Andrew McGregor

AIS Tips and Trends: The African Security Report

June 30, 2015

Earlier this year, Nigeria’s military fortunes brightened suddenly and unexpectedly in the midst of what at first appeared to be a disastrous campaign against the forces of Boko Haram. Though the arrival of new weapons and equipment played a role in this reversal, it now appears that the three-month deployment of South African mercenaries as military trainers and even participants in the fighting in northeastern Nigeria played a major role in enabling Nigeria’s demoralized army to begin expelling Boko Haram militants from their newly occupied territories. While a change in government in Abuja has brought an end to their mission, the evident success of these private military contractors has raised new questions regarding the utility and desirability of using mercenaries in situations where national militaries have failed to make progress against insurgents and terrorists.[1]

Reva Mark III Armored Personnel Carriers operated by South African military contractors in Maiduguri

Lack of political will at the highest levels of President Goodluck Jonathan’s government was largely responsible for the failure of Nigeria’s security services to contain the Boko Haram threat. With the movement seizing new territory and captured arms almost daily, Jonathan suddenly found himself running out of time before the March 2015 presidential election to deal with a file he had done his best to ignore. Something had to be done about Boko Haram quickly, and the president turned to an almost inconceivable solution; the introduction of white and black mercenaries to reverse the fortunes of the Nigerian military, once considered one of the continent’s strongest, but now apparently unable to crush a local rebellion by religious extremists.

While the participation of Nigeria’s Chadian and Nigerien neighbors in a military campaign against the terrorists could be explained by the regional nature of the Boko Haram threat, formally calling on a foreign power to restore order in northeast Nigeria just prior to elections was out of the question. Even if South Africa was considered as a source of military assistance, Jonathan and his aides would have been well aware of the deteriorating state of South Africa’s own military and its less than stellar performance in the Central African Republic in 2013.[2]

Nigerian authorities did not deny the existence of the foreign contractors, but insisted they were only involved in training Nigerian troops in the use of the new weapons arriving for use in the fight against Boko Haram (BBC, March 13, 2015). Most of the mercenaries engaged by Nigeria appear to have been personnel of Specialized Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection (STTEP), a private military company run by Colonel Eeben Barlow, a widely-known private military contractor and former commander of the South African Defense Force’s 32 Battalion. STTEP recruits experienced soldiers by word of mouth, including “reformed” South Africans or Namibians who may have fought against the South African Defense Force (SADF – South Africa’s apartheid-era army) as communist guerrillas during South Africa’s border wars.

Despite statements of sympathy for Nigeria’s predicament, both the U.S. and British governments remained firm in their position that the atrocious human rights record of the Nigerian military during the Jonathan administration precluded a military partnership on the ground or a resupply of armaments.

Shortly after his election, new President Muhammadu Buhari (a retired Nigerian Army major-general who seized power in a 1983 military coup, serving as head-of-state until 1985) expressed his objections to the use of mercenaries in Nigeria (Pretoria News, May 21, 2015). Buhari’s running mate, Yemi Osinbajo (now vice-president) ignored certain military realities in declaring his emphatic opposition to the South Africans’ deployment in Nigeria: “Because of the way that this government has degraded the army, we now find the need to engage mercenaries… There is absolutely no reason at all why the Nigerian army, which is one of the finest armies in the world, now have to engage mercenaries to come and fight” (VOA, March 20, 2015).

Following reports from major human rights organizations of widespread human rights abuses by the Nigerian military in northeast Nigeria, Buhari pledged to bring an end to such violations, promising in his inaugural speech: “We shall improve operational and legal mechanisms so that disciplinary steps are taken against proven human rights violations by the armed forces” (Reuters, June 4, 2015).

Like many of its West African neighbors, Nigeria has prior experience with mercenaries, who were used by both sides in the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970). A large number of Chadian mercenaries and European pilots engaged on the federal side, while a smaller number of Rhodesians and Europeans (mainly British, French, Belgian, Portuguese and German) fought unsuccessfully for Biafran independence.

Who are the Mercenaries?

Most of the South Africans deployed to Nigeria would have served together, black and white, in a select number of South African and South West African military units and paramilitaries of the apartheid era. Others will have served together as private military contractors in the post-apartheid era in organizations such as Executive Outcomes.

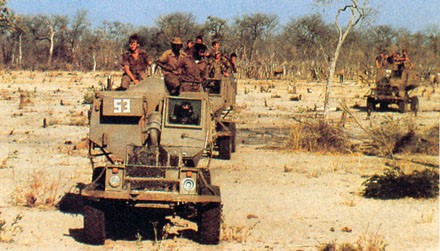

Koevoet Forces on Patrol in South-West Africa (now Namibia) in the 1980s

Koevoet Forces on Patrol in South-West Africa (now Namibia) in the 1980s

Some of the South African contractors are believed to be veterans of Koevoet (“Crowbar”), a white-led, mixed race police paramilitary that operated with great efficiency and brutality in South-West Africa (now Namibia) between 1979 and 1989. Working on a bounty system for killed or captured “terrorists” of the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO), Koevoet scored enormous numbers of kills but took few prisoners. Koevoet bush-craft and tactics were based on the earlier work of the Portuguese Flechas (Arrows) of Angola and Mozambique and Rhodesia’s Selous Scouts. Like these elite formations, Koevet recruited captured fighters who had been “turned,” and occasionally disguised themselves as Marxist guerrillas to carry out ambushes or specific missions.

Other South Africans appear to be veterans of 32 Battalion (a.k.a. the Buffalo Battalion, or “the Terrible Ones”) of the SADF. This white-led unit (recently described by the UK’s Sky News as “a foreign legion of racist mercenaries,” was composed largely of black troops who once belonged to the Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA), an Angolan independence movement that lost a post-independence power struggle with the rival Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA) in 1975. 32 Battalion was deployed largely in southern Angola and played an important part in the series of South African operations in Angola in 1987-1988 against Soviet-led Angolan government forces and their Cuban allies known broadly as the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.

32 Battalion was created and led by Commandant Jan Breytenbach, who was once involved in a covert South African training mission for Biafran rebels in Nigeria.[3] Much hated by South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC), the unit was disbanded in 1993 and its black members retired to the dusty town of Pomfret, where in the absence of other opportunities many continued to seek employment from former SADF officers who had gone on to form private military firms such as Executive Outcomes (EO – 1989-1998) in post-apartheid South Africa. As in their original units, the private military contractors continued to use white officers and senior NCOs, with the other ranks filled largely by black troops.

The “Buffalos” figured in Executive Outcomes operations in Angola and Sierra Leone in the 1990s. Many were unfortunate enough to allow themselves to be recruited by former SAS member and Sandline International co-founder Simon Mann for a failed coup attempt in oil-rich Equatorial Guinea in 2004. Most endured a nasty stretch in prison in Zimbabwe (where they had been arrested en route to Equatorial Guinea) before being returned to Pomfret.[4] A smaller number in the advance party found themselves doing long stretches in Equatorial Guinea’s notorious Black Beach Prison where they were joined by Simon Mann after his extradition from Zimbabwe.

It is likely that some other South Africans may be veterans of the SADF’s Special Forces, known as “the Recces.” These units were once highly active in covert operations throughout southern Africa.

Eastern Europeans were also hired as military contractors by Nigeria and served alongside the South Africans, but their presence does not carry the same political baggage and no complaints have been made. Information about the East Europeans is in short supply, including whether they have remained in Nigeria under separate contract. Ukrainians have become ubiquitous throughout Africa as contracted civil and military pilots of both aircraft and helicopters. Some reports indicate that they have been joined in Nigeria by Russian and Georgian military contractors.

STTEP’s Nigerian Campaign

According to STTEP chairman Eeben Barlow, the military firm was engaged for work in Nigeria as a sub-contractor for an un-named primary contractor in December 2014. Their original mission was to rescue the over 250 schoolgirls from Chibok kidnapped by Boko Haram, though this soon evolved into the creation of a mobile strike force incorporating Nigerian troops capable of reversing Boko Haram’s offensive momentum. The South Africans established a base in a corner of Maiduguri’s airport, closed for the last two years due to instability, but still capable of providing a base for aerial attacks and helicopter missions.

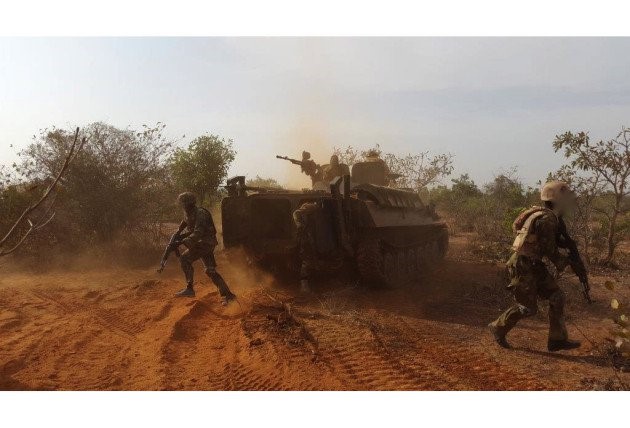

Strike Force 72 Operating in Borno State

Strike Force 72 Operating in Borno State

The STTEP contractors were eventually attached to Nigeria’s elite 72 Strike Force in January 2015 to create a mobile strike force “with its own organic air support, intelligence, communications, logistics and other relevant combat support elements.”[5] After a period of intense training, the strike force conducted its first successful operation in late February. Since then, the South Africans appear to have played a major role in flushing Boko Haram fighters out of their camps hidden in the thick brush of the Sambisa Forest, though some elements remain due to a failure to complete this operation. There is no evidence that either Barlow or the South Africans in the field coordinated in any way with Chadian or Nigerien troops operating in the same region.

Founded in 2006, STTEP International Ltd. describes itself as “an international, privately-owned military, intelligence and law enforcement training and advisory company.” STTEP’s motto is “Failure is never an option,” and the firm claims to have “never failed in any of its missions, undertakings or projects.” The company’s operational procedure is to align itself with the armed forces of the client government to achieve strategic and operational goals through “military input and advice and support at both the operational and tactical levels.” Areas of claimed expertise include counter-terrorism, offensive counter drug operation, unconventional warfare, semi-conventional warfare and covert/clandestine operations.[6]

In all cases, Barlow emphasizes the “African” character of STTEP, a factor he believes improves relations with client nation militaries in Africa and helps training succeed where foreign military missions fail due to “poor training, bad advice, a lack of strategy, vastly different tribal affiliations, ethnicity, religion, languages, cultures [and] not understanding the conflict and enemy.”[7]

Barlow rejects the common media theme that the (mostly black) South Africans working in Nigeria and elsewhere are apartheid-era holdovers:

Some in the media like to refer to us as ‘racists’ or ‘apartheid soldiers’ with little knowledge of our organization… We are primarily white, black, and brown Africans who reside on this continent and are accepted as such by African governments… Had we been the so-called racists some media whores insist on calling us, do you think any African government would even want to speak to us? I very much doubt it.[8]

The Nigerian contract allowed Barlow to demonstrate the virtues of his tactical approach, which he describes as “relentless offensive action.” According to Barlow:

Troops need to develop their aggression level to such a point that the enemy fears them. Aggressive pursuit is aimed at initiating contact as heavily with the enemy as possible.[9]

Using expert trackers, strike force units pursue enemy forces with armored personnel carriers supported by air assets providing fire support, transportation, reconnaissance and medevac. Wherever possible, strike force personnel use helicopters to “leapfrog” the enemy and prevent his escape from pursuing forces. Superiority in night operations, engagement with maximum forces every time the enemy is encountered and the rotation of strike force frontline units enables the strike force to exhaust and confuse the enemy before completing his destruction. Territory retaken by strike force units is then turned over to conventional troops (in this case the Nigerian Army) for consolidation and occupation.[10]

Strike force ground units and their South African trainers relied on South-African made REVA (reliable, effective, versatile and affordable) armored personnel carriers. Capable of carrying ten passengers, the REVA’s V-shaped hull offers mine resistance, while two light machine guns provide firepower. The REVA is considered to be a low maintenance vehicle capable of operating in difficult conditions. Nigeria, Thailand, Yemen and Iraq are among the major export markets for the REVA. According to South Africa’s Netwerk24, twenty of the APCs were sold to Nigeria under a contract approved by the National Conventional Arms Control Committee (Netwerk24, March 11, 2015).

Some of the men who deployed in Nigeria would be known to ex-mercenary pilot Crause Steyl, who played a prominent role in the failed “Wonga Coup.” During the Nigerian deployment, Steyl remarked:

The South African mercenaries are giving Boko Haram a hiding. These guys are in their 50s, but for a pilot or tank driver it doesn’t really matter. There’s going to be no Boko Haram. It boggles the mind that Britain and America promised to help Nigeria but never did. But the South African government doesn’t want [the mercenaries] to exist. They wish them off the planet. When they come back from Nigeria, it will try to prosecute them and put them in jail. Because the colour of these men is white, it makes laws that stop them earning money off shore. How wrong can you be? There is now reverse racism and it’s difficult for white people to get a job (Guardian, April 14, 2015).

Indeed, financial motives appear to inspire these aging warriors more than ideology or racism. Lack of opportunity in the new South Africa is consistently cited by both black and white members of these latter-day mercenary formations and similar motives no doubt lie behind the involvement of the more reticent East European military contractors.

59-year-old Leon Lotz, a former member of Koevoet who was declared persona non grata in Namibia just prior to its independence, was the only South African known to have died by live fire during the deployment. Lotz was killed in a friendly-fire incident that occurred when a Nigerian T-72 tank opened up on a Hilux truck carrying Lotz, an East European (also killed) and a number of black Strike Force members who wer wounded. (VOA, March 20, 2015). Another South African was reported to have died in Nigeria six weeks previously from a heart attack (Netwerk24, March 11, 2015). South Africa’s Defense Ministry used Lotz’s death to issue a warning “to others who are considering engaging in such activities to really think twice and consider the repercussions” (BBC, March 13, 2015).

South African Defense Minister Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula warned that the South African military contractors were in violation of the nation’s Foreign Military Assistance Act and could face prosecution and a possible six-year prison term on their return (Pretoria News, May 21, 2015; The Star [Johannesburg], May 21, 2015). According to the Defense Minister, herself a prominent figure in the revolutionary ANC: “They are mercenaries, whether they are training, skilling the Nigerian defence force, or scouting for them. The point is they have no business to be there” (The Guardian, April 14, 2015). Otherwise, there was a general silence from South African government figures regarding the private military deployment.

Despite their apparent success, STTEP’s contract was not renewed in March, a situation Barlow acknowledges had to do with the change in government, though the STTEP chairman maintains that much of the responsibility lies with the South African print media’s “racist mercenary” narrative: “The South African government has been fed such a false narrative by the South African media that it is possible they requested the Nigerian government not to extend the contract. The media here has tried very hard to turn this into a racial issue with the intent to create as much suspicion as possible.” Nonetheless, Barlow credits the Nigerian Army for driving back Boko Haram, describing “the strike force we trained” as a “force-multiplier in the area of operations.”[11]

To defeat such an enemy militarily, we must out-think and outsmart him by adopting tactics, techniques, and procedures that are so unexpected and unconventional that he becomes confused and loses his cohesion.[12]

Projections

The participation of South African citizens in the campaign against religious extremists in Nigeria is unlikely to have many repercussions within South Africa, where only 1.5% of the population is Muslim (mainly of ethnic-Indian origins) and few of these could be considered radicalized. Nonetheless, there were reports in May of a letter to South African Islamic scholars purportedly from South Africans who have traveled to Iraq (or possibly Syria) to join Islamic State militants. The letter arrived after public criticism of the Islamic State by prominent South African Islamic scholars and warned fellow Muslims:

You are being deceived and misguided by people claiming to have knowledge of what the Caliphate is and what is happening in the Islamic State. Firstly, let us look at the source of this information and knowledge that you are being fed… Most of it is coming from news channels and media sources that are either funded by or run exclusively by Jewish conglomerates. So a large portion of your opinions about your brothers and your state… is based on information that you attain from the enemy (News24 [Cape Town], June 14, 2015).

Several years ago it became commonly thought that the “problem” of South African mercenary activity in Africa was gradually solving itself as the former SADF members who formed the bulk of such groups were simply becoming too old for military adventuring. Though the Nigerian campaign is undoubtedly an unexpected “last hurrah” for many of these ex-SADF soldiers, their apparent success in reversing Boko Haram’s gains in Borno Province could encourage imitation in other African nations unable to deal with insurgencies.

Surprisingly, what the South African episode reveals is that the Nigerian military is entirely capable of dealing with the Boko Haram threat if provided with leadership, training and equipment. The question is whether Nigeria can sustain an offensive led by Special Forces or bog down due to systemic problems within the Nigerian military that cannot be resolved overnight. The recent counter-strikes by Boko Haram militants suggest that the latter result may be the most likely.

In the meantime, private military contractors continue to seek new battlefields while exploiting the apparent legitimization of their trade in Iraq and Afghanistan. In a recent interview, ex-Executive Outcomes director Simon Mann insisted that a 2000 man private military company could, with air and armor support, deal a decisive blow to Islamic State forces in Iraq. Basing his conclusion on the performance of the South-African trained mobile strike force in Nigeria and the success of his own Executive Outcomes combating insurgents in Angola and Sierra Leone, Mann suggests that Islamic State forces “are probably more terrifying than they are competent, and it all comes down to training and experience at the end of the day. We know that the Iraqi army were not being properly led, paid or equipped and that equates to disaster. How did anyone expect it to end? … Don’t get me wrong, [Islamic State forces] are probably very frightening up front, although I doubt they are as professionally trained as the rebels we came up against in Angola (Telegraph, June 4, 2015).

Notes

[1] Without imparting any ethical connotations to the terminology, private military contractors is probably a more accurate term for these modern “mercenaries” in that it reflects the corporate basis of these formations rather than an image of the individual freebooters that once filled mercenary ranks.

[2] See “South African Military Disaster in The Central African Republic: Part One – The Rebel Offensive,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, Washington DC, April 4, 2015, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=238 ; “South African Military Disaster in The Central African Republic: Part Two – The Political and Strategic Fallout,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, April 4, 2015, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=236 ; “The South African National Defense Force – A Military In Free-fall,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, January 25, 2013, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=163

[3] See Piet Nortje, 32 Battalion: The Inside Story of South Africa’s Elite Fighting Unit, Zebra, 2006, pp. 8-9. This history of the unit is written from the perspective of a former regimental sergeant-major.

[4] See Adam Roberts: The Wonga Coup: Guns, Thugs, and a Ruthless Determination to Create Mayhem in an Oil-Rich Corner of Africa, PublicAffairs, 2007.

[5] Jack Murphy, “Eeben Barlow Speaks Out (Pt. 2): Development of a Nigerian Strike Force,” April 6, 2015, http://sofrep.com/40623/eeben-barlow-speaks-pt-2-development-nigerian-strike-force/

[6] See http://www.sttepi.com/default.aspx ; http://www.sttepi.com/major_projects.aspx ; http://www.sttepi.com/special_tasks.aspx

[7] Jack Murphy, “Eeben Barlow Speaks Out (Pt. 1): PMC and Nigerian Strike Force Devastates Boko Haram,” April 1, 2015, http://sofrep.com/40608/eeben-barlow-south-african-pmc-devestates-boko-haram-pt1/

[8] Jack Murphy, “Eeben Barlow Speaks Out (Pt.4): Rejecting the Racial Narrative,” April 8, 2015, http://sofrep.com/40675/eeben-barlow-speaks-pt-4-rejecting-racial-narrative/

[9] Jack Murphy, “Eeben Barlow Speaks Out (Pt. 3): Tactics Used to Destroy Boko Haram,” April 7, 2015, http://sofrep.com/40633/eeben-barlow-speaks-pt-3-tactics-used-destroy-boko-haram/

[10] Ibid

[11] Jack Murphy: “Eeben Barlow Speaks Out (Pt. 6): South African Contractors Withdrawal from Nigeria,” Sofrep, April 17, 2015, http://sofrep.com/40865/eeben-barlow-speaks-pt-6-south-african-contractors-withdrawal-nigeria/

[12] Ibid