Andrew McGregor

March 23, 2012

“Underneath the protests after the massacre of Aguelhok, there was a coup d’etat in the making.” In this way, President Amadou Toumani Touré unwittingly predicted his March 21 overthrow by disaffected troops and junior officers during an International Women’s Day speech on March 8 (Info Matin [Bamako], March 9; L’Indicateur du Renouveau, March 9). The move by a group calling itself the Comité national pour le redressement de la démocratie et la restauration de l’État (CNRDR – National Committee for Redressment of Democracy and Restoration of the State) followed weeks of protests by the wives and families of government troops who feared the army was being sent to slaughter without proper arms and equipment. Even before the coup, there were mounting calls for the President to be tried for various offenses, including corruption, patronage, drug trafficking and unenthusiastic pursuit of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) (Mali Demain [Bamako], March 9; Info Matin [Bamako], March 14).

Defense Minister General Sadio Gassama

A Spontaneous Coup?

The coup began at the Sundiata Keita military base in Kati on March 21 during a visit by new Defense Minister General Sadio Gassama and Colonel Abdurahman Ould Meidou, the highly capable leader of a pro-government Arab militia operating in northern Mali. A formal visit descended into an angry confrontation with soldiers as the Minister tried to explain the delay in obtaining new weapons from abroad. When he followed this by an announcement of new troop deployments against the rebels, troops began throwing stones, eventually seizing the base and its weapons before marching on the presidential palace in nearby Bamako (AFP, March 21; Jeune Afrique, March 21).

Though anger had been brewing in the ranks for weeks over the government’s ineffective military strategy, inferior weapons and shortages of food and ammunition in the frontlines, the coup itself appeared to be somewhat spontaneous rather than carefully planned. Typical of the government strategy that has angered the military was the decision to abandon the well-defended Amachah military camp and airstrip at Tessalit on March 10 after a defense of several weeks. The base and town were promptly occupied by the largely Tuareg Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) the next day (L’Aube [Bamako], March 15; AFP, March 12). The “tactical withdrawal” was a severe blow to the morale of the army (Jeune Afrique, March 22). On March 20, a youth march in the garrison town of Kati demanded immediate food shipments to troops in the north and carried banners saying “Liberate Tessalit” (Mali Demain [Bamako[, March 20; Le Republicain, March 20). A shortage of ammunition was one of the key factors in the fall of Aguelhok in January and the subsequent slaughter of much of its garrison (L’Indépendant [Bamako], March 16).

The coup leader, Captain Amadou Sanago, is a virtual unknown in Mali, but claims to have received training from the U.S. Marines and American intelligence services. Sanago claims he does not intend to remain in power, but is vague about when he plans to step down (Reuters, March 23). A junta spokesman, Lieutenant Amadou Konaré, said only that democracy would be restored once “national unity and territorial integrity are re-established” (AFP, March 22). Given the current political conditions in Mali, this could be years in the future.

The Military-Political Response

At the moment, the senior leadership of the armed forces seems to have been caught off guard by this junior officers’ coup, but it is unlikely that figures such as chief of general staff General Gabriel Poudiougou (believed to be in Bamako) and chief of army staff General Kalifa Keita (still at the Firhoun ag Alinsar military base in Gao) will accept this junior officers’ rebellion.

President Touré is also not a vanquished force. At present he is reported to be hidden somewhere near Bamako by loyal members of the “Red Berets,” the President’s personal guard of paratroopers. A former general who first took power in a coup, Touré has an insider’s knowledge of the difficulties of forming a military government and will be ready to exploit any weakness he can identify in the hastily formed junta. There are also reports that a counter-coup is already being planned by loyal officers (Xinhua, March 22). It remains uncertain whether the junta will receive the support of two units that do much of the frontline fighting in the north, Colonel Meidou’s Bérabiche Arab militia and a pro-government Imghad Tuareg militia led by Colonel al-Hajj Gamou, a veteran desert fighter.

As the coup leaders promise to restore democracy while forcing the cancellation of April’s elections the undisciplined men under their command likewise reform the government by the drunken looting of government offices, gas stations and shops. Wheeling around Bamako in stolen cars and firing indiscriminately in the streets has somehow failed to inspire public confidence in the new military leaders of Mali. It is this very group that promises to arrest President Touré by force and try him for unspecified crimes along with various other ministers and government officials already under detention. In the meantime coup leader Captain Sanago apparently does not have enough authority over the mutineers to have them obey his order to cease their looting of the capital.

The putschists in Bamako are certainly swimming against the political tide by imagining their new military government will receive international assistance or recognition. Already the World Bank, the African Development Bank and other donor organizations have suspended all aid to impoverished Mali, putting enormous and immediate pressures on the junta. France, the former colonial power, has made it clear the junta will receive no support from Paris. Many civil and military leaders in Mali are angry with France, believing it to be quietly supporting the Tuareg rebellion. A senior Malian officer recently suggested France cut a deal with MNLA military chief Muhammad ag Najim, promising support for an independent Azawad if Tuareg troops and officers would abandon Mu’ammar Qaddafi (Jeune Afrique, March 13). Such perceptions were likely influential in Bamako’s decision against allowing the French to build a military base at Mopti devoted to counterterrorism operations. African Union Commission chief Jean Ping was particularly scathing in his assessment of the coup: “”This rebellion has no justification whatsoever, more so given the existence, in Mali, of democratic institutions which provide a framework for free expression and for addressing any legitimate claims” (AFP, March 22). The African Union charter calls for the suspension of any member nation whose government has been taken over by force.

Iyad ag Ghali

Ansar al-Din’s Islamist Revolution

The MNLA’s Salafist partners in the Ansar al-Din movement do not seem to be getting much play on the jihadi websites, a sign the movement does not fit within the larger global Salafi-Jihadi trend. The movement’s Tuareg leader, Iyad ag Ghali, has little history of being a follower, and will likely take the movement in distinct directions determined only by himself and a small cadre of advisers. Ag Ghali is apparently more interested in implementing Shari’a in northern Mali than in establishing the independence of the new state of Azawad proposed by the MNLA. The coup could hardly come at a worse time for government efforts to suppress the northern rebellion, as reports begin to circulate of divisions between the secular MNLA and the Salafist Ansar al-Din movement (L’Indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], March 21). A recent three-day meeting between leaders of the two movements failed to resolve their differences (Info Matin [Bamako], March 21).

The MNLA reportedly tried to shift Ag Ghali away from his intention of creating a Shari’a state in northern Mali, but issued the following statement dissociating itself from ag Ghali’s Ansar al-Din after their efforts were rejected: “The republic for which we are fighting is based on the principles of democracy and secularity. There could be possible confusion between our fight and that of a group which aims at instituting a theocratic regime” (L’Informateur [Bamako], March 21). Instead of moving to exploit the split in the rebel alliance, the military is now consumed by its own split, which has also put into question Mali’s continuing role as a partner in regional counterterrorism efforts. Military cooperation with the Bamako junta would seem to be out of the question and the future of the American military training mission in Mali is uncertain. This year’s Operation Flintlock, the ongoing U.S. organized Afro-European counterterrorism exercise was already cancelled because of the unrest in northern Mali.

Regional Implications

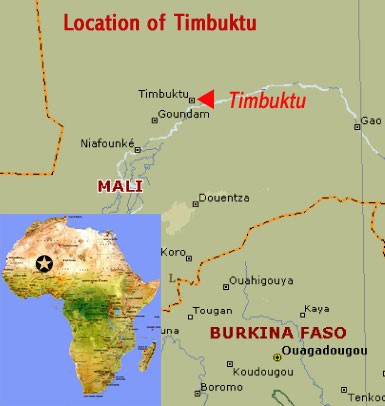

Algeria and Mauritania have long been critical of Bamako’s sluggish military response to the creation of AQIM bases in northern Mali, with Mauritania feeling increasingly free to carry out its own military operations in Mali if the local government is unwilling to do so. On March 11, the Mauritanian Air Force struck a vehicle carrying two Timbuktu merchants, wounding them severely, apparently in the mistaken belief that the vehicle contained AQIM operatives (L’Indépendant [Bamako], March 14; L’Aube [Bamako], March 15; Le Republicain [Bamako], March 14). Like the other nations in the region under pressure from AQIM activities, they are highly alarmed by what appears to be a strategic disaster in the making.

Nearly 200,000 refugees have poured out of Mali in the last two months, seeking food, shelter and refuge in neighboring nations suffering from drought and shortages. There are signs, however, that the rebellion in northern Mali may follow them; Aghaly Alambo, a former Tuareg rebel leader and recent commander in the Libyan military, was arrested in Niger on March 20 in connection with an intercepted shipment of over 1,300 pounds of explosives (RFI, March 21; Reuters, March 21).

Conclusion

The mutiny and coup will do nothing to further the fight against Tuareg rebels; on the contrary, the collapse of the military command in the north has led to military units there falling back on the northern city of Gao, unsure of what to do next. Gao, a city of only roughly 86,000 people, is now struggling to support some 18,000 refugees from the countryside (Jeune Afrique, March 22). The MNLA has already announced its plans to use this opportunity to advance on the other disorganized and demoralized garrisons of Gao, Kidal and Timbucktu (VOA, March 23). The mutiny appears to have spread to the garrison in Gao, which arrested their senior officers and began firing wildly in support of the coup, a perhaps unwise method of showing support in a city that may soon be under siege considering lack of ammunition is one of the mutineers’ main complaints (AFP, March 22).

A further ominous sign is the resurrection of the notorious Ganda Iso militia, a loosely organized and largely undisciplined militia formed largely from the black African Songhai and Fulani communities of northern Mali, a development that threatens the outbreak of a squalid ethnic and racial conflict of atrocities and counter-atrocities.

Ongoing efforts to persuade Mall’s military partners of the need for new weapons to counter the revolt in the north will now come to naught, as it is unlikely any nation will provide Mali’s new military regime with weaponry. The only hope now is that the leaders of this relatively unplanned coup with little ideology beyond obtaining better weapons and ammunition will prove susceptible to international pressure as they come to realize the complexity of running a modern state.

The coup has created excellent conditions for al-Qaeda to entrench itself in Mali with minimal interference and is probably the greatest gift possible for those seeking to create the new nation of Azawad. Unless the internal collapse within the armed forces can quickly be reversed, both AQIM and the MNLA will score what may prove to be irreversible gains against a state rendered largely defenseless by its own military.

This article first appeared as a Jamestown Foundation “Hot Issues” Special Commentary, March 23, 2012.

Mali-Mauritania (BBC)

Mali-Mauritania (BBC)