Andrew McGregor

February 21, 2007

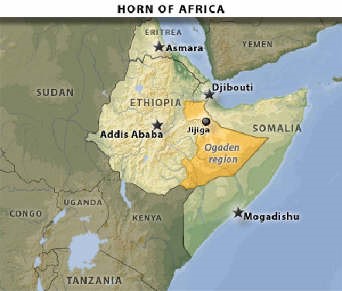

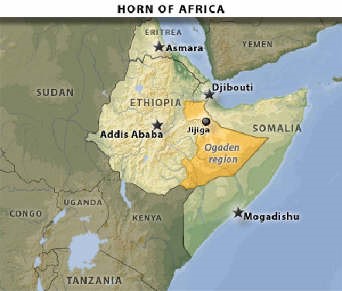

The U.S.-supported Ethiopian invasion of Somalia has an unsettling resemblance to the British-supported Ethiopian incursions in the early years of the 20th century. In both cases, the Western powers became involved because of perceived strategic considerations, while their proxy, Ethiopia, went to war as a result of Somali resistance to Ethiopian domination of the ethnic-Somali Ogaden region. Last December’s invasion succeeded in bringing the Ethiopia-friendly Transitional Federal Government (TFG) of President Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmad to power in Mogadishu. Although the Islamists have been dispersed for the moment, there are signs that a guerrilla campaign is in the making.

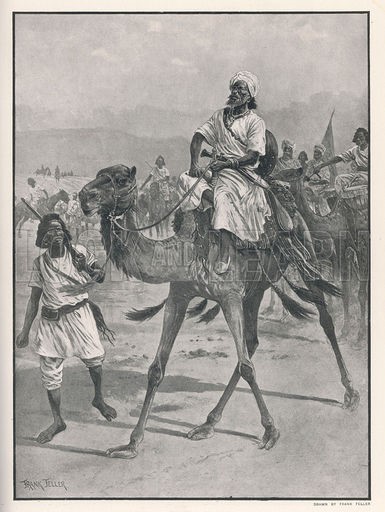

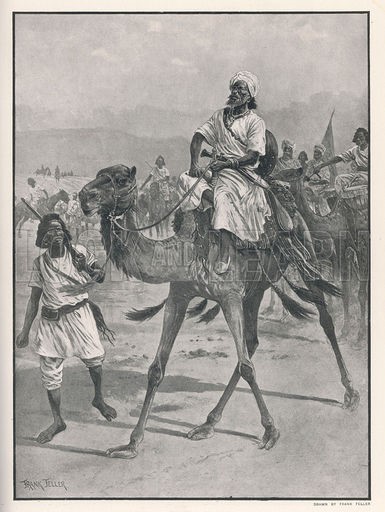

Sayyid Muhammad ‘Abdullah Hassan

Sayyid Muhammad ‘Abdullah Hassan

Like the late 20th century, the late 19th century witnessed an international Islamic revival, spurred in part by the military occupation and economic domination of Muslim nations by the Western world. The Egyptian withdrawal from its short-lived occupation of the Somali coast in the 1880s and the failure of the Ottoman Empire to press its claims on the region opened the region to the advances of Britain, Italy, France and Ethiopia. In Somalia, there was a rare shift in public affairs as religious leaders became involved in traditionally secular Somali politics, using their unique position to transcend traditional clan divisions. The most notable of these leaders was Sayyid Muhammad ‘Abdullah Hassan, who led his “dervishes” in a 21-year struggle against foreign domination.

Introducing Political Islam

As a young man in Mecca, Muhammad adopted the austere teachings of the Salihiya sect of Islam. Like today’s Somali Islamists, Muhammad rejected foreign influence and enforced the strict observance of Islamic law. The uses of alcohol and tobacco were forbidden, as was the use of Qat, a narcotic leaf widely consumed in Somalia. In Somalia’s devastated economy, the Qat trade continues to be one of the most reliable ways for entrepreneurs to make money. The prohibition of the trade by the Islamic Courts Union damaged local support for these modern Islamists only weeks before the Ethiopian invasion (Terrorism Focus, November 28, 2006). Sayyid Muhammad was a harsh critic of Somalia’s dominant (but relatively tolerant) Qadiri Sufi order, who in turn called the renegade holy man “the Mad Mullah,” the name by which he is best known to history.

Like many modern Islamist leaders in Somalia, Muhammad cut his teeth as a political militant in the Ogaden region, preaching resistance to the Christian Ethiopians who were steadily occupying the area. One of Muhammad’s greatest strengths was his mastery of oral poetry, a powerful social and political tool in Somalia, where a man could be ruined by an effective attack in verse or a tribe brought to war by skillful alliteration. At first, the British imperialists who occupied his native northwestern Somalia tolerated Muhammad’s preaching, believing that adherence to Sharia law would help bring order to the wild tribesmen of the interior. It was not long, however, before Muhammad turned his attention to the British because of their support for Ethiopia. By 1899, he had broken with British rule and enraged the Ethiopians with a ferocious but ultimately unsuccessful attack on their forces in the Ogaden. With Britain’s colonial army forced to concentrate on the concurrent war in South Africa, British authorities invited Ethiopia to join the campaign against this troublesome preacher.

Sayyid Muhammad grew concerned that the Ethiopian and Western Christians sought to destroy Islam in Somalia, a fear shared by Somalia’s modern Islamists. In the period 1901-1904, the dervishes repulsed four Anglo-Ethiopian expeditions, although their own losses were often severe. Sayyid Muhammad’s stern and often ruthless measures in dealing with rivals cost him the opportunity of uniting the Somalis against foreign rule.

Somalia’s social structure is also a major obstacle in the development of a unifying Islamist cause. Muhammad never quite succeeded in overcoming the reluctance of Somalia’s many clans and subsections to join a movement that was not directly devoted to enriching or empowering their own group. Military success brought supporters, while failure led to desertions. The problem persists to this day, accounting in large part for the quick collapse of the Islamic Courts Union when an Ethiopian victory became obvious in December.

The Ethiopian and British Campaigns

The first Ethiopian campaign against Muhammad was a disaster. A massive army of 14,000 men chased the dervishes around the near-waterless Ogaden in 1901, its numbers shrinking daily from heat, hunger, thirst and disease. With typical Somali fractiousness, some Ogaden Somalis accompanied the Ethiopian forces against their would-be liberator. To the British authorities, the lesson was obvious, and it was decided in typical colonial fashion that Somalis must fight Somalis. Thousands of tribesmen were recruited under Indian NCOs and British officers to destroy Muhammad’s army. Similarly, the United States engaged Somali warlords under the guise of the “Anti-Terrorist Coalition” to depose of the Islamists last summer. The strategy was a complete failure, with the warlords being driven from most of the country.

A second Ethiopian expedition to the Ogaden in 1903 killed only a few of Muhammad’s men, while suffering terrible losses of their own from lack of food and water. In familiar language, the dervishes were at one point characterized as “terrorist thugs,” and joint British/Ethiopian campaigns continued until the devastating loss of 7,000 dervishes at the 1904 battle of Jidbaale. During these four campaigns, Ethiopian troops were accompanied by British advisers. There are reports that British SAS units are now acting as advisers to Kenyan border forces in an effort to trap fleeing Islamists (Sunday Times, January 14).

After the defeat at Jidbaale, Sayyid Muhammad agreed to settle peacefully in Italian Somaliland, but within months he and his followers were again raiding the Ogaden and British territory in an attempt to drive out the “infidels.” Ethiopia had dropped out of the fighting, leaving Britain to carry on alone. Today, there is a danger of U.S. forces meeting the same fate, as Ethiopia is seeking only a brief occupation and most African Union states (except for Uganda) are very reluctant to commit peacekeepers to a conflict they view as intractable. As Under Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1908, Winston Churchill pointed out the enormous expense involved in holding this deeply impoverished wilderness and the unlikelihood of British-led Indian and Somali troops ever providing security in the interior. Churchill suggested withdrawing to the coast and leaving the barren interior to the dervishes. It was two years before this policy was implemented, but the withdrawal did nothing to end the fighting.

After the defeat at Jidbaale, Sayyid Muhammad agreed to settle peacefully in Italian Somaliland, but within months he and his followers were again raiding the Ogaden and British territory in an attempt to drive out the “infidels.” Ethiopia had dropped out of the fighting, leaving Britain to carry on alone. Today, there is a danger of U.S. forces meeting the same fate, as Ethiopia is seeking only a brief occupation and most African Union states (except for Uganda) are very reluctant to commit peacekeepers to a conflict they view as intractable. As Under Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1908, Winston Churchill pointed out the enormous expense involved in holding this deeply impoverished wilderness and the unlikelihood of British-led Indian and Somali troops ever providing security in the interior. Churchill suggested withdrawing to the coast and leaving the barren interior to the dervishes. It was two years before this policy was implemented, but the withdrawal did nothing to end the fighting.

A strong blow was dealt to Sayyid Muhammad’s movement when two defectors succeeded in obtaining a letter in 1908 from the leader of the Salihiya movement in Mecca condemning Muhammad as a heretic and an infidel. Despite this, Muhammad’s call for an anti-colonial jihad continued to spread and his quick-moving horsemen dominated the desert wilderness. As the First World War broke out in Europe, fierce fighting continued in Somalia, almost unnoticed by the outside world. The conflict continued as Sayyid Muhammad grew older and ever more corpulent, no longer able to perform the feats of horsemanship for which he was once known, but still able to use his poetic oratory to inspire his dervishes. Sayyid Muhammad’s army was finally broken in a combined infantry and Royal Air Force assault on their fortresses in the Somali desert in 1919. Most resistance collapsed with Muhammad’s death from influenza in 1921.

Conclusion

The dervish war with Britain was a direct result of the empire’s cooperation with Ethiopia, which sought to use British support to solidify their rule of the Ogaden region. Although Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi speaks of the importance of joining the “war on terrorism,” it was threats from the modern Somali Islamists that they intended to “liberate” the Ogaden that brought Ethiopia to war. There are signs that Ethiopia is taking advantage of its occupation to round up members of the Oromo and Ogaden rebel movements (Garowe Online, January 13). Others have been intercepted trying to flee into Kenya (Ethiopian News Agency, January 8).

With growing opposition to his government at home and international criticism of his regime’s human rights abuses, Zenawi has strengthened himself by achieving the inviolable status that comes with being a “vital partner” in the U.S. war on terrorism. His power base in the Tigrean-dominated army has improved through U.S. funding, training, intelligence cooperation and the practical (if limited) experience of mobile warfare gained through the invasion of Somalia. The war is also seen as an antidote to recent defections in the officer corps to the Oromo Liberation Front (an Ethiopian resistance movement). The Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) declared on January 7 that “the ONLF will continue to resist the presence of Ethiopian troops in Ogaden and we shall resist the use of our territory as a logistical and planning center for Ethiopian occupation troops in Somalia” (ONLF Statement on Ethiopian Occupation of Somalia, January 7). With political unrest in his own country, Zenawi cannot spare the best units of his army for long.

Despite an al-Qaeda video released on January 4 urging Muslims to go to Somalia to fight the Ethiopians (“the slaves of America”), there is little indication that any have done so. Somalia has always provided an inhospitable environment to foreign adventurers. Popular support for the Islamists was not an expression of approval by Somalis for international terrorism, and Ethiopian/American suggestions that al-Qaeda fugitives had usurped the leadership of the Somali Islamists seem highly unlikely in light of the traditional patterns of Somali power structures.

The United States, like Britain, often tends to regard militant Islam in any form as “fanaticism,” directed by irrational religious impulses. Too frequently, however, foreign intervention is the fuel that allows political Islam to grow in an otherwise hostile environment. TFG Minister of the Interior Hussein Aideed (a former U.S. Marine) provided the Islamists with a rallying point by urging Somali integration with Ethiopia, including the use of a single passport (Shabelle Media Network, January 7). Sharif Hassan Sheikh Adan, the TFG speaker, does not share President Abdulahi’s pro-Ethiopian position, stating “I believe that the security created by the [Islamic] Courts during their six-month rule cannot be recreated by Ethiopian troops, even if they stay in Somalia for another six years” (Garowe Online, January 13).

Despite their desperate position, Somalia’s Islamists remain defiant: “If the world thinks we are dead, they should know we are alive and will continue the jihad against the infidels in our country” (Shabelle Media Network, January 7). Their words are a modern echo of Sayyid Muhammad’s verse: “And I’ll react against the malice and oppression unleashed upon me, Yes, I am justified to smite, to sweep through the land with terror and fury, And I’ll go out to make the country free of infidel influence” (Quoted in Said S. Samatar: Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism, Cambridge, 1982, p.192).

This article first appeared in the February 21, 2007 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

Shaykh Ahmad Shaykh Sharif (Xinhua)

Shaykh Ahmad Shaykh Sharif (Xinhua)