Andrew McGregor

August 10, 2007

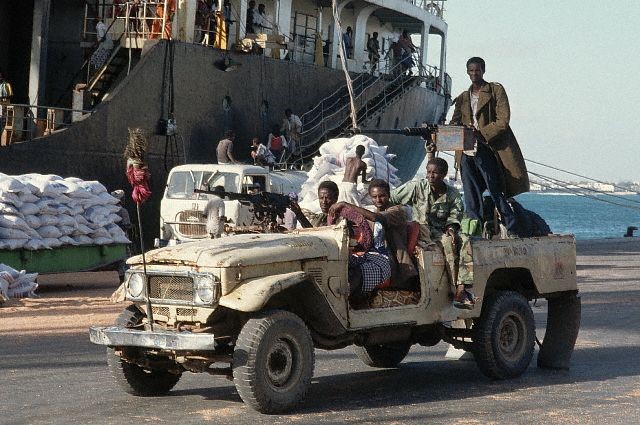

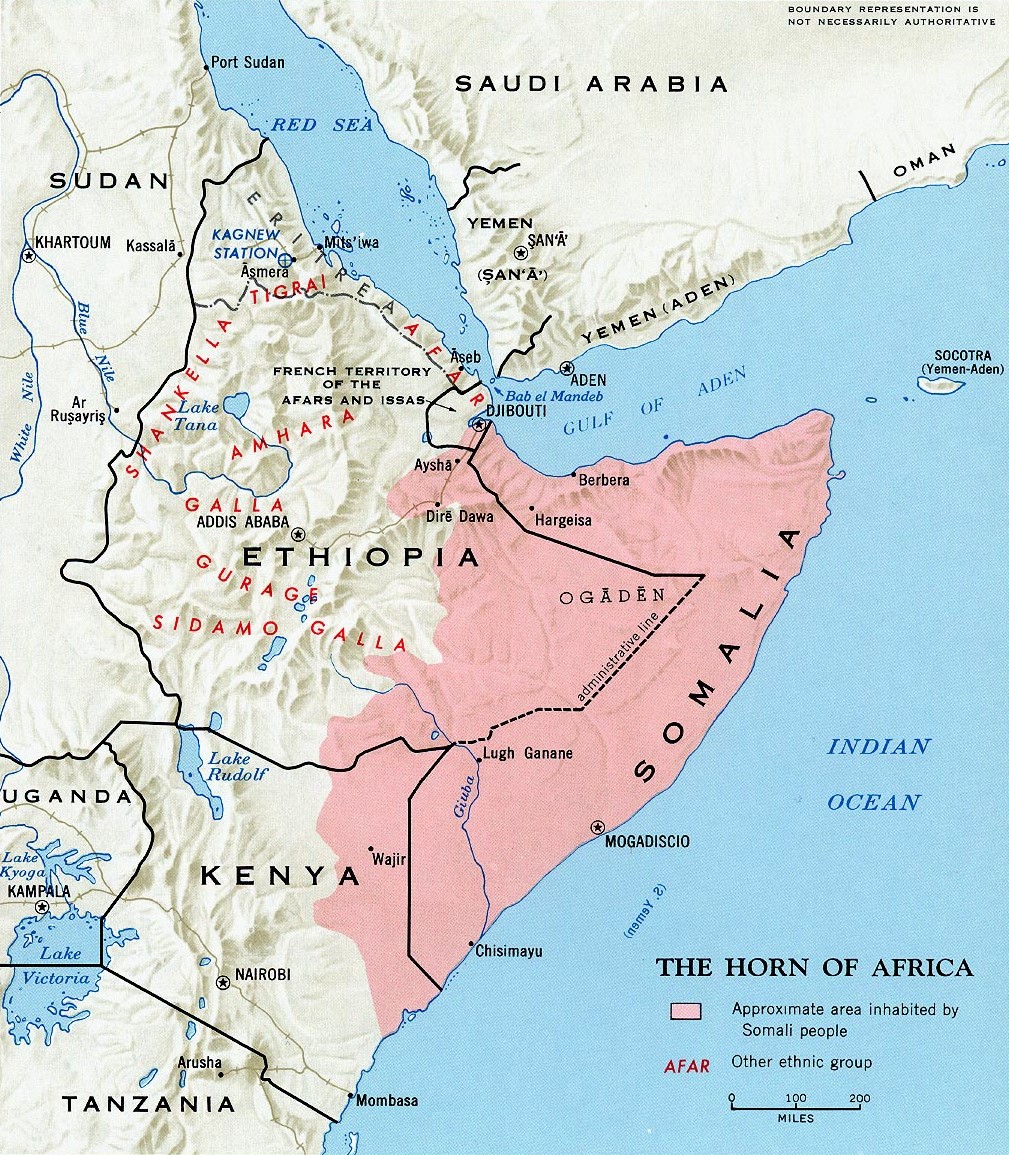

In its efforts to expel an Islamist government and capture a handful of inactive al-Qaeda suspects in Somalia, the United States has risked its political reputation in the region through a series of unpopular measures. These include backing an unsuccessful attempt by warlords to take over the country, several ineffective air raids, and finally, the financing of an unpopular Ethiopian military intervention. As African Union peacekeepers struggle to restore stability in the capital of Mogadishu, China has stepped in to sign the first oil exploration deal negotiated by Somalia’s new government. The agreement is the first of its kind since the overthrow of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 began a long period of political chaos in the strategically important nation.

Chinese Oil Rig in South Sudan (Tong Jiang/Imaginechina)

Chinese Oil Rig in South Sudan (Tong Jiang/Imaginechina)

China’s four major oil corporations have unlimited government support, allowing them to edge out the smaller Western oil companies that traditionally take on high-risk exploration projects like Somalia. Latecomers to the global oil game, the Chinese companies and their exploration offshoots have focused on oil-bearing regions neglected by major Western operators because of political turmoil, insecurity, sanctions or embargoes. China once hoped to supply the bulk of its energy needs from deposits in its western province of Xinjiang, but disappointing reserve estimates and an exploding economy have given urgency to China’s drive to secure its energy future. Twenty-five percent of China’s crude oil imports now come from African sources.

The Somalia deal is part of a decades-long Chinese campaign to engage Africa through investment, development aid, “soft loans,” arms sales and technology transfers. The European Union recently warned China that it would not participate in any debt-relief projects involving China’s generous “soft-loans” in Africa (Reuters, July 30).

Global demand for oil is expected to rise over 50 percent in the next two decades even as prices rise and reserves decline. To meet this demand, China and other Asian countries offer massive infrastructure developments in exchange for oil rights. President Hu Jintao and other Chinese leaders are regular visitors to African capitals and Chinese direct investment in Africa totaled $50 billion last year.

Oil in Somalia?

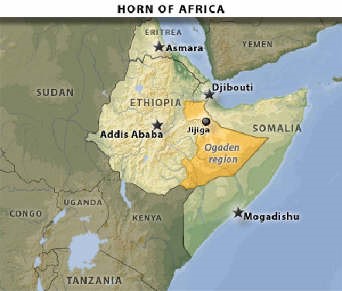

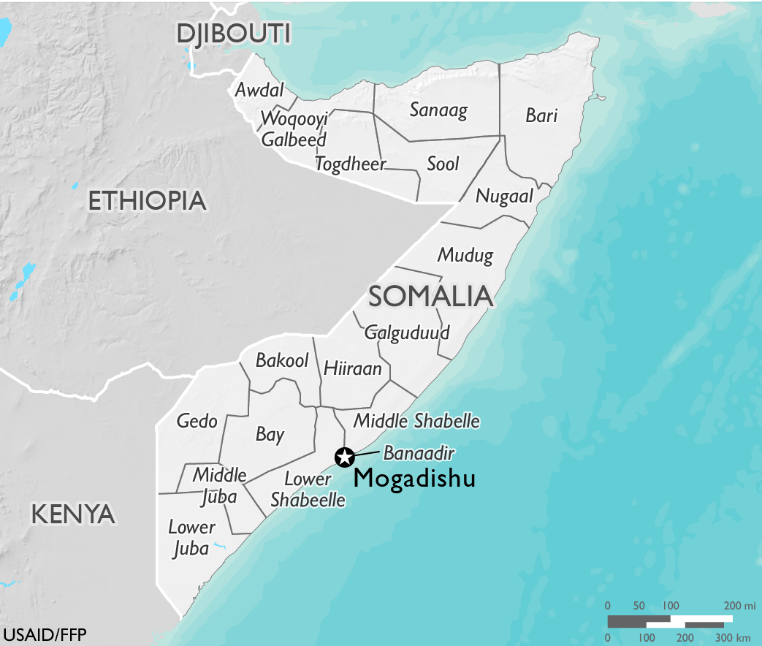

Last month a deal was reached between Somali President Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmad, the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and China International Oil and Gas (CIOG) to begin oil exploration in the Mudug region of the semi-autonomous state of Puntland (northeast Somalia) (Financial Times, July 17). Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government (TFG), which has yet to secure its rule, is to receive 51 percent of the potential revenues under the deal.

Somali President Abdullahi Yusuf (a native of Puntland) appears to have negotiated the deal in concert with Puntland officials but without the knowledge of the Prime Minister, Ali Muhammad Gedi, who is still working on legislation governing the oil industry and production-sharing agreements. Gedi insists that “in order to protect the wealth of the country and the interests of the Somali people, we cannot operate without a regulatory body, without rules and regulations” (Financial Times, July 17). The agreement with China may become an important test of the authority of the transitional government. China has effectively pre-empted the return of Western oil interests to Somalia, though it is unclear how the Chinese project may be affected by the passage of a new national oil bill. Somali negotiators assured the Chinese firms that new legislation would have no impact on exploration work due to begin in September (Shabelle Media Network, July 17).

Though Somalia has no proven reserves of oil, Range Resources, a small Australian oil company already active in Puntland, suggests that the area might yield 5 to 10 billion barrels (Shabelle Media Network, July 14). Somalia is also estimated to have 200 billion cubic feet of untapped natural gas reserves. Western petroleum corporations, however, conducted extensive exploration of potential oil-bearing sites in Somalia in the 1980s and found nothing worth developing.

Public unrest is already on the rise in Puntland as the local government grows increasingly authoritarian and the national treasury has mysteriously dried up. Discontent has accelerated as leaders of the one-party regime continue to sign resource development deals with Western and Arab companies without any form of public consultation. The new deal with China has the potential to ignite political unrest in one of the few areas of Somalia to have avoided the worst of the nation’s brutal political nightmare.

China’s Strategy in Africa

Last November, Beijing hosted an important summit meeting between Chinese leaders and representatives of 48 African countries. The African delegates gave unanimous support to a declaration endorsing a one-China policy and “China’s peaceful reunification” [1]. China in turn announced a $5 billion African development fund (administered by China’s Eximbank), with a promise of $15 billion more in aid and debt forgiveness to come. In exchange for secure energy supplies, China is also offering barrier-free access to Chinese markets, something Africans have been unable to obtain from the United States or the EU.

While China has had success in securing energy supplies in Africa, its oil offensive is by no means flawless. Chinese corporations working abroad provide little employment for local people and are remarkably tolerant of corruption and human rights abuses. Chinese overseas operations are also notorious for their disregard of environmental considerations. The latter is perhaps unsurprising, considering the environmental devastation afflicting China’s own industrial centers. Yet, the combination of all these factors tends to create unrest in nations where Chinese operations are seen as benefiting members of the ruling elite and few others. What is also notable is that of the five African countries where China is involved in major resource operations, only one, Angola, is not dealing with a major insurgency.

While China has had success in securing energy supplies in Africa, its oil offensive is by no means flawless. Chinese corporations working abroad provide little employment for local people and are remarkably tolerant of corruption and human rights abuses. Chinese overseas operations are also notorious for their disregard of environmental considerations. The latter is perhaps unsurprising, considering the environmental devastation afflicting China’s own industrial centers. Yet, the combination of all these factors tends to create unrest in nations where Chinese operations are seen as benefiting members of the ruling elite and few others. What is also notable is that of the five African countries where China is involved in major resource operations, only one, Angola, is not dealing with a major insurgency.

Sudan

China continues to expand its operations in the Sudan, its most successful foreign energy project to date. Oil from southern Sudan currently supplies 10 percent of China’s imported energy needs. Chinese and Malaysian companies operating as a joint venture (with a minority Sudanese share) stepped up to take over the exploitation of Sudan’s vast oil reserves after international pressure forced out the Canadian Talisman Corporation. The China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) recently announced the acquisition of a 40 percent share in a major exploration site off the Sudanese Red Sea coast. A 1997 embargo prevents U.S. companies from operating in the Sudan.

The Sudanese/Swiss ABCO Corporation claims that preliminary drilling in Darfur revealed “abundant” reserves of oil. These reserves have yet to be confirmed, but it appears that the rights may have already passed into Chinese hands (AlertNet, June 15, 2005; Guardian, June 10, 2005).

Ethiopia

China and Malaysia, partners in the Sudan, are trying to replicate their Sudanese success in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia. As a demonstration of goodwill—and to increase the incentives for cooperation—China and Ethiopia signed a debt relief agreement in May worth $18.5 million (Xinhua, May 30). In addition, a new convention center for the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa is being built with substantial Chinese assistance.

Following its usual practice, China imported its own labor to work in the Ogaden projects in preference to hiring local workers. Asian exploration companies tend to arrive in the region with large military escorts after negotiating contracts with the Tigrean-based government in Addis Ababa. The ethnic-Somali inhabitants of the Ogaden region have little input, making the operations a target of the rebel Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF). A commando unit of the ONLF attacked a well-guarded Chinese oil exploration facility in northern Ogaden on April 24, killing 65 Ethiopian troops and nine Chinese workers. A further seven Chinese workers were abducted “for their own safety” and released a week later (ONLF communiqué, April 24)

Niger

In Niger the CNPC (already active in two other concessions) appears to be in the lead for the sole rights to the promising Agadem concession, to be awarded sometime this month. With financial support from the Chinese government, CNPC is offering to build a refinery and a pipeline in exchange for the rights, a commitment even Western oil giants like Exxon have shied away from. A Tuareg-based rebel movement in the resource rich north has declared Chinese oil and uranium operations “unwelcome” while accusing China of supplying the Niger army with weapons to pacify the region. Rebels attacked an armed supply convoy heading to a CNPC exploration camp in July, killing four soldiers (Reuters, July 31).

Nigeria

Last year, the CNOOC moved into territory previously dominated by major Western oil companies in the Niger Delta, paying $2.7 billion for a 45 percent share in an offshore oilfield expected to go into production in 2008 (Reuters, April 26, 2006). China is building $4 billion worth of oil facilities and other infrastructure in return for access to other promising Nigerian oil-fields, including the untapped inland Chad basin (BBC, April 26, 2006).

With a growing insurgency in the oil-rich Niger Delta threatening Nigeria’s oil industry, China has stepped in to supply weapons, patrol boats and other military equipment. Beijing does not share Washington’s reluctance to supply such hardware to a Nigerian military accused of corruption and human rights violations (Financial Times, February 27). The insurgents claim that Chinese, Dutch and U.S. resource companies fail to hire local labor and are devastating the local economy and environment through unchecked pollution. The world’s eighth largest oil exporter, Nigeria is also a major market for Chinese exports.

Angola

Beijing has been wooing oil-rich Angola through promises of aid and development. Its promise of $2 billion in soft loans brought a guarantee of uninterrupted oil supplies to China and offshore exploration rights for CNPC while enabling Angola to avoid Western pressure to restructure a corrupt and inefficient economy.

Competition with the United States

As China intensifies its economic engagement with Africa, the United States has been steadily increasing its military presence in Africa, supplying arms, training troops and opening new bases for U.S. personnel. Efforts such as the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Initiative have brought U.S. forces into many countries for the first time as part of the global effort against al-Qaeda. The creation last February of AFRICOM, a new U.S. regional combatant command for Africa, reflects Washington’s new interest in the area. Despite the anti-terrorism rhetoric, it appears that the main function of AFRICOM will be to secure U.S. energy supplies in a region that is expected to provide a growing share of the United States’ future energy needs.

Ironically, U.S. arms and military training provided under the guise of “counter-terrorism assistance” may ultimately provide Chinese oil interests with the security they need to carry out operations in high-risk areas. An Ethiopian army financed and equipped by the United States for use against “Al-Qaeda terrorists in Somalia” is now being used to protect Chinese oil exploration efforts in the Ogaden region through military operations against ONLF rebels and punitive attacks on ethnic-Somali civilians.

Conclusion

So far, a visible disinterest in tying resource development contracts to social or economic reforms has aided China in securing its energy future in Africa. To be fair, this pattern of tolerance for corruption in regimes with desirable natural resources was set long ago by Western corporations and governments. China still employs the rhetoric of anti-colonialism in its relations with Africa, but many Africans are beginning to see China as an exploitive major power supporting corrupt regimes in the same manner as the former Western imperial powers. While China is taking some small steps to correct this impression, problems will persist unless Africans see immediate benefits from the Chinese presence, particularly in the field of employment. China’s success in presenting itself to the Third World as “the largest developing country” will eventually have limited currency if its business operations become indistinguishable from Western corporations. In the meantime, China’s rivalry with the West for control of Africa’s oil is certain to intensify.

Notes

- See the full text of the Declaration of the Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, available online at: english.focacsummit.org/2006-11/16/content_6586.htm.