat: 8

Western Field Force: 1-2

White Nile: 31(fn.4), 50

Wickens, GE: 18-20

Wirdato Meidob: 116, 118

“Wise Stranger” (see also Ahmad al-Ma’qur): 10, 28(fn.65), 29(fn.73), 46, 48, 49-52, 50(fn.64), 56, 87, 119

X

X-Group: 124(fn.29)

Y

Yahia: 27(fn.31)

Yame: 28(fn.65), 43

Yao: 111(fn.11)

Ya’qub ‘Arus, Sultan: 88

Ya’qub Bok Doro, Sultan: 30

Al-Ya’qubi: 22, 128

Yaqut bin ‘Abd Allah al-Hamawi: 22(fn.4)

Yasir: 39

Yemen: 25, 26, 26(fn.38), 29(fn.73), 37, 38, 49, 111(fn.12), 125(fn.33), 136

Yér: 27(fn.55)

Y’nk: 128

Yusuf, Prince: 89

Yusuf As’ar Yath’ar (Dhu Nuwas): 26(fn.38), 136

Z

Zaghawa: 22, 22(fn.4), 23, 23(fn.8), 25, 27, 29(fn.71), 36(fn.41), 49(fn.55), 50(fn.67), 63-64, 64(fn.53), 72(fn.128), 77, 88, 89, 112(fn.20), 114(fn.16), 119, 136

Zaghay: 23

Zakaria: 69

Zalaf, King: 28, 29

Zalingei: 86

Zanata Berbers: 49,

Al-Zanati, Khalifa: 49

Zanj: 22, 23, 23(fn.8)

Zankor: 66(fn.75), 122-123, 122(fns.2,6), 123(fn.13), 127, 127(fns.53,56), 130, 131, 134

Zarroug, Mohi al-Din Abdalla: 127

Zayd: 36(fn.41), 51

Zayadiya Arabs: 36(fn.41), 51

Zayn al-‘Abidin de Tunis: 77(fn.9)

Zeltner, Jean-Claude: 44

Zenata: 128(fn.68)

Zeugatania: 137

Zeus Ammon: 37-38

Zhylarz, Ernest: 46(fn.35), 120(fn.48)

Ziegert, H: 9

Zingani: 137(fn.37)

Al-Zubayr Pasha: 11(fn.10), 12, 62(fn.38), 87, 96

Zurla: 63