Andrew McGregor

September 16, 2011

At least 1,500 Tuareg fighters joined Muammar Qadaffi’s loyalist forces (though some sources cite much larger figures) in the failed defense of his Libyan regime. Many were ex-rebels residing in Libya, while others were recruited from across the Sahel with promises of large bonuses and even Libyan citizenship. Many of the Tuareg fighters are now returning to Mali, Niger and elsewhere in the Sahel, but for some the war may not yet be over; there are reports of up to 500 Tuareg fighters having joined loyalist forces holding the coastal town of Sirte, Qaddafi’s birthplace and a loyalist stronghold (AFP, September 3; September 5).

Tuareg Regions of North Africa

The Regional Dimension of the Libyan Regime’s Collapse

Media in the Malian capital have warned that the “defeated mercenaries” are back from Libya with heavy weapons and lots of money to prepare a new Tuareg rebellion, labeling themselves “combatants for the liberation of Azawad” (Le Pretoire [Bamako], May 9). Mali has not yet recognized the Transitional National Council (TNC) as the new Libyan government; Mali’s reticence in recognizing the rebels as the new government in Libya may have something to do with the large investments made in Mali by the Qaddafi regime (L’Independant [Bamako], September 6). The Libyan leader has significant support in Mali and other parts of West Africa and a number of pro-Qaddafi demonstrations have been witnessed in Mali since the revolution began in February.

The new president of Niger, Mahamadou Issoufou, has warned of Libya turning into another Somalia, spreading instability throughout the region:

The Libyan crisis amplifies the threats confronting countries in the region. We were already exposed to the fundamentalist threat, to the menace of criminal organizations, drug traffickers, arms traffickers… Today, all these problems have increased. All the more so because weapon depots have been looted in Libya and such weapons have been disseminated throughout the region. Yes, I am very worried: we fear that there may be a breakdown of the Libyan state, as was the case in Somalia, eventually bringing to power religious extremists (Jeune Afrique, July 30).

Algeria has its own concerns, fearing that instability in the Sahara/Sahel will provoke further undesirable French military deployments or interventions in the region.

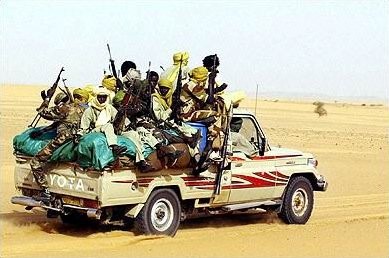

Convoys Out of Libya

Tuareg troops escaping from Libya have been observed using 4X4 vehicles to cross into Niger (El Khabar [Algiers], August 29).On September 5, it was reported that “an exceptionally large and rare convoy” of over 200 military vehicles belonging to the southern garrisons of the Libyan Army entered the city of Agadez, the capital of the old Tuareg-controlled Agadez sultanate that controlled trade routes in the region for centuries (Le Monde, September 6; AFP, September 6). A number of people reported seeing Tuareg rebel Rhissa Ag Boula in the convoy (Le Monde, September 6). Ag Boula was last reported to have been under arrest in Niamey after re-entering Niger in April 2010. Ag Boula mistakenly believed he was covered by a government amnesty against a death sentence passed in absentia for his alleged role in the assassination of a politician.

According to NATO spokesman Colonel Roland Lavoie, the convoy was not tracked by the concentrated array of surveillance assets deployed over Libya: “To be clear, our mission is to protect the civilian population in Libya, not to track and target thousands of fleeing former regime leaders, mercenaries, military commanders and internally displaced people” (AFP, September 6). In a campaign that has seen NATO target civilian television workers as a “threat to civilian lives,” it is difficult to believe that a heavily-armed convoy of 200 vehicles containing Qaddafi loyalists was of no interest to NATO’s operational command. There has been widespread speculation that the convoy contained some part of Libya’s gold reserves, which were moved to the southern Sabha Oasis when the fighting began.

Nigerien foreign minister Mohamed Bazoum initially denied the arrival of a 200 vehicle convoy in his country, but admitted that Abdullah Mansur Daw, Libya’s intelligence chief in charge of Tuareg issues, arrived in Niger on September 4 with nine vehicles (Le Monde [Paris], September 8; AFP, September 5). Daw was accompanied by Agali Alambo, a Tuareg rebel leader who has lived in Libya since 2009 and was cited as a major recruiter of hundreds of former Tuareg rebels in Niger. Alambo later described escaping south through the Murzuq triangle “and then straight down to Agadez” after his party learned the Algerian border was closed and the route into Chad was blocked by Tubu fighters who had joined the TNC (Reuters, September 11). Daw and Alambo reached Niamey on September 5 with an escort of Nigerien military vehicles. Libya’s TNC has promised it will request the extradition of leading Qaddafi loyalists from Niger (AFP, September 10).

General Ali Kana, a Tuareg officer commanding government troops in southern Libya, was reported to have crossed into Niger on September 9 with a force of heavily armed troops (Tripoli Post, September 9). A former spokesman for the Tuareg rebel group Mouvement des nigériens pour la justice (MNJ) said that Kana was considering defecting after having angered Libyan Tuareg by leading an attack on a Tuareg town in Libya in which several Tuareg were killed, and by recruiting Tuareg mercenaries from Mali and Niger but failing to pay them the huge sums of cash he was given by Qadaffi for the purpose (AP, September 9). Ali Kana was reported to be with Libyan Air Force chief Al-Rifi Ali al-Sharif and Mahammed Abidalkarem, military commander in the southern garrison of Murzuq (AFP, September 10).

Some Tuareg returning from the Libyan battlefields expressed disenchantment with their time in Libya, complaining they were not allowed to fight in units composed solely of Tuareg (AFP, April 21). Others have complained they were never paid; one fighter said he was part of a group of 229 Tuareg recruited by Agali Alambo with a promise of a 5,000 Euro advance, but had never seen a penny (AFP, September 3). Others did receive smaller payments and the offer of Libyan citizenship. One Tuareg fighter described being assigned to a Tuareg brigade that was later attached to Khamis al-Qaddafi’s 32nd Mechanized Brigade for battles in Misrata and elsewhere (The Atlantic, August 31).

Some Tuareg leaders in Niger and Mali are urging Tuareg regulars of the Libyan Army to rally to the rebel cause and remain in Libya rather than return to Niger and Mali with their arms but little chance of employment. The tribal leaders have set up a contact group with the TNC to allow Tuareg regulars to join the rebels without threat of reprisal in an attempt to ward off a civil war in Libya (Reuters, September 4, Radio France Internationale, August 23). “Niger and Mali are very fragile states — they could not take such an influx…” said Mohamed Anacko, the head of the Agadez regional council and a contact group member (Reuters, September 4). At the moment, however, crossing the lines to a disparate and undisciplined rebel army remains a dangerous proposition for Tuareg regulars closely identified with the regime.

The Tuareg may not be the only insurgents forced out of Libya; there are reports from Chadian officials that over 100 heavily armed vehicles belonging to Dr. Khalil Ibrahim’s Darfur-based Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) had crossed the Libyan border. Ibrahim had taken refuge in Libya after losing his bases in Chad to a Chadian-Sudanese peace agreement. JEM denied knowledge of the movement and also denied receiving weapons from Libya (AFP, September 9).

Libyan Tuareg

The Libyan Tuareg

Besides the West African Tuareg who rallied to Qaddafi, Libya is home to a Tuareg community of roughly 100,000 people, though the regime has never recognized them as such, claiming they are only an isolated branch of the Arab race. Though some Libyan Tuareg have opposed Qadaffi, many others have found employment in the Libyan regular army, together with volunteers from Mali and Niger. As a result, many Libyans tend to identify all Tuareg as regime supporters. Near the desert town of Ghadames local Tuareg were threatened by rebels seeking to expel them from the city before Algeria opened a nearby border post and began allowing the Tuareg to cross into safety on August 30 (Ennahar [Algiers], September 1; El Khabar [Algiers], September 5). Five hundred Algerian Tuareg were reported to have crossed into Algeria while the border remained open (Le Monde, September 8). Some of the refugees promised to settle their families in Algeria before crossing back into Ghadames with arms to confront the rebels (The Observer, September 2).

The Death of Ibrahim Ag Bahanga

The most prominent of the Tuareg rebel leaders, Ibrahim Ag Bahanga, was reported to have died in a vehicle accident in Tin-Essalak on August 26 after having spent most of the last two years as an exile in Libya (Tout sur l’Algérie [Algiers], August 29). [1] It was widely believed in Mali that Ag Bahanga was preparing a new rebellion with weapons obtained from Libyan armories (Nouvelle Liberation [Bamako], August 17; Ennahar [Algiers] August 27).

He was reportedly buried within hours, preventing any examination of the cause of death despite some reports his body showed signs of having been shot repeatedly. Some claim that Ag Bahanga was actually killed by other Tuareg in a dispute over weapons, though others in Mali have suggested the Tuareg rebel leader was killed by a landmine or even a missile after his Thuraya cell phone was detected by French intelligence services, though it seems unlikely the veteran rebel would make such a mistake (L’Indépendant [Bamako], August 30; Le Pretoire [Bamako], September 6; Info Matin [Bamako], August 29). Despite Ag Bahanga’s resolute opposition to the Malian regime, President Ahmadou Toumani Touré was reported to have sent a delegation to Kidal province to offer official condolences on the rebel’s death (Le Republicain [Bamako], August 29). Ag Bahanga was a noted opponent of the political and military domination of Mali by the Bambara, one of the largest Mandé ethnic groups in West Africa (Jeune Afrique, September 8).

The veteran Tuareg rebel had many enemies, including the Algerians, who were incensed by his refusal to adhere to the 2006 Malian peace agreement mediated by Algiers. His rebellion only came to an end when former Tuareg rebels and Bérabiche Arabs joined a Malian government offensive that swept Ag Bahanga and many of his followers from northern Mali in 2009 (see Terrorism Focus, February 25, 2009).

Ag Bahanga returned to Libya, where he became an active recruiter of Tuareg fighters from across the Sahel when the Libyan revolution broke out in February (L’Essor [Bamako], August 29). One returning fighter described seeing Ag Bahanga fighting with loyalist forces at Misrata: “He was with many former rebels from Mali. They were fighting hard for Qaddafi” (The Atlantic, August 31).

If the many reports of Ag Bahanga shipping large quantities of heavy and light weapons and large numbers of 4X4 trucks back to Mali are true, Ag Bahanga was about to become an extremely powerful man in the Sahel. His death will satisfy many, but there are still concerns about the dispersal of his arms, which would certainly be of interest to buyers from al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), which has developed contacts with some young Tuareg by employing them as drivers and guides in unfamiliar territory.

In an interview conducted only days before his death, Ag Bahanga expressed discontent with his one-time patron, offering what might be a bit of revisionist history: “The Tuareg have always wanted Qaddafi to leave Libya, because he always tried to exploit them without any compensation… The disappearance of al-Qaddafi is good news for all the Tuareg in the region…We never had the same goals, but rather the opposite. He has always tried to use the Tuareg for his own ends and to the detriment of the community. His departure from Libya opens the way for a better future and helps to advance our political demands… Al-Qaddafi blocked all solutions to the Tuareg issue… Now he’s gone, we can move forward in our struggle” (El Watan [Algiers], August 29). Ag Bahanga, who at one point had unsuccessfully offered to turn his rebel movement into a transnational security force capable of expelling al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) from the Sahel/Sahara region, also came out against AQIM’s Salafi-Jihadists: “Our imams advocate and educate our youth and families against the religion of intolerance preached by the Salafists, which is in total contradiction with our religious practice. In fact, on an ideological level, the Salafis have no control over the Tuareg. We defend ourselves with our meager resources, and we envision a day soon be able to bring Bamako to account” (El Watan, August 29).

Conclusion

Hundreds of thousands of workers have returned to Niger and Mali, which are unable to provide employment to the returnees. There are also 74,000 workers returning to Chad. Moreover, the loss of remittances from their work in Libya will devastate many already marginal communities reliant on such transfers. Many of the returnees suffered rough treatment at the hands of rebels who consider all black Africans and Tuareg to be mourtazak (mercenaries). Motivation, money, arms and a lack of viable alternatives form a dangerous recipe for years of instability in the Sahel/Sahara region, particularly if it is fuelled by a political cause such as the restoration of the Qaddafi regime or the establishment of an independent Tuareg homeland.

Ana Ag Ateyoub has been mentioned as the most likely rebel leader to succeed Ag Bahanga. Ag Ateyoub has a reputation for being a great strategist but is considered more radical than Ag Bahanga (L’Essor [Bamako], August 29; August 30). Ag Bahanga’s group remains a regional security wild card. If their late leader was actually intending to launch a new rebellion in Mali with high-powered arms obtained in Libya, will the group follow through with these plans?

Former security officials of the Qaddafi regime recently told a pan-Arab daily that Libyan intelligence has conducted extensive surveys of the more inaccessible parts of the country and areas of Niger and Chad while building ties to the local populations in these places (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, September 8). According to a TNC report based on a communication from former Libyan intelligence director Musa Kusa, Qaddafi is now moving between al-Jufrah district in the center of the country, home to a strategically located military base and airstrip at Hun, and the remote Tagharin oasis near the Algerian border, where he is guarded by Tuareg tribesmen (al-Sharq al-Awsat, September 5).

Much of southern Libya and its vital oil and water resources remains outside rebel hands and might remain that way for some time if the Tuareg oppose the new rebel regime in Tripoli. It is possible that Qaddafi may threaten the new government from the vast spaces of southern Libya if he can gain the cooperation of the Tuareg. Despite signs of disenchantment with Qaddafi among the Tuareg tribesmen, there is still the lure presented by the vast sums of cash and gold loyalist forces appear to have moved south on behalf of Qaddafi, who has always understood the need to keep a few billion in cash under the mattress, just in case.

Tuareg rebel leader Agali Alambo believes Qaddafi could lead a prolonged counter-insurgency from the deserts of southern Libya: “I know the Guide well, and what people don’t realize is that he could last in the desert for years. He didn’t need to create a hiding place. He likes the simple life, under a tent, sitting on the sand, drinking camel’s milk. His advantage is that this was already his preferred lifestyle… He is guarded by a special mobile unit made up of members of his family. Those are the only people he trusts” (Fox News, September 13).

Though small in numbers, Tuareg mastery of the terrain of the Sahara/Sahel region, ability to survive in forbidding conditions and skills on the battlefield make them a formidable part of any security equation in the region. Historically, the Tuareg have been divided into a number of confederations and have rarely achieved a consensus on anything, including support for the Libyan regime or the ambitions of those seeking to establish a Tuareg homeland. However, the collapse of the Saharan tourist industry due to the depredations of AQIM and a worsening drought in the Sahel that is threatening the pastoral lifestyle of the Tuareg will only enhance the appeal of a well-rewarded life under arms. The direction of Tuareg military commanders and their followers, whether in support of the Qaddafi regime in Libya or in renewed rebellion in Mali and Niger, will play an essential role in determining the security future of the region, as well as the ability of foreign commercial interests to extract the region’s lucrative oil and uranium resources.

Notes

- For a profile of Ibrahim Ag Bahanga, see Andrew McGregor, “Ibrahim Ag Bahanga: Tuareg Rebel Turns Counterterrorist?” April 2, 2010, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=2773

This article first appeared in the September 16, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor