Andrew McGregor

AIS Military History

October 12, 2025

Sampans glide silently in the darkness over an inland waterway in north Vietnam’s Red River delta. Five Frenchmen and 120 Vietnamese commandos are on their way to make a deep behind-the-lines raid on Ho Chi Minh’s communist Viet Minh guerrillas. Their mission involves intelligence collection, seizing prisoners for interrogation and sowing confusion behind enemy lines. Among these nocturnal predators are many former Viet Minh prisoners; the lone French officer and his NCOs operate in the knowledge they may be killed by their own men at any time. This is life in the “Commandos of North Vietnam” (1951-54), a French precursor to the American Green Berets.

Sampans glide silently in the darkness over an inland waterway in north Vietnam’s Red River delta. Five Frenchmen and 120 Vietnamese commandos are on their way to make a deep behind-the-lines raid on Ho Chi Minh’s communist Viet Minh guerrillas. Their mission involves intelligence collection, seizing prisoners for interrogation and sowing confusion behind enemy lines. Among these nocturnal predators are many former Viet Minh prisoners; the lone French officer and his NCOs operate in the knowledge they may be killed by their own men at any time. This is life in the “Commandos of North Vietnam” (1951-54), a French precursor to the American Green Berets.

When General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny became commander-in-chief of the French Far East Expeditionary Corps in December 1950, French forces had been struggling for nearly six years to re-establish control over the Indochina colonies. Japanese forces destroyed the French occupation army in 1945, leaving a post-war power void exploited by Ho Chi Minh’s communist Viet Minh. The arrival of de Lattre, a legendary French soldier known to his men as “King Jean,” reinvigorates the badly demoralized Expeditionary Corps.

De Lattre, realizing the futility of following the old rules of combat, clears out incompetent officers and introduces new ideas, weapons and tactics, including a plan to create a series of new commando groups for use in northern Vietnam (“Tonkin”). These units, composed almost entirely of Vietnamese troops with a few French officers or NCOs in command, take the war to the Viet Minh using their own methods and intimate knowledge of the terrain. It is a war of no quarter, fought almost exclusively at night by men disguised as the enemy, men with a special gift for killing in the dark.

Origins

Even before the liberation of Paris, Free French leader General Charles de Gaulle was planning to re-establish French control of the Indochina colonies of Laos, Cambodia and the three regions of Vietnam – Cochin China in the south, the central region of Annam and the northern region of Tonkin. In 1944, the first Free French commando groups, officially the Corps Léger d’Intervention (C.L.I.), but better known as Gaurs (wild buffalo), are dropped into Japanese-occupied Laos. Torture is inevitable if captured and cyanide pills are regular issue. [1] Some of the commandos are highly trained veterans of the Free French companies of the British Special Air Service (SAS) and continue to wear the regiment’s green berets.

On March 9, 1945, the Japanese Army depose the French Vichy government in Indochina, slaughtering entire garrisons in surprise attacks. Two French Gaur groups are dropped into Tonkin by British planes to assist the fighting withdrawal to China of a column of starving and bloodied French colonial troops. Few of the Gaurs survive, most dying in suicidal attempts to delay the Japanese.

These early commandos are reliant on British training, transport and equipment, as the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS – predecessor to the CIA) initially supports Ho Chi Minh’s nationalist guerrillas over the French. This preference is in line with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s vision of a post-war world where national self-determination will replace European imperialism.

Battle of the Day River

After years of bitter fighting in Vietnam’s jungles and mountains, it is the performance of mixed groups of French and Vietnamese commandos at the Battle of the Day River (May 28-June 18, 1951) that convinces General de Lattre to make the commandos a formal part of the French Expeditionary Corps.

The Limestone Crags at Ninh Binh

The Limestone Crags at Ninh Binh

When the Viet Minh’s 320th Division launches an offensive along the Day River, they are opposed by small French units holding two limestone crags at Ninh Binh. One of the peaks is held by “King Jean’s” son, Bernard de Lattre, who is following his father’s order to hold the French position at all costs. A mostly Vietnamese commando led by a massive young French NCO, Roger Vandenberghe, is called upon to reinforce the young lieutenant by climbing the crag under heavy fire. Machine-gun fire sends climbers plummeting down the cliff, and eventually finds Vandenberghe. Wounded, he signals his second-in-command, Sergeant Tran Dinh Vy, to finish the assault. The slight but formidable sergeant is a former seminarian who has become a master of guerrilla tactics.

During the attack, the bleeding Vandenberghe retrieves the body of his friend, Bernard, a victim of Viet mortar fire. The recovery ingratiates Vandenberghe to General de Lattre, who is deeply disturbed by the loss of his only child. [2] From this point, de Lattre acts as a patron to Vandenberghe, whose savage way of war is bringing him close to dismissal by French commanders alarmed by his methods. “King Jean,” who will declare Vandenberghe “the greatest soldier in Indochina,” authorizes the creation of formal French Army commando units on July 2, 1951.

Elsewhere at Ninh Binh, two battalions of Viet Minh, the lead elements of Giap’s offensive, run into a naval commando unit on May 28, 1951, the 76-man Commando François led by Lieutenant Albert Labbens. Cornered in an abandoned church, the commandos hold off an overwhelming communist force for 24 hours, allowing the French to rush forces to the area and stop the offensive. The end of Commando François comes when 29 mostly wounded survivors make a sally from the church after running out of ammunition. To honor their sacrifice, the commando was never reconstituted. [3]

The Battle of the Day River ends three weeks later as a disaster for Giap, who leaves 12,000 dead behind. It is a tactical lesson for the communist general, but cements the reputation of the French commandos.

Training

Responsibility for organizing the commandos is handed to Louis Fourcade, commander of the 1st Battalion of Colonial Paratroopers. Fourcade spent WWII as an officer in the Vichy colonial army in Indochina, with secret contacts to Free French agents working across the border in China. He was involved in the desperate fighting against the Japanese in the last months of the war.

The new commando units normally include 120 Vietnamese under a European officer or, more commonly, a senior NCO, aided by four other NCOs and at least one European radio operator. Viet Minh prisoners are given the chance to avoid heavy labor by volunteering to join the new commando groups. This is a highly dangerous practice; while it brings on board men who are intimately familiar with the enemy and his methods, it also hands arms to men who might wait months before suddenly turning on their leaders. Sleeping becomes as precarious for the commando leaders as a fire-fight with the enemy. To let one’s guard down for a minute is to invite death.

Training is carried out at the Vat Chay commando school by SAS veteran Captain Michel Legrand. Later training of the commandos is undertaken by one of the hardest men in the French Army – Yvan Tommasi, an Algerian-born officer of the Colonial Paratroops and a Free French veteran of fighting in Africa and Europe. In 1950, he loses his right hand while seizing a bomb from the hands of a trainee who had mistakenly set it to explode. Rather than retire, Tommasi continues to jump and is appointed trainer of the commandos in February 1952. Captured leading a raid in January 1953, Tommasi spends six months in a Viet Minh prison camp. There, he is singled out by French communist and turncoat Georges Boudarel, who tries to break him by forcing him to dig all the graves for the camp with his left arm and the stump of the right. Tommasi is kept busy; 85% of the prisoners in Camp 113 die from torture and mistreatment while being forced to sing the praises of Ho Chi Minh. [4] Tommasi survives and continues to serve in the colonial paratroops in Africa until 1966. [5] Amazingly, the unrepentant Boudarel is hired as a professor by a Paris university after the war.

The commandos are taught to fight at night. As Captain Delayen of Commando 13 recalled:

After having overcome the visceral fear of the night, and the completion of special training requiring the greatest discipline, the [Vietnamese] auxiliaries were convinced that, lightly armed as they were, only night action could allow them to dominate an adversary unaccustomed to not be the only ones operating at night. [6]

Internal cohesion is achieved by recovering commando families living in Viet Minh-occupied zones, building schools, pagodas and married quarters beside the commando base, and forming the atmosphere of “a big family” through the cultivation of vegetables and the raising of chickens and pigs.

Operations

The commandos do not perform normal military duties such as routine patrols or guarding military posts. When necessary, they operate in conjunction with regular troops on larger military operations. [7] The commandos use weapons supplied by the English and Chinese weapons captured from the Viets, including Thompson machine-guns and WWII-era Sten guns. Grenade launchers and small 50- or 60-mm mortars complete the light armament of these highly mobile units. Many wear the black cotton uniform of the Viet Minh, complete with sneakers, palm helmets and a Red Star insignia.

To gather intelligence, the commandos venture deep into enemy territory to observe movements, take prisoners and disrupt communist political networks. Attendees at Viet Minh meetings live in fear of French commandos bursting in, firing their Thompson machine-guns from the waist. The commandos are taught to aim at the feet of their targets in close combat, as the Thompsons tend to jump up when fired.

In his memoir, Sergeant Bernard Gaudin of 25 Commando describes a night ambush during a deep raid on the Viet Minh. Ambushes mean hours of silent misery, uniforms soaked by an endless drizzle. Nerves are on a razor edge as eyes strain to detect movement in the inky darkness. The torment of mosquitoes is unrelenting but must be endured noiselessly:

Canh, my faithful corporal, whispers in my ear: “Chief, there are a lot of Viets.” (…) Here we go, all the Commandos who are waiting for this break loose. We can finally cough, yell – it’s recommended. The bursts and explosions of grenades tear the night apart. Immediately, there is a pack of Viets on the mat. We hear them shouting orders to try a maneuver but we shoot at everything that moves. [8]

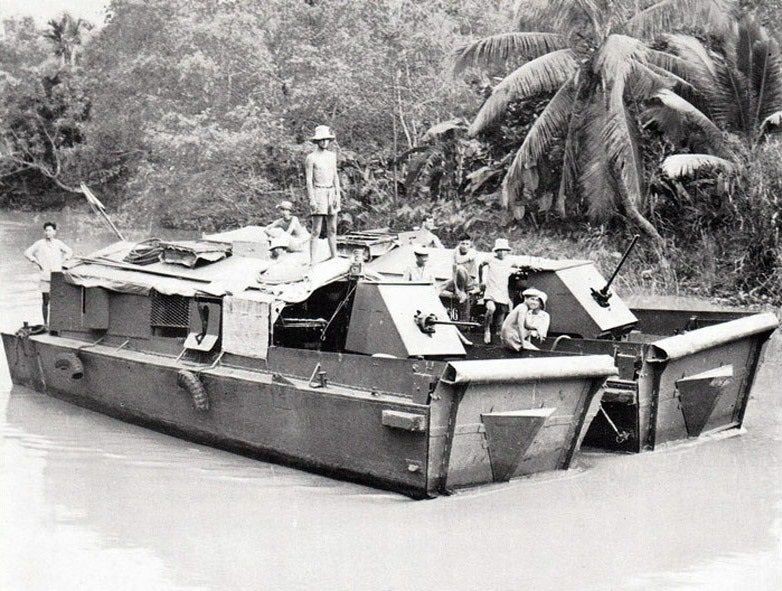

With prisoners taken and the Viet Minh column destroyed, Gaudin leads his men back by a different route. The waiting Viet Minh begin to rain down grenades as they cross a rice paddy. Two of his men are killed before fire rakes the Commando from sharpshooters in the trees. A Dinassaut (armored landing craft) makes a welcome appearance on the river and lays down heavy fire until the shooting stops. The Commando returns to camp, where a blazing fire enables the start of “Operation Leech,” as the men burn off blood-engorged parasites with a cigarette, dropping them to sizzle in the flames. [9] Gaudin’s raid yields a treasure-trove of intelligence documents, including the cipher to the Viet Minh code. At other times, it is the commandos who are the victims; when Commando 34 operates in Laos in support of the besieged French garrison at Dien Bien Phu, Sergent-Chef Müller leads it into a devastating ambush, losing 68 of its 107 men, including Müller.

Dinassaut with a Mixed French/Viet Crew

Dinassaut with a Mixed French/Viet Crew

The Dinassaut are surplus American shallow-draft LCMs (Landing Craft Mechanized), modified to bring heavy firepower to support infantry and commando operations in the shallow waterways of the Red River Delta. For this, the Dinassaut deploy heavy machine guns, 81mm mortars and even tank turrets welded onto the crafts. They save more than one commando group and are effective enough to serve as a model for later American river operations in the south.

The physical challenges alone are daunting on operations and exacerbated by a shortage of medicines and medical personnel. In the infernal heat, unbearable prickly heat is enough to drive a man mad. Clothing is little better than a curse; damp clothes and web gear rubbing on skin creates raw patches that quickly become infected before the flesh begins to rot. Boils, warts and the festering lumps provided by stinging and biting insects complete the assault on the skin. Internally, the body is host to large worms that have a disconcerting habit of popping out through the mouth as well as the anus; externally, the body sustains legions of leeches, mindless and ubiquitous creatures devoted to bleeding a man dry. Eye diseases that deprive a man of sight are rife; malaria and a multitude of tropical ailments make delirious fever an almost normal condition. Amoebic dysentery, endemic in the polluted rice paddies and streams that double as toilets for the locals, provides a slow and demoralizing death.

Despite these challenges, it is necessary for the leaders of the commandos to continually demonstrate physical and mental strength or risk losing the men under them. For officers of the French regular army, this dirty, stressful and highly dangerous work is commonly viewed as more likely to lead to an early death than promotion. Leadership roles are thus opened to audacious NCOs who may not have graduated the French St. Cyr military academy, but are capable of innovation, independent action and, most of all, killing Viet Minh. Contrary to expectations, the experience of the surviving commando leaders propels them rapidly through the ranks after the French withdrawal from Indochina. Men who understood the “new warfare” developed in Indochina would be needed in Algeria.

In response to the pressure of the commandos, the ever-adaptive Viet Minh create a counter-commando force, the Dich Van. This covert unit is assigned the task of infiltrating native troop formations aligned with the French Expeditionary Corps, often by intimidating the families of pro-French fighters. [10] Dich Van propaganda teams recruit Foreign Legion deserters to persuade French Expeditionary Corps prisoners in French, German and other European languages to adopt Marxist ideology and take up arms against their former comrades.

The Wild Boar

Several French commanders achieve fame in this highly unconventional form of fighting, one fought with knives as much as sub-machine guns. One of these is a solid, thick-set Corsican lieutenant, Charles Alphonse Rusconi. For his ferocious fighting style, the Corsican is known as Le Sanglier, “the wild boar.”

Rusconi begins his military career in 1936 by joining the Colonial Army’s 10th Regiment of Senegalese Tirailleurs (riflemen). He leads several daring commando raids behind German lines in 1940 before being wounded and captured. Escaping only two months later, he joins the French forces in Indochina in 1948, forming Commando 24 from Viet Minh prisoners and Black Colonial Army troops from Mali. The latter, mostly large men, say their commander is “small, but cunning.” Through unrelenting attacks that shatter Viet Minh morale, his group forces a significant decline in communist activity in his zone of operations.

The 33-year-old Rusconi, survivor of four wounds, is killed in February 1952 when one of his commandos, a former Viet Minh officer influenced by the Dich Van, opens a way into the camp for a company of Viet Minh. Rusconi and most of his command fall in vicious hand-to-hand fighting, knives, fists and boots flailing to the last.

The Black Tigers

Childhood for Roger Vandenberghe and his brother Albert is extremely difficult. Born in a Paris slum, their father dies from tuberculosis in 1939. Their mother, a Spanish Jew, is sent by Vichy authorities to a Nazi death camp. With little education, the boys join the French Resistance as mere teenagers, followed by service as commandos in General de Lattre’s First French Army in Alsace and Germany. After the war, Vandenberghe and his brother arrive in Vietnam as part of the 6th Colonial Infantry regiment. Roger is immediately taken with the country, a place far different from the crowded tenements of Paris. Already decorated with the Croix de Guerre for his Resistance work, Vandenberghe quickly makes sergeant in command of a unit of Vietnamese auxiliaries that becomes Commando 24, “The Black Tigers.”

Vandenberghe’s nemesis in Vietnam is Chapuis, a former French paratrooper who deserted to the communists. In June 1948, Chapuis kills Vandenberghe’s younger brother, his only family in the world. The deserter is captured by Vandenberghe in 1951 and sent to the French post at Nam Dinh, where he escapes and returns to the Viet Minh.

Vandenberghe’s most famous exploit comes when one of his turned commandos reveals the location of a Viet Minh command post. Vandenberghe allows himself to be bound as a prisoner and carried along by his men in Viet Minh uniform, passing through checkpoints by insisting they are going to collect the reward on Vandenberghe’s head. Once inside the command post, Vandenberghe is released; he and his men slaughter everyone there, seizing a treasure trove of documents and weapons. [11]

Vanderberghe Meets an Astonished General De Lattre at Phu Ly

Vanderberghe Meets an Astonished General De Lattre at Phu Ly

This fearsome NCO has little use for the officers of the French army, but is impressed by the leadership of General De Lattre, his former commander in France. He leads his men 12 miles through enemy territory to see the general at a gathering in Phu Ly. The general is astonished to see this towering European in a Viet Minh uniform and helmet. Vandenberghe explains his appearance as necessary while operating almost exclusively behind enemy lines. De Lattre is taken by this odd but unforgettable warrior, remarking a few days later: “It’s a bit as if a tiger, in addition to its fangs and claws, received a hunting license…” [12]

The French commandos fight brutal, no-quarter battles in a tropical darkness where the normal conventions of war hold no sway. Even in these conditions, Vandenberghe stands out for waging a vicious and pitiless war using methods the French command find disturbing. He drives his men hard; complaints are met with a reminder that, without him, his turncoat troops “would be in jail or eaten by maggots.” [13] Desertions are frequent and Vandenberghe is shot in the back by one of his own men in 1949. After returning from medical treatment in France he becomes even more unrestrained, his NCOs struggling to keep him in check, especially in his dealings with the civilian population. Vandenberghe pays little heed to the criticism of his methods by French officers, insisting that war was about killing, so they were best to leave him to it. [14]

Vanderberghe and Rusconi in Hanoi, February 7, 1952

Vanderberghe and Rusconi in Hanoi, February 7, 1952

Paratrooper Phillipe de Pirey recalled a parade held in honor of General de Lattre that featured the Vandenberghe and Rusconi commandos, “most striking” in Viet Minh-style black shorts and shirts, topped with Latanier (palm) helmets with red stars on a yellow background. Beside their Sten-guns with fifty round magazines, numerous knives and grenades hung from their belts. Once onlookers managed to overcome the shock of witnessing these former Viet Minh warriors parading in the streets of Hanoi in the uniforms of the enemy, it was possible for de Pirey to admit “the men in these units looked rather splendid.” [15]

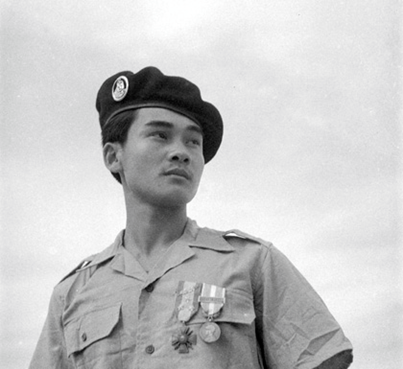

Tran Dinh Vy – Tiger and Legionnaire

Tran Dinh Vy – Tiger and Legionnaire

On January 6, 1952, at a time when most of Commando 24 is on leave, Vietnamese sentries who had managed to infiltrate the unit allow a Viet Minh team that may include the deserter Chapuis to enter the camp. The assassins move silently and Vandenberghe is butchered in his sleep by a former Viet Minh officer under his command. Ten others are killed; the few wounded who survive include Sergeant Tran Dinh Vy, who goes on to serve in the army of South Vietnam. Arriving in France after the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975, this exceptional soldier joins the French Foreign Legion, attaining the rank of colonel.

Commando 24 in Viet Minh Uniforms

Commando 24 in Viet Minh Uniforms

Wounded seven times by bullets, grenades and mines before his death, Vandenberghe becomes the most highly decorated French NCO of the 20th century. An obituary in a leading Paris newspaper notes that the war enabled Vandenberghe to “find in the combats of the jungle the blossoming of his barbaric personality.” [16] Five days after Vandenberghe’s death, General de Lattre dies of cancer in Paris and is laid to rest alongside his son, Bernard, marking the end of the short but eventful relationship between the king, his prince and the tiger who served them.

End of the North Vietnam Commandos

After the fall of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, the French command decides to evacuate the southern half of the Red River Delta. Hundreds of Vietnamese begin to desert the French forces. Two sections of Commando 35 murder their French commander, Lieutenant Nedelec, and two French NCOs before joining the enemy in July 1954. [17]

Général Salan and the Commando Yatagan in Algeria

With the French war over, the native remnants of the commando groups assemble at Haiphong and are sent to South Vietnam to form the 1st Battalion de Marche des Commandos (BMC). Their French officers and NCOs find themselves in demand and are sent to Algeria to continue French experiments in counter-insurgency. Commando 13’s Captain Jean-Louis Delayen forms the Yatagan Commando in Algeria, a French-led unit of Algerian Muslims operating along the lines established by the North Vietnam commandos. A second-generation member of the French colonial infantry, Delayen finishes his career in 1978 as one of the most decorated soldiers in the French army.

Tomb of Roger Vanderberghe, Pau, France (Joel Herbez)

Tomb of Roger Vanderberghe, Pau, France (Joel Herbez)

Vandenberghe’s remains are repatriated to France from the Nam Dinh cemetery in 1989, where they are interred in a monument honoring the “Black Tiger” at the National NCO Academy in Pau.

By the end of the war in 1954, Viet Minh losses to the Nord Viet-Nam commandos include 3,664 dead, 481 wounded and 4,649 taken prisoner. European commando losses include 73 dead, 25 wounded and 6 missing. Losses of Vietnamese commandos in French service appear not to have been recorded but could only be described as substantial. [18]

Louis Fourcade, who had organized the commandos, honors them after the war: “Thanks to their ardor, their contempt for danger, the initiative of their leaders, the courage and undeniable devotion of their men, the North Vietnam commandos acquired and deserved their reputation of being always into the breach.” [19]

NOTES

[1] Jean le Morillon, p.134.

[2] Bernard Fall, p. 45.

[3] Groizeleau.

[4] Yves Beigbeder, p. 73.

[5] Denizot.

[6] Captain Delayen (later General Delayen), quoted in Pissardy, p.251.

[7] LeBreton.

[8] Gaudin, Reprinted in Pissardy, p.266.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Colonel Michel Reeb.

[11] LeBreton.

[12] Forum La Guerre d’Indochine.

[13] Bergot, 1997.

[14] Favrel, 1952.

[15] De Pirey, p.159.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Pissardy, p.51.

[18] LeBreton

[19] Reeb

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beigbeder, Yves: Judging War Crimes and Torture: French Justice and International Criminal Tribunals and Commissions, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2006.

Bergot, Erwan: Commando Vandenberghe, Pygmalion, Paris, 1997.

Denizot, Jean-Jacques: L’épopée des trois Capitaines. Jean Claveranne – Henri Morin – Yvan Tommasi. Trois vies, un destin, 2000, https://www.monsieur-legionnaire.org/images/epopee-des-trois-capitaines.pdf

Fall, Bernard: Street Without Joy, Pall Mall Press, London, 1961.

Favrel, Charles: “La Mort d’un Baroudeur,” Le Monde, January 9, 1952, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1952/01/09/la-mort-d-un-baroudeur_1993178_1819218.html

Forum La Guerre d’Indochine: “L’Adjutant-Chef Roger Vandenberghe,” April 9, 2009, https://laguerreenindochine.forumactif.org/t541p1-l-adjudant-chef-roger-vandenberghe

Gaudin, Bernard, Commando 25, Paris, 1990.

Groizeleau, Vincent: “Un ancien du commando François arrive en P-51 sur la BAN d’Hyères,”

Mer et Marine, June 16, 2014, https://www-meretmarine-com.translate.goog/fr/defense/un-ancien-du-commando-francois-arrive-en-p-51-sur-la-ban-d-hyeres?_x_tr_sl=fr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=op,sc

Kennedy, Paul J.: Dinassaut Operations in Indochina: 1946-1954, Unpublished MA Thesis, Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Quantico VA, 2001.

LeBreton, A.: “Commandos Nord Vietnam,” Versailles, July 31, 2007, http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.acuf.fr%2FArticle%2FCommandos%2520Nord%2520Vietnam.htm

Le Morillon, Jean: Un Breton en Indochine, Paris, 2000.

de Pirey, Philippe, Operation Waste, Arco, London, 1954.

Pissardy, Jean-Pierre: Commandos Nord-Vietnam, 1951-1954, Indo Éditions, Paris, 1999.

Reeb, Colonel Michel: “Commando Nord Viet-Nam,” La Charte, December 2003.