Strategic Datalink no. 80, September 1999

Strategic Datalink no. 80, September 1999

Andrew McGregor, Canadian Institute of International Affairs

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a low-level Islamist rebellion has simmered along Russia’s frontier with the new Central Asian states. In August of 1999, this rebellion crossed into Russia proper as Islamist fighters seized territory in the Russian republic of Dagestan. The explosive violence of the insurrection has dealt another embarrassing blow to Russian security forces and largely eliminated any hope of a Russian-Chechen reconciliation as Russian bombers struck deep into Chechnya in attempts to destroy rebel training bases.

Most of the current analysis of the conflict has depicted the rebellion in terms of a Chechen-inspired Islamic/nationalist revolt against the Russian state, much like the 1994-96 conflict in neighboring Chechnya. The presence of leading Chechen guerrilla commanders such as Shamyl Basayev lends weight to the notion that the fighting in Dagestan is an extension of the earlier conflict into a new arena. Lost in this line of reasoning are the severe divisions the fighting has revealed in the Chechen leadership and the importance of ultra-conservative Islamic “Wahhabism” in creating the direction of the revolt. The Wahhabi campaign in Dagestan is concerned just as much with conquering the Dagestanis as with expelling the Russians.

Most of the current analysis of the conflict has depicted the rebellion in terms of a Chechen-inspired Islamic/nationalist revolt against the Russian state, much like the 1994-96 conflict in neighboring Chechnya. The presence of leading Chechen guerrilla commanders such as Shamyl Basayev lends weight to the notion that the fighting in Dagestan is an extension of the earlier conflict into a new arena. Lost in this line of reasoning are the severe divisions the fighting has revealed in the Chechen leadership and the importance of ultra-conservative Islamic “Wahhabism” in creating the direction of the revolt. The Wahhabi campaign in Dagestan is concerned just as much with conquering the Dagestanis as with expelling the Russians.

Rather than constituting a nationalist struggle, as in Chechnya, the campaign in Dagestan is the military expression of a two-and-a-half century old Islamic movement that has been reinvigorated as the ideology of the foreign volunteers who fought communism in Afghanistan. These mujahidin have gone on to form the core of Islamic resistance movements throughout Asia and the Middle East.

Traditional Tower in the Dagestan Mountains (Hotel-all.ru)

Traditional Tower in the Dagestan Mountains (Hotel-all.ru)

Russia, in seeking Western support for its 1994-96 Chechen war, overemphasized the importance of Islam as a source of the conflict, describing the Chechen nationalists as “Muslim fundamentalists,” which clearly, they were not. Even General Dudayev, the late Chechen president, warned in 1991 of the dangers of Islamic fundamentalism if the nation did not follow a politically secular path. While nationalism drove the Chechen rebellion, it was the discipline provided by the introduction of the Shari’a (Islamic law) that helped keep the guerrillas in the front lines through the war’s darkest days. The appeal of a more conservative form of Islam grew among some commanders such as Shamyl Basayev, one of the war’s Chechen heroes. For many others though, Shari’a came into conflict with the still important pre-Islamic Chechen code of tradition know as the adat.

Wahhabi Origins

The Wahhabist movement derives its name from the puritan reforms introduced to Arabian Islam in the 18th century by ‘Abd al-Wahhab, a formidable religious reformer who took inspiration from the teachings of the Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328). He rejected religious innovation, the survival of pre-Islamic traditions, pilgrimages to shrines, saint-worship and the cult of intercession; in short, the core of popular Islam as it is practised in the Sufi-influenced North Caucasus. The modern importance of Wahhabism is derived through the Wahhabi alliance with the founder of Saudi Arabia, ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn Sa’ud, whereby it became the officially recognized form of Islam in that nation.

Though the puritanism of modern Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia has been tempered by political necessity in the post-war decades, the Wahhabism espoused by missionaries and guerrillas in Central Asia and the Caucasus bears none of the restraints found in the Saudi court. Wahhabis often refer to a struggle against “Sufis, saint-worshippers and grave-worshippers,” whom they refuse to acknowledge as true Muslims, and therefore not subject to the prohibition against fighting fellow Muslims. Long seen as a militant expression of Arab superiority over backsliding non-Arab Islamic cultures, the recent growth of Wahhabism in the Caucasus and through the Turkic cultures of post-Soviet Central Asia and China represents an important step in the growth of the movement.

The core belief of Wahhabism is tawhid (literally the “unity” of God), an unflinching commitment to monotheism. The movement rejects the term “Wahhabi” (which implies worship of the man rather than adherence to his ideals), preferring the name muwahhidun, or Unitarians.

The Russian government has warned of the “dangerous expansion of Wahhabism” in Central Asia, and even signed a pact with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in May of this year to combat the movement. The pact is similar to one China signed with the Central Asian states in 1998 in an effort to dampen Islamic militancy in its western province of Xinjiang. [1] In late August, as the Russians battled Wahhabis in Dagestan, President Yeltsin attended a summit of the “Shanghai Five” (named for a previous summit) in Kyrgyzstan. While the summit of leaders from Russia, China, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan continued, troops from the host country of Kyrgyzstan were battling Islamist guerrillas who had seized several villages in the east of the country. It has been suggested that the gunmen were also responsible for February’s assassination attempt on Uzbekistan’s president.

Islam in Conflict

While quick to designate fellow Muslims as guilty of shirk (polytheism) because of even slight variations from the spirit of eighth century Islam, the Wahhabis have always reserved a special antagonism towards followers of Shi’a Islam (as practiced in Iran, southern Iraq, eastern Saudi Arabia and elsewhere) and members of the mystical Sufi brotherhoods that often incorporate pre-Islamic elements in their rituals and customs. Sufism, or “popular Islam,” can be found everywhere from Bosnia to Indonesia, but it is particularly well grounded in the North Caucasus, making it seemingly infertile ground for Wahhabi expansionism. The lengthy list of prohibitions on personal and social activities demanded by the Wahhabists are also certain to dim their appeal to most Muslims of the North Caucasus. Dagestanis, who converted to Islam centuries before their Chechen neighbors, are on principle unlikely to accept Chechen leadership in any Islamic movement.

In the North Caucasus, Sufi Islam has long been seen to be the staunchest defender of national independence, with the tombs of great Sufi leaders martyred in the struggle against Russian imperialism being among the most revered and visited sites in the region. Sufism survived the Soviet period because the communist rulers of the Caucasus realized, after a long period of persecution, that the only effective way to combat Sufism was to re-invigorate more orthodox forms of Islam. This option was a non-starter for the atheist Soviets in Moscow.

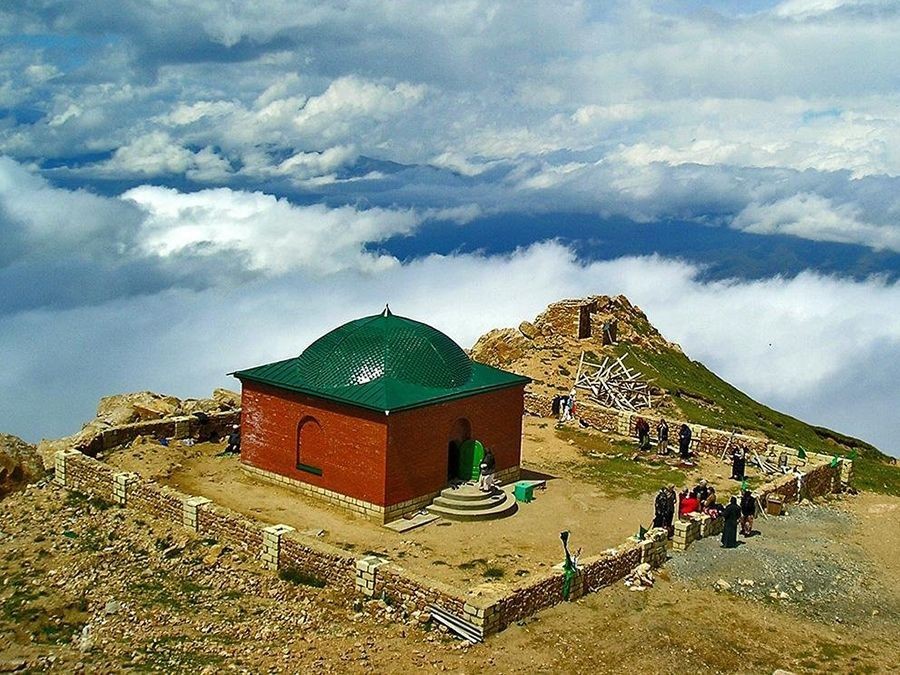

The Mosque of Sulayman on Mount Shalbuz-Dagh (Hotel-all.ru)

The Mosque of Sulayman on Mount Shalbuz-Dagh (Hotel-all.ru)

At Mount Shalbuz-Dagh in southern Dagestan (a place where the Prophet Muhammad was said to have ascended to the summit on horseback, but is more likely to be a holy site of pre-Islamic origin), seven ascents of the mountain were considered locally to be the equivalent of the pilgrimage to Mecca. Traditions such as these represent the grossest heresy to the Wahhabis. Unlike some other areas where Sufi orders showed submissiveness to Soviet rule, the brotherhoods of Dagestan proved capable of mobilizing and leading resistance to those who would challenge local Islamic practice. The current Wahhabi revolt is not only a challenge to Russian rule, but is the first major challenge to Sufi leadership of independence movements in the North Caucasus since the eighteenth century. To the Wahhabis, the current state of religious expression in the Caucasus is akin to that found by al-Wahhab in 18th century Arabia; full of deviation and pre-Islamic custom, ripe for the most severe Orthodox reformation.

Wahhabism in the North Caucasus

The Wahhabists saw in the Chechen war an opportunity to expand their presence in the Caucasus, providing fighters and refugee relief while missionaries spread the word of Islamic reform and revival. Following the war, the continued Wahhabi presence produced violent religious tensions in Chechnya. In 1997, armed clashes occurred in Dagestani Kari-Makhi between hundreds of Wahhabist converts and more traditional supporters of Sufism. The Wahhabists gained the upper hand, policing the area themselves according to the Shari’a. An attempt by Russian prime minister Sergei Stepashin last year to buy off the Wahhabites with expensive Western medical equipment was a failure, with the Wahhabites accepting the equipment but refusing the presence of Russian police.

After declaring victory against the rebels in late August, the Russian security forces turned their attention to the Wahhabist enclave around Kari-Makhi and Chaban-Makhi south-west of the capital of Makhachkala. Instead of an easy victory over the villagers, the Russians only succeeded in opening a second front as the Dagestani Wahhabis fought back ferociously. Their bombing of a military apartment complex in the nearby town of Buinaksk sent shock waves to the highest levels of the Russian government. At the same time, Wahhabi guerrillas once again poured over the border from Chechnya into the Novolakskoye district in western Dagestan. Russian bombing raids on Chechen targets and the consequent civilian losses will only ensure a steady supply of Chechen volunteers to take up the fight against the hated Russians, thereby playing right into the hands of the rebel commanders.

The campaign mounted by an international group of Wahhabist fighters in Dagestan has gathered little public support, other than in the small Wahhabite communities, and, to a lesser extent, in the western border area of Dagestan, where 60,000 ethnic Chechens live. Isolated by language and geography from most other Dagestanis, these communities have little influence in the republic, which has a complicated power-sharing agreement among its 34 ethnic nationalities. [2] Moderate Muslim leaders have strongly opposed Wahhabism, and called for the arrest of the council of Muslim leaders who gathered in Botlikh to declare an independent Islamic State of Dagestan. The Wahhabis appear determine, however, to impose their will on the rest of the republic; according to one Wahhabi leader, “If the people of Dagestan don’t like to live in accordance with the law of Allah, we will take corresponding steps…”. [3] The rebels have even gone so far as to form a tribunal to judge the members of what they referred to as the “occupation government” of Dagestan. Despite three decades of resistance to the Russians offered by the legendary 19th century Dagestani Imam Shamyl, the current Dagestani government has sided solidly with Russia in the current conflict, even providing local militias with arms to combat the Wahhabi threat. This strategy has been questioned within Russia, which still has a standing army of 1.2 million men and several hundred thousand Interior Ministry troops.

Igor Ivanov, the Russian foreign minister, has denounced the presence of “foreign mercenaries” in Dagestan and sternly warned the Organization of the Islamic Conference (an umbrella group of Islamic governments) of the consequences of interference in Russian domestic affairs. Moscow has further accused Saudi Arabia and Kuwait of funding the Wahhabites, and even claimed a connection between the Dagestani rebels and the notorious Osama bin Laden. In September, Russian interior minister Vladimir Rushailo informed FBI director Louis Freeh that Bin Laden was directing the Wahhabi operations in Dagestan, but so far the Russians have failed to provide any evidence of their allegations of foreign support.

Leaders of the Rebellion

The Wahhabi fighters operating in the Caucasus are led by the high-profile Chechen commander Shamyl Basayev, and a shadowy but highly experienced Jordanian known only by his nom de guerre, Khattab. Beside the contribution of his formidable military talents, Basayev assumed the early role of public leadership of the rebellion, issuing statements and posing for photographers. Basayev is, however, a fairly recent addition to the troubles in the Dagestan frontier where the committed Wahabbist Khattab has been operating for several years.

Emir Khattab and Shamyl Basayev

Emir Khattab and Shamyl Basayev

Basayev’s pan-Islamist inclinations were shown as early as 1991, when he joined the armed force of the Confederation of the People of the Caucasus, eventually commanding a force of foreign Islamic volunteers in the Abkhazian separatist struggle against Georgia in 1992. During this conflict Basayev received covert military training from Russian security forces. In 1994, after further training in Afghanistan, Basayev was ready to emerge as a daring rebel commander in the Chechen war of independence, leading an audacious commando raid on the Russian town of Budenovsk as well as the stunning two-day re-conquest of the Chechen capital of Grozny against an entrenched Russian force at least ten times the size of his lightly armed group of fighters.

Basayev appears not to have found a niche in the post-war political structure of Chechnya. Having lost the presidential election to the more pragmatic Alsan Maskhadov (Chechen chief-of-staff in the war), Basayev recently served six months as prime minister before resigning to dedicate himself to the “liberation” of Dagestan. Tensions are well known between the conservative Maskhadov and the militant Basayev, who views the Chechen war as only the first step in the expulsion of Russia from the entire North Caucasus. Basayev and his allies are committed to restoring the Shari’a-based North Caucasus Emirate (1919-20). Led by Uzun Hadji, a 90-year-old Sufi sheikh, the Emirate united Dagestan, Chechnya, North Ossetia, Ingushetia and Kabardino-Balkaria. The Bolsheviks admired Uzun Hadji for his iron will; as an old man he had survived 15 years imprisonment in Siberia and once promised to “weave a rope to hang students, engineers, intellectuals and more generally all those who write from left to right.” [4] The Wahhabis envision a theocratic “Islamic Confederation of the North Caucasus” covering the same area as the former Emirate. Some Russians fear that the Islamist Caucasians also have designs on areas within Russia proper, including parts of Stavropol and Krasnodar krais, and Rostov Oblast. [5]

Despite the trouble the Dagestan adventure has caused Maskhadov in repairing Chechen-Russian relations, ties of comradeship seem apparent in Maskhadov’s unwillingness to cooperate with the Russians in suppressing the Wahhabi bases and supply lines in Chechnya. The extent of Maskhadov’s patience with the fiery Basayev is, however, unknown. Many observers have regarded a civil war within Chechnya as inevitable, but so far the deep-seated Chechen aversion to killing other Chechens seems to have prevented open conflict.

In Russia, Basayev is publicly despised as a terrorist, and privately feared as a brilliant guerrilla leader and a major threat to Russian dominance of the Caucasus. His reputation is so formidable that once, after musing to shocked reporters that if food ran out for his men they could always eat dead Russian soldiers, he felt compelled by their expressions to add that he was only joking.

Shamyl Basayev and ChRI President Aslan Maskadov

Shamyl Basayev and ChRI President Aslan Maskadov

In late August, Maskhadov sacked security advisor Mavladi Udugov and security chief Ibrahim Khultigov for their participation in the attack on Dagestan. Udugov was the energetic and often flamboyant spokesman for the Chechen forces in the 1994-96 war against the Russians, but reinvented himself for the subsequent presidential elections as a dour, black-suited Islamist. Well respected by the Russians for his control of information and handling of international media, Udugov’s support is a major contribution to the rebel effort. While Udugov presents confident rebel commanders in press conferences and television interviews, Russian public relations remain as confused and unbelievable as ever. After mistakenly bombing the Republic of Georgia, Russian spokesmen claimed that unnamed individuals had carried unexploded Russian bombs from Chechnya to Georgia before strewing them on the ground in order to cause embarrassment to the Russians. Only after this rather preposterous refused to float did the Russians finally admit to a mistake.

In his mid-thirties, like Basayev, Emir Khattab arrived in Chechnya in early 1995 leading a mujahidin battle group composed of Saudi Arabians and North African Arabs. A veteran of the Afghan war, Khattab keeps his origins secret but is believed to be a Jordanian ethic Chechen, a member of the extensive North Caucasus exile community in Jordan. By other accounts, Khattab is held to be a Saudi Arabian, marked by a heavy regional accent in his Arabic. Wounded three times in the Chechen war and denounced by the Russian government as a foreign mercenary, Khattab remained in Chechnya after the war, marrying a Dagestani woman. Known locally as “the Black Arab,” Khattab and his men have frequently been accused of forming one of the leading gangs in Chechnya’s lucrative post-war kidnapping business.

Emir Khattab with Rocket Launcher

Emir Khattab with Rocket Launcher

Khattab gained immense notoriety in the Chechen war with his destruction of a Russian column at Yarysh-Mardy in March 1996, the humiliation of which is thought to have led the Russians to assassinate Chechen president Dudayev in reprisal. His contributions to Chechen independence have made Khattab impossible to remove from Chechnya, though the Maskhadov government is well aware that the Wahhabis regard Chechnya’s dominant form of Sufi Islam as heresy. Customarily accused by the Russians of any outrage in the region, including the murder of six Red Cross workers in the village of Novye Atagi in 1996, Khattab has responded: “Whenever anything happens, the Kremlin immediately accuses me, without a shred of evidence.” [6]

Since the end of the Chechen war, Khattab has run a number of guerrilla training bases in eastern Chechnya, though these were mostly destroyed by Russian air raids in late August 1999. It was from these bases that Khattab launched an attack on the Russian armour base at Buinaksk in December of 1997. Khattab claims that his force of 115 “foreign mujahidin” surprised the garrison and destroyed 300 vehicles, including 50 brand new T-72 battle tanks. [7] Though the Russians claimed only two tanks destroyed, they were clearly embarrassed by Khattab’s ability to launch a successful attack deep into Russian Federation territory.

Referred to by Basayev as “head of the Islamic Army of Dagestan,” it is most likely to be Khattab rather than Basayev who conceived the Wahhabist rebellion in Dagestan. The hard core of the fighters also appear to be mujahidin from Khattab’s command. While Basayev commands the headlines in the press, Khattab’s importance is recognized by the Russian military, which claimed to have seriously wounded and captured Khattab in mid-August. The Emir was shortly afterwards seen on TV, mocking reports of his capture and asserting the success of mujahidin operations.

Khattab and Basayev have both threatened to bring the war to Moscow through terrorist attacks on political leaders and installations. The Russians are taking the threats seriously, and have stepped up the visible military presence in Moscow, creating yet another strain on the Russian budget and the fragile political structure. As explosions rip through Moscow, Russian security forces are left wondering whether they are the work of gangsters, radical anti-materialists, Islamic terrorists, or even the product of Moscow’s decaying system of gas lines.

The initiation of the rebellion in Dagestan may yet prove to have been a strategic miscalculation on the part of the Wahhabi volunteers; Dagestan is more likely to dissolve into a bewildering web of ethnic violence than to suddenly rise as one under the Wahhabi banner. The initial success of their campaign will, however, sow the belief amongst the great number of Dagestanis disaffected by corrupt Russian rule that defiance of the militarily inept Russian security forces is possible. Resilient and aggressive by nature, the Wahhabi movement will provide a growing threat to the stability of most of the ex-Soviet Islamic nations ranged along Russia’s southern frontier.

Endnotes

- Andrew McGregor, “Mummies and Mullahs: Islamic separatism in China’s ‘New Frontier’,” Behind the Headlines, 56(4), CIIA, Summer 1999.

- The exact number of ethnic groups or nationalities in Dagestan is a matter of some dispute. Depending on your definition, the number of groups may range from 9 to 200.

- Bagaudin Magomedov, quoted in Reuter-AP, “A call for holy war: Islamic rebels want Russian states liberated,” Toronto Star (Toronto ON), 11 August 1999.

- Marie Bennigsen Broxup, “The Last ghazawat: The 1920-1921 uprising,” in MB Broxup (ed.), The North Caucasus barrier: The Russian advance towards the Muslim world (C. Hurst, London, 1992).

- Boris Nikolin, “The Threat from the Caucasus,” Russian Politics and Law 36, no. 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1998), p. 40.

- Jamestown Foundation Monitor, A daily briefing on the post-Soviet states 3, no. 202, 10-29-97 http://www.jamestown.org/pubs/view/mon_003_202_000.htm, 08-19-99. Blame for the massacre was eventually laid by the Chechen government against a pro-Russian Chechen who had fled to Moscow to evade charges. Geoffrey York, “Chechens believe assassin roams free,” Globe and Mail, Toronto,, 27 January 1998.

- Communiqué from Emir Khattab, “Mujahideen attack Russian base in Dagestan” (Parts 1-2), Azzam Publications, MSA News (12/29/97), http://msanews.mynet.net/MSANEWS/199712/19971228.1.html, 08/19/99. The mujahidin claim to have videotaped the entire operation, as is their practice.