Andrew McGregor

Military History 37(5), January 2021

After a month’s march through the sands, ruins and palm trees that line the Nubian Nile, an invading Egyptian army of cutthroats and mercenaries drawn from across the Ottoman Empire was about to encounter their first real resistance on November 4, 1820. The much-feared horsemen of the Arab Shayqiya tribe were determined the Egyptians would never take their lands. Screaming, they fell upon the army’s Arab scouts with sword and spear, wiping them out. It was a bad start for the Egyptian leader, 25-year-old Ismail Pasha, whose artillery was still being shipped south by boat.

Ismail brought his troops into line against the Shayqiya, who were led by a young girl on a richly decorated camel. It was she who gave the order to attack, a tradition celebrating a fearless 17th century female Shayqiya warrior. The Arabs’ horses pounded their way across the plain, smashing into the Egyptian infantry with such violence that the Egyptian line began to collapse. As disaster loomed, the Egyptians’ formidable second-in-command, the Albanian ‘Abdin Bey, led his horsemen in a series of desperate counter-charges. The Egyptian infantry rallied and began to pour fire into the Shayqiya. The invaders triumphed, only to begin what one of their number later described as “twelve months of misery and starvation.”

Ismail brought his troops into line against the Shayqiya, who were led by a young girl on a richly decorated camel. It was she who gave the order to attack, a tradition celebrating a fearless 17th century female Shayqiya warrior. The Arabs’ horses pounded their way across the plain, smashing into the Egyptian infantry with such violence that the Egyptian line began to collapse. As disaster loomed, the Egyptians’ formidable second-in-command, the Albanian ‘Abdin Bey, led his horsemen in a series of desperate counter-charges. The Egyptian infantry rallied and began to pour fire into the Shayqiya. The invaders triumphed, only to begin what one of their number later described as “twelve months of misery and starvation.”

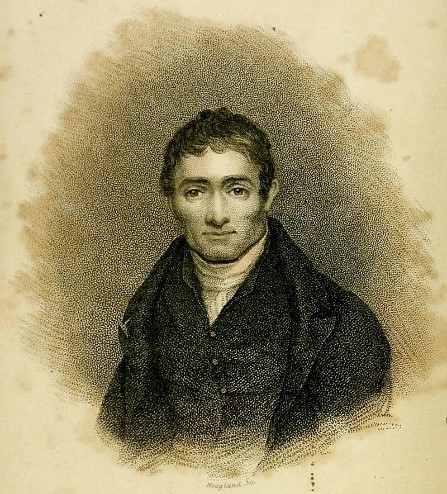

The Egyptian expedition to Sudanese Nubia included three American mercenaries, including former US Marines officer George Bethune English, though illness kept him from the battlefield that day. The Massachusetts native, a convert to Islam, related his experiences as an artillery commander in Sudan in his 1822 memoir, A Narrative of the Expedition to Dongola and Sennar, yet 190 years after his death, English remains an enigma; was he mercenary, spy, or sincere convert to Islam?

English had taken degrees in law and divinity at Harvard College. After being exposed to a collection of 17th century documents that questioned important aspects of Christianity, English wrote a book critical of Christian doctrines in 1813. The work elicited howls of outrage in Protestant New England and English was turfed from Harvard and excommunicated from his church. His belief that Islam was a moral system drawn from the Old and New Testaments, “modified a little, and expressed in Arabic,” proved toxic to his reputation.

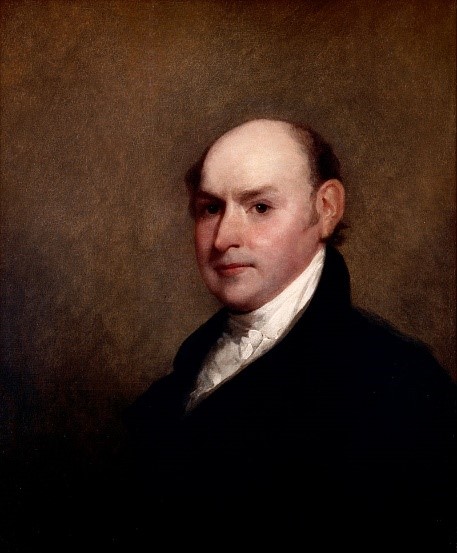

John Quincy Adams in 1818 (George Stuart)

John Quincy Adams in 1818 (George Stuart)

US Secretary of State John Quincy Adams made an unexplained intervention on English’s behalf by commissioning him as a second lieutenant in the US Marines in 1815. English served in the Mediterranean in 1816-17 and was promoted to First Lieutenant. He resigned and moved to Constantinople shortly afterwards in mid-1817, but was still listed on the Naval Register until 1820. Was English acting as Adams’ secret agent in the Middle East?

By 1820, English was in Egypt, where he converted to Islam, changed his name to Muhammad Effendi and used the influence of British Consul Henry Salt to join the Egyptian army as a senior officer of artillery. He was joined by two American sailors who either deserted or were reassigned from the five warships in the US Mediterranean squadron. Known only by their adopted names, New Yorker Khalil Agha and the Swiss-born Ahmad Agha converted to Islam and acted as English’s servants. By the time English enlisted he was fluent in Arabic and Turkish, the languages of the Egyptian Army.

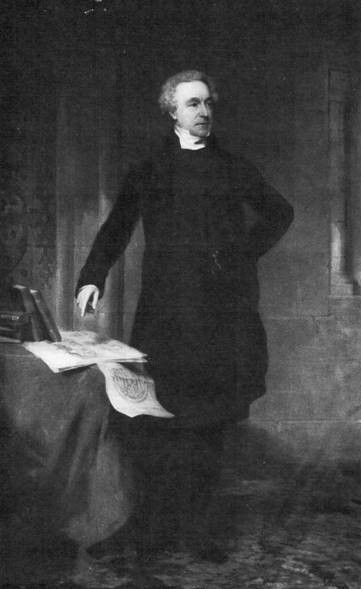

Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (David Wilkie)

Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (David Wilkie)

Expanding Egypt’s borders far south into Sudanese Nubia was part of a larger effort by Egyptian ruler Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha to build a family dynasty to rival the Ottomans in Constantinople. He and his sons would eventually seize Sudan, parts of the Red Sea coast, all of Syria and Palestine and the holy cities of Arabia.

Massacre of the Mamluks at the Cairo Citadel (Horace Vernet)

Massacre of the Mamluks at the Cairo Citadel (Horace Vernet)

The second purpose of Muhammad ‘Ali’s expedition was to eliminate the Mamluks, a military slave-caste that ruled Egypt before being treacherously slaughtered by the Pasha. The survivors fled to Nubia, where they arrogantly forced Nubian farmers to grow their food in the blazing sun while they cooled themselves on a huge raft anchored in the middle of the Nile.

The third purpose involved the creation of a new Egyptian army of black slaves, something Napoleon had tried only a few years earlier. The Pasha decided to seize thousands of Sudanese to fight his own wars of conquest and those he was obliged to join on behalf of his suzerain, the Ottoman Sultan.

The Egyptian invasion force consisted of 4,000 men, with 120 artillerymen serving ten field pieces, two small howitzers and one mortar. The infantry included Turks, Kurds, Albanians, Circassians, Greeks, Syrians and 700 “Maghrabis” (mercenaries from Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco). Turkish cavalry and some 700 camel-mounted ‘Abbadi Arabs completed the force.

Six cataracts lie between Aswan (where Nubia begins) and the intersection of the White and Blue Niles. Each cataract consists of a series of deadly rapids and waterfalls created by granite rock. Thousands of Nubians were forced to help haul the expedition’s boats over these obstacles.

The expedition left on October 3, 1820, with 120 boats carrying the expedition’s supplies and ammunition. Within days, English was struck with severe ophthalmia, an eye affliction which caused such pain that he was unable to sleep without doses of opium. Ismail’s army went on without him.

English joined a group of French army surgeons headed south to join Ismail, but they suffered badly at the Second Cataract, where crocodiles gathered to enjoy an unexpected feast of drowning sailors.

Shayqiya Warrior (Frédéric Cailliaud)

Shayqiya Warrior (Frédéric Cailliaud)

To continue south, the expedition had to defeat the Shayqiya, whom English described as a “singular aristocracy of brigands.” They had ruled the Dongola region from their cliff-top castles for over a century, forcing the Nubians to grow their food and serve as their infantry. In battle, they carried two spears, a German-made straight-sword, and a hippopotamus-hide shield. Haughty and dismissive of death, they were not overly concerned when Ismail demanded that they abandon their weapons and till the soil.

After the victory at Kurti, Ismail thought to please his father by offering a reward for every pair of enemy ears. Once his army had exhausted the supply attached to the dead and wounded, they spread through the villages, separating women and children alike of their ears. Bags full of these grisly trophies were shipped to Cairo, where an angry Muhammad ‘Ali reminded his son that such behavior was incompatible with the modern European-style army he was trying to build. English’s narrative says nothing of these atrocities.

The Shayqiya regrouped a month later at Jabal Daiqa to face Ismail a second time. The Nubian infantry was numerous, but the experienced men had been lost at Kurti. Their replacements were encouraged by holy men who sprayed them with magic dust to make them immune from death. The infantry advanced with reckless courage against Ismail’s field artillery, which had finally joined the army (English was still absent). As they reached the blazing guns, the foot-soldiers were blasted to pieces at point-blank range. The attack faltered, the Shayqiya left for the south and the Nubian infantry were left to be slaughtered by ‘Abdin Bey’s cavalry. Defeated, the Shayqiya proposed being taken into Egyptian service as irregular cavalry rather than be forced to take up the shameful occupation of farmer. The offer was accepted.

English described the Shayqiya leader Sha’us, reputed to be the greatest warrior on the Upper Nile, as “a large stout man, pleasing of physiognomy, though black…” The American was stunned by his ability to swim his entire cavalry force across the Nile.

Even as English recovered from his ophthalmia, he was struck with bloody dysentery that left him extremely weak. As his condition improved, English visited the little-known temples, castles and pyramids that lined the Nile. Khalil inscribed the name of “Henry Salt” on various ancient monuments along the way. This was a common method to establish a claim to a certain antiquity, which would be retrieved later for shipment to Europe. Meanwhile, many of the sailors used their shore-time to beat and rob local men and rape their women. The “insolence” of villagers who refused to turn over their grain angered English, who suggested that those soldiers who pillaged and murdered “were not much to blame.”

George Waddington (Richard Say)

George Waddington (Richard Say)

Two Englishmen, George Waddington and Barnard Hanbury, received permission to join the army on its way south on November 26. English was eager to meet them, but Waddington made it clear he had no respect for a man who abandoned his religion. Waddington reported that the land behind the Egyptian army was strewn with the rotting bodies of beasts and men, some still with rope around their necks. The countryside was silent and the wells fouled by decaying corpses.

Waddington’s memoirs included scathing criticism of English and his religious pretensions and/or confusion. He described English as a pale and delicate-looking man who had taken on the grave and calm demeanor of the Turks. Waddington said he later learned English was a Protestant who had adopted various strains of Christianity before becoming a Jew and an orthodox Muslim in succession. He suggested English would soon turn Hindu in his “tour of the world and its religions” and would ultimately die an atheist. English claimed Waddington later gave him an apology, but the remarks stuck.

Muhammad ‘Ali ordered Ismail to march on the Blue Nile kingdom of Sennar and its fabled riches as quickly as possible. English joined the Egyptian force on a forced march across the Bayuda Desert to Berber, a means of shortening the distance covered by the great bend of the Nile, but one that left the New Englander with severe sunburn and re-aggravated ophthalmia.

The boats were left to make their way through the two worst cataracts – the 4th and 5th, a punishing trip of 57 days. Khalil and Ahmad were separated from English at this point and forced to accompany the boats. Both suspected the machinations of Ismail’s personal doctor (“the Protomedico”), a Smyrniot Greek and skilled poisoner, but their skills as sailors may have prompted the decision. Without intending to, Khalil became the first Westerner to travel the entire length of the Nile from the Mediterranean coast to Sennar.

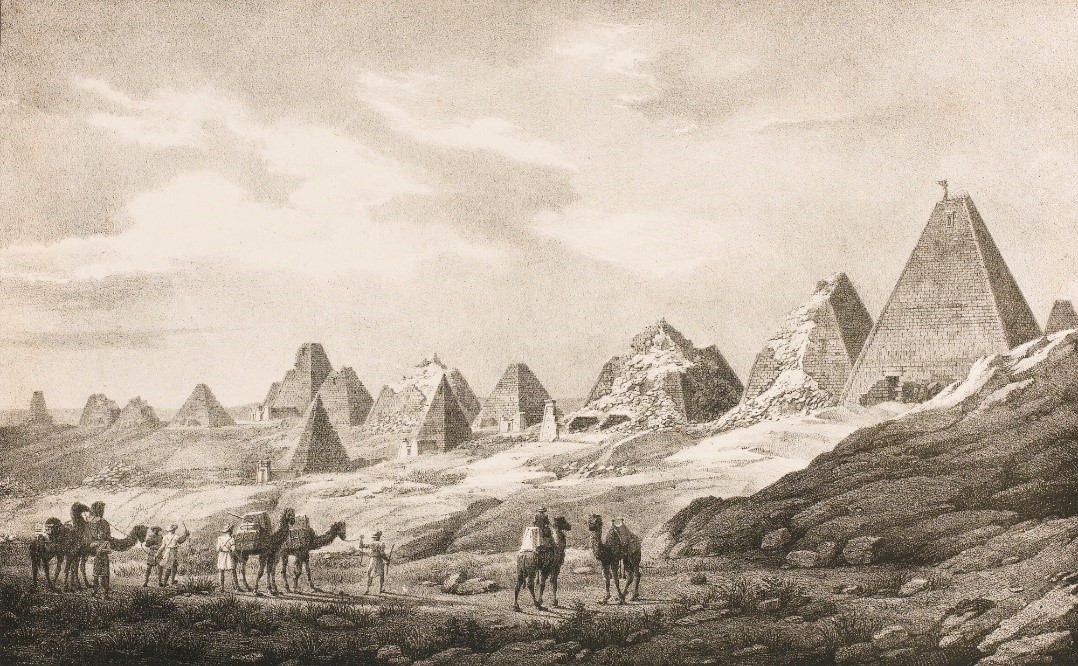

Egyptian Troops at the Pyramids of Meroë (Frédéric Cailliaud)

Egyptian Troops at the Pyramids of Meroë (Frédéric Cailliaud)

Ahmad Agha died at the 4th Cataract. Khalil believed he was poisoned by the Protomedico after a quarrel. The most competent physician on the expedition, the Genoese Dr. Andrea Gentile, had already met the same fate when the Protomedico decided it was easier to poison him than repay a loan. The Protomedico had sold off the contents of the expedition’s medicine chest in Cairo cover his debts and surrounded himself with Greek villains. Other Europeans feared for their lives, including French geologist Frédéric Cailliaud, who used the expedition to record the legendary pyramids of Meroë: “Death seemed to want to claim all the gentlemen around me.” The Italian Domenico Frediani died as a “chained maniac” in Sennar after a dispute with the Protomedico. Ismail was aware of the doctor’s improprieties, but found him useful as a spy and henchman.

Eventually the army reached Berber, home to a hundred fugitive Mamluks. Most fled, but the rest submitted and accepted an offer to return home or serve as Ismail’s bodyguards. In Berber, female slaves were offered to the soldiers for a dollar a night. A chief’s wife gave English the opportunity to bed both her married daughters; English claimed his sunstroke saved him from temptation, but the daughters concluded English was rajil batal, a good-for-nothing man.

Rough handling of the transport animals led to their rapid loss; to save the artillery horses for battle, English ordered the guns to be pulled by camels. The army was now joined by Malik (king) Nimr of Shendi, “very dignified in his deportment and highly respectable for his morals” according to English.

To reach the south bank of the Blue Nile, Ismail spent over two days ferrying his army across the mile-wide White Nile by boat. The Shayqiya swam their horses across the river, as did the ‘Abbadis with their camels. A Turkish officer who decided he could do the same lost 70 horses and a number of men.

The march to Sennar lasted thirteen days, with the men on the move from 2 AM to 10 AM, at which point the heat became too intense. The only food was durra, a local grain requiring much preparation.

Sultan Bady of Sennar (Frédéric Cailliaud)

Sultan Bady of Sennar (Frédéric Cailliaud)

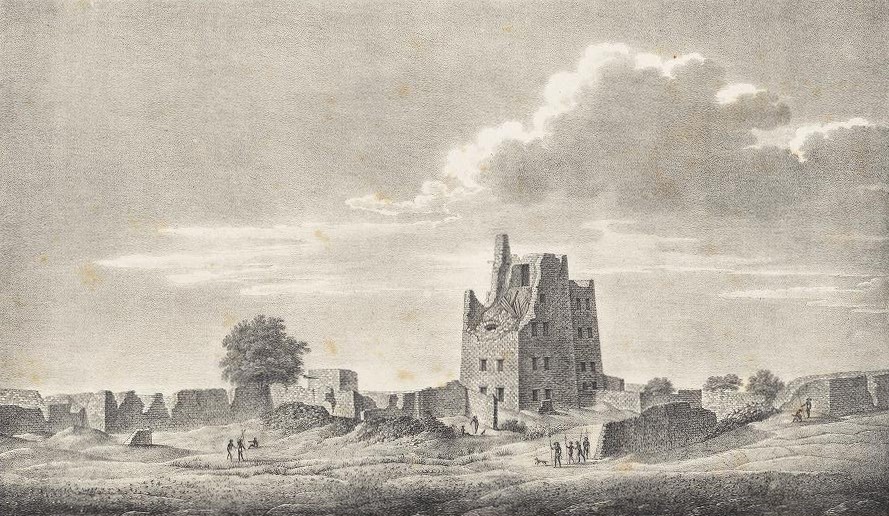

The 26-year-old Sultan Bady of Sennar (recently freed from 18 years of confinement) came out to greet Ismail and escort him into the legendary city. The magnificence of the trappings and garments of the royal entourage seemed a promising sign. The troops believed they would now reap the rewards due them after a brutal 1250-mile march from Cairo and approached the city with cries of joy and volleys of musket fire. Their delight was dashed when they realized the glory days of Sennar were over. The city was little more than a heap of broken ruins, its population inhabiting some 400 squalid huts. The only buildings of any substance were the half-ruined brick palace and mosque. Of gold and riches, there were none.

The Palace of Sennar (Frédéric Cailliaud)

The Palace of Sennar (Frédéric Cailliaud)

With no pay for eight months and only durra to eat, the soldiers began to flog their uniforms to buy food or to pilfer supplies to sell in the market. Ismail’s worsening mood was reflected in the growing numbers of headless bodies dumped in the market. Soldiers impaled anyone who showed the slightest sign of resistance. English overheard some scandalized female observers declaring such punishments were fit only for Christians.

Flying columns raided the still-defiant hinterland. Egyptian firepower cut down hundreds of armored warriors and the army shipped thousands of men, women and children north to the Cairo slave markets. English, a native of abolitionist New England, acquired a slave of his own.

English did not accompany the raids; instead, he spent his time persuading Ismail to allow him to return to Cairo on health grounds before the miserable four-month rainy season began. He was not held back by the charms of the women of Sennar, whom he described as “the ugliest I ever beheld.”

Meanwhile, Ismail ordered two captured chiefs to be impaled; the first awaited his end by reciting the Muslim profession of faith; the second cursed and insulted his executioners. When he could no longer speak, he spat at them. Other chiefs addressed the Pasha with presumptuous questions; one asked whether Egypt was so short of food that it was necessary to come all that way to take theirs!

After a harrowing return trip to Cairo, English went to see Muhammad ‘Ali to collect the funds he was owed for his military service, but found him in a foul temper; he had just received word of the murder of his son Ismail in Nubia by Malik Nimr, who Ismail had grievously offended. Broke and desperate, English called on Henry Salt, who provided him with funds to return home in exchange for his narrative manuscript and various artifacts. Salt published the work, which English dedicated to him, “my fatherly friend in a foreign land.” Khalil composed his own unpublished account of the expedition, only recently discovered in Salt’s Papers at the British Library. He remained in Egypt, living as a Muslim and continuing to serve Muhammad ‘Ali.

Pliny Fisk, an evangelical missionary working in Egypt, met English after hearing he was ready to “return to his country and the religion of his Fathers.” The penalty for abandoning Islam or the army was death, but English found his way to Salt’s Consulate, where a network helped smuggle remorseful converts out of Egypt. English joined Fisk on a ship bound for Malta, playing the part of his servant. Fisk, who normally recorded everything, recorded nothing of the long shipboard conversations with English that appear to have shaken his own faith in Christianity. English, apparently, had not abandoned Islam entirely.

English’s account of his adventures in Sudan went largely unremarked. It had the preoccupation of an intelligence report with topography, but revealed nothing of its author, who freely admitted he missed the main engagements of the campaign. Considering his background, it is bizarre that no religious observations were made. English assured readers of the high regard in which he was held by Ismail, but his service record suggests otherwise – he missed the two main battles of the campaign, was typically behind the main force of the army, did not accompany the slave-raiding parties operating out of Sennar, and “demanded” a return to Cairo.

English’s father and friends tried to pave the way for his return to America by writing letters to the newspapers praising his “achievements” in Sudan while casting doubt on the sincerity of his conversion to Islam.

English did not live as a Muslim on his return, but published yet another work critical of Christianity against the objections of his remaining friends. Adams continued to act as his patron and sent English on a trade mission to Constantinople in 1822, where he appears to have resumed life as a Muslim.

As president, Adams continued finding employment for English; in July 1828 he engaged him as a carrier of secret dispatches to the US Navy in the Mediterranean. Two days later, however, English was driven off in disgrace. Typically, there is no record of what happened, only an entry in Adams’ journal referring to “mortifying” misconduct by English: “Notwithstanding his eccentricities, approaching to insanity, I have continued to favor him till now. I can no longer sustain him.”

Was English working for the British, the Americans, both, or neither? Was he sincere in his conversion to Islam (prepared with enormous intellectual effort), or was this merely a means to infiltrate Muhammad ‘Ali’s expedition to Sudan, a region of growing interest to Britain? Some American Muslims maintain that English was “America’s first Muslim” and kept true to his faith until his death.

English’s death only two months after his dismissal deepens the mystery. His obituary provides no clue as to how the 41-year-old perished; suicide or illness seem possible. His memoir shed no light on his motivations and his religious works passed into obscurity with him. No portrait seems to survive of the shadowy American mercenary – fitting for a man who took so many secrets with him to the grave.