By Andrew McGregor

February 7, 2008

After the recent admission by some of Turkey’s leading former military commanders that the military option was not the best or only way of resolving Turkey’s Kurdish problem, it is now becoming clear that the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) is taking a new direction—looking for a solution in Islam. Ottoman nostalgia is an important element in the AKP’s approach, which hearkens back to a time when Turks and Kurds were united under Islam and the caliphate. In turning to Islam, the AKP is entering into a three-way struggle to mobilize Kurdish Islam for political ends following years of insurgency and terrorism led by the radical secular nationalists of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Revising their approach, the PKK is now beginning to vie for the support of southeastern Turkey’s conservative Kurdish community. This support is also sought for other purposes by more shadowy groups like the Turkish Hezbollah and even Turkey’s far-right “deep state” extremists.

Elections Approach

With the entry of the Kurdish Democratic Society Party (DTP) into mainstream Turkish politics, there was initially some speculation that this would mark the beginning of a political solution to the Kurdish problem. In practice, the AKP has decided not so much to pull the Kurdish DTP into Turkish politics as to eliminate it through legal and political means. The AKP envisions becoming the representative party of a new Islamic Kurdistan, creating social ties through charitable Islamic NGOs that will eventually lead to the development of a new political power-base for the AKP in southeastern Turkey. With regional elections approaching next year, the AKP is determined to increase the surprising strength the party showed in the region during the last elections.

AKP rule has benefited the Kurdish middle class through investment initiatives while the Gülen movement and other NGOs have stepped in to provide assistance to the lower classes of Kurdish society. The DTP accuses the AKP and other Islamic organizations of using charity to wean Kurdish voters from the DTP (Today’s Zaman, December 31, 2007). With the DTP still tightly tied to imprisoned PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan, the PKK’s continuing series of terrorist bombings is alienating Kurdish voters who might otherwise support the DTP.

In a recent interview with two aides of PKK military leader Murat Karayılan, the PKK officials admit that the AKP’s popular stand on removing the ban on Islamic headscarves for women poses a serious threat to Kurdish support for the PKK and DTP. PKK enthusiasm for an armed solution to the conflict appears to be waning (Sabah, February 5). A boost in social welfare in southeastern Turkey is directed at the poorer classes of Kurds who have traditionally supplied the manpower for local insurgencies.

The Shaykh Said Revolt of 1925

In the early post-war days of the Turkish Republic, Kurdish nationalists quickly realized they did not have the necessary support to mobilize the masses as part of their aim of achieving independence for Kurdistan. A number of present and former military officers formed the secret Azadi (Freedom) group with the intent of providing military support for a revolt to be led by religious figures capable of rousing such mass support, but the organization was broken up by Turkish security forces in 1924.

The 1920 Treaty of Sèvres had promised the creation of a new Kurdish state from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, but Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s rejection of the treaty brought the nationalist project to an abrupt halt. The conservative and largely rural Kurds opposed Mustafa Kemal’s secular reforms and the abolition of the sultanate and caliphate in the early 1920s. The caliphate was the strongest bond between the Turkish and Kurdish communities in Turkey and its elimination was deeply opposed by the Kurds, who had turned out in great numbers in response to the Sultan/Caliph’s call for jihad during the First World War. As traditional religious schools were replaced by modern Western-style academies, Kurdish anger grew and both nationalists and religious leaders saw an opportunity.

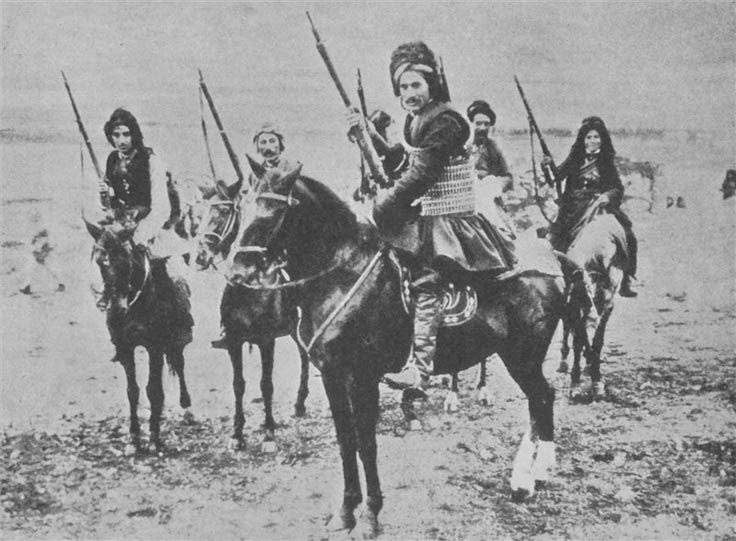

The eventual rebellion, led by the Kurdish Sufi, Shaykh Said Piran, lasted only a brief two months in 1925, but marked a turning point in Kurdish-Turkish relations. This peasants’ revolt was centered in the mountains north of Diyarbakır. Only Sunni Kurds participated—the Alevi Kurds, who practice a mix of Shi’ism and Bektashi Sufism, initially favored the secular reforms as a means of freeing themselves from periodic repression by the Sunni majority. Said was sympathetic to the aims of the nationalists, but these views were not shared by his fellow shaykhs. Naqshabandi Sufi shaykhs provided the core leadership of the revolt. Though many of these had military experience during WWI, the military skills of the imprisoned Azadi veterans were still sorely missed. A Qadiri Sufi, Shaykh Mahmud, had already tried and failed to lead a rebellion only a short time earlier and a revolt by the Alevi Kurds—the Koçkiri Rebellion—had been suppressed in 1920.

Shaykh Said roused the rural population by maintaining that Islam was under attack, urging the restoration of the caliphate while using the language of martyrdom and jihad. Columns of peasants marched into towns carrying green flags and Qurans, meeting little opposition from the mostly Kurdish gendarmerie. Small detachments of regular infantry and cavalry were swept aside, with a number of artillery pieces falling into Kurdish hands. The rebellion reached its crest when 10,000 rebels besieged the walled city of Diyarbakır. Unable to take the city from its resolute commander, Mursel Pasha, the rebels began to realize the intervention of their revered shaykhs was not going to be enough to topple the Turkish state.

The inevitable government counter-offensive began in late March, with attacking planes of the Turkish Air Force driving panicked Kurds into the mountains, where they were destroyed by Turkish infantry. Shaykh Said and 47 others were executed in September 1925.

Following the rebellion, all Sufi orders in Turkey were abolished by order of Atatürk, with many of the Kurdish Naqshabandi shaykhs crossing into the Kurdish region of Syria, where their descendants remain active today. The dervish orders were abolished because of their ability to organize clandestine political networks. The authority of the shaykhs allowed them to cross tribal lines in their organizing efforts. Sufi meeting halls which had once been a refuge from police surveillance were permanently shut down after the revolt.

New powers were assumed by the state in the wake of the rebellion, setting back Turkey’s democratic development. Existing restrictions on the expression of Kurdish culture and language were invigorated and expanded. Kurdish identity was denied in favor of ethno/cultural assimilation. Rebellions continued under this regime, including one led by Shaykh Said’s brother, Shaykh Abdurrahman, in 1927.

Gülen Movement

At the heart of the AKP’s Islamic offensive in southeastern Turkey is the enigmatic figure of Fethullah Gülen, whose self-named Islamic movement is generally regarded as an offshoot of Naqshabandi Sufism. Despite being charged with conspiring against the Turkish republic in 1999—and eventually acquitted in 2006—Gülen has used the generous donations of his followers to build an international network of Islamic schools and NGOs. Though he has been a resident of the United States since 1999, Gülen is believed to have close ties to the highest echelons of the ruling AKP, many of whom also have connections to the Naqshabandi Sufis.

Gülen is a follower of the teachings of Kurdish philosopher and religious scholar Said al-Nursi (1876-1960), formerly known as Said al-Kurdi. As a Naqshabandi Sufi in the 1920s he declined to participate in Shaykh Said’s rebellion on the grounds that the Turkish nation had been at the service of Islam for 1,000 years. Although al-Nursi preached Islamic unity regardless of national borders, there have been efforts recently from Kurdish opponents of Gülen to emphasize al-Nursi’s Kurdish identity over Gülen’s alleged “pan-Turkism” (KurdishMedia.com, January 20).

Today Gülenists, some of whom fly in from Istanbul, distribute food to the poor, manage schools and provide much-needed medical services in southeastern Turkey. Since 1994 the Gülen movement has even opened eight schools in Kurdish northern Iraq where their opponents have accused them of spreading “Turkish racist ideology.” The schools are nevertheless very popular with the families of Kurdish bureaucrats and politicians (Turkish Daily News, December 26, 2007). Other Islamic NGOs are active in southeastern Turkey, including Mustazaf-Dar, believed to have ties to the Turkish Hezbollah (Today’s Zaman, December 31, 2007).

Kurdish Islam and the “Deep State”

There also appears to have been interest in Kurdish Islam from a more nefarious source, the Turkish “deep state” apparatus known as Ergenekon, members of which were recently rounded up by Turkish security forces (see Terrorism Monitor, February 7). Ergenekon grew out of NATO’s Operation Gladio, a secret Cold War formation of military and security personnel designed to offer prolonged resistance in the event of being overrun by Soviet forces. In Turkey the Gladio operation survived the Cold War by establishing deep roots in various political, military, security and criminal organizations. At the same time, the group began to assume guardianship of an ideal and rigidly Kemalist Turkish nation.

Following the arrests in late January there were reports that Ergenekon had held talks with the PKK and Dev-Sol (the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front) in Germany and had even started organizing a Kurdish Islamist terrorist group as part of their plan to spread chaos in Turkey prior to a military coup scheduled for 2009 (Yeni Safak, February 2; Istanbul Star, January 28). Another report claimed that the gang had recruited members of the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons—a PKK offshoot—to blow up a bridge near the headquarters of the Turkish air force and navy (Hürriyet, January 29). The fourth stage of Ergenekon’s plan to create conditions designed to enable a military coup is also said to have called for the creation of sham terrorist groups whose activities would spark conflict between Turks and Kurds (Zaman, January 28).

The Turkish Hezbollah

A January 25 report in the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet claimed that some of the Ergenekon agents were formerly active members of Turkish Hezbollah. For some years now rumors have circulated in Turkey charging that Turkish Hezbollah was the creation of the Gendarmerie Intelligence Group Command (JITEM), a secret and officially denied agency formerly led by prime Ergenekon suspect, retired Brigadier General Veli Küçük.

The Hezbollah were recently described as “predominantly and passionately Kurdish and can be seen as virtually the linear descendants of the participants in the failed Shaykh Said revolt of 1925…” [1]. While ostensibly seeking the establishment of an Islamic state, the Turkish Hezbollah has actually had more in common with Turkey’s right-wing extremists than with other Islamist movements. Its membership is largely Kurdish but in general the organization has few ties to the community. The movement was engaged for years in a brutal and bloody struggle with the PKK with little interference from authorities. Hezbollah denounces the PKK as anti-Muslim Marxist-Leninists who collaborate with anti-Turkish Armenians.

In January 2000, Turkish police rounded up 2,000 Hezbollah members and killed its leader, Hüseyin Velioglu. After evidence emerged of the movement’s predilection for brutal murders and torture, the group became popularly known as Hizbul Vaset (The Party of Slaughter). Though much diminished in strength, Hezbollah operatives still pose a serious threat to security, particularly through ties to organizations like Ergenekon.

Conclusion

The failure of religious-led revolts—of which the Shaykh Said rebellion was but the largest—caused the later Kurdish nationalists to look for new revolutionary models, eventually finding one in secular Marxism. The PKK turned its back on the example of these early “reactionary” tribal and religious leaders in favor of pursuing an independent socialist state free of the tribalism that constantly foiled all attempts to unify the Kurdish people in a single nation. The PKK has nevertheless had to adjust to the Islamic renewal in their home region, moderating their once-strident Marxism through the founding of the Kurdish Prayer Leaders’ Association. The PKK now professes respect for all Kurdish religious practices, including Shi’ism, Yezidism and Zoroastrianism (Today’s Zaman, December 31, 2007).

The Naqshabandi movement is active once more in southeastern Turkey, with a lodge in the city of Adıyaman and frequent visits from the shaykhs of the Naqshabandi lodges in Kurdish Syria. The Sufi movements still display remarkable organizational skill; in Iraq this has been applied to a military anti-occupation campaign (see Terrorism Focus, January 8; Terrorism Monitor, January 24).

Instead of driving the Kurds away with secularism as they did in the 1920s, the new approach of the AKP now tries to entice the Kurds away from secularism with Islam. If language and ethnicity are insurmountable barriers, then Islam will be the bridge between communities. In combination with a robust military campaign by the Turkish armed forces against PKK bases in northern Iraq, Turkey’s Islamic initiatives in its Kurdish regions are sapping strength from a radical form of secular Kurdish nationalism that appears to be on the defensive and without allies. The problem is whether the military phase of Ankara’s campaign will ultimately prove counterproductive if Turkish Kurds begin to rally around the PKK simply because they are fellow Kurds (see Eurasia Daily Monitor, January 28). Turkey’s strong secular establishment is also certain to express their opposition to the growing “Islamification” of southeastern Turkey.

Notes

1. Emrullah Uslu: “From Local Hizbollah to Global Terror: Militant Islam in Turkey,” Middle East Policy 14(1), Spring 2007