Andrew McGregor

January 30, 2010

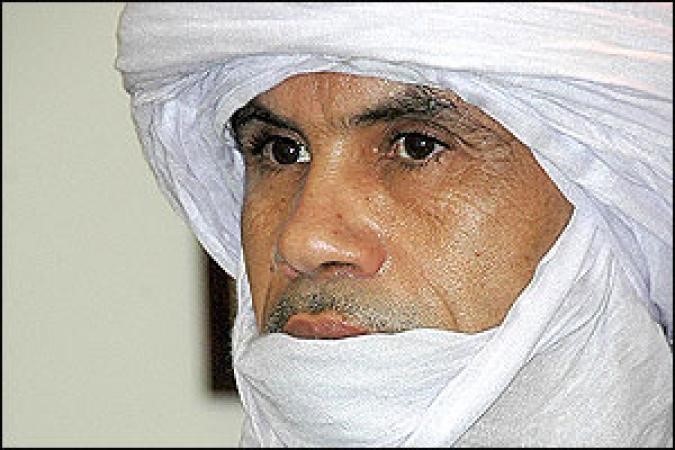

Dr. Khalil Ibrahim Muhammad Achar Foudeil Taha is the chairman of Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (Harakat al-Adl wa’l-Muswaa – JEM), the most powerful and determined of the many armed movements in Darfur challenging the authority of the military/Islamist regime in Khartoum. A former Darfur Minister of Education and member of Hassan al-Turabi’s National Islamic Front (NIF), Khalil enjoys asylum status in France but is often found in the field in Darfur, unlike many of his rivals in Darfur’s other rebel movements. Given the effectiveness of his fighters and the national aspirations of his movement, Khalil Ibrahim is unquestionably the most important of the rebel leaders active in the Sudan.

Khalil specialized in community medicine in the Netherlands while studying at the University of Maastricht and worked as a doctor in Saudi Arabia and Sudan (al-Hayat, December 15, 2009). As a physician leading a military/political movement, Khalil has been ably assisted on the battlefield by a cohort of experienced desert fighters, mostly veteran Zaghawa commanders with experience fighting Libyans in northern Chad.

JEM has its origins in meetings in al-Fashir in the 1990s of a cell of non-Arab members of the National Islamic Front (NIF), led by Dr. Hassan al-Turabi, a veteran Islamist and the architect of Sudan’s Islamic legal system as Attorney General in the government of dictator General Ja’afar al-Numeiri (1969-85). Al-Turabi was determined to bring non-Arab Islamists into the government, but many of those he recruited, like Khalil Ibrahim, were infuriated by the impenetrability of the existing power structure, based on the Ja’aliyin, Shaiqiya and Danaqla riverine Arab tribes (representing less than 5% of the population) that have ruled Sudan since 1956.

The intellectual foundation of the movement is found in a May 2000 manifesto entitled The Black Book: Imbalance of Power and Wealth in the Sudan. Based on extensive statistics, charts and graphs, the work argued that power and wealth in the Sudan had been monopolized by the riverine Arabs since independence. Khalil announced the existence of the JEM shortly afterwards in August 2001. The movement then announced its physical presence in a successful raid on the military airport at al-Fashir in April 2003, carried out jointly with forces of the Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M).

After five years of steady fighting, Khalil’s movement made international headlines with a daring 600 km, 400 vehicle raid on the national capital of Khartoum-Omdurman in May 2008, suddenly transforming the movement from a regional resistance group to a serious threat to the continued existence of the Sudanese regime.. When most of his column was stopped by government resistance in Kordofan, about 75 km west of the capital, a smaller group of JEM vehicles headed straight for the unprepared capital. The attack crested in the suburbs of Omdurman as the remaining JEM vehicles careened through deserted streets until their eventual destruction by ad-hoc units of police and secret service members. Reports at the time that Khalil was in hiding in Omdurman after his truck had been disabled by gunfire led to a government reward of $250,000 for information leading to his capture, but the JEM leader soon resurfaced in Darfur. Khalil regards the attack as a notable success for his movement:

On that day we confirmed to the Sudanese people and the world that our movement has military and political capabilities and has the strong willpower to change the regime in Khartoum. We gained the respect of our people and the world… With our attack on Omdurman, we undermined the regime, which was deceiving the international community that it possessed military power – army, popular defense militias, security services, and the Janjaweed. We confirmed to them that this regime was just a paper tiger” (Asharq al-Awsat, May 13, 2009).

The JEM leader is a member of the Zaghawa Kobe, one of the three main branches of the Zaghawa tribe, which straddles the border between Chad and northern Darfur. The Zaghawa are an indigenous semi-nomadic tribe that maintained their own petty sultanates less than a century ago. Despite small numbers, the Zaghawa now dominate both the government and the opposition in Chad, as well as dominating JEM and several other Darfur resistance groups. JEM’s detractors point to what they allege is the continued domination of the movement’s leadership by the Zaghawa despite its aspirations to be an inclusive organization, but Khalil points to the many Arab and African leaders who have left rival movements for membership in JEM; “The remaining movements should either join us or join the government. There is no third choice in Darfur” (Asharq al-Awsat, May 13, 2009).

Khalil disputes assessments coming from United Nations and United Nations – African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) officials that the conflict in Darfur is dying down, charging instead that such statements are the result of large cash payments made to the officials by al-Bashir’s regime (Asharq al-Awsat, September 26, 2009).

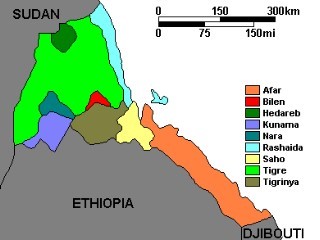

Khalil points to the growing number of political and tribal leaders who have abandoned the regime in favor of JEM as proof of the movement’s appeal beyond Darfur; “The Justice and Equality Movement is a general revolution. It is a revolution for all those who are marginalized and for all the Sudanese people who are demanding freedom, equality, and change. It is not only a revolution for Darfur” (al-Hayat, December 15, 2009). The JEM commander claims the movement also has support in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan (once a stronghold of the Sudanese Peoples Liberation Army – SPLA) and the mountainous region along the Red Sea (another area of discontent with the Khartoum regime). A number of high-ranking Kordofan members of al-Bashir’s ruling National Congress Party defected to JEM in December.

JEM does not recognize the ever-expanding number of “resistance movements” in Darfur, many of which do not carry out military operations against the regime. Khalil suggests many of these groups are creations of Khartoum’s intelligence service. There is some acknowledgement of Abd al-Wahid Muhammad Nur’s largely Fur Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M), but Khalil suggests they have become largely irrelevant by keeping to fortified positions in the Fur heartland of Jabal Marra rather than attacking government positions (al-Hayat, December 15). JEM has carried out a number of military operations in cooperation with the Sudan Liberation Army – Unity (SLA-Unity), one of many SLA/M breakaway groups.

Khalil sees no opportunity for political change in the forthcoming general elections, saying they will be “a complete crisis and a catastrophe”; “[The elections] are a foregone conclusion in favor of the National Congress [Party]. They are a scenario [to extend] Omar al-Bashir’s presidency.” If al-Bashir returns to power, Khalil sees the separation of the South as inevitable, but suggests unity could be preserved if all the Sudanese political parties agreed for Sudan to be ruled by a southern president (al-Hayat, December 15).

Within Darfur, Khalil’s archrival is fellow Zaghawa Minni Arko Minnawi, who took his faction of the Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M) over to the government’s side after the Abuja Accord of 2006. JEM benefited from Minnawi’s decision when many of his fighters began to abandon his movement in favor of continued resistance with JEM; “We are supported by many tribes while Minnawi is surrounded by individuals that are defending his position for which he sold the cause of Darfur. He has become a mercenary while we are fighting for the interests of all of Sudan” (Asharq al-Awsat, September 26, 2009). For his part, Minnawi maintains that JEM “wants to be in control and take charge of other movements. This can never be accepted by a revolutionary movement… The behavior of the Justice and Equality Movement shows that that if they gain power they will annihilate people. The proposals by the Justice and Equality Movement have become Nazi and Fascist-like” (Asharq al-Awsat, September 24, 2009).

In the past, Khalil has accused the Khartoum regime of “an arrogant and patronizing attitude and superficial thinking” and threatened a “second Omdurman,” but with JEM and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) having reached something of a stalemate in Darfur, there are reports that Khalil has entered into direct talks with the Sudanese president’s adviser on Darfur, Dr. Ghazi Salah al-Din, in the Chadian capital of N’Djamena (Asharq al-Awsat, September 26, 2009; May 13, 2009; January 19, 2010). However, there is a deep level of distrust between the two parties and such talks have produced little in the past. While Khalil Ibrahim insists JEM’s preferred strategy is a negotiated settlement with Khartoum that will establish a new and equitable sharing of power and revenues, there is no question he will use JEM’s military strength to press home any advantage that may appear in the political instability that may precede the general elections and the 2011 referendum on Southern independence.

This article first appeared in the January 30, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Militant Leadership Monitor