Andrew McGregor

June 29, 2012

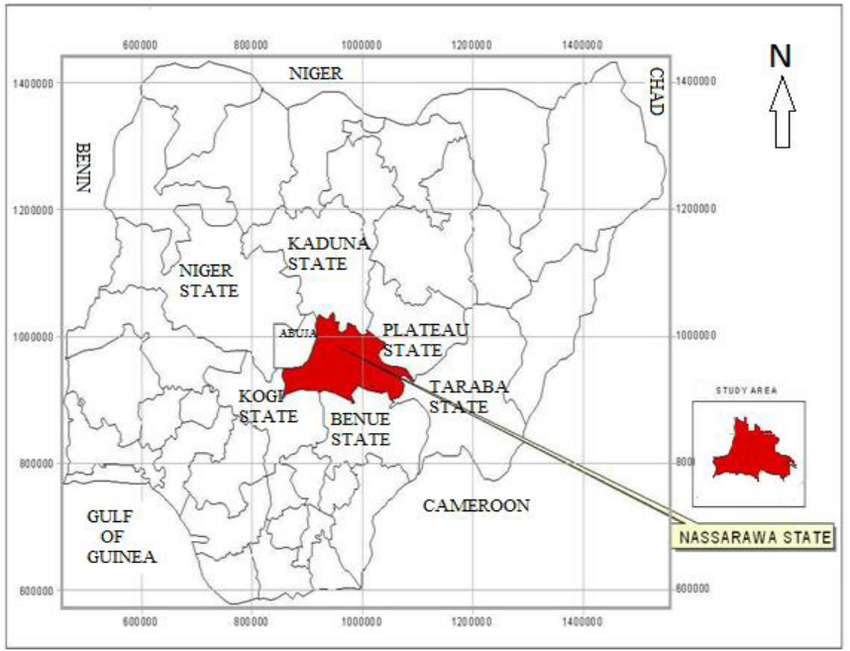

A statement from the Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) issued on June 21 warned that last week’s Boko Haram attacks on Christians in Kaduna and Zaria and the subsequent reprisals against innocent Muslims represented a descent into a complete social breakdown in Nigeria “reminiscent of the horrific inter-ethnic and religious war that marked the violent break-up of the former Yugoslavia” (Nigerian Tribune, June 21). As the crisis mounts in Nigeria, the recent and surprising release from prison of a former leader of sectarian violence in northern Nigeria has almost been overlooked, but in itself threatens a resumption of the murderous outrages of the Maitatsine movement of the early 1980s that claimed nearly 10,000 lives and nearly shattered Nigeria’s social and political order. Though not identical in ideology, the ongoing violence of the Boko Haram movement in many ways takes its inspiration from one of the most dreaded and controversial figures in post-independence Nigeria – the late Mallam Muhammadu Marwa, better known by his Hausa nickname, “Maitatsine,” or “The One Who Damns.” As his successor Makaniki returns to the streets of northern Nigeria, it is worthwhile to re-examine the life of Muhammadu Marwa, a man who sought not merely to reform Islam, but to change it completely, regardless of the cost in blood this would require.

Early Life of Muhammadu Marwa

Though Marwa was born a member of the powerful and widespread Fulani tribe in the town of Marwa in northern Cameroon (close to the Nigerian border), we know little of his early life before he emerged as a young itinerant mallam (Islamic teacher). [1] From the beginning, there were aspects to his teaching that orthodox Muslims found provocative, and it was not long before authorities in British Cameroon quietly pushed him across the border to British-occupied Nigeria in 1945 in the hopes he would become someone else’s problem. [2] Physically, Marwa was described as unimposing; a small, slender man, soft-spoken in his early days, bearded and with two gold incisor teeth. [3]

Central Mosque, Kano

Marwa arrived in the garb of a religious scholar in Kano in the 1950s, where his idiosyncratic interpretation of Islam and claims that Muhammad was not an actual prophet drew his presence to the attention of Ado Bayero, the Emir of Kano, who had the controversial preacher shipped back to Cameroon in 1962. His residency there was short-lived; however, as local Cameroonian authorities facilitated the return of this disturbing individual to Nigeria in 1966, where he established himself as a Quranic teacher to young boys, a situation that permitted him to begin building a loyal following indoctrinated in his particular interpretation of Islam, though not before he served another stretch in prison beginning in 1973 when authorities objected to his methods and teachings. [4] This incarceration appeared to have little effect on Marwa’s progress in Kano, and it was not long before his followers began to comb the city for homeless youth who could be easily enticed by promises of food and shelter. With a development boom infused with petrodollars, Kano went from a city of 400,000 people largely confined within the old city walls in 1970 to a sprawling metropolis of 1.7 million people only ten years later. Wealth remained concentrated in the hands of a privileged few, however, and the streets of Kano were filled with young people seeking any means of survival. [5] In building his following, Marwa made full use of the almajiri system in which boys, usually between ten to 14 years-old, were attached to a religious teacher who provided sufficient instruction in Arabic to permit the reading and memorization of Islamic scriptures.

The students were largely self-supporting through daily begging for alms (a traditional means of support for religious students), a portion of which went directly to Marwa. The movement’s funding was supplemented by Marwa’s growing reputation as a composer of allegedly powerful amulets and charms, an activity shunned by better-educated religious scholars, but one that appealed to a wide spectrum of Muslims still influenced by traditional interpretations of Islam that incorporated pre-Islamic belief systems. Marwa’s efforts in this area hearkened back to the 1906 Mahdist Satiru Rebellion in northern Nigeria, in which a briefly successful uprising eventually came to grief when insurgents eschewed the use of fire-arms in favor of traditional weapons and charms produced by a holy man named Dan Makafo that promised to turn bullets into water. [6]

Building a Base for Islamic Renewal in Kano

During the 1970s, Marwa began to take on the established Sunni scholars, condemning anyone who used any other scriptural source than the Quran, including the Sunna and the Hadiths. [7] More broadly, he damned those who read any book other than the Quran or used watches cars, bicycles, televisions, cigarettes and many other products that reflected Western life, earning himself the nickname “Maitatsine,” or “The One Who Damns.” By the late 1970’s, Marwa had become a well-known public figure by challenging all manner of authority. Such activities earned him a year in prison at hard labor in 1978, but this did little to deter him. Indeed, Marwa grew more powerful from this point as his followers began appropriating properties beside his Quaranic school, eventually developing a self-ruling enclave of several thousand men to which opponents and alleged “traitors” to the movement were brought and summarily executed after a brief and predictable appearance before the movement’s own “court.” [8]

The 1979 Iranian Revolution encouraged the growing millenarian trend in the Muslim community and Marwa’s own followers became increasingly violent in their rejection of state authority, partly by exploiting the greater degree of political and individual freedom promulgated by Nigeria’s 1979 constitution. The growing tensions in northern Nigeria’s Islamic community led to dozens of clashes between authorities and various Islamic groups in the lead-up to the Kano insurrection of 1980. Marwa began work on a new center for his followers, located in the unfinished ‘Yan Awaki district of Kano. The fortified compound was based on high ground and partly protected by a stream that wound round part of the property. A separate one-storey building at the rear of the compound was known as “the slaughter-house,” where numerous victims of the sect were murdered and their bodies dumped through a trap-door into the stream. Efforts to rein in Marwa through legislation against unorthodox preaching failed through fears it could be applied against the more mainstream ulema (religious scholars and clergy) and the Maitatsine enclave and its surroundings became a “no-go” area for local police. Even undercover work was abandoned, leaving security forces with little intelligence regarding the movement’s intentions. In the absence of any opposition by authorities, Marwa continued to illegally expropriate neighboring properties and encouraged his supporters to settle on any unoccupied real estate, asserting that all land belonged to Allah and his people. By 1980, Marwa had roughly 10,000 followers (mostly in Kano but with smaller groups in Bauchi, Gombe, Maiduguri and Yola) and confrontations with police and the ulema became common, often degenerating into pitched street-battles with multiple fatalities.

Marwa was accompanied by bodyguards everywhere and his followers began to appear armed at public events, having received training under the supervision of the movement’s military commander Saidu Rabiu from former soldiers and policemen who had joined the movement. It was common for sect members to carry concealed weapons in the streets while confident of the protection against firearms and other weapons bestowed by the charms and amulets produced by Marwa. [9] In this atmosphere it became clear that matters would soon come to a head, especially when rumors began to circulate that Marwa intended to take over Kano’s market and main mosques. [10] Nonetheless, authorities in Lagos denied repeated requests from Kano for police reinforcements to deal with Marwa and his followers, who by this time vastly outnumbered the available police in Kano.

Beyond Orthodoxy

Marwa’s message appealed to the largely unemployed or underemployed masses that the rapid expansion of Kano attracted from the Nigerian countryside and even from across regional borders, many of whom could not afford the consumer goods denounced by the increasingly bellicose religious leader. Marwa’s prohibition against carrying only small amounts of cash on the grounds that carrying more displayed a lack of faith in Allah did not require much adaptation by the migrants, working poor and impoverished students who flocked to his leadership, who were often inspired as much by resentment against the flourishing corruption and mismanagement that concentrated money in the hands of a few as by religious concerns. The anti-materialist theme in Marwa’s teachings gave focus to the lives of the impoverished, replacing envy with righteousness. Though Marwa sought to reform Islam through a highly individual interpretation of what constituted orthodoxy, he did not hesitate to employ older, pre-Islamic spiritual beliefs regarding the concentration of magical powers in certain individuals, traditions that were familiar to his largely rural-origin following. Marwa also changed the wording and the ritual involved in daily prayer, a shocking display of arrogance to most Muslims. Most controversial, however, was Marwa’s 1979 claim to be a nabi, or prophet, at times equating himself with the Prophet Muhammad, and at other times declaring his superiority to this “mere Arab.” [11] For orthodox Muslims, who believe Muhammad is the last Prophet, Marwa had now gone beyond all reasonable interpretations of Islam and placed himself at odds with the larger Muslim community in northern Nigeria.

An Inevitable Confrontation

In response to public complaints, Kano State governor Muhammad Rimi (who was alleged to have previously had ties to the cult) sent Marwa a message on November 24, 1980 demanding that he and his followers vacate their illegally expropriated holdings or face government action. Marwa, in turn, began summoning his followers to his defense.

When police attempted to prevent a public demonstration by arresting some leaders of the ‘Yan Tatsine (as Marwa’s followers were known) at Kano’s Shahuci Playing Grounds on December 18, 1980, they were attacked by ‘Yan Tatsine wielding machetes, knives, spears, axes and bows and arrows. Police arms quickly fell into the eager hands of the ‘Yan Tatsine and it did not take long for the security forces to lose control of the situation entirely. Kano was turned over to mobs of ‘Yan Tatsine who murdered, raped and pillaged in the city for days, often while singing movement favorites like Yau Zamu Sha Jini (“Today We Will Suck Blood”). [12] At times the marauders were opposed by vigilante groups (the ‘Yan Tauri), but these were generally ineffective as supporters of Marwa continued to pour into the city. [13] By December 22, with many of the outnumbered and demoralized police no longer showing up for duty, it was felt necessary to deploy the Nigerian military to retake Kano, which they began by “softening up” the militants (and their unfortunate neighbors) with a ten-hour mortar barrage by the 146th Infantry Battalion, together with aerial support. Militants and innocents alike perished in the bombardment, which was followed by military forces mopping up the remaining resistance with rockets and machine guns in bitter street fighting. Battalion Major Haliru Akilu noted later that the militants showed little fear of the Army’s superior weapons: “They were ready to kill first, or be killed, but never to run” (The Age [Lagos], February 21, 1981).

A contributing factor to the ferocity of the onslaught of the ‘Yan Tatsine on the ordinary citizens of Kano appears to have been the death shortly before the clashes of Marwa’s eldest son Tijani (a.k.a. Kana’ana). Though Tijani appears to have opted for association with members of Kano’s criminal underworld rather than the pursuit of religion, Marwa blamed Tijani’s death at the hands of his criminal associates on the people of Kano as a whole and vowed to make every father “taste the bitterness of losing a child” (Sunday Trust [Abuja], December 26, 2010).

Separated by only a decade from a bitter civil war, Nigeria’s largely northern ruling class was in no mood to tolerate such challenges to its authority or national unity. Official figures claimed over 4,000 dead, though other sources suggest the figure was far larger. At least 100,000 people were displaced by the fighting. [14] Hundreds of children abducted by the sect for indoctrination were also freed when soldiers entered the Maitatsine compound.

Rumors that the insurgents had been aided by Libyan troops or provided with Libyan arms soon proved false (Libyan troops were fighting across the border in Chad at the time). Other claims that “Zionist forces” or various Western intelligence agencies were behind the rebellion were raised at the subsequent Aniagolu Commission of Inquiry but remained unsubstantiated. [15] The Zionist allegation appears to have had its origin in the sect’s practice of praying while facing Jerusalem rather than Mecca. [16]

The Legacy of Maitatsine

Once the Army had retaken control of Kano, Marwa’s body was exhumed from a shallow grave on the outskirts of the city (News Agency of Nigeria, December 31, 1980). The would-be prophet was variously reported to have died from smoke inhalation or wounds to his leg during the attack on his compound (The Age, February 21, 1981). [17] On the orders of Justice Aniagolu the remains were cremated and remain today in an officially sealed jar on the shelf of the police laboratory in Kano (Sunday Trust [Abuja], December 26, 2010). The area where Marwa built his enclave is now home to a police barracks, all traces of the former complex having been destroyed in the fighting or demolished soon afterwards.

In the commission of inquiry that followed the devastation of Kano, there was inevitable criticism of police efforts. Most of the police rank-and-file came from the same culture as the members of the ‘Yan Tatsine, and were just as prone to believing in the efficacy of the charms and amulets worn by Marwa’s followers. Their leaders also came under criticism, with the commission declaring the acting commissioner of police at the time “had totally succumbed to the permanent existence of the threat, which like the state governor and other government functionaries, was believed to be beyond suppression. It was a case of total surrender to an overwhelming situation” (Sunday Trust [Abuja], December 26, 2010).

Attempts by some Nigerian authorities to create an “Outsider Narrative” to explain the events in Kano were not supported by evidence. Police records confirm that Nigeriens, Chadians and Cameroonians were among Marwa’s followers arrested after the 1980 uprising, but their numbers were relatively small and did not justify government attempts to characterize the ‘Yan Tatsine as a “foreign” movement that had infiltrated Nigeria.

Marwa’s rise took place at a time and in a region where Islam was perhaps more of a divisive than a unifying force. There was intense competition between the major Sufi orders (the Qadiriya and the Tijaniya), Saudi-inspired Salafists, anti-Sufists of the Saudi-supported ‘Yan Izala movement and politically conscious Muslims inspired by the 1979 Iranian revolution. Wrapped in a resolutely anti-authoritarian, anti-state and anti-materialist garb, Marwa was able to present himself as the final prophet of Islam based on the millenarian fervor existing in the Islamic year AH 1400 (1979-1980). In doing so, Marwa exploited strong currents of Mahdism in the region, which was in expectation of a mujaddid, or “Renewer,” an individual believed to appear at the end of every century (on the Islamic calendar) to restore Islam to its original purity. The strength of these beliefs not only gave Marwa a certain degree of immunity in the Muslim community, but also allowed for the close connections he was alleged to have with certain politicians and prominent businessmen in the area.

Despite the deaths in Kano and the arrest of several thousand of Marwa’s supporters, the ‘Yan Tatsine continued to exist, though much of the movement relocated to the city of Maiduguri in Borno State. Drawing strength from the belief that Marwa was not actually dead, the movement was soon operating in defiance of the state once more.

- · October, 1982 – A ‘Yan Tatsine clash with police at Bulunkutu, outside Maiduguri, left over 450 dead before the fighting spread to Kaduna State, where scores more were killed.

- · February, 1984 – More than 1,000 people were killed during rampages in Jimeta (Gongola State) that followed the mass escape of ‘Yan Tatsine from a local jail.

- · April, 1985 – Efforts to arrest Marwa’s successor al-Makaniki (“the Mechanic,” a.k.a. Yusufu Amadu) in Gombe (Bauchi State) left at least another 150 dead after the ‘Yan Tatsine engaged in a gunfight with security forces. Makaniki fled to Cameroon, where he remained until 2004, when he returned to Nigeria and was arrested. In a surprise development, Makaniki was acquitted and discharged as a free man in early May, 2012 (Daily Trust [Abuja], May 9).

In 2006, one of Maitatsine’s wives, Zainab, told a reporter that Marwa had nothing to do with the Kano violence in 1980 and that her late husband was “an embodiment of scholarship, a father and a religious reformer that was misunderstood. He preached tolerance, peace, harmony and religious revival… To the best of our understanding of him, he was a man of humility and we are sure he was framed, misunderstood and castigated for preaching” (Sunday Trust [Abuja], December 26, 2010). While most Nigerians reject such an interpretation of the Maitatsine legacy, the calculated viciousness of contemporary attacks by Boko Haram extremists against Muslims and Christians alike suggest that religious extremism, police corruption, lack of opportunity, inept intelligence work, economic inequity and uninhibited urban growth continue to provide fertile ground for periodic and uncontrollable explosions of religiously-inspired violence in northern Nigeria.

Notes

1. For contemporary Fulani militancy in Africa, see Andrew McGregor, “Central Africa’s Tribal Marauder: A Profile of Fulani Insurgent Leader General Abdel Kader Baba Laddé,” Militant Leadership Monitor 3(4), April 30, 2012.

2. Francis Ohanyido, “Poverty and Politics at The Bottom of Terror (Part 1 – The Maitatsine Phenomenon),” Ayaka 3(2), June 2012, http://www.ayakaonline.com/politics/poverty-and-politics-at-the-bottom-of-terror-part-1-%E2%80%93-the-maitatsine-phenomenon/

3. Toyin Falola, Violence in Nigeria: The Crisis of Religious Politics and Secular Ideologies, Rochester, 1998, p.141.

4. The dates of Marwa’s various convictions and the duration of his sentences are a matter of some dispute in the literature concerning him and is likely due to inconsistent record-keeping.

5. Michael Watts, “Black Gold, White Heat: State violence, local resistance and the national question in Nigeria,” in: Michael Keith and Steven Pile (eds.), Geographies of Resistance, London, 1997, p.47.

6. J.S. Hogendorn and Paul E. Lovejoy, “Revolutionary Mahdism and Resistance to Early Colonial Rule in Northern Nigeria and Niger,” African Studies Seminar Paper, African Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand, May 1979, pp.26-27.

7. Niels Kastfelt, “Rumours of Maitatsine: A Note on Political Culture in Northern Nigeria,” African Affairs 83(350), 1989, p. 83.

8. Paul Collier and Nicholas Sambanis, Understanding Civil War: Africa: Evidence and Analysis, World Bank Publications, 2005, p.103.

9. Falola, op cit, p.146.

10. Rosalind I.J. Hackett, “Exploring Theories of Religious Violence: Nigeria’s ‘Maitatsine’ Phenomenon,” in: Timothy Light and Brian C. Wilson (eds.), Religion as a Human Capacity: A Festschrift in Honor of E. Thomas Lawson, Leiden, 2004, p.197.

11. Falola, op cit, p.143.

12. Ibid, p.154.

13. Allan Pred and Michael John Watts, Reworking Modernity: Capitalisms and Symbolic Discontent, Rutgers, 1992, p.24.

14. Watts, op cit, p.55.

15. Elizabeth Isichei,“The Maitatsine Risings in Nigeria 1980-85: A Revolt of the Disinherited,” Journal of Religion in Africa 17(3), October 1987, pp.76-78.

16. Hackett, op cit, pp.199-200.

17. Abdur Rahman I. Doi, Islam in Nigeria, Zaria, 1984, p.299.

This article was first published in the June 29, 2012 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Militant Leadership Monitor