Andrew McGregor

May 27, 2011

“The bravest men can do nothing without guns, the guns can do nothing without plenty of ammunition, and neither guns nor ammunition are of much use in mobile warfare unless there are vehicles with sufficient petrol to haul them around.” General Erwin Rommel, 1942 [1]

In mid-November, 1942, General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps ran out of fuel in the midst of the battle for eastern Libya. An Italian naval convoy carrying fuel to Benghazi turned back rather than risk entry into the harbor. Though sporadic fuel supplies continued to arrive by air and sea, it was not enough, and the once feared but now isolated Afrika Korps entered a swift decline, eventually surrendering to Allied forces in May 1943.

The Afrika Korps in Libya: No Fuel, No Victory

The Afrika Korps in Libya: No Fuel, No Victory

Unlike Rommel, however, Libyan leader Mu’ammar Qaddafi does not need to seize and hold territory in the desert, thus eliminating worries about extended supply lines. Occasional raids by small mobile groups are sufficient to prevent the rebels of Benghazi from making new shipments of oil that will fund their revolt. If the Libyan revolution must be funded entirely out of the pockets of Western taxpayers, it will become increasingly hard to sell in countries such as the UK where substantial cuts are being made in all sectors of government, including the military. Such raids may also dry up fuel supplies for the lone rebel-held refinery, which in turn will be unable to supply the gasoline-powered turbines that run Benghazi’s energy plant. So long as the regime can operate with a free hand in the desert, time is clearly on Qaddafi’s side in this conflict.

Perhaps conscious of this, the NATO bombing campaign seems to have taken on a new tone of urgency, with strikes on Qaddafi’s Bab al-Zawiya compound in Tripoli designed to eliminate the leadership in hopes of bringing a swift end to the conflict. The arrival, off the Libyan coast, of the French amphibious assault vessel Le Tonnerre with 16 military helicopters may also mark a new phase in NATO efforts to bring the war to an end (Le Figaro, May 22).

Of course, this still leaves the vast majority of Libyans who, even if they oppose Qaddafi, have no wish to be ruled by the Benghazi–based clique that a few Western countries have already recognized as the legitimate government of Libya.

Changing Tactics and Strategies

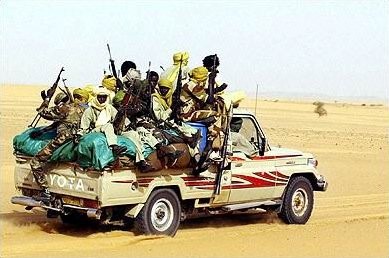

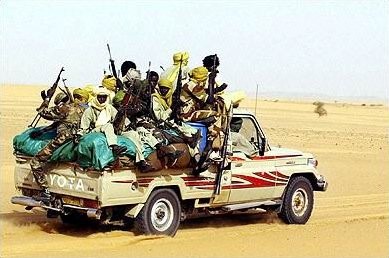

In one way, the imposition of a no-fly zone actually helped the Libyan regime by forcing it to abandon fuel-consuming armor and aircraft in favor of lighter and highly mobile vehicles that use far less fuel and are difficult to identify from the air. Though Qaddafi began the war as a modern “Rommel,” reliant on conventional armor-based forces, he has been forced to adopt the methods of the long-range desert raiders of World War II, a proven formula in desert warfare. In this, his commanders may be able to apply the bitterly-learned lessons of the 1987 “Toyota War” in Chad, where, like the Italians before him, Qaddafi’s heavy forces were rolled up by highly mobile and lightly armed fighters striking out of the desert on light trucks.

The defeat of Rommel took place at sea as well as on land, with Allied ships and aircraft intercepting an increasingly larger proportion of the fuel tankers sent to resupply his petrol-thirsty army. As Rommel noted: “In attacking our petrol transport, the British were able to hit us in a part of our machine on whose proper functioning the whole of the rest depended.” [2] Qaddafi continues to receive fuel from Italy and elsewhere, shipped through third parties in Tunisia (Guardian, May 5; The Peninsula, May 21). Unless this flow can be cut off, it will continue to be difficult to bring the regime’s mobile forces to a standstill.

The Evolution of Motorized Warfare in the Libyan Desert

The idea of creating small, mobile attack and reconnaissance groups using specially modified vehicles was devised by Major Ralph Bagnold, one of a number of British officers stationed in prewar Egypt and Sudan, who used their off-duty time to explore the vast Libyan Desert in stripped-down civilian vehicles. [3] Bagnold and his colleagues trained a small but disparate group of volunteers from New Zealand, Rhodesia and various British Guards and Yeomanry regiments in the techniques of desert driving, navigation and warfare as part of the newly formed Long Range Desert Group (LRDG). [4] Besides providing invaluable intelligence, the LRDG mounted raids in conjunction with the Special Air Service (SAS) designed to destroy enemy airfields and petrol dumps, occasionally fighting battles with their Italian counterparts in La Compania Sahariana de Cufra.

In 1941, the LRDG joined Free French forces, including Senegalese and Chadian (Tubu and Sarra) colonial troops under General Leclerc, in a daring 850 km raid from the Chadian oasis of Faya Largeau on the strategically located Kufra Oasis in southwest Libya. The Italians had thought such a raid impossible, and the loss of Kufra and its airfield was at once both a crippling blow to Italian communications with its East African empire and a resounding demonstration of the abilities of motorized attack forces in desert warfare. Lessons learned here were later applied in the “Toyota War” of 1987, in which largely Tubu forces under Hissène Habré (with French logistical support and the covert assistance of French Foreign Legion units) drove the Libyan army out of northern Chad, seizing the Libyan’s main base at Faya Largeau, despite being outnumbered and outgunned.

Highly Mobile Chadian Troops Consistently Outflanked Stronger Libyan Forces in the “Toyota War”

Highly Mobile Chadian Troops Consistently Outflanked Stronger Libyan Forces in the “Toyota War”

Since that time, Kufra’s strategic importance has actually grown as it provides a controlling position over the vast oilfields of eastern Libya, and is a vital point on the Libyan-built desert road system connecting Libya to Chad and Darfur. In late April, a column of roughly 250 Libyan loyalist fighters crossed nearly 1,000 km of desert from Sabha to Kufra, taking the oasis after a brief firefight with rebel forces there. [5] So long as Kufra remains in loyalist hands, there is little chance of the rebels restarting oil operations in eastern Libya.

Desert Raids May Cripple the Rebel Cause

Desert raids have enabled Qaddafi to cripple the long-term prospects of the rebellion quickly, decisively and at little expense. Operating out of the Waha oil field or the military base at Sabha Oasis (home of loyalist Magraha tribesmen), Qaddafi’s raiders carried out a series of long-range operations in early April that struck the Misla and Sarir oil fields, targeting storage tanks and pipeline pumps. [6] The targeting appears to have been carefully calculated; the damage could be easily repaired under normal conditions, but the skilled workers in the oil fields have been evacuated leaving no-one to make repairs.

The rebels do not have the manpower to defend infrastructure and pipelines stretched over hundreds of miles of desert, so in this way Qaddafi has brought rebel oil production to a halt without causing permanent damage to facilities he would like to retain and return to production in the event of a victory or negotiated settlement. Should these prospects dim in the coming months (or years), more permanent damage can be easily inflicted. Aware of their inability to protect the oil fields, the rebel leadership has demanded that NATO do it for them, a task not easily done from the air. With the sanctions in force against government oil sales, Qaddafi’s greatest advantage is that he does not need to hold the oil fields or even conduct regular raids—the mere threat of such operations is enough to keep the oil fields inoperative.

The raids have prompted an announcement by the rebel-operated Arab Gulf Oil Co. (AGOCO) that oil production will not resume until the war is over. According to AGOCO information director Abdeljalil Muhammad Mayuf: “Everything depends on security. We can produce tomorrow, but our fields would be attacked. We cannot put an army around each field. We are not a military company and the forces of Qaddafi are everywhere” (AP, May 15).

For now, the lone rebel-held refinery in Tobruk is receiving only the oil that was already in the pipeline before the attacks as it slowly trickles through by gravity, the booster system that normally pumps oil through the pipeline having been badly damaged in an April 21 raid by loyalist forces. The oil inside Tobruk’s storage tanks is not available for export, being needed to power desalinization plants and Benghazi’s diesel-fuelled hydro-electric plant, which is now running at three-quarters capacity to save fuel. This supply is expected to last only a few months before, in true “coal to Newcastle” fashion, the rebels will need to start importing oil as well as the gasoline imports it already relies on (Reuters, April 23; NPR, May 15). Benghazi’s energy plant used to be run by natural gas from Marsaal-Burayqah (a.k.a. Brega), but this city is now in loyalist hands. Keeping the desalinization plants running is crucial in case Qaddafi cuts fresh water supplies from the “Great Man-Made River” project, which taps extensive reserves deep under the Libyan Desert. If that were to happen and the desalinization plants fail, rebel-held territory would also depend on foreign shipments of fresh-water to survive.

Both Sides Face Petrol Shortages

The rebels’ lone sale of oil was expected to bring in $129 million, but $75 million of this total was needed immediately to pay for a single shipment of gasoline (Reuters, April 23). Yet, instead of rationing precious gasoline supplies, the rebel administration has actually lowered the already low subsidized price, encouraging young men to use the scarce fuel to race their vehicles in pointless displays of bravado better saved for the frontlines (NPR, May 15). The Tripoli government, by comparison, is being far more careful in its distribution of gasoline, even at the risk of inflaming the public. Supplies available to civilians are short, as are tempers at fuel stations that can have waits of several days. Libya’s own refining capacity has always been limited, though efforts are underway to increase capacity at government-held refineries at Ras Lanuf and Zawiya (Guardian, May 5).

Residents of Tripoli recently attacked a bus carrying foreign journalists with knives and guns—such buses are given priority at petrol stations (Reuters, May 22). Fuel purchases are being further complicated by a growing shortage of currency on both sides of the conflict as consumers hoard cash and banks limit withdrawals—a major shipment of new British-made bills is being held up by sanctions, though its military use is disputable. In terms of real funds, however, Qaddafi is well supplied with foreign reserves (estimated at $100 billion, much of it beyond the reach of sanctions) and a large store of gold that continues to appreciate, due, in part, to the instability in Libya.

NATO has begun interdicting fuel shipments to government-held ports in Libya under the “all necessary measures” clause of UN Security Council Resolution 1973, designed to prevent the killing of civilians by the Libyan regime. On May 19, NATO forces boarded the Jupiter, a tanker carrying 12,750 tonnes of gasoline from Italy in Libyan waters, ordering it to anchor off Malta. Another vessel, the Cartagena, was reported to be on its way to Zawiyah with a load of 42,000 tons of fuel from Turkey (Petroleum Economist, May 19). The rebel Transitional National Council (TNC) has asked NATO to prevent all fuel shipments from reaching government ports, but stopping tankers in Libyan or international waters is of questionable legality under international law.

Conclusion

Of course, there is no guarantee that the mercurial Libyan leader will take advantage of the opportunities now presented to him. Yet, those supporting the Benghazi rebels should be aware that the initiative still lies with Qaddafi should he choose to shift his efforts from the now static coastal campaign and exploit the desert option. While the rebels consist largely of urbanized Arabs from towns and cities along the Mediterranean coast, Qaddafi may call on experienced desert fighters from the nomadic Arabs of the interior as well as fighters from the Tuareg and Tubu groups, long recognized as established masters of the desert. [7] NATO currently faces a shortage of refueling and long-range surveillance aircraft in the Libyan deployment that would help secure the vast Libyan interior. Rebel planning to deal with difficulties in the south is complicated by internal divisions within the rebel leadership, a lack of trained men and the general reluctance of defecting troops to participate in frontline operations. In this environment, Rommel’s observations on the importance of petrol as a decisive factor in campaigning in the Libyan Desert are as relevant today as they were in 1942.

Notes

1. Erwin Rommel (ed. by Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart): The Rommel Papers, 15th ed., New York, 1953, p.359.

2. Ibid, p. 328.

3. See Andrew McGregor, Jamestown Foundation Special Commentary on Libya: “It Didn’t Start This Way, but it’s a War for Oil Now,” April 20, 2011.

4. An excellent account of the Guards units in the LRDG can be found in Michael Crichton-Stuart, G Patrol, London, 1958.

5. See Andrew McGregor, “Qaddafi Loyalists Retake Strategic Oasis of Kufra,” Terrorism Monitor Brief, May 5, 2011.

6. See Ralph A. Bagnold, Libyan Sands: Travel in a Dead World, London, 1935.

7. The Tubu of southeastern Libya and northern Chad have a fearsome reputation as desert warriors. According to Bagnold: “For many years, perhaps for centuries, raids had been made by the black Tubu hillmen of the western highlands into nearly every region bordering on the South Libyan Desert. Their movements were unknown. They operated in places as far apart as the Nile Valley and French Equatoria, Darfur and the oases on the Arba’in Road. How they operated across such vast distances of desert no one could tell. The raiding parties were small and extraordinarily mobile; their seeming indifference to water supplies undoubtedly stimulated the general belief in the existence of undiscovered wells away out in the desert.” Libyan Sands, pp. 238-239.

This article first appeared in the May 27, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor