Andrew McGregor

June 14, 2013

There are signs that the scattered remnants of the Islamist coalition that occupied northern Mali for nine months are beginning to use their financial resources and pre-planned alternative bases to regroup in the Sahel/Sahara region in order to carry out new operations against their targets – the “apostate” governments of the region, local security infrastructure and the considerable French economic interests and personnel found in the region. Though the Islamist took heavy losses in the French-led intervention that drove them from northern Mali, the extremist groups were not trapped and destroyed in the hastily conceived operation. Rather, they have been relieved of a strategic disadvantage, the fixed occupation of certain territories, and regained their number one tactical asset – mobility.

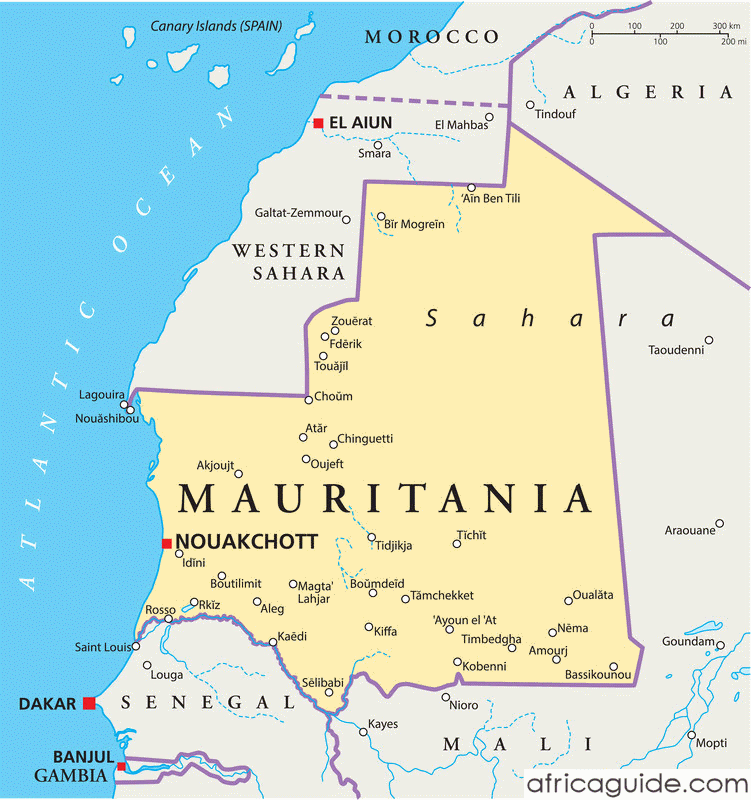

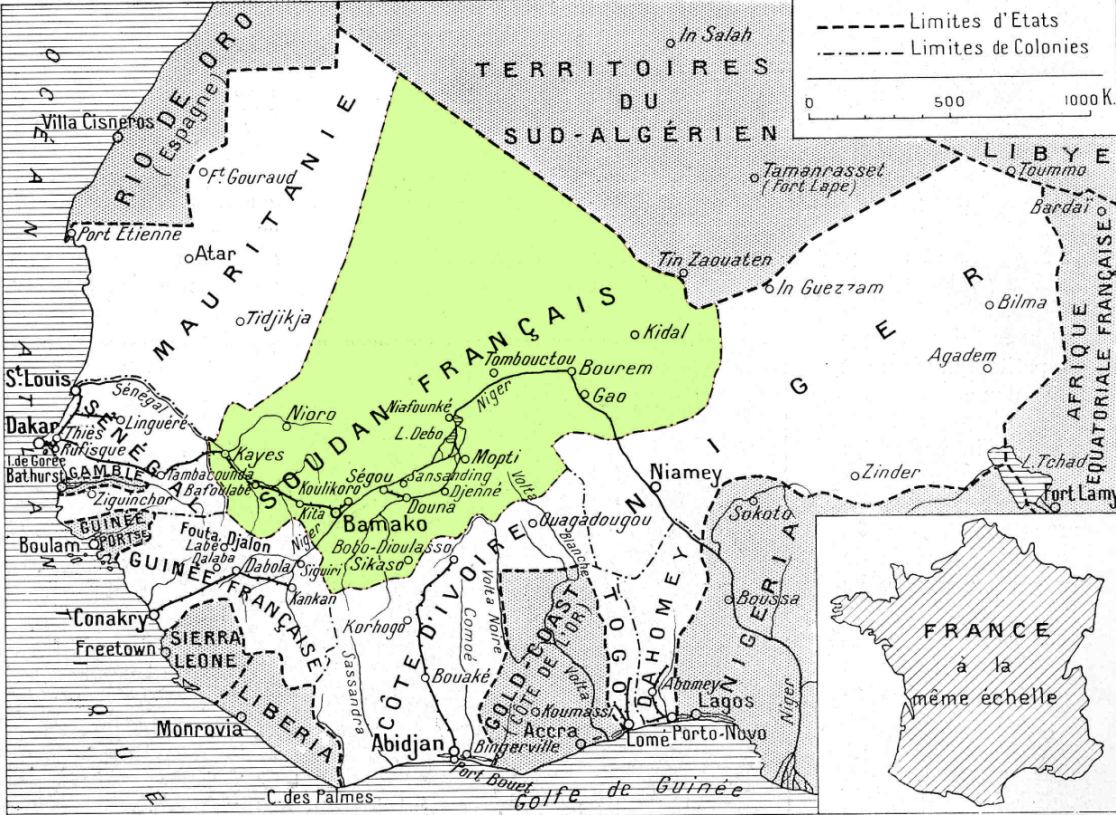

The Sahel

The Sahel

An examination of the regional and international aspects of the ongoing struggle in the Sahel/Sahara helps shed some light on the direction the battle between the Islamists and African states is taking at the half-way point of 2013.

Southern Libya: A Hub for Terrorism?

Southern Libya remains in turmoil, with frequent clashes between African Tubu nomads and Arab tribes preventing effective security measures from being implemented. According to Jouma Koussiya, a Tubu activist, one of the main problems is the government’s reliance on northern militias and northern commanders to provide security in the region, a policy that is actually weakening government control in southern Libya: “They know nothing about the region and they ultimately fail. Now tribes are working together to form a unified military council in order to secure the region, instead of the government” (AP, June 3).

There are also unforeseen dangers to be encountered; on Libya’s southern border with Chad, five members of the Martyr Sulayman Bu-Matara Battalion doing border patrols were recently abducted during a prolonged firefight by gunmen believed to be from Chad (al-Hurra [Benghazi], June 2; al-Tadamus [Benghazi], June 1; May 30). One of the main problems in securing the south remains the unwillingness of northern troops and militia members to serve in the harsh and unfamiliar conditions prevailing in the Libyan Desert. To remedy this, Prime Minister Ali Zeidan has announced that bonuses of $1200 will be paid out to soldiers and militia members willing to work in the region. The announcement is part of a new government strategy to secure the towns and cities of the region first before beginning a second phase of operations to secure and monitor the vast border regions of the south (AFP, June 2).

Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan insists claims that the attackers who struck a military barracks in the Nigérien city of Agadez and a French uranium facility near the Nigérien town of Arlit on May 23 came from southern Libya are “without basis,” saying that the export of terrorism was a practice of the Qaddafi regime but would not be tolerated in “the new Libya” (AFP, May 28). Defense Minister Muhammad al-Barghathi also denies that there is any security crisis in Libya, suggesting the situation is “stable,” asserting that the militias are doing important work under the control of the Defense Ministry and refuting reports that French security services are tracking al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) elements in southern Libya by claiming that “the al-Qaeda organization does not exist in Libya” (al-Jadidah [Tripoli], May 28; June 2).

Prime Minister Zeidan’s “no problems here” approach to the security crisis in southern Libya has been strongly criticized by some observers within Libya who maintain terrorists have created bases in southern Libya (al-Watan [Tripoli], May 28). Usama al-Juili, the defense minister in the Libyan Transitional National Council that preceded the current General National Congress (GNC) government, has expressed a different view of the security situation in the Libyan south:

The terrorists who had been moving from Libya toward Mali are currently reversing course. Which is to say that they are now heading from Mali toward Libya. So I am not astonished that southern Libya has been turned into a new sanctuary for the terrorists fleeing north Mali. Algeria was right when the country spoke out against the war in Mali. It knew the consequences of it. Algeria, though, has the resources to cope with a new geographic reconfiguration of terrorism after the military offensive in north Mali. As for Libya, it does not have these resources… Closing borders is something useless (Le Temps d’Algerie, June 13).

The disarray in the Libyan security structure prevents effective measures from being taken to secure the south, with the anomalous inclusion of largely independent militias within the security structure creating confusion and insecurity throughout Libya.

Libyan army chief-of-staff General Yusuf al-Mangush, generally viewed as a supporter of the militias, resigned under popular, military and governmental pressure following the June 8 massacre of protesters calling for the disarmament of the Libyan Shield militia that left 31 killed (including four members of the army’s Thunderbolt Special Forces unit who arrived to quell the violence) and 60 wounded. The new acting chief-of-staff, General Salim al-Qnaidy, has warned that “patience is running out with the militias” as he attempts to implement a GNC decision to “end the presence of all brigades and illegal armed formations in Libya even if the use of military force is required” (Quryna al-Jadidah [Benghazi], June 12; Libya News Network, June 9). The Libyan Shield-1 headquarters in Benghazi has since been occupied by government troops belonging to the al-Sa’iqah Special Forces and their heavy weapons seized (al-Watan [Tripoli], June 9). The Libyan Shield-1 commander, Wissam bin Hamid, has taken to the airwaves to denounce the protesters as Qaddafi loyalists and traitors to Libya even as other Libyan Shield bases are scheduled to be occupied by units of the national army (al-Tadamun [Benghazi], June 9; al-Watan [Tripoli], June 9).

The approach of the Libyan political leadership reflects the difficulty of the new Libyan government in asserting its writ in that nation – acknowledging that the government is incapable of controlling its own security situation is to admit the government does not have sovereignty over Libya and is in need of foreign intervention.

A French Role in Libya?

French foreign minister Laurent Fabius indicated two weeks ago that France must “make a special effort on southern Libya,” presumably in excess of the modest Libyan requests for advice and training and equipment for border guards (Libya Herald, June 2). Despite Libyan signals that it intends to grapple with its deteriorating security situation by itself, French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian appeared to hold out the possibility that French forces could be available for a mission in southern Libya if Tripoli desired it: “Libya is a sovereign country that is responsible for its own borders. It has to decide whether it wants extended support from the French or any other European country to secure its borders” (AFP, June 2). Rumors in Libya of an imminent French military intervention in the south prompted a denial from French President FrançoisHollande, who cited the absence of a UN mandate or a request from Libyan authorities for military assistance (AFP, May 31).

President Hollande, who is struggling to gain control of a French African foreign policy that has traditionally been in the hands of a select group of military and business interests, has described a new three-track policy in Africa that will include military training and support, environmental preservation and an emphasis on development that could involve opening European markets to African exporters (Fraternite Matin [Abidjan], June 6). Hollande has also signaled French willingness to provide military assistance at the request of regional governments.

However, a growing military commitment in Africa does not necessarily fit with new cuts to the French military budget that will see a reduction in the number of troops, reduced helicopter capability and a cut in the number of armored vehicles amongst other measures. General Jean-Philippe Margueron, the army second-in-command, has warned that a planned reduction in training raises the possibility of mission failure and the production of “cannon fodder” rather than combat-capable troops (Le Monde [Paris], June 11).

France is now looking to purchase 12 MQ-9 Reaper drones from the United States, with two of these to be permanently deployed in Africa to replace the aging Harfang drone systems currently based alongside U.S. drones in Niamey (AFP, June 11). While the Reapers are the choice of the French Air Force, the defense ministry has said Israel will be looked at as an alternative provider if a deal cannot be made with the United States. France is certain to seek weaponized versions of the Reapers, though Washington has so far been reluctant to provide armed drones to any purchasers, including its NATO allies (Defense Industry Daily, May 31).

Niger – The Latest Target

According to Nigérien President Mahamadou Issoufou, there is little doubt that the suicide bombers that struck a military base in Agadez and a French uranium plant in Arlit on May 23came from southern Libya: “For Niger in particular, the main threat has moved from the Malian border to the Libyan border. I confirm in effect that the enemy who attacked us… comes from the (Libyan) south, where another attack is being prepared against Chad” (AFP, May 28; RFI, May 27). [1] The Libyan Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded to Issoufou’s statement by saying it “did not serve the interests of the two countries” and there was “no evidence of the participation of Libyan elements” (al-Manara, May 27).

Malian security officers say the attacks may actually have been planned by radical Islamists in Tarkint, a town in the remote Tilemsi Valley, which has served as a stronghold for the extremists (RFI, May 31). However, there are also reports from sources in Niger that the May 23 attacks were planned in Derna, a Cyrenaïcan Islamist stronghold on the Mediterranean coast (Jeune Afrique, June 9). The Nigérien intelligence service claims that the jihadists who escaped from Mali are now concentrated in the Ubari and Sabha Oases region of southwest Libya (Jeune Afrique, June 9).

Rhissa ag Boula, formerly a leading Tuareg rebel in northern Niger and now a special adviser to the Nigerien president, says that: “The south of Libya, where anarchy reigns, has become a safe haven for the terrorists hunted in Mali” (AFP, June 1). Another veteran Tuareg rebel leader and current MNLA spokesman Hama ag Sid’Ahmad confirmed the Malian and Libyan origin of the attackers, who belonged to the AQIM-related Movement for Unity and Justice in West Africa (MUJWA) and operated under the coordination of Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s al-Mua’qi’un Biddam Brigade (“Those Who Sign in Blood”):

The terrorist groups got to that region through the Malian and Libyan borders. It’s not complicated; the borders are real sieves. Since [Mokhtar] Belmokhtar is the main organizer, without his presence and that of certain drug barons, MUJWA would not exist… Even if the terrorist leaders no longer have major military resources and they are having mobility difficulties, they have money. They are quietly trying to reorganize, forget the leaders’ quarrels, and unite in order to fight together. It’s the presence of the French Special Forces that is preventing them from reorganizing quickly… (Le Temps.d’Algerie, May 27).

So long as Niger refuses to meet Libyan demands for the extradition of Mu’ammar Qaddafi’s son Sa’adi (who lives under house arrest in Niamey) and several other ex-members of the Qaddafi regime, little can be expected in the way of security cooperation between the two nations. Tripoli has indicated its unhappiness with the Nigerien approach by repatriating thousands of Nigeriens working in Libya whose remittances helped support many citizens of this deeply impoverished nation. With nothing in the way of employment waiting for them in Niger, these returnees may eventually pose a new security threat in Niger.

Niger is also having trouble hanging on to terrorists it has under detention; on June 1, 22 prisoners, including several convicted terrorists, were freed from a high-security prison in Niamey by three gunmen. One of those who escaped was Alassane Ould Muhammad “Cheibani,” a Gao region Arab with a history of prison escapes. Cheibani was serving a 20-year sentence for the December, 2000 assassination of William Bultemeier, a U.S. Embassy defense official in Niamey and the 2009 murder of four Saudi Arabians in northern Niger. Cheibani is also a prime suspect in the 2008 kidnappings of Canadian diplomats Robert Fowler and Louis Guay (RFI Online, June 4). [2]

Mali – Between Stabilization or a New War

In northern Mali’s Kidal region there is still no resolution to the differences between the Tuareg rebels of the Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA – a secular separatist movement) and the central government in Bamako. The situation is growing critical as Malian troops continue their slow progress towards Kidal, which they have announced they are determined to enter despite the MNLA’s promise to oppose their entry. Mahamadou Djeri Maiga, the vice-president of the MNLA’s political wing, has promised that: “If we are attacked, it will be the end of negotiations and we will fight to the end” (AFP, June 4).

With the Malian army looking for revenge against the MNLA and their supporters for the January 2012 massacre of Malian troops taken prisoner in Aguel Hoc, there are signs that renewed clashes are inevitable. Most notable of these indications was the heavy fighting between MNLA rebels and Malian government troops that took place near the village of Anefis on June 5. This time, the MNLA withdrew, but once they are pinned up against the Algerian border in Kidal they will have to choose between further resistance or the abandonment of their cause (and the consequences that will follow). The Malian troops, under the command of two of Mai’s most capable officers, Colonel Didier Dacko and Colonel Hajj ag Gamou, were accompanied by roughly 100 French troops, though it was uncertain whether they were there to aid the Malian army or to impede the outright defeat of the MNLA, which worked closely with French forces in finding and destroying Islamist elements hiding in the Idar des Ifoghas mountains.

A Malian government spokesman denounced what he described as “ethnic cleansing” in Kidal on June 4, promising that Malian troops would enter Kidal soon (L’Essor [Bamako], June 4). The charge of “ethnic cleansing” was in response to the MNLA’s arrest of dozens of Black Malians (mostly Peul/Fulani and Songhai) in Kidal during a hunt for “infiltrators” sent to the city by Malian military intelligence (RFI , June 3; AFP, June 3). Tensions in the city were reflected in a suicide bomber’s attempted assassination on June 4 of an MNLA colonel believed to have close ties to the French military (AFP, June 4).

The MNLA and the Malian government are once more at the negotiating table in Ougadougou, with Bamako working from the position presented in a UN Security Council resolution that the MNLA must lay down its arms and allow the Malian military to enter Kidal in return for negotiations by the next president regarding the status of Azawad. The MNLA believes it has already made sufficient concessions by abandoning its demand for independence and accepting the July elections (RFI, June 8). There is internal pressure in Bamako to press the administration to carry on the return of the Malian army to Kidal. Malian members of parliament declared in early June that they would not participate in the July elections if the Malian army was not present in Kidal (Info Matin [Bamako], June 4). The High Council for the Unity of Azawad (HCUA), founded in Kidal on May 19, largely from former members of rebel groups, has joined the MNLA in presenting a single position in the Ouagadougou negotiations.

Tuareg negotiators have indicated they are ready to sign a document advanced by the Burkina Faso mediators that would allow Malian troops to enter Kidal in advance of the planned July elections, but Bamako’s representatives have indicated they have reservations about the agreement, which would see rebels be confined to cantonments with their weapons in return for a “special status” for Azawad (northern Mali – a term Bamako does not wish to see in the document). Bamako is seeking complete disarmament and the pursuit of the arrest warrants issued for many Tuareg rebel leaders accused of various crimes before and during the Islamist occupation of northern Mali (AFP, June 13).

General Jean-Bosco Kazura

General Jean-Bosco Kazura

The African troops currently deployed in Mali are expected to be absorbed in several months by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), a 2,600 man force under the command of General Jean-Bosco Kazura of Rwanda, with a second-in-command from Niger and a French chief-of-staff. Though Chad was looking to take command of the mission, a poor interview by the Chadian candidate for command appears to have precluded this possibility and with it, the possible participation of Chadian forces (RFI, June 11). Additional troops may come from China, Bangladesh, Burundi, Honduras, Norway and Sweden, with a 1,000 man French rapid reaction force (Jeune Afrique, June 13).

Conclusion

Chadian president Idriss Déby has warned of the threat posed by terrorist groups now based in southern Libya, not only to his own country, but also to Europe, and has called for an international intervention to enable Libya to form a secure and functioning state that is not a threat to its neighbors. There is a danger of seeing this struggle as consisting of several different theaters defined by national boundaries, when this is contrary to the jihadist conception of this conflict, which is essentially borderless. AQIM, which was once largely restricted to activities within northern Algeria, has expanded into a number of related movements with operatives in Mauritania, Mali, Niger, and Libya and the potential to ally with other groups such as Boko Haram and Ansar al-Shari’a. With their mobility restored, the Islamist Jihadists of the Sahel/Sahara will continue to take advantage of regional political rivalries, under-equipped militaries and fears of neo-colonialism to rebuild their movement. Libya’s inability to secure its restless south and its readiness at the highest levels of government to ignore terrorist infiltration present the most immediate and most important challenges in restricting jihadist operations. Unless real international security cooperation can be established, the Islamist extremist groups may soon emerge with the upper hand in the struggle for the vast territories of northern Africa.

Notes

- For the attacks in Arlit and Agadez, see Andrew McGregor, “Niger: New Battleground for North Africa’s Islamist Militants?, Jamestown Foundation Hot Issue, May 29, 2013, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/hotissues/single-hot-issues/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=40932&tx_ttnews[backPid]=61&cHash=7c12e2e7bda14085101f67dc09adf5fa

2. U.S. Embassy Bamako Cable 09BAMAKO106, February 23, 2009.

This article was first published in the June 14, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor