Aberfoyle International Security Analysis

Monograph Series no. 1

Andrew McGregor

December 2002

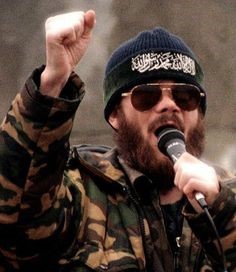

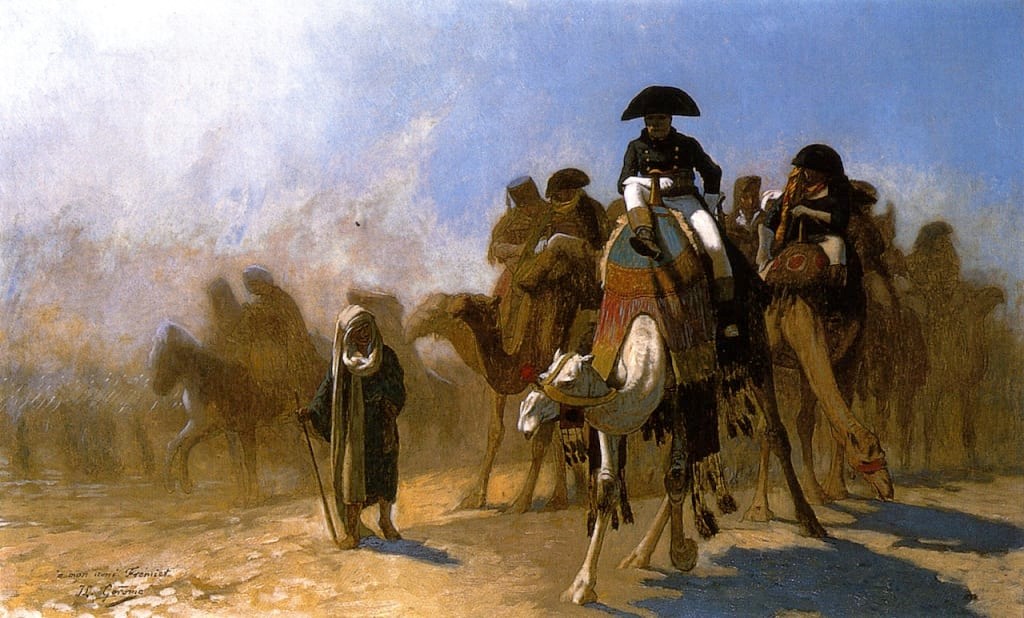

Salman Raduyev before his disappearance

Salman Raduyev before his disappearance

Salman Raduyev after extensive facial reconstruction

Salman Raduyev after extensive facial reconstruction

One of Russia’s most wanted men was sentenced to life in prison in December 2001 after a sensational and controversial trial. Field Commander Salman Raduyev, one of the strangest characters to hit international headlines in recent years, was convicted of a host of violent crimes, including terrorism, pre-meditated murder, hostage-taking, banditry, leading an armed group, and ‘organizing explosions’. Raduyev was described during the trial by Russia’s Prosecutor-General as ‘the Chechen Bin Laden’. There remain many unanswered questions about Raduyev’s sudden death in prison after his conviction. Many Chechens as well as Russians are glad to be rid of the erratic field commander, who has in the past threatened to strike Russia with chemical weapons. Raduyev, who underwent radical plastic surgery in 1996, was captured in early March of 2001 in a house well behind Russian lines. The operation was carried out by a special anti-terrorist strike-force of the FSB, the successor to the Soviet Union’s KGB.

The ever-slippery Raduyev had already pulled the trick of returning from the dead, but after his conviction he faced the living death of a life sentence in a Russian penitentiary. Raduyev often presented the world two faces: Chechen patriot or Russian provocateur? Or was Raduyev just a charismatic if ‘creepy’ madman who manipulated the political chaos and clan ties of Chechnya to rise far above his capabilities? Many who knew him well would agree to the latter, noting that he was unknown before he became son-in-law to the late Dzhokar Dudayev, the first Chechen president. Russian prosecutors simply say that Raduyev was a clever and cold-blooded terrorist. All that is certain is that at some point Raduyev decided he was going to become famous, and he succeeded, as Russia’s most wanted man.

The ever-slippery Raduyev had already pulled the trick of returning from the dead, but after his conviction he faced the living death of a life sentence in a Russian penitentiary. Raduyev often presented the world two faces: Chechen patriot or Russian provocateur? Or was Raduyev just a charismatic if ‘creepy’ madman who manipulated the political chaos and clan ties of Chechnya to rise far above his capabilities? Many who knew him well would agree to the latter, noting that he was unknown before he became son-in-law to the late Dzhokar Dudayev, the first Chechen president. Russian prosecutors simply say that Raduyev was a clever and cold-blooded terrorist. All that is certain is that at some point Raduyev decided he was going to become famous, and he succeeded, as Russia’s most wanted man.

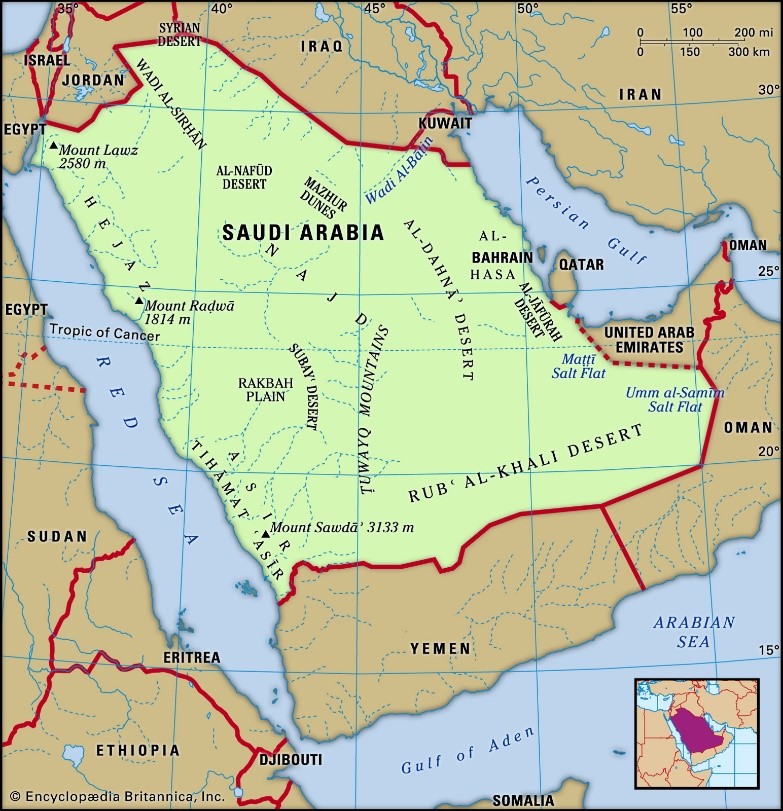

The mysteries behind Salman Raduyev’s career are a reflection of the bizarre world of shadows in which Chechens live. Since the tiny Muslim nation of under a million people attempted to secede from the crumbling Soviet Union in 1991, it has endured economic blockades and two brutal wars with Russia, the latest still ongoing. After the failure of the Federal Army to subdue the Chechens in 1996 (following the first Chechen war), responsibility for Chechnya passed into the hands of Russia’s alphabet soup of security services, each conducting covert operations reporting to a different ministry. With unemployment reaching 90% in post-war Chechnya, young men sought any means of supporting themselves and their families. Options were few; kidnapping gangs were particularly lucrative, as was oil theft. ‘Oil moonshiners’ turned their backyards into cottage industry oil-wells, causing so much damage that the capital Grozny now floats on a layer of oil and is environmentally unstable, though tens of thousands still dwell in the ruins of the battered city. Russian money was always there for the taking, in return for certain services, of course. Most of these services involved the continued destabilization of the upstart nation. Many of the most notorious kidnappers seemed to have Moscow connections, and Chechnya became a kind of clearing-house for kidnapping victims who were often seized far from Chechnya before being delivered there to await ransom. Money also began to flow from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the Persian Gulf Emirates. Most of these funds were also given conditionally, intended to further the spread of Saudi-style reform Islam in the Northern Caucasus. This was the era of the ‘Field-Commander’, veteran leaders of the first Chechen war who acted as semi-official warlords while moonlighting as bandit chiefs. Most of the money in Chechnya passed through their hands at some point, giving them immediate power in a desperate land ruled by a penniless government.

In this atmosphere many strange and ruthless characters flourished. One such was ‘Khalifa’ Adam Deniyev, leader of a cult-like religious movement who demanded that the sacred Ka’aba shrine in Mecca be moved to Chechnya. Deniyev was also a self-confessed leader of a murderous kidnapping gang, and seems to have been on the payroll of at least two Russian intelligence agencies. After being promoted by the Russians as the new puppet leader of Chechnya in spring 2001, Deniyev was blown up in the middle of making a live television broadcast. Arbi Barayev was another killer who found his calling in the Chechen conflicts. Leader of a major gang after the first Chechen war, Barayev established himself as the most militant of the Islamists, while feuding almost continuously with the Chechen government and other field-commanders. The efficient use of urban bombings and assassination squads were Barayev’s specialty, skills which made Barayev’s services appealing to friend and foe alike. Strangely enough, Barayev lived through most of the current war in his own house, just down the road from a Russian police station. Before his death in the Spring of 2001, there was growing evidence that Barayev was working for both the Russians and the Gulf State Islamists.

Surely, however, the strangest of the Chechen field-commanders was Salman Raduyev, a once-powerful warlord with thousands of men under his command. Although Raduyev was said to be in poor health and played only a small role in the present war, his capture was announced personally by a triumphant Vladimir Putin. The arrest of the man Putin called ‘an animal’ came only days before Putin’s election as Russia’s new president, and provided a lone success for Putin in his efforts to subdue the stubborn Chechen mujahidin before the election. Russian intelligence agents and assassination squads have resolutely pursued the military and political leadership of the Chechen rebellion since 1999, but the 34 year old Raduyev was the first figure of any significance to be taken alive. Like the other Chechen warlords, Raduyev was frequently but prematurely declared dead by Kremlin spokesmen. At one point Russian television even showed a grave alleged to be his.

Raduyev was once widely accused of being behind the 1999 apartment bombings in Moscow that killed over 300 people, though a number of other suspects (all non-Chechen residents of the North Caucasus) were committed to trial by Russian authorities for indirect involvement. [1] These trials were held in secret, with all security for prosecutors and defendants alike carried out by the FSB, despite the FSB itself being a major suspect in the bombings in the minds of many Russians. State prosecutors initially declared that Raduyev’s trial would also be held in secret, no doubt because of the possibility for government embarrassment, but a decision to allow press coverage was made at the last minute. Circumstances had changed since September 11, and the Russian government was now eager to have maximum publicity for the trial of a Chechen ‘terrorist’ as part of their campaign for Western acceptance of Russian methods in Chechnya.

Rebellion and Deportation

In a world that has seen countless small ethnic groups disappear or become fully assimilated over the last two centuries, the tiny Chechen nation has simply refused to be destroyed. Since the reign of Peter the Great nearly three hundred years ago, generation after generation of Chechens have risen up against the occupation forces of mighty Russia. As each rebellion inevitably fell before the military weight of Russia, the remaining Chechens set about re-arming and building large families to replace the terrible civilian losses and create a new generation of fighters. The Chechen symbol is the She-Wolf that legend tells gave birth to their nation, and Chechen fighters have been known to terrify their enemies with wolf howls before launching an attack.

In the midst of yet another Russo-Chechen war, it is now hard to believe that in 1944 there were virtually no Chechens living in Chechnya. Incensed by yet another uprising in Chechnya in the early 1940s (the Israilov insurrection), Stalin angrily denounced the Chechens as German collaborators on slim evidence (the German offensive had barely touched Chechen territory), and ordered the entire nation deported to Central Asia. In a massive but highly efficient operation undertaken by Beria’s NKVD, the Soviets loaded all the Chechens, Ingush (a related people) and many neighbouring Muslim groups into boxcars and cattle-cars without food, and only the possessions they could carry. [2] Ironically, the operation was carried out with some ease because most young Chechen men were at the front fighting the Germans (when the war was over the Chechen veterans were decorated and deported to Central Asia). Those that survived the one month journey to Kazakhstan were offloaded onto the barren Central Asian steppe, without food or shelter. Some survived by eating grass, while others went mad. Instead of giving up, the Chechens reunited, and began organizing to preserve the Chechen nation in exile. Aleksander Solzhenitsyn met many Chechens during his own exile in the Soviet Gulags, and was astonished by the Chechen refusal to submit. [3] The exiled Chechens maintained an open and constant hostility to their supposed Soviet masters, who soon came to fear the Chechen exiles. [4]

While the Chechens struggled in Central Asia, Stalin’s men began to eradicate every trace of the Chechen nation. Books and mosques were burned, references to Chechens removed from history texts, and ethnic Russians were imported to fill the Chechens’ empty homes. In their zeal the Russians even removed all the tombstones from the graveyards. The Chechens began filtering back into their homeland after Krushchev’s reforms of 1956, and began to gradually buy or pressure the Russians out of Chechnya. By the end of the Russo-Chechen war of 1994-96, nearly the only Russians left in Chechnya were ancient pensioners in Grozny who could not afford to leave the devastated Chechen capital. The period of the deportations formed a watershed event in the lives of most Chechens. Many senior Chechen leaders, such as President Maskhadov, were born into the Central Asian exile. The betrayal of their people by the Russian authorities can never be forgotten by the Chechens, and the event forms the poisonous bottom-line for all political arguments within Chechnya – ‘No matter what Moscow offers, how can we trust them? If we surrender our weapons, who will prevent the next deportation?’ Revenge and retribution are important concepts in the honour-conscious Caucasus Mountains and can be used to justify a wide variety of violent acts. One man’s terrorism is another man’s blood-revenge.

Little has changed in the present war; beyond making little distinction between civil and military targets, the Russians now regularly destroy the centuries-old feudal towers and Sufi shrines that dot the Chechen landscape. Oddly enough, they are now supported in this by the new wave of Saudi-influenced Islamists who seek to destroy the Sufi orders and rituals that dominate Chechen life. [5]

The Emergence of an “Arch-Terrorist”

Salman Raduyev burst into the headlines of the international press with an audacious strike in January 1996 on the Russian military base at Kizlyar in Dagestan, far behind the Russian front line. At first the strike appeared to emulate Field Commander Shamyl Basayev’s 1995 raid on Budennovsk, but the operation quickly fell apart and was ultimately nearly as disastrous for the Chechens as for the Russians. The raid, initially intended to eliminate a Russian helicopter base in Kizlyar, may have represented an attempt by the late Chechen President Dudayev to reassert his pre-eminence among the rising stars of Basayev and Aslan Maskhadov, his two chief military commanders. American security advisor Yossef Bodansky has claimed that the operation was planned by an expert Pakistani ‘Afghan’ (a veteran of the international Islamist volunteer force in the Afghan war of the 1980’s), but in execution the operation displayed all the traits of impetuosity and inexperience that characterized Raduyev at the time. The former Communist Youth leader’s only other leadership role was in a four-day seizure of Gudermes in December 1995, but the whole operation had been planned by Maskhadov.

Colonel Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov

Colonel Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov

It appears that when the attack on Kizlyar began to fall apart, Raduyev was forced to acknowledge his shortcomings, and effective command of the rebels passed temporarily to a more capable commander, Colonel Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov. A veteran of the Abkhazian campaign and Basayev’s raid on Buddenovsk, a reluctant Israpilov had only joined the raid after all the men in his command signed up. Now he took a page from Basayev’s tactics at Buddenovsk and seized a hospital, taking thousands of hostages. Within hours the Russians attacked, causing many casualties amongst the hostages. The situation was spiraling out of control. Israpilov used a policeman’s walkie-talkie to demand that the Russian attack cease or he would begin shooting hostages. The policeman found Israpilov’s efforts amusing. According to Israpilov, ‘I kept telling him I would shoot him. He was not paying attention, he was smiling, I could see he did not believe me. I shot him in the forehead. I was demanding that they hold their fire. After that they did’. [6]

The situation now in hand, Raduyev re-took command, and negotiated a withdrawal to the Chechen border with Daghestani politicians. The rebel column would consist of 128 hostages in 11 buses and 2 trucks, including seven Daghestani government ministers who volunteered to go as hostages. The Russians, however, decided to destroy the column the moment it crossed the Chechen border (thus sidestepping commitments given by the Daghestani government that the column would not be attacked). The Russian attack was poorly coordinated, and the Chechens hastily reversed their column, heading back to the tiny village of Pervomaiskoye, across the Daghestani border. On arrival, the rebels took 37 militiamen captive, as well as a stockpile of arms and munitions. Negotiations began anew, but the Russians were moving in a force twenty times the size of the rebel group. Five days passed before the Chechens, believing an attack to be imminent, released the women, children and politicians.

When the Russian attack did begin, it became clear that the planners had no interest in trying to rescue the hostages, who were initially positioned as a shield for the rebels. Field artillery and enormous Grad rockets pounded the village, while helicopters worked in close with missiles and machine gun fire. As the three -day attack began, the FSB was reporting that the Chechens had already killed all the hostages. The intensity of the barrage suggested that the Russians were not concerned about contradictory accounts emerging from the ruins of Pervomaiskoye. Repeated ground attacks by elite Russian soldiers and anti-terrorist units were repelled with heavy losses, as the Chechens constantly shifted their heavy machine-guns. The Chechens also succeeded in listening to Russian radio communications, giving them a chance to take shelter before artillery barrages began. Surrender was no longer an option, and the besieged Chechens fought to the death. Russian troops fell by the score as their own artillery and missiles crashed into their positions. Ahead of them was a withering fire from the entrenched Chechens.

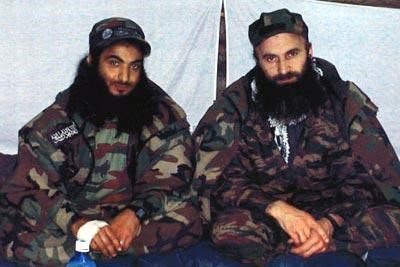

Amir Ibn al-Khattab (left) and Shamyl Basayev (right)

Amir Ibn al-Khattab (left) and Shamyl Basayev (right)

Despite Russian losses, they, unlike the Chechens, had recourse to unlimited manpower and munitions. Chechen losses were building, and it was difficult to replace Chechen fighters. The Chechens repulsed twenty-two attacks over an eighty-two hour period. By January 17, it became apparent that only a desperate breakout could save any of the fighters and their hostages. The latter were no longer guarded, as the Russians were shooting at anything that moved. Maskhadov and Basayev launched hundreds of fighters on diversionary attacks in Daghestan to draw Russian forces away. The Chechen fighters and hostages began to move out of Pervomaiskoye in groups. Many were lost to mines and Russian fire. Some fighters volunteered to stay behind to cover the retreat until they were killed. It appears that these men continued resistance into the next day. Some hostages carried out wounded fighters, while others carried rifles to defend themselves from their supposed rescuers. Over sixty fighters were lost in the withdrawal.

Raduyev’s raid had international reverberations. In Trabazon, Turkey, a commando force led by Mohammed Tokçan seized a Turkish ferry carrying several hundred people, mostly Russians. Tokçan was a former comrade-in-arms with Shamyl Basayev in the North Caucasian volunteer force that fought for the separation of Muslim Abkhazia from Georgia in 1992-93. He demanded the Russians allow Raduyev’s force to leave Pervomaiskoye or the ship would be destroyed. The Turkish security forces resolved the hijacking peacefully, but Salman Raduyev had finally made it. He didn’t realize it at the time – under continuous Russian fire, his world had become very small – but Salman Raduyev was now an international figure. His name was on the front page of all the international press, and Raduyev later discovered he liked the way it looked. Though Kizlyar made his reputation, it was the last operation of any importance that Raduyev would carry out. In the violent world of the North Caucasus, Raduyev found that there were plenty of unclaimed yet spectacular crimes that he could attach his name to in order to stay in the headlines.

ChRI President Aslan Maskhadov

ChRI President Aslan Maskhadov

Maskhadov and Basayev were both furious that Raduyev had carried out an unapproved operation (at least as far as they knew), and that they had further been required to commit considerable manpower and resources to bail him out. Though the Russian army had been badly embarrassed, Raduyev had lost ninety-six valuable fighters on a raid with no tangible results. Raduyev had also made many dangerous enemies with his raid, both in Daghestan and Russia.

Three other fighters from the raid on Kizlyar, Turpal-Ali Atgeriyev, Aslanbek Alkhazurov and Khuseyn Gaysumov stood trial alongside Raduyev. Atgeriyev became State Security Minister in the post-war Chechen government and was later one of President Maskhadov’s closest allies, responsible for his personal security. As a result of his responsibilities as State Security Minister Atgeriyev had many contacts with the FSB, and was a joint author of an agreement with Russia concerning the common fight against kidnapping and terrorism. As the second Chechen war began, there were inevitable rumours that Atgeriyev was working with the Russians and had lost the confidence of President Maskhadov. Atgeriyev was eventually lured by two diaspora Chechen businessmen to a meeting in Daghestan with an FSB official (possibly Herman Ugryumov) to discuss a peace proposal ostensibly from Moscow. Atgeriyev was seized and transported to Lefertovo Prison in Moscow.

The temporary commander of the Kizlyar operation, Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov, was one of a number of Chechen leaders who fell leading the Chechen evacuation column through a horrific Russian ambush when the rebels abandoned Grozny in January 2000.

The Death and Resurrection of Salman Raduyev

In March 1996 Raduyev was widely reported as killed in an ambush. Some claimed it was the work of Russian assassins, while others believed Raduyev’s Chechen enemies had eliminated this loose cannon. At the time Raduyev was probably being hunted by both. The claims seemed verified when Raduyev vanished from sight, leaving behind only reports of his death in the Urus-Martan hospital. It had already been reported in the press that President Dudayev had given his son-in-law 1.5 million dollars to distribute amongst his men. After the ambush it was claimed that Raduyev was killed by his former followers after withholding the money from them. A complicated plot was also attributed to the GRU (Russian Military Intelligence), seeking revenge for losses at Pervomaiskoye.

After Raduyev’s death was reported, 101 Estonian parliamentarians signed a letter mourning ‘the atrocious murder of an outstanding freedom fighter’. The letter infuriated the Russian government, which regards the Baltic nations as active collaborators in the Chechen insurrection. Russian field troops active in Chechnya circulate the myth that a squadron of female Estonian snipers on skis has been active in both Chechen wars on the rebel side. Needless to say, none of the ‘White Tights’, as they are known, have ever been killed or captured.

Months after his disappearance Raduyev turned up on Russian television. The man claiming to be Raduyev was unrecognizable. Once Raduyev had had a predatory look, emphasized by a strong nose, a long red beard and gold teeth. The new Raduyev perched dark sunglasses atop an artificial nose. The glasses covered an empty eye socket and damage to the skull caused by the sniper’s bullet. The belief that Raduyev’s skull had been reconstructed using titanium plates earned Raduyev a new nickname among his detractors, “Titanic.” According to one bizarre rumour, Raduyev’s plastic surgeon was the same doctor who treated Michael Jackson.

Where was Raduyev all this time? Russian daily Komsomolskaja pravda claimed to have the answers. After the attack, Raduyev was spirited through Daghestan, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, on into Germany, where he was placed under the care of German Intelligence. Radical surgery was performed at an American hospital near Munich. On recovery, Raduyev was then transferred into the hands of two high-ranking Russian officers. These agents took Raduyev on a circuitous route to Moscow, involving several passport changes. Russian intelligence then re-inserted Raduyev into Chechnya, to continue his work as a provocateur. It was impossible to verify this story, but one thing was clear; the rescue, transfer, medical treatment, concealment, and re-insertion of Raduyev could only have been achieved with resources beyond those of a slightly unhinged Chechen warlord.

On his return Raduyev, just to keep in shape, claimed responsibility for several recent trolley bombings in Moscow, probably the work of local Mafia factions. Raduyev’s big news, however, was that Chechnya’s late president, Dzhokar Dudayev, was still alive. Dudayev, a former Russian air force general, was reported to have been killed on April 21, 1996, when the Russians zeroed in on his satellite phone when he stopped his two-car convoy to make a call. A missile struck Dudayev’s position, killing him instantly. The body was never recovered, though Dudayev’s small entourage may have buried it secretly. The entourage, which included Dudayev’s wife, provided the only witnesses to his death. Raduyev was accustomed to drawing his authority through Dudayev, his father-in-law, and was an interested party in keeping alive rumours of Dudayev’s survival. The late president’s family also claimed Dudayev was alive. Lechi Dudayev, a close ally of Rudayev and later mayor of Grozny, made several such claims (Lechi Dudayev would fall crossing a minefield in the evacuation of Grozny).

There were, in fact, questions about the Dudayev assassination from the beginning. It was unusually precise and efficient for the fumbling Russian army. The necessary technology was not believed to be held by the Russians. Several years ago, Wayne Madsen, a US security analyst, published a little-noticed article in Covert Action Quarterly suggesting that Dudayev’s coordinates were passed along from the US National Security Agency to President Clinton, who was then visiting Moscow in an attempt to shore up Boris Yeltsin’s presidential campaign. [7] Clinton is said to have passed these to Yeltsin, who badly needed a success in his faltering Chechen campaign. Strangely, this story does not seem to have been noticed in the Caucasus region until a major Turkish newspaper revived the story in June 2001. Since then, rumours of Dudayev’s existence have returned, culminating in a suggestion by Akhmed Khadyrov in late August 2001 that Dudayev may still be alive, and ‘having a nice time somewhere’. Khadyrov is no less than Moscow’s appointed governor of the puppet Chechen administration, and a former rebel leader in the first Chechen war. Khadyrov’s remarks must have come as a shock to the Russians. Dudayev’s wife, Alla Dudayeva, has never directly answered the question of Dudayev’s death. When asked to comment on Khadyrov’s remarks, she would only enigmatically quote the Koran; ‘‘Those whom I come for who go in the path of Allah are not dead, they are living’. And he is fighting with the Chechen army, his soul is fighting.’

Following the first Chechen war Raduyev refused to recognize the peace accords, and promised to lead his ‘Army of General Dudayev’ in an ‘eternal war’ against Russia. He issued bold statements, declaring that, ‘If (the Russians) want to fight with me, let them come and we see who wins.’ Political pressure led to the promotion of Raduyev to general, and the rising warlord was publicly decorated for his useless raid on Kizlyar. Sebastien Smith, who knew Raduyev before and after his disappearance, described him in this period as ‘an eerie character’:

The assassination attempt and the surgery have made him even freakier. His face is messy, but not his clothes. Before, he wore ordinary combat gear; now he dresses up in special tailored uniforms with medals, like something from Versace, and travels with a bodyguard of some 40 of the toughest-looking people you’ve seen. He’s too weird for most people. But there are some who always will believe what he says. He’ll always be Raduyev, the man who came back from the dead, the man who says he knows about Dzhokar (Dudayev). [8]

The adulation went to Raduyev’s head, and he was soon needlessly provoking every power structure in the area. In December 1996 Raduyev led a band of armed men to the border with Daghestan and demanded entry. When the 21 Russian and one Daghestani policemen resisted, Raduyev disarmed them and took the group hostage into Chechnya. Engaged in a crucial stage of the peace negotiations, the Chechen government vowed to force Raduyev to release the hostages unconditionally. Raduyev publicly defied Maskhadov for four days, demanding that Russia apologize to him. Eventually Russian envoy Boris Berezovsky arrived to negotiate the release of the hostages.

Raduyev Stands Alone

By 1997 Raduyev began to make a series of threats against Russia, promising a wave of bombings to mark the April 21 anniversary of Dudayev’s death, ‘a day of national revenge’. Though their relations continued to be fractious, the leading Chechen separatists were at the time trying to present a united front in their quest to establish the legitimacy of the fledgling Chechen state. Raduyev’s provocations were even more unwanted in Grozny than in Moscow, and it was not surprising when Raduyev was badly wounded by a bomb planted in his car in early April 1997. Chechen security may have passed information regarding Mr. Raduyev’s intentions to their FSB counterparts. Elements of the Chechen government accused Raduyev of being on the payroll of a Russian ‘Party of War’, politicians and members of the security services opposed to a peace settlement in Chechnya. Raduyev’s intended campaign of revenge appears to have been limited to the blasts in Armavir and Pyatigorsk in April and May of 1997, which Raduyev described as a new phase in the war against Russia.

As with anything connected to Raduyev, the Armivar and Pyatigorsk bombings set off a bizarre series of accusations and counter-accusations. The morning after the bombings, Anatoly Kulikov, then Russian Deputy Prime Minister, called a press conference to announce the arrest of the perpetrators. The alleged terrorists were identified as two Chechen women, Fatima Taymaskanova, then 34, and Ayset Dadasheva, then 24. Confessions and fingerprints had already been obtained, and the terrorists were safely locked up in Lefertovo Prison. The Chechen government responded that one of the two identified women was already dead, and that the photographs of the women shown by Kulikov were of entirely different people. The photos were further alleged to have been lifted from a book by former Chechen president Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev.

At this point, Raduyev announced his responsibility for the bombings, threatening to attack Russia with chemical weapons if the detained women suffered in any way. President Maskhadov, still in crucial negotiations with the Russian government, more pragmatically found the women legal counsel, and declared Raduyev to be ‘a complete idiot’. Yet others within the Russian government saw the hand of foreign intelligence services behind the bombings, allegedly with the purpose of sabotaging Russian-Chechen negotiations.

By June 1997 President Maskhadov decreed the abolition of all private armies in Chechnya, an edict that the President admitted was aimed primarily at Raduyev’s forces. In July 1997 a van filled with explosives blew up in Grozny as Raduyev’s car passed by. Again Raduyev survived, but three others were killed. The Chechen government was attempting at the time to negotiate with Moscow to replace the pipeline carrying Caspian oil to Russian refineries, but Raduyev now promised to destroy the pipeline unless the Russian government conceded Chechen independence. In January of 1998 Raduyev led an anti-Wahhabist demonstration in Grozny, during which he threatened the militarily powerful Islamist faction with violence. Raduyev then seized the opportunity to offend the government as well, demanding that they take an oath against the anti-Sufist Wahhabites, or be declared ‘enemies of Allah and Islam.’ According to Maskhadov, ‘With this commander, we don’t have a political problem, but we have a psychiatric one.’

By now, Raduyev was styling himself the ‘Commander of the Army of Dudayev’, but still smarting from the closure of his television station by the President for broadcasting ‘anti-state propaganda’. On June 21 1998 Raduyev was in the square in front of the Grozny television station with a number of his armed men. They were reportedly gathered for an attempt to seize the state television station. A confrontation developed with Lecha Khultygov, chief of the National Security Service, and his own armed force. There was a firefight in broad daylight, and when the smoke cleared, Khultygov, his bodyguard (a relative of Shamyl Basayev) and Raduyev’s chief-of-staff lay dead in the square. Raduyev was now challenging the young Chechen state while continuing to accumulate enemies bound by the code of blood revenge followed in the highlands. Raduyev was claiming the mantle of Dudayev, but such actions were causing him to lose the support of Dudayev’s clan.

For the moment, though, Maskhadov did not have time to deal with Raduyev. The President had finally become fed up with the constant challenges to his authority from the radical Islamists and the Arab mujahidin who had stayed in Chechnya following the first war. An expulsion order was issued in July 1998 for all foreign Islamists and mujahidin, but Maskhadov had insufficient power to enforce it. The power balance was so delicate at the time that Maskhadov reportedly even considered enlisting Raduyev against the Islamists.

By September 1998 Raduyev was part of a strange alliance with Shamyl Basayev (who had once promised to ‘sort out’ Raduyev personally) and Raduyev’s old comrade from Kizlyar, Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov. The three had found common cause in opposing Maskhadov’s continued negotiations with the Russians, and demanded that Parliament impeach him. Parliament refused, and the three field commanders had their demands referred to the Shari’a court. Maskhadov struck back, singling out Raduyev for arrest. The Supreme Shari’a Court sentenced Raduyev to four years imprisonment for ‘insubordination’, but after one failed arrest attempt, Raduyev was left alone by the Chechen security forces. Maskhadov, well aware of the fragility of the Chechen state, habitually preferred compromise to confrontation with his unruly field commanders, and offered a conciliatory gesture to Raduyev. The four-year sentence would be dropped if a medical examination determined that the warlord was ill. Raduyev’s response was to fortify his Grozny compound and surround it with armed guards.

Raduyev in Chains

In March 1999 Raduyev claimed responsibility for the brazen kidnapping of Russian General Gennady Shpigun from a helicopter at Grozny airport. The warlord’s almost compulsive confessions were no longer bought by everyone. Raduyev’s ambitious habit of claiming responsibility for all types of outrages in order to cultivate a fearsome reputation led to a joke in Grozny that Raduyev would claim responsibility for Kennedy’s assassination, had he been alive then. Other suspects (among many) in the Shpigun abduction included Baudi Bukayev, notorious kidnappers the Akhmadov brothers, the ruthless Islamist (and possible Russian agent) Arbi Barayev, or Abdul-Malek Mezhidov, a follower of warlord Ruslan Gelayev. Where else in the world but Chechnya could one find literally dozens of individuals capable of orchestrating such an outrageous act – and from a population of less than a million people? (Shpigun was later found dead from exposure and other causes, having apparently escaped from his captors but failing in his attempt to reach Russian lines).

The Kennedy joke was not far off the mark, as it turned out. Raduyev bizarrely claimed responsibility for the 1998 assassination attempt on President Eduard Schevardnadze of Georgia. The claim puzzled everyone, not least the Georgians, who saw Russian hands behind the attack. Later, Raduyev would deny his responsibility, claiming his remarks were ‘taken out of context.’ After his arrest, Raduyev again confessed to the assassination attempt.

Raduyev began the latest war in a belligerent mood, announcing at huge rallies that he would lead his personal army against the Russians. Large-scale operations by the ‘Army of Dudayev’ did not materialize, and by February 2000 the Russian General Staff were again reporting the death of Raduyev. The story this time was that Raduyev had attempted to sell the whereabouts of warlord Ibn al-Khattab to the Russians for a million dollars. Al-Khattab was the Saudi-born leader of the foreign mujahidin, a veteran of several Islamic insurgencies, survivor of numerous assassination attempts, and a very nasty character to antagonize (Khattab was killed in March 2002, reputedly the victim of a letter laced with poison by the FSB). The Khattab-Raduyev story was, however, yet another Russian invention.

Even the basic details of Raduyev’s arrest are in doubt. One version held that Raduyev was arrested while attempting to betray Shamyl Basayev for a million dollars, no doubt a variation of the al-Khattab story. Kommersant Daily of Moscow reported that Raduyev had himself been betrayed by Basayev. According to other sources, Raduyev had received shrapnel wounds to the head, and was traveling out of Chechnya in disguise with two associates to seek medical treatment. When he reached the Chechen-Ingushetian border, Raduyev was recognized by two Chechen arms-dealers who informed the Russians for the price on his head. Unarmed, Raduyev was arrested without a struggle, but FSB reports soon began to claim that a complex FSB operation had found Raduyev and arrested him under the noses of over one hundred heavily armed bodyguards (all apparently happily camped behind Russian lines). After his arrest, Raduyev confessed so quickly that investigators began to doubt they had the right man. Was this ill and damaged creature truly the demon Raduyev, one of Great Russia’s most dangerous enemies? Medical examination revealed that the individual in Moscow’s Lefortovo Prison had no titanium plates in his head, as Raduyev was so often said to have. The FSB did report, reassuringly, that Raduyev was ‘physically healthy, his hands do not tremble, and no signs of narcotic dependence were discovered.’ Chechen rebels are typically depicted by the Russians as narcotics addicts and/or dealers. Sometimes it is claimed that dead Chechen fighters are found with large packets of heroin in their pockets, though why anyone would stuff his pockets with heroin before going into action is never quite explained.

Andrei Babitsky, a noted journalist with American-sponsored Radio Liberty, provided a further version of Raduyev’s arrest. Babitsky maintains that Raduyev’s arrest was designed by Putin to weaken oligarch Boris Berezovsky, once a leading supporter of Putin. Berezovsky, who has since fled Russia, was accused of funding Raduyev’s operations. Berezovsky was already widely rumoured in Moscow to have financed Basayev and al-Khattab’s summer 1999 invasion of west Daghestan that sparked the current war.

Raduyev found the odds stacked against him once he reached the courtroom. Russian authorities decreed the trial would take place in Daghestan, the most hostile possible site in the world’s largest nation for Raduyev. Hundreds of Daghestanis were believed to have taken blood-oaths of revenge on Raduyev in retaliation for the deaths of Daghestanis in the raid on Kizlyar. The prosecution was led by the Prosecutor General of Russia himself, Vladimir Ustinov. Such a remarkable step had not been taken since the 1960s, when the Prosecutor General of the USSR led the case against US spy plane pilot Gary Powers. Court-room duties are not part of the job description of the normally busy Prosecutor General, and serious questions were raised as to how Ustinov intended to try a huge case far from Moscow and fulfill his other duties. The investigation produced over 130 volumes of evidence, and more than 3,000 witnesses were identified. Cross-examinations alone were projected to take at least a year, but the trial was instead wrapped up in a relatively swift five weeks. Part of Ustinov’s inspiration for taking the case himself may have been the acquittal of two Chechen suspects accused of a second bombing of the Pyatigorsk rail station in October 2000. Russian prosecutors could not afford such a failure in a case of Raduyev’s profile. Ustinov began by taking an aggressive approach, with his office spreading the word that Ustinov might seek ‘exceptional measures of punishment’ for Raduyev. This referred to a possible breach of the moratorium on capital punishment declared by Russia as a condition for membership in the Council of Europe. Ustinov seemed to have forgotten the strident objections of Russian legal authorities to executions carried out by Shari’a courts in Chechnya after the conclusion of the first war. At the time they were condemned as violations of the moratorium, endangering Russia’s international position.

Raduyev’s appointed lawyer, Pavel Nechipurenko, said before the trial that the warlord’s defence would be that he was involved in a war situation, and simply followed orders like any other soldier. Nechipurenko also asserted that Raduyev is ‘an absolutely normal person,’ seemingly in accordance with the view of Russian prosecutors that there was no need for a defence based on insanity, or diminished capabilities. Nechipurenko was eventually replaced by a less cooperative lawyer, Salman Arsanukayev.

Ustinov used the trial to paint a vivid picture of life in the warlords’ Chechnya: ‘Bandit formations robbed passing trains. The economy was ruined, there were robberies, arms deals, money schemes, and slave labour.’ Initially shorn of his beard and hair when arrested, Raduyev looked more familiar during the trial with his characteristic long beard and mirrored aviator sunglasses. Raduyev and his fellow defendants observed the trial from within a steel cage. The warlord visibly infuriated the Prosecutor-General by maintaining that Federal security forces were responsible for the huge number of hostages killed at Pervomaiskoye. Raduyev’s lawyer was more conciliatory, attempting to pin the blame for the deaths on the late Colonel Israpilov. Raduyev disclaimed personal responsibility for the raid, claiming that he and Israpilov were personally entrusted with the mission by President Dudayev. With Israpilov and Dudayev both dead, there was no way to confirm Raduyev’s defence, though Ustinov still had trouble proving the raid was Raduyev’s idea. The two men responsible for the attack on the rebels at Pervomaiskoye, former Interior Minister Anatoly Kulikov, and former FSB chief Mikhail Barsukov both refused to testify against Raduyev. Attempts were made by the prosecution to implicate current President Maskhadov in the operation, but the allegations were hotly refuted by Raduyev and Atgeriyev. Though extremely frail at the time of his arrest, Raduyev mounted a spirited if unendearing defence, frequently interjecting with sarcastic remarks or political statements.

Raduyev was simultaneously tried for the 1997 Pyatigorsk railway station bombing. The young women initially charged with the crime testified that they had been promised rewards such as cash and apartments for their role, but were unable to implicate Raduyev directly. News agency Chechenpress claimed to have letters from the two women describing confessions made under torture and suggested that the women had been promised early release for testifying against Raduyev. At one point in their confessions, the women had asserted that they were both mistresses to Raduyev. The low point in the trial undoubtedly came when the prosecution invited Natalya Rybasova, a survivor of the blast, to testify about her experience. Rybasova had lost a 3 year old grand-daughter in the explosion, and angrily called Raduyev ‘scum’. Raduyev responded with curses, and it was some time before the judge was able to restore order.

The final verdict was 700 pages and took several hours to read. Raduyev was sentenced to life imprisonment, Atgeriyev to fifteen years, Alkhazurov to eight years, and Gaysumov to five years. Lida Raduyeva, the warlord’s wife, mounted an aggressive defence of her husband in an interview with Azerbaijani newspaper, Ulus: ‘Many (of Raduyev’s friends) betrayed him. In essence it was impoverished people who supported him. Salman does not love to share his agitations. He suffered from the treachery of friends and indicated that it was necessary to suffer. He said, ‘God will judge’. Those people in whom he trusted… were all killed. Salman, even knowing (the identities of) those responsible for the attempts on his life, did not hurry to blame them.’

Atgeriyev had barely started his fifteen year sentence at Penitentiary Colony no.2 (Sverdlovsk Region) when he was declared dead of natural causes on August 18, 2002. Those who knew Atgeriyev best testified that he was in good health when he entered the Russian prison system; the Justice Ministry claimed his ‘natural death’ was the result of ‘leucosis (and) spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage’. The statement asserted that ‘no signs of violent death have been detected’. In an interview to Associated Press, Chechen Presidential envoy Akhmed Zakayev said he believed that Atgeriyev was working with the Russians, but had eventually been murdered by them. ‘This should be a lesson for anyone who is putting their hopes on Russian justice and Russian clemency.’ The following day Zakayev’s name appeared as the author of an official Chechen government statement condemning Atgeriyev’s ‘murder’. When asked for a reaction to Atgeriyev’s death, General Gennady Troshev (recently relieved commander of the North Caucasian Military District) simply stated; ‘A wolf does not live in captivity’ (an apt allegory). Some Chechens expressed disbelief with the death report, believing instead that Atgeriyev had been secretly released to begin a new life after cooperating with the Russians.

So Raduyev, the enigma with two faces, began another life behind Russian bars. Even in such seclusion, however, there were secrets of the Chechen rebellion that some in Moscow did not want discussed even in whispers. The prison deaths of Atgeriyev and former Chairman of the ChRI Parliament Ruslan Alikhadjiev seemed to set a bad precedent for Raduyev’s survival. Raduyev was, after all, not a well man, and a quiet death in prison would please many on both sides of the conflict. The news that Raduyev intended to write a book about his experiences did nothing to increase his popularity. Some, however, continued to deny that the man tried in Daghestan was actually Raduyev; Doku Zavgayev, former Communist Party boss of Chechnya, still maintained that Raduyev died in the Urus Martan hospital, and invited anyone to simply ask the doctors there. Just before sentencing, Raduyev had his own thoughts about his fate: ‘I couldn’t care less if I get a life sentence. I have died three times already. I can spend my life in prison. I have no regrets.’

Raduyev was sent to Solikamsk Detention Centre no.14 in the Ural Mountains, about 1200 kilometers east of Moscow. At first he was kept in solitary confinement, but was later roomed with Alexander Grishayev, a serial killer. Raduyev’s lawyer, Arsanukayev, submitted an appeal to the European Court on Human Rights in Strasbourg, and was preparing a further appeal to the Russian Supreme Court, challenging the evidence presented in the Pyatigorsk bombing case, for which Raduyev had received the life sentence. The advocate also insisted that his client should have been treated as a prisoner-of-war. As such, Raduyev would not be subject to criminal prosecution. Little was heard from the imprisoned warlord until the Moscow hostage-taking crisis of late October 2002 returned Raduyev’s name to the news.

The Kremlin seized on the opportunity provided by the shocking outcome of the hostage-taking to demand Denmark immediately cancel a forthcoming Congress of Chechens in Copenhagen, and to extradite Maskhadov’s personal envoy, Akhmed Zakayev, to Russia as an international terrorist. Russian Justice Minister Yuri Chaika tried to reassure the Danes, pointing out that Russia had placed a moratorium on the death penalty and pointed out that even such a dangerous terrorist as Salman Raduyev had only received a life sentence. On November 26 2002 Russia’s General Prosecutor announced that Raduyev had given evidence regarding Zakayev’s ‘terrorist activities’, namely his participation in the 1999 Islamist incursion into Daghestan (a campaign in which Raduyev had no part). According to Russian records, Raduyev’s health problems started soon after his testimony. The Raduyev revelations appeared to be part of a typically sloppy and unconvincing campaign by Russian authorities to demonstrate Zakayev was a terrorist threat. Kremlin attempts to portray Zakayev as a priest-killer were foiled when the Orthodox priest allegedly killed by Zakayev surfaced in Russia with a plea that he and the church be left out of Moscow’s international machinations.

On December 14 Russian prison authorities announced that Raduyev had died as the result of a gastrointestinal hemorrhage, ‘exacerbated as a result of fasting for Ramadan.’ Almost immediately there were conflicting reports as to whether Raduyev had died at the Solikamsk hospital (which services the surrounding labour camps), or in his prison cell as the result of a beating from guards. The Maskhadov government’s official Chechenpress news agency declared Raduyev’s death ‘a murder,’ resulting from his unwillingness to cooperate with Russian officials in creating a case against Zakayev. Several Russian newspapers reported that it was the murderer Grishayev who notified prison guards that Raduyev had stopped breathing following a beating for refusing an order during a search of his cell.

On December 16 Amnesty International demanded an investigation into Raduyev’s death. Opportunities for an independent inquiry were quashed when Raduyev’s body was buried in the convicts’ section of the Solikamsk cemetery on December 17. Authorities declared that none of Raduyev’s relatives had claimed the corpse within the allotted three days, and that there was no legal reason in any case to release the body in view of recent changes in Russian law that forbade releasing the bodies of ‘terrorists’ to their families. There were also assurances that no investigation was needed, as the warlord had died of ‘natural causes’. The following day an appeal by Raduyev’s family for a reburial in his homeland was refused on sanitary and legal grounds.

According to the Deputy Minister of Justice, an autopsy had revealed that far from having been beaten, ‘nobody even touched him with a finger’… His death was the consequence of a large number of diseases, from which he suffered since childhood. Furthermore he was seven times injured and contused, and in 1996 and 1999 his health status worsened’. [9] Though the imprisoned Raduyev had once railed that he would live 350 years and survive all his tormenters, he, like Atgeriyev, did not survive the first year of his sentence.

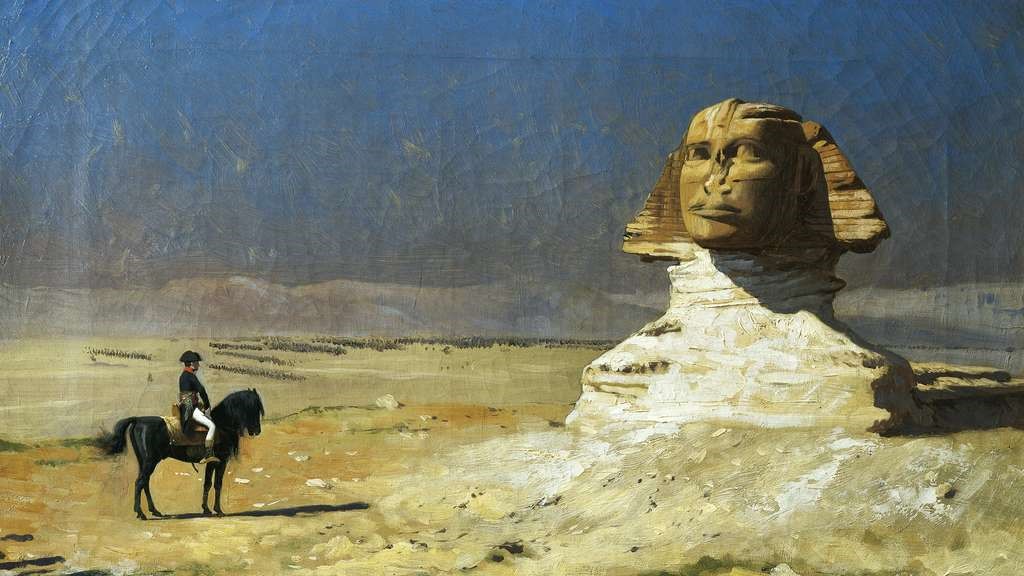

Salman Raduyev on Trial

Salman Raduyev on Trial

The manner of Raduyev’s death remains as mysterious as the conduct of his life. Though the warlord achieved international fame in his lifetime, he is unlikely to be placed among the heroes of the Chechen resistance by any other than his diminished number of followers. In light of the suspicions regarding Atgeriyev’s alleged ‘false death’ and the quick and unobserved burial of Raduyev’s body in a remote Urals grave-site, there will inevitably be those who will suspect Raduyev has once again cheated death, and has claimed his reward as a Russian provocateur. Like the Cheshire cat, Raduyev has faded from the scene, leaving only his mocking grin.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

AIS Update, January 2017: What happened to Salman Raduyev’s contemporaries?

Shamyl Basayev – Chechnya’s most prominent field commander was killed in January 2006 by a powerful explosion during an arms shipment in Ingushetia. The blast scattered Basayev’s remains as far as a mile away. It remains uncertain whether his death was accidental or the result of a FSB assassination operation. A Chechen involved in the assassination of several Chechen separatists in Turkey was later suspected of having prepared the fatal charge on behalf of the FSB.

Boris Berezovsky – Forced to take exile in London, Berezovsky survived several assassination plots before apparently hanging himself at home in 2013. The coroner delivered an “open verdict” on his death. A Russian “espionage expert” claimed in 2016 that Berezovsky had been assassinated by British secret services over his possession of allegedly embarrassing photos of Prince Philip.

Ibn al-Khattab (a.k.a. Thamir Saleh Abdullah) – The Saudi jihadist was killed by a poisoned letter delivered by a FSB operative in March 2002.

Aslan Maskhadov – The Chechen president was killed by Russian Special Forces in a raid on a bunker in Tolstoy-Yurt in March 2005 after declaring a unilateral ceasefire in the Second Chechen War. His body was placed in an unmarked grave in a secret location.

Lida Raduyeva – Raduyev’s wife moved to Istanbul with Raduyev’s two young sons, Cevher and Selimhan.

Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev – The former Chechen President was assassinated by FSB agents in Doha, Qatar in 2004. Though the agents succeeded in killing Yandarbiyev, sloppy field-work led to their apprehension, deportation and subsequent disappearance following an international scandal.

Akhmed Zakayev – Zakayev’s extradition was prevented by a UK court ruling, but he was later warned he was on hit-lists created by the FSB and Ramzan Kadyrov, the pro-Moscow ruler of Chechnya. He was later sentenced to death in absentia by the rebel Caucasus Emirate in 2009 for failing to advocate Shari’a. He continues to reside in London but his influence on Chechen affairs is much diminished.

Notes

- Andrew McGregor: ‘‘Flying to the Moon on a Balloon’: Islamist coups and conspiracies in the Northwest Caucasus,’ Central Asia – Caucasus Analyst (Central Asia Caucasus Institute – Johns Hopkins University), November 20, 2002, www.cacianalyst.org/2002-11-20/20021120_NORTHWEST_CAUCASUS_ISLAMISTS.htm

- The Ingush and Chechens are closely related, speaking similar dialects of the same language. Collectively they are known as the Vaynakh. They were united in the same Soviet republic until 1991, when the more-militant Chechens decided to pursue complete independence from Russia. The break was nevertheless amicable; Ingushetia is the main destination for Chechen refugees and small numbers of Ingush volunteers can be found within the ranks of the Chechen mujahidin.

- Aleksander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, v.III, Collins, London, 1978, p.410-18.

- The standard history of the Caucasian deportations can be found in Robert Conquest: The Nation Killers: The Soviet deportation of nationalities, MacMillan, London 1970. See also William Flemming: ‘The Deportation of the Chechen and Ingush Peoples: A critical examination,’ In: Ben Fowkes (ed), Russia and Chechnia: The Permanent Crisis: Essays on Russo-Chechen Relations, MacMillan, London, 1998, p.65-86. Two important articles in English have been produced by Vera Tolz that use information available since the opening of the Soviet archives; ‘New information about the deportation of ethnic groups in the USSR during World War 2’, In: J and C Garrand (eds), World War 2 and the Soviet People, MacMillan, London, 1993, p.161-80, and ‘New information about the deportation of ethnic groups under Stalin’, Report on the USSR, Apr.16, 1991, p.15-20

- Two Sufi orders are common in Chechnya, the Naqshbandi and the Qadiri. The Islamization of Chechnya was a slow process, and Islam did not take effective hold in the area until the eighteenth century. The militant Naqshbandis were the dominant order until the later years of Shaykh Shamyl’s rebellion (1825-59), when Kunta Hajji introduced the more reflective and unwarlike Qadiri order despite Shamyl’s opposition. Within several years, however, the Qadiri order underwent a transformation after repeated Russian abuses in Chechnya, replacing the Naqshbandis as the most militant of the forces fighting for Chechen independence.

- Carlotta Gall and Thomas de Waal, Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus, New York University Press, New York, 1998, p.292.

- Wayne Madsen, ‘Did NSA help target Dudayev?’, Covert Action Quarterly no.61, 1997, pp.47-9.

- Sebastien Smith: Allah’s Mountains: Politics and war in the Russian Caucasus, London, 1998, p.236.

- Russian Deputy Minister of Justice Yuri Kalinin, Interview for ITAR-TASS, reported in http://www.vesti.ru/news.html?id=21821&tid-10087

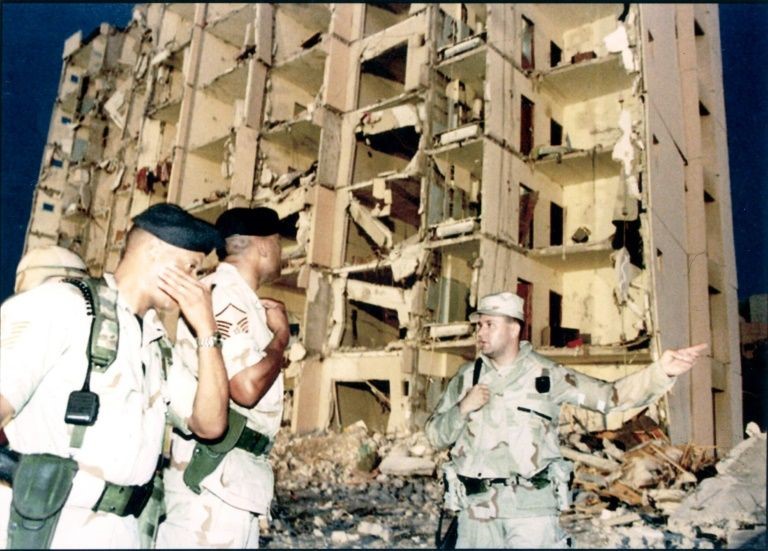

Amir Abu al-Walid (al-Jazeera)

Amir Abu al-Walid (al-Jazeera) Abu al-Walid with Chechen Field Commander Shamyl Basayev

Abu al-Walid with Chechen Field Commander Shamyl Basayev