Andrew McGregor

Countering Terrorism Center Sentinel

Volume 9, Issue 5 (May 2016)

West Point, N.Y.

Abstract: If the security situation in Libya deteriorates and the Islamic State makes further gains on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, there is the possibility that a coalition of foreign powers will feel compelled to intervene militarily. While such an intervention would likely be focused on the coastal regions, it would also likely have unforeseen consequences for southern Libya, a strategically vital region that supplies most of the country’s water and electricity. Militants could react by targeting this infrastructure or fleeing southward, destabilizing the region. For these reasons it is imperative that policymakers understand the strategic topography of southern Libya.

The Islamic State has succeeded in establishing a base in Sirte, Libya, on the Mediterranean coast, uncomfortably close to Europe. Unless a new government can unite the nation in deploying state security forces to eliminate the threat posed by the Islamic State, Ansar al-Sharia, and other extremist groups, there is a possibility of foreign military intervention. In this case, extremists could target the lightly guarded oil and water infrastructure in southern Libya essential for the survival of the nation.

The Islamic State has succeeded in establishing a base in Sirte, Libya, on the Mediterranean coast, uncomfortably close to Europe. Unless a new government can unite the nation in deploying state security forces to eliminate the threat posed by the Islamic State, Ansar al-Sharia, and other extremist groups, there is a possibility of foreign military intervention. In this case, extremists could target the lightly guarded oil and water infrastructure in southern Libya essential for the survival of the nation.

Bitter and bloody tribal conflicts have erupted in the south since the 2011 Libyan Revolution, and in the absence of state authority, various militias established their own version of security and border controls. There is a strong danger of further violence in the south spreading to Libya’s southern neighbors or encouraging new independence movements. Identifying specific strategic locations in southern Libya, this article outlines the security challenges posed in each locale by virtue of its geography as well as its ethnic, political, and sectarian rivalries.

Until recently, the inability of Libya’s rival governments—the Tripoli-based General National Council (GNC) and the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR)—to cooperate on the terrorism file has hampered the ability of foreign governments to provide military assistance. It has impeded Libya’s ability to tackle Islamist extremist movements as well, but this is beginning to change due to growing support for a unified Government of National Accord. [1]

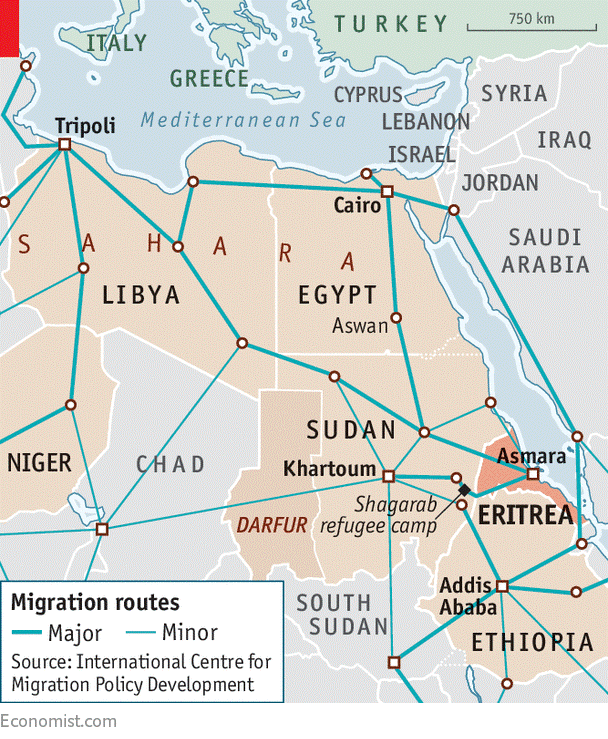

Libya-based terrorist groups are mainly concentrated in the Mediterranean coastal strip, but they have recognized the importance of Libya’s southern interior and the vast reserves of energy and water vital for Libyan viability. Control of the south determines whether the lights go on in Tripoli or Benghazi, whether water runs from the taps, and whether salaries are paid or not. It also means control of important trade and smuggling routes, the source of narcotics, armed militants, and waves of desperate African refugees risking their lives to reach Europe.

Currently, there are indications that France, Italy, the U.K., and the United States have either initiated limited interventions in the form of small Special Forces units or are contemplating greater military involvement to destroy Libya’s Islamic State group and end the uncontrolled movement of refugees to Europe from the Libyan coast. [2] In March the United Nations’ special envoy to Libya, Martin Kobler, warned Libyans that if they do not quickly address the problems of terrorism presented by Islamist extremists, “others will manage the situation.” [3] However, Libyans’ bitter experience with colonialism makes them highly suspicious of the motives behind any type of foreign intervention.

Geographic Considerations

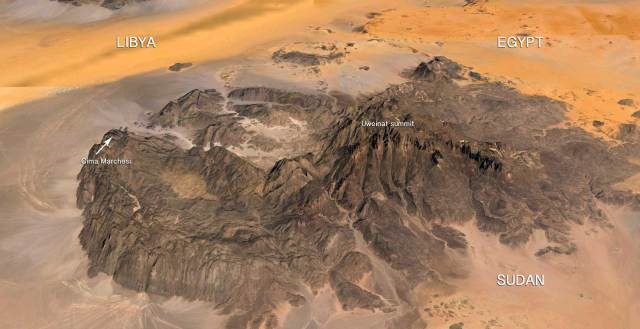

Libya is composed of three main regions: Tripolitania (the northwest), Cyrenaïca (the eastern half), and Fezzan (the southwest). Most of Libya’s water and energy resources are found in the south, an area of rocky plateaus known as hamadat and sand seas (ramlat), all punctuated with small oases and brackish lakes. Mountainous areas include the Tadrart Acacsus near Ghat in the Fezzan, the Bikku Bitti Mountains along the Chadian border, and Jabal Uwaynat in the southeast. The climate is exceedingly hot and arid with an average temperature of over 30 degrees Celsius; dry river beds known as wadis carry away the limited rainfall and are commonly used to conceal the movements of military or smuggling convoys. Sandstorms and high winds are common in March and April. The severe climate and isolation of Saharan Libya make it difficult to find security personnel from the north willing to serve there.

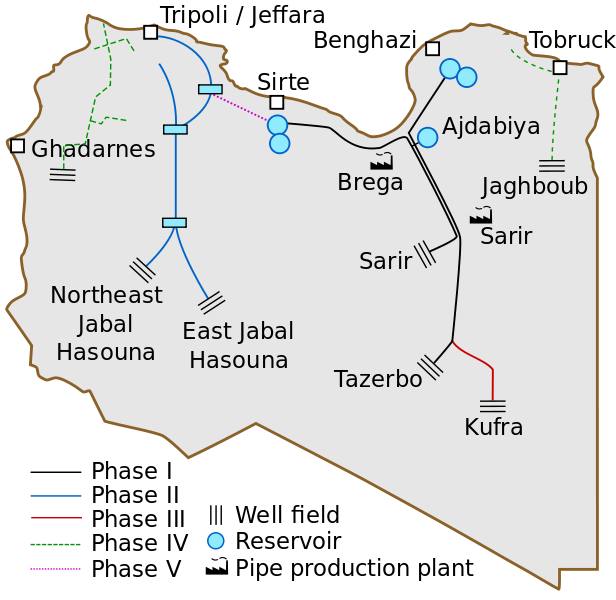

A Qaddafi initiative, the Great Man-Made River (GMR) taps immense reserves of fossil water (water trapped underground for more than a millennium) contained in the Nubian Sandstone aquifer under the Libyan desert to supply Libya’s coastal cities and various agricultural projects. GMR pipelines are vulnerable to tribal groups angered by government activities. [4]

There are five energy basins (regions containing oil and gas reserves) in Libya: Ghadames/Berkine (northwest); Sirte, the most productive (central); Murzuq (southwest); Kufra (southeast); and the Cyrenaïca platform (northeast). Of these, only the Kufra Basin is not yet in production. [5]

Libya’s oases provide water and resting points in a strategic lifeline through otherwise inhospitable terrain and permit overland contact between the settlements of the Mediterranean coast and the African interior. Today, oil and water pipelines follow these routes, giving them even greater importance in the modern era.

The Tribal Situation

The southern Arabs fear that post-revolutionary demands for citizenship by non-Arab Tubu and Tuareg will make citizens of tens of thousands of non-Arabs from outside Libya’s borders, leaving the Arabs a minority in the region. The Tubu and Tuareg, in turn, fear they are victims of Arab machinations to cleanse Libya of non-Arab groups. The Tubu, an indigenous African group, are found in Chad, northeastern Niger, and southern Libya, with a traditional stronghold in the remote Tibesti mountain range of northern Chad.[6] The Tuareg are an indigenous Berber group organized in various confederations and spread through much of the Sahara/Sahel region, where they traditionally maintained control of trans-Saharan trade routes. In Libya the local Tuareg live in the southwest and are part of the Kel Ajjar confederation also found in eastern Algeria.

Strategic Sites in Southern Libya

In April 2014, French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian described southern Libya as “a viper’s nest in which jihadists are returning, acquiring weapons and recruiting.”[7] Through Ottoman and Italian colonial rule, southern Libya provided a place of refuge for political, tribal, and religious groups that came into conflict with the established powers. More recently, it has offered operating space to extremist groups forced from neighboring areas such as northern Mali. With the development of Libyan plans to assault the Islamic State enclave in Sirte and the possibility of foreign military intervention at some point in the future if those efforts fail, it is worthwhile to examine those strategic sites in southern Libya that might provide new bases for Islamist extremists or those forces involved in combating such movements

The Ottoman/Italian Fortress in Ghat on Koukemen Hill

The Ottoman/Italian Fortress in Ghat on Koukemen Hill

Ghat

As a garrison town on the Algerian border and a center for Qaddafi loyalists, Ghat was one of the last urban areas in Libya to fall to rebel forces in late September 2011. Dotted throughout southern Libya are Ottoman and Italian fortresses, built on heights wherever possible to control important oases or the intersection of vital trade routes; many of these now serve as bases for regional militias. In Ghat, Tuareg militias hold the large Ottoman fortress on the Koukemen Hill finished by the Italians in the 1930s. There is also an airport 18 kilometers north of Ghat. The Ghat Tuareg control the Tinkarine border crossing into Algeria. Control of this crossing in the event of a foreign intervention would be essential to prevent cross-border movement of extremist groups. The Algerian Army closed the border with Libya in May 2014 after the In Amenas attacks, which originated in al-Uwaynat (not to be confused with al-Uwaynat in southeastern Libya), northeast of Ghat.[8]

Italian-era Fortress at Zillah, al-Jufra

Italian-era Fortress at Zillah, al-Jufra

Hun

Hun is the main town in al-Jufra oasis and a former colonial base for long-range patrols by the Italian Compagnia Sahariana. Other settlements in al-Jufra include Waddan, site of a pre-Ottoman Arab fortress; Sokna, the site of an Ottoman castle; Zellah Oasis, which is overlooked by a massive Italian-era hilltop fortress; and al-Fugha, a small oasis devoted, like the others, to date production. Al-Jufra Airbase is a dormant Libyan Air Force facility.

Jalu and Awjala

These oases are not in southern Libya proper, but they form an important link on the Kufra-Ajdabiya road and an entry point to the string of oases in Egypt’s Western Desert, a suspected route for arms traffickers. The town of Jalu, an important center for nearby oil fields, is located some 250 kilometers southeast of the Gulf of Sidra, while Awjala is about 30 kilometers northwest of Jalu. Jalu proved its strategic importance in both World War II and the Libyan Civil War during attempts to outflank opposing forces operating closer to the coast. Its size (19 kilometers by 11 kilometers) and freshwater supplies made it a useful base for military operations. As the dominant group in both oases is Eastern Berber, there is a possibility that ethnic tensions could be inflamed by renewed military activity in this strategically vital locale.

Kufra

The town of Kufra and a surrounding cluster of small oases and agricultural projects have a population of roughly 40,000. Its strategic importance lies in its location between two sand seas, which, with its reserves of fresh water and food, make it an inevitable stop for vehicles making their way between the Cyrenaïcan coast and the African interior.

Zuwaya Arabs are the majority in Kufra, which has a Tubu minority. Both the Tubu and the Zuwaya maintain important communities in Ajdabiya charged with protecting tribal interests at the northern terminus of the trade route from Kufra. Should conflict erupt between these communities as a consequence of foreign military activity in the Ajdabiya region, the result could easily be the spread of communal clashes to the volatile Kufra area.

The route between Kufra and Ajdabiya was the site of numerous skirmishes between Qaddafi loyalists and Libyan rebels during the civil war, with the Qaddafists carrying out a long-range desert attack to seize Kufra before working their way north to the Jalu and Awjala oases, where efforts were made to damage water and oil installations.[9] The limited cooperation between revolutionary Tubu and Zuwaya against the Qaddafi regime did not last, with the Zuwaya describing the Tubu as Qaddafist collaborators or even foreign mercenaries. In 2012, the Zuwaya constructed large sand berms around Kufra to cut Tubu connections with the outside.

Disputes over control of smuggling and trading routes south of Kufra led to clashes between Tubu and Zuwaya in 2011, 2012, and 2013 that left hundreds dead. Mediation brought an end to a further two months of fighting in early November 2015. Isa Abd al-Majid Mansur, leader of the Tubu Front for the Salvation of Libya (TFSL), has promoted the idea of foreign intervention in Libya, suggesting the Tubu would make good partners in international counterterrorism and anti-smuggling operations.[10] While seemingly attractive given the Tubu’s deep knowledge of the little-known region, acceptance would immediately be viewed as unacceptable by rival Arab groups and inevitably regarded as a means of challenging the “Arab essence” of the Libyan state.

The construction of the Trans-Saharan road connecting Darfur to Kufra in the 1980s increased cross-border trade but also opened a reliable route for smugglers, human traffickers, and gunmen. Qatar appears to have used the route from Sudan to ship ammunition to Islamist militias in 2011.[11]

Darfur rebels of the Sudanese Liberation Movement-Minni Minnawi (SLM-MM) were accused by the GNC and the Sudanese government of collaborating with Tubu forces under the direction of General Khalifa Haftar in the unsuccessful September 20, 2015, attack on Kufra.[12] The SLM-MM and Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) were accused of committing armed robberies and setting up illegal checkpoints north of Kufra this year before being driven out by Zuwaya militias in a two-day battle in February.[13] On April 24, 2016, Libya’s new Presidency Council announced it had received information that JEM was collaborating with Qaddafi loyalists to attack and disrupt oil facilities in southern Libya.[14] Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) has repeatedly accused Khartoum of shipping arms and fighters to Islamist groups by air and by the overland route through Kufra.[15]

Ma’atan al-Sarra

Ma’atan al-Sarra Oasis is located in the Kufra district some 60 miles north of the border with Chad. Qaddafi used the remote and rarely visited oasis as a supply base for Sadiq al-Mahdi’s 1976 attack on Khartoum. In the 1987 “Toyota War,” Chadian forces (mostly Tubu) took Ma’atan al-Sarra in a devastating surprise attack.

Ottoman-era Fortress, Murzuq

Ottoman-era Fortress, Murzuq

Murzuq

Murzuq, the unofficial “headquarters” of the Fezzan Tubu, is 150 kilometers south of Sabha. Murzuq, like Ubari, lies on the southwest to northeast route that separates the Ubari and Murzuq sand seas. Murzuq is populated by a potentially volatile mix of Tuareg, Tubu, Arabs, and al-Ahali (black Libyans descended from slaves or economic migrants from the African interior), with each community ready to exploit or reject foreign intervention in light of their own interests.

The head of the Murzuq Military Council, Colonel Barka Wardougou, a Libyan Army veteran with experience in Chad and Lebanon and the former leader of a Tubu rebel goup in Niger that joined Niger’s 2007-2009 Tuareg rebellion, has demanded a more equitable distribution of Libya’s oil wealth, threatening to form a federal state if this is not accomplished.[16]

Qatrun

The road south from Murzuq runs through the oasis town of Qatrun, where it splits to run 310 kilometers southwest to the border post with Niger at Tummo, and southeast toward Chad. When the border post at Tummo is closed, travelers from Niger must report to Libyan authorities in Qatrun. The Tubu and Qaddadfa Arabs have a strong presence in the area.

Rabyanah Oasis and Sand Sea

On the western side of the southern route to Kufra is the inhospitable Rabyanah Sand Sea. Toward the eastern end of this feature is the Tubu-dominated Rabyanah Oasis, 130 kilometers west of Kufra, and the home district of several leading Tubu militia and political leaders as well as a Zuwaya minority. In the event of a foreign intervention, this region could provide a base for the development of new Tubu political factions.

Elena Castle, Sabha

Elena Castle, Sabha

Sabha

Sabha, 500 miles south of Tripoli, is the site of an important military base and airfield. The city of 210,000 people acts as a commercial and transportation hub for the region. During the Qaddafi era, the oasis was used for the development of rockets and nuclear weapons. Sabha is a tinderbox of rival ethnic/tribal communities, including the Arab Qaddadfa, their Awlad Sulayman rivals, Warfalla and Magraha Arabs, Tubu, and Tuareg. According to one Tubu leader, Sabha also serves as a local collection center for al-Qa`ida fighters from Mauritania, Libya, Algeria, and Tunisia.[17] If foreign extremists have already established a presence in Sabha, it would take very little to provoke new clashes that would further destabilize this important region.

Sabha’s Elena Castle under fire, January 2014

Sabha’s Elena Castle under fire, January 2014

The revolutionary Awlad Sulayman and the loyalist Qaddadfa confronted each other during the civil war despite a tribal alliance.[18] The largest Awlad Sulayman militia seized Sabha’s airport from a Hasawna Arab militia in September 2013.[19] Clashes between the Tubu and members of the Arab Awlad Abu Seif and Awlad Sulayman tribes in March 2012 killed at least 100 people. By June the Tubu were clashing with the Libyan Shield Brigade that had been sent to restore order. The Tubu and the Awlad Sulayman set upon each other again in 2013 and 2014, while the Qaddadfa Arabs and the Awlad Sulayman clashed in 2012, 2013, and 2014.[20] By July 2015, the Sabha Tubu were involved in new clashes with both Tuareg and Qaddadfa and demanding the expulsion of Awlad Sulayman fighters from Sabha’s Italian-era Elena castle (the former Fortezza Margherita).[21]

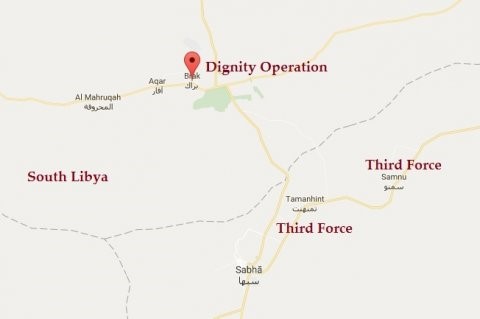

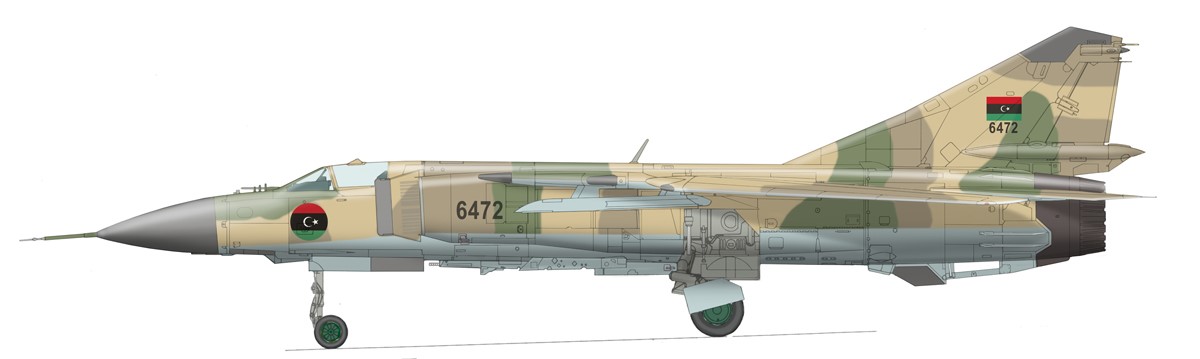

Tamenhint airbase, 30 kilometers northeast of Sabha, allowed Qaddafi to project air power into the Sahel and was an important operational base during the conflicts in Chad. The base was occupied by alleged “Qaddafists” in January 2014 who were driven out by government airstrikes and Tubu ground forces, though fighting continued for several days north of Tamenhint.[22]

Salvador Pass

The Salvador Pass lies at the north end of the Manguéni Plateau near the meeting point of Algeria, Niger, and Libya. Remote and unsupervised, the narrow mountain pass is used by well-armed traffickers and rebels to avoid the official crossing at Tummo.[23] Most notable of these is al-Murabitun leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar, who is believed to have used the Pass to flee from French-led forces in early 2013.[24] On the Libyan side, the Pass is nominally held by Tuareg militias that are often reduced to sending in reports of illegal crossings when they are outgunned. In mid-April 2015, the French 2e Régiment étranger de parachutistes (2e REP) met with a detachment of the Nigerien Army and consolidated control of the Pass.[25]

Sarir

The Sarir oil fields (400 kilometers south of Ajdabiya) are among Libya’s most productive and were the scene of heated struggles for control between Qaddafi loyalists and Tubu revolutionaries during the 2011 rebellion. There have since been repeated attacks on the Sarir power station and other facilities, the latest in mid-March 2016 when a suicide bomber and gunman believed to be affiliated with the Islamic State were killed by the Tubu 25th Brigade, affiliated with the Petroleum Facilities Guard (PFG). Other gunmen escaped after damaging power lines, pipelines, and Great Man-Made River facilities.[26] Clashes between Zuwaya gunmen and Tubu guards in 2013 and 2014 caused power shortages in Benghazi and Tripoli.[27]

Hundreds of Tubu fighters from the 25th Brigade and others from the Desert Shield and Martyrs of Um Aranib militias in southwest Libya headed north to Benghazi to join the LNA in their campaign against Islamist groups in Benghazi in 2014.[28] Foreign intervention in Libya could compel these forces to return south to protect local interests with a subsequent reduction of experienced fighters available to combat extremist groups in the north.

Sharara

In the desert outside of Murzuq, 70 kilometers west of Ubari, is the Sharara oil field, Libya’s largest. The area has been the scene of fighting between Tuareg and Tubu groups with production halted repeatedly by armed protesters seizing facilities to press various demands.[29] Al-Sharara and the neighboring al-Fil oil field are guarded by a Tubu-dominated detachment of the PFG that includes Zintanis and a number of Tuareg and Arabs. The PFG shut down al-Fil for a month over unpaid salaries in May-June 2014.[30]

In November 2014, a Tuareg militia attacked Zintani members of the PFG, closing the field and depriving Libya of a third of its production. The Misratan 3rd Force operating out of Tamenhint Airbase joined forces with local Tuareg fighters and retook Sharara on November 7, 2014.[31]

Tazirbu

This group of 14 small oases, located roughly 250 kilometers northwest of Kufra, was formerly the seat of the Tubu Sultan, though the Zuwaya now dominate. Its importance today lies in the 120 wells just south of Tazirbu that pump aquifer water to Benghazi and Sirte through the GMR.

Tummo Pass

South of the Plateau du Manguéni is the Tummo Pass, the official but rarely attended border post between Niger and southwest Libya. In Niger, some 80 kilometers south of the Tummo Pass, French Legionnaires and Nigerien troops have set up a forward operating base and airstrip to conduct surveillance and interception operations at Fort Madama, a colonial-era French fort.[32] Like the Salvador Pass, control of this crossing would be essential to prevent the entry or escape of extremist groups in the event of a foreign intervention, though the French presence has gone a long way to secure the Pass.

Damage suffered to Ubari’s Ottoman-era Castle during fighting in January 2016

Damage suffered to Ubari’s Ottoman-era Castle during fighting in January 2016

Ubari

A town of 40,000 people, Ubari is in the Targa valley, 200 kilometers west of Sabha. The Tuareg majority were generally cordial with the Arab and Tubu minorities until the arrival of a Libya Dawn-affiliated Tuareg militia from outside the area in 2014. Local Tuareg who had refused to join the group were nevertheless pulled into the fighting when the militia clashed with armed Tubu groups, splitting the town into two parts. After a year of fighting and hundreds of deaths, a peace agreement ended 14 months of conflict in November 2015, but sporadic clashes continue.[33]

The latest of these involved bombardments by Tuareg occupying the Tendi Mountain high ground that damaged Tubu neighborhoods and Ubari’s historic Ottoman castle (now used as a fort by Tubu fighters).[34]

A former military compound in Ubari is used as a base for the Border Guards Brigade 315, an Islamist militia led by Tuareg Salafist scholar and former Ansar al-Din deputy commander Ahmad Omar al-Ansari who operates a religious school in a slum area of Ubari.[35] Brigade 315 serves simultaneously as a border guard and an alleged conduit for extremists crossing into Libya.[36]

Al-Uwaynat

Al-Uwaynat is a mountain complex of 1,200 square kilometers situated at the meeting point of Libya, Egypt, and Sudan and is best known for several small springs in the midst of an otherwise waterless desert. During the Libyan revolution, Sudan set up a military support base for the Libyan rebels at Uwaynat.[37] Today, the route has been revived for commercial traffic, smuggling, human trafficking, tourist expeditions, and the movement of armed groups. Sudan has long feared the entry of al-Qa`ida or Islamic State groups into the unstable Darfur region through this route and would almost certainly bring strong forces into the area to prevent the infiltration of radical Islamists seeking to escape a foreign military intervention in Libya.

Al-Wigh Air Force Base

Strategically located close to the borders with Niger, Chad, and Algeria, al-Wigh is currently held by the Tubu Um al-Aranib Martyrs’ Brigade. In 2013, Prime Minister Ali Zidan rejected rumors al-Wigh was being used for French Special Forces operations or as a base for terrorist operations in Algeria.

Southern Libya’s Borders

Libya’s southern borders include those with Algeria (982 kilometers), Chad (1,055 kilometers), Sudan (383 kilometers), and Niger (354 kilometers). Most of the southern tribes have benefitted slightly, if at all from Libya’s enormous oil wealth, leading to competition over the cross-border smuggling trade that often takes on ethnic or tribal overtones. Sudan and Libya created a joint border patrol in 2013, but Libya pulled out of the joint patrols in the summer of 2015.[38] In the absence of government authority, control of Libya’s southern borders has been divided between Tubu and Tuareg militias. In the west, the Tuareg control the borders with Algeria and Niger as far as the Tummo border crossing; past that the borders with Niger, Chad, and Sudan are controlled by the Tubu as far as Jabal Uwaynat.[39]

Whether Tuareg or Tubu, border patrols in the south are unfunded by Libyan authorities. As a consequence, the patrols claim to focus on “social evils,” such as arms, narcotics, and militants, allowing fuel, subsidized food, cigarettes, and illegal migrants to pass for a fee. Tubu patrols on the western border complain that they receive no response from government authorities when they report terrorist infiltrations, resulting in easy entry to Southen Libya for jihadist groups operating in the Sahel/Sahara region.[40]

Conclusion

A limited deployment in northern Libya could easily trigger violence in southern Libya that would destabilize the nation as a whole through the uncontrolled infiltration of extremists through a region already notorious for a perilous combination of vital economic installations and a general absence of security. Foreign intervention in a region historically hostile to foreign rule and where the state is already regarded as weak and unsympathetic to local aspirations could also encourage southern separatism. Various groups in the south have pondered the possibility of independence, namely the Tubu centered around Kufra, the Tuareg in the southwestern border regions, and some Arab factions in the Fezzan, alarming Libya’s southern and western neighbors where such movements have been active for decades.

A January Islamic State video statement threatened attacks on “al-Sarir, Jalu, and al-Kufra,”[41] but religious extremism has so far played only a small role in southern Libya’s political and ethnic violence. Porous borders present the possibility of Libya’s south acting as a gateway for jihadis from the Sahara/Sahel to pour into Libya to confront a foreign intervention, while Islamic State fighters might move south from Sirte in the event of an intervention, either with the intention of attacking vital installations, connecting with other Islamist groups in Libya’s southwest, or escaping into the Sahel.

Until the establishment of a representative unity government in Tripoli with the ability to deploy recognized national security units instead of ethnically or regionally based militias, vital southern oil and water infrastructure will present an enticing target for attacks by terrorists, rebels, or criminal organizations.

Dr. Andrew McGregor is the director of Aberfoyle International Security, a Toronto-based agency specializing in the analysis of security issues in Africa and the Islamic world.

Citations

[1] “Majority of HoR members declare approval of national unity government but want Article 8 deleted,” Libya Herald, April 21, 2016.

[2] Missy Ryan and Sudarsan Raghavan, “Another Western Intervention in Libya Looms,” Washington Post, April 3, 2016; “France says be ready for Libya intervention,” Agence France-Presse, April 1, 2016; Mark Hookham and Tim Ripley, “SAS adds steel to Libya’s anti-Isis militias,” Sunday Times, April 17, 2016; Nathalie Guibert,”La France mène des opérations secrètes en Libye,” Le Monde, February 24, 2016; Daniele Raineri, “Esclusiva: una manciata di Forze speciali italiane è in Libia, Il Foglio, December 3, 2015; “Libia: dai parà agli incursori, le forze speciali italiane,” Agenzia Giornalistica Italia, March 4, 2016.

[3] “Presidency Council must go ‘very quickly’ to Tripoli and rebuild army for battle against IS: if not, ‘others’ will carry out the fight: Kobler,” Libya Herald, March 22, 2016.

[4] Seraj Essul and Elabed Elraqubi, “Man-Made River Cut: Western Libya could face water shortage,” Libya Herald, September 3, 2013; “Libya ex-spy chief’s daughter Anoud al-Senussi released,” BBC, September 8, 2013.

[5] Sebastian Luening and Jonathan Craig, “Re-evaluation of the petroleum potential of the Kufra Basin (SE Libya, NE Chad): Does the source rock barrier fall?” Marine and Petroleum Geology 16:7 (November 1999): pp. 693-718; U.S. Department of Energy, “Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: Libya,” September 2015; Omar Badawi Abu-elbashar, “Recent Exploration Activities in NW Sudan Reveal the Potential of South Kufra Basin in Chad,” American Association of Petroleum Geologists European Region’s 2nd International Conference held in Marrakech, Morocco, October 5-7, 2011.

[6] For more on tribal dynamics in southern Libya, see Geoffrey Howard, “Libya’s South: The Forgotten Frontier,” CTC Sentinel 7:11 (2014).

[7] John Irish, “France says Southern Libya now a ‘viper’s nest’ for Islamist militants,” Reuters, April 7, 2014.

[8] Wolfram Lacher, “Libya’s Fractious South and Regional Instability,” Small Arms Survey Dispatch no. 3, February 2014.

[9] “Gaddafi Attack on Libyan Oasis Town,” Agence France-Presse, May 1, 2011.

[10] “Libya’s Toubou tribal leader raises separatist bid,” Agence France-Presse, March 27, 2012.

[11] Sam Dagher and Charles Levinson, “Tiny Kingdom’s Huge Role in Libya Draws Concern,” Wall Street Journal, October 17, 2011.

[12] “Khalifa Haftar-linked Darfur rebels are behind Al-Kufra attack, official sources confirm,” Libya Observer, September 23, 2015; “Al-Kufra Clashes,” Libyan Observer, September 20, 2015.

[13] “Heavy clashes in southeast Libya, 30 killed,” Reuters, February 6, 2016; “Clashes in Libya: Sudan, Darfur rebels exchange accusations,” Radio Dabanga, February 12, 2016; “Ten more Darfur rebels killed in Libya,” Sudan Tribune, February 6, 2016; “SLM-Minnawi denies clashes in southern Libya,” Sudan Tribune, February 7, 2016.

[14] Ajnadin Mustafa, “Sewehli tells Serraj to liberate Sirte as Haftar gathers forces and Presidency Council warns of possible IS oilfield attacks,” Libya Herald, April 25, 2016.

[15] “Dignity commander claims Ansar and Libyan Brotherhood linked to ISIS,” Libya Herald, September 29, 2014; “Sudan denies arms being shifted between Darfur and Libya,” Sudan Tribune, March 8, 2015.

[16] “Three killed by Qaddafi sympathisers in Revolution Day clashes in Sebha,” Libya Herald, February 17, 2016.

[17] François de Labarre, “Le chef des Toubous libyens le promet ‘Nous combattons Al Qaïda,’” Paris Match, January 20, 2014.

[18] Lacher.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Jamal Adel and Seraj Essul, “Fresh communal clashes in Sabha,” Libya Herald, June 2, 2014.

[21] Mustafa Khalifa, “Four killed in further Tebu-Tuareg clashes in Sebha,” Libya Herald, July 13, 2015.

[22] Jamal Adel, “Libya: Fighting between Misratan forces and Qaddafi supporters at Sebha airbase,” Libya Herald, January 23, 2014; Jamal Adel, “Tamenhint airbase remains under Qaddafi loyalist control as Sebha clashes continue,” Libya Herald, January 23, 2014.

[23] Yvan Guichaoua, “Tuareg Militancy and the Sahelian Shockwaves of the Libyan Revolution,” in Peter Cole and Brian McQuinn eds., The Libyan Revolution and its Aftermath (London, U.K.: Hurst, 2014), p. 324.

[24] Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, “Video shows return of jihadist commander ‘Mr. Marlboro’,” CNN, September 11, 2013; “Extremists flock to Libya’s Salvador Pass to train,” Agence France-Presse, October 27, 2014.

[25] Video of the drop taken by a Harfang drone is available on YouTube. See also Andrew McGregor: “French Foreign Legion Operation in the Strategic Passe de Salvador,” Tips and Trends: The AIS African Security Report, May 30, 2015.

[26] “AGOCO officials inspect Sarir damage, pay respect to victims,” Libya Herald, March 21, 2016.

[27] “Attack on Sarir power station: report,” Libya Herald, March 14, 2016.

[28] Jamel Adel, “Tebu troops head to Benghazi to reinforce Operation Dignity,” Libya Herald, September 10, 2014.

[29] “Libya’s El Sharara oilfield ‘shut in,’” Reuters, November 6, 2014.

[30] Jamal Adel, “Production stops at El Fil oilfield,” Libya Herald, November 9, 2014.

[31] Jamal Adel, “Production at Sharara oilfield collapses following attacks,” Libya Herald, November 6, 2014; Jamal Adel, “Sharara oilfield taken over by joint Misratan/Tuareg force,” Libya Herald, November 8, 2014; Saleh Sarrar: “Libya’s Biggest Oil Field to Resume Pumping by Tomorrow,” Bloomberg News, November 9, 2014.

[32] Video of 2e REP in the Salvador Pass is available on YouTube.

[33] “Tebu and Tuareg sign peace deal in Qatar to end Ubari conflict,” Libya Channel, November 25, 2015.

[34] “Historic Obari castle damaged in renewed Tebu-Tuareg fighting,” Libya Herald, January 12, 2016; “More deadly fighting in Obari,” Libya Herald, January 15, 2015.

[35] Mathieu Galtier, “Southern borders wide open,” Libya Herald, September 20, 2013; Rebecca Murray, “In a Southern Libya Oasis, a Proxy War Engulfs Two Tribes,” Vice News, June 7, 2015.

[36] Nicholas A. Heras, “New Salafist Commander Omar al-Ansari Emerges in Southwest Libya,” Jamestown Foundation Militant Leadership Monitor 5:12 (December 31, 2014).

[37] Rebecca Murray, “Libya’s Tebu: Living in the Margins,” in Peter Cole and Brian McQuinn eds., The Libyan Revolution and its Aftermath (London, U.K.: Hurst, 2014), p. 311.

[38] “Sudanese army says Libya pulled out its troops from the joint border force,” Sudan Tribune, August 2, 2015.

[39] Jamil Abu Assi, “Libye: Panorama des Forces en Présence,” Bulletin de Documentation N°13, Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement, March 13, 2015.

[40] Maryline Dumas, “La situation des frontières au sud est toujours critique,” Inter Press News Services Agency, September 13, 2014.

[41] Ayman al-Warfalli, “Militants attack storage tanks near Libya’s Ras Lanuf oil terminal,” Reuters, January 21, 2016.

LNA Forces seize Jufra Airbase in June, 2017 (Libya Express)

LNA Forces seize Jufra Airbase in June, 2017 (Libya Express)