Eurasia Daily Monitor 14(158)

December 6, 2017

Though Sudan’s national economy is near collapse, the November 23 visit of Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir to Russia’s top leadership in Sochi was dominated by expensive arms purchases and Sudan’s appeal to Russia for “protection from aggressive actions by the United States” (TASS, November 23; see EDM, November 29). A suggestion that Khartoum was ready to host Russian military bases took most Sudanese by surprise, given that Washington lifted 20-year-old economic sanctions against Sudan in October and relations with the US finally seemed to be improving.

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir (AFP/Ashraf Shazly)

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir (AFP/Ashraf Shazly)

Al-Bashir expressed Sudan’s interest in purchasing the highly maneuverable Russian-made Sukhoi Su-30 and Su-35 fighter jets during the Sochi visit. And in fact, an unknown number of Su-35s were reportedly delivered days ahead of al-Bashir’s visit, making Sudan the first Arab country to have the aircraft (RIA Novosti, November 25; al-Arabiya, November 20).

Khartoum announced its intention to replace its Chinese and Soviet-era aircraft in March, when Air Force chief Salahuddin Abd al-Khaliq Said declared Sudan would henceforth be “fully dependent on Russia for its air armament” (Defenceweb, November 29).

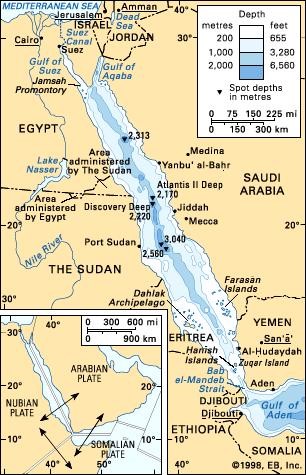

The Su-35, deployed in Syria by the Russian Air Force, is one of the best non-stealth fighters and missile-delivery platforms available, but at an export price of as much as $80 million each, cash-strapped Khartoum may have to provide other forms of compensation. It may have been no surprise then that Sudan’s delegation in Sochi expressed willingness to host Russian naval bases along its 420-mile Red Sea coastline (Sputnik News, November 28). However, there are few suitable places for such bases on the coast, where transportation infrastructure is poor.

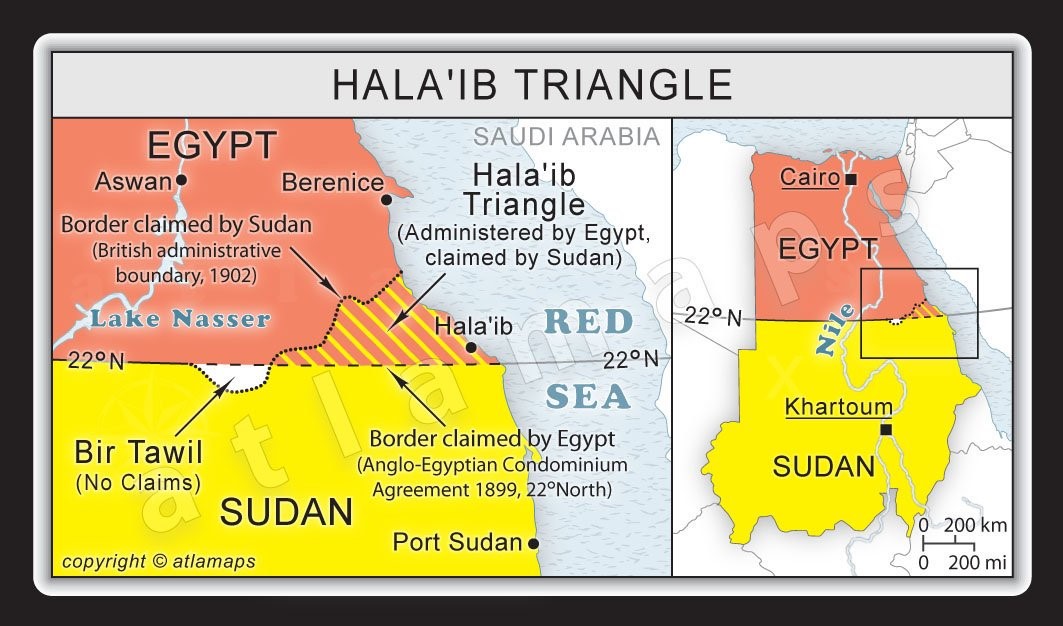

Suakin, the coast’s historic port, was replaced in 1909 by the newly built Port Sudan, able to accommodate the large steamers Suakin could not. Otherwise the coastline has only a handful of small harbors (sharm-s) suitable only for dhows and fishing boats. Sailors must cope with coral reefs, shoals and numerous islets. Gaps in the large reef that runs parallel to the coast determined the location of both Suakin and Port Sudan. The entire coast is notoriously short of fresh water, a problem that must be accounted for before the construction of any large facilities. Though Egypt’s own military ties with Russia are growing, Cairo is unlikely to welcome a Russian naval base on the Red Sea coast, where Egypt currently contests possession of the Hala’ib Triangle with Sudan. [1]

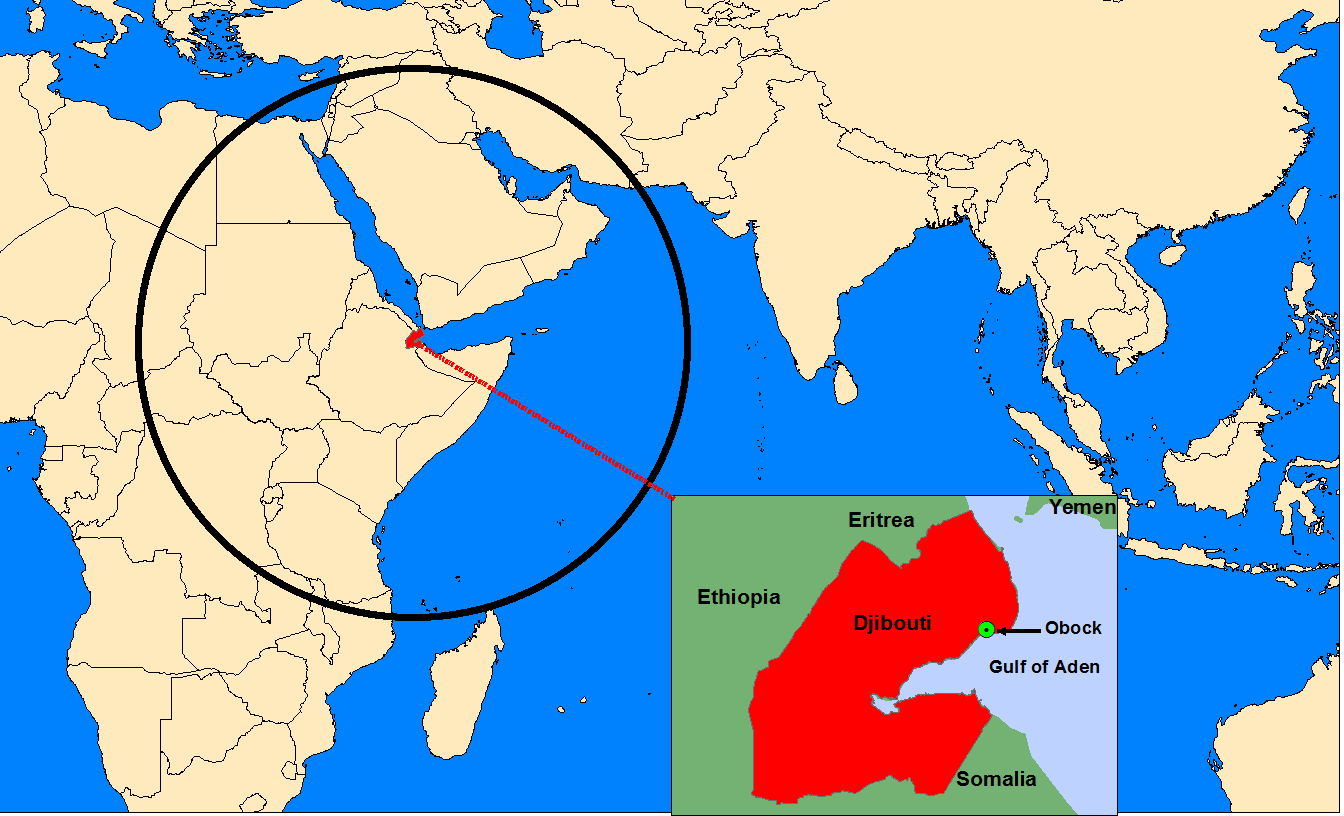

Djibouti, with its vast harbor and strategic location on the Bab al-Mandab strait would make a far better base for Russian naval operations in the Red Sea. Russian Cossacks first tried to seize the region in 1889, but now existing US, French and Chinese military bases there (along with an incoming Saudi base) make such a proposition unlikely. Russian naval ships on anti-piracy operations in the Red Sea have used Djibouti for resupply and maintenance.

Djibouti, with its vast harbor and strategic location on the Bab al-Mandab strait would make a far better base for Russian naval operations in the Red Sea. Russian Cossacks first tried to seize the region in 1889, but now existing US, French and Chinese military bases there (along with an incoming Saudi base) make such a proposition unlikely. Russian naval ships on anti-piracy operations in the Red Sea have used Djibouti for resupply and maintenance.

Moscow is also providing Khartoum with 170 T-72 main battle tanks under a 2016 deal; and the latter has expressed interest in buying the Russian S-300 air-defense system as well as minesweepers and missile boats (Xinhua, November 25). Though Sudan still uses a great deal of military equipment of Chinese and Iranian origin, al-Bashir opened the possibility of hosting Russian military personnel when he claimed, “All of our equipment is Russian, so we need advisors in this area” (RIA Novosti, November 25). The BBC’s Russian service has reported unconfirmed rumors of Russian mercenaries operating in Sudan or South Sudan (BBC News—Russian service, December 4).

Two other factors weigh in on Khartoum’s improving relations with Russia:

Gold: President Putin was reported to have confirmed Russia’s continuing support in preventing US- and British-backed United Nations Security Council sanctions on exports of Sudanese gold due to irregularities in Sudan’s mostly artisanal gold industry in Darfur (SUNA, November 23). Since Sudan’s loss of oil revenues with the 2011 separation of South Sudan, gold has become Sudan’s largest source of hard currency, but Khartoum’s inability to control extraction has led to huge losses in tax revenues and has helped fund regime opponents in Darfur (Aberfoylesecurity.com, October 15). Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour explained that it was in this context that al-Bashir’s remarks regarding “Russian protection” were made (Sudan Tribune, November 25).

War Crimes: Al-Bashir recently learned that Washington does not want to see him seek another term as president in the 2020 elections (Sudan Tribune, November 27). The 73-year-old has ruled Sudan since 1989, but retirement seems elusive—al-Bashir’s best defense against being tried by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged war crimes in Darfur is to remain president. Russia withdrew from the ICC in November 2016, calling it “one-sided and inefficient” (BBC News, November 16, 2016).

Khartoum’s request for Russian “protection” was best explained by Sudanese Deputy Prime Minister Mubarak Fadl al-Mahdi, who said the outreach to Moscow was intended to create a new balance: “We can at least limit American pressure, which cannot be confronted without international support… But with Russia’s support at international forums and the Security Council, American demands will be reasonable and help in accelerating normalization of ties” (Asharq al-Awsat, December 3).

However, the Sudanese regime’s nervousness over how this abrupt turn in foreign policy will be received at home was reflected in a wave of confiscations by the security services of Sudanese newspapers that had covered al-Bashir’s discussions in Sochi (Radio Dabanga, November 30).

Jibril Ibrahim, the leader of Darfur’s rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), insisted that al-Bashir’s request for Russian protection and willingness to accommodate Russian military bases had destroyed attempts to normalize relations with the US and was an opening to bring down the Khartoum regime (Sudan Tribune, November 27).

Is Sudan playing a double game here? Foreign Minister Ghandour claims “there is nothing to prevent Sudan from cooperating with the United States while at the same time pursuing strategic relations with China and Russia” (Sudan Tribune, November 25). Nonetheless, al-Bashir has so far avoided becoming anyone’s client and is likely aware that pursuing this new relationship with Russia to the point of welcoming Russian military bases could be his undoing as he seeks to reaffirm his rule over a restless nation in 2020. For this reason, Russian military bases on the barren and furnace-like Sudanese Red Sea coast seem unlikely for now.

Note

- For a detailed map of Sudan’s Red Sea coast, see: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/map_2990.pdf