Andrew McGregor

October 1, 2017

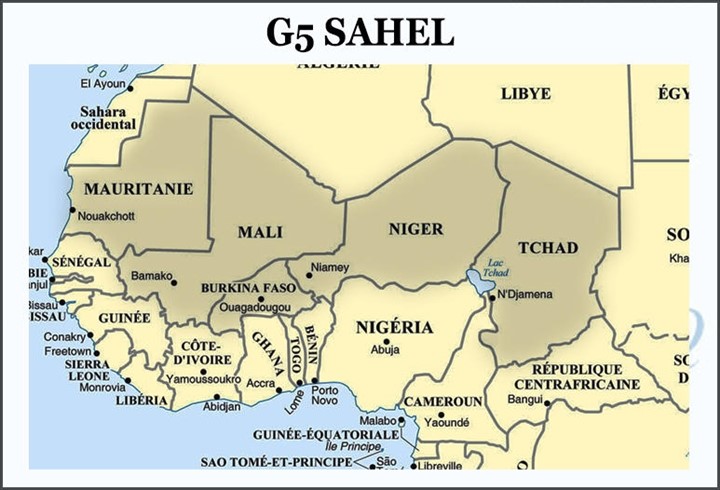

By the late 20th century, the profession of mercenary soldier was generally believed to be a dying trade, left behind by the spread of national armies, the decline of colonialism and the growth of international security cooperation. However, the once discredited profession came roaring back in the early years of the 21st century, often under the slight disguise provided by euphemisms such as “security contractors” or “private military contractors.” In the last two decades, mercenaries have become almost common in conflicts throughout Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe.

FACT Fighters in Libya (Tchad Convergence)

FACT Fighters in Libya (Tchad Convergence)

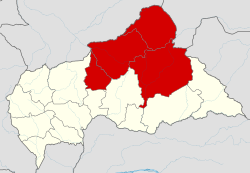

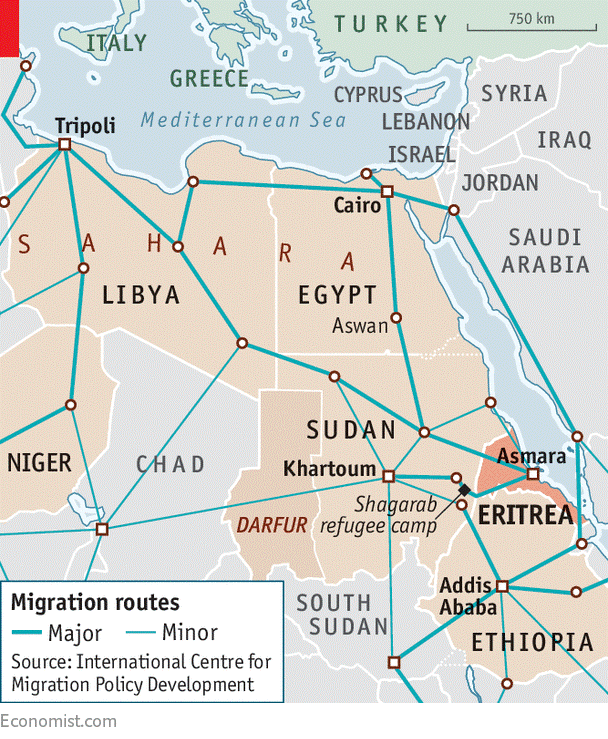

Long-term, small-scale conflicts in resource-rich regions that elude resolution are particularly inviting for modern mercenaries. Oil-rich Libya is a prime example of such opportunities. In April 2017, the foreign minister of Libya’s Tripoli-based Presidency Council estimated the number of Chadian mercenaries operating in Libya to be 18,000, with another 6,000 hailing from Sudan (Libya Herald, August 23). The numbers emphasized the growing problem of mercenary activity in Libya as well as other parts of Africa.

The first of the Chadian armed groups began operations in Libya’s lawless southern Fezzan region in 2014. Though most of these groups presented themselves as rebels opposing the regime of Chadian president Idriss Déby Itno (who took power in a 1990 coup), they shared the common inability to take on Chad’s formidable military. In the meantime, these groups have obtained arms and funding by renting themselves out as mercenaries in Libya’s internal conflict as well as trafficking in people and narcotics through their knowledge of border smuggling routes.

In 2016, Chadian dissident General Mahamat Mahdi Ali gathered many of these groups together under his leadership in the Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT – Front for Alternation and Concord in Chad). Operating out of bases south of the Fezzan capital of Sabha, FACT became allied to the powerful Misratan “Third Force militia” (recently renamed the “13th Brigade”), an Islamist group supporting the UN-recognized Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (PC/GNA) administration in Tripoli. In this capacity, FACT became the enemy of Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA), a coalition of militias supporting the rival House of Representatives (HoR) government in Tripoli. Despite Haftar’s steady stream of anti-mercenary invective directed at the GNA, most of the Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries in Libya operate alongside forces under his command.

Leadership

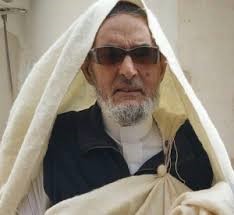

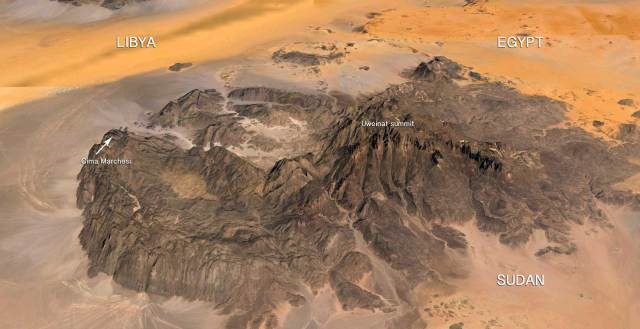

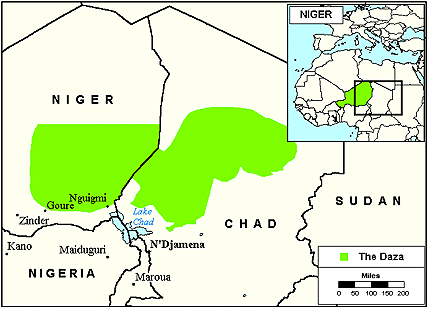

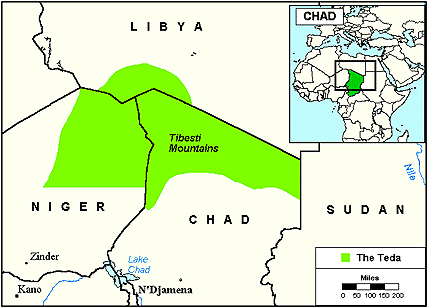

The 48-year-old Mahamat Mahdi is a Daza Tubu of the Kecherda sub-group from the Bahr-el-Ghazal region of northern Chad. The Tubu are a nomadic and semi-nomadic group of roughly 550,000 black Africans speaking a Nilo-Saharan language and sharing cultural similarities with their Tuareg neighbors to the west. Some Tubu have settled into urban communities such as Sabha and Kufra. The Muslim Tubu are divided into two main groups according to dialect — the northern Teda found in southern Libya, northern Chad and Niger, and the much larger Daza group (also known by their Arabic name, Gura’an) found in Chad and Niger. Clan rivalries have traditionally played a negative role in Tubu attempts at political unification.

The Daza Tubu (Joshua Project)

The Daza Tubu (Joshua Project)

Mahamat Mahdi was a leading member of the rebel Mouvement pour la Democratie et la Justice au Tchad (MDJT – Movement for Democracy and Justice in Chad), which operated in Tibesti and other parts of the northern Borku-Ennedi-Tibesti (BET) region of Chad from 1998 to 2003. A ceasefire agreement with N’Djamena provided for positions within the government for leading rebels, and Mahamat Mahdi was accordingly made Inspector of the Ministry of Infrastructure. However, he thought better of remaining in N’Djamena when a wave of assassinations began to strike Déby’s political opponents and joined General Mahamat Nouri’s Sudanese-backed Union des Forces pour la Démocratie et le Developpement (UFDD – Union of Forces for Democracy and Development) (Libération, May 29; PANA, December 16, 2003; Le Visionnaire, June 28, 2016).

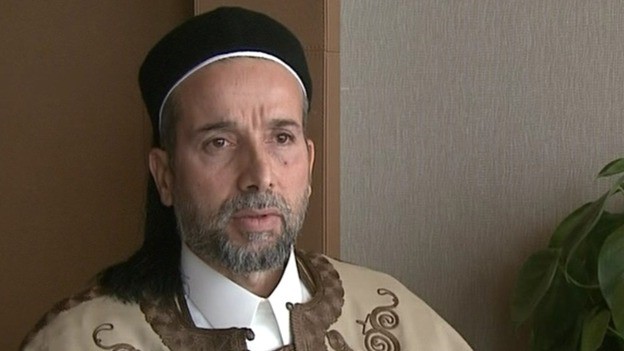

The Teda Tubu (Joshua Project)

The Teda Tubu (Joshua Project)

Nouri, a Daza Tubu of the Anakaza sub-group was the defense minister in the government of President Hissène Habré, a fellow Anakaza who ruled Chad from 1982 to 1990 before being deposed by General Déby (from the Zaghawa, a group closely related to the Tubu). [1] In 2009, Mahamat Mahdi became secretary-general of the group, mainly composed of Daza Tubu from the Tibesti Mountains, with the Anakaza sub-group as Nouri’s core supporters. [2]

In February 2008, the UFDD reached the Chadian capital of N’Djamena from its bases across the border in Darfur, but was repelled in violent street fighting by forces personally led by President Déby, a reminder that political life had not dulled the ex-general’s tactical edge (TchadActuel, February 17, 2008; Jeune Afrique, February 11, 2008; Le Nouvel Observateur, March 6, 2008).

A 2010 rapprochement between Chad and Sudan put an end to their mutual support for cross-border rebel groups such as the UFDD. Mahamat Mahdi eventually joined Mahamat Nouri in French exile (Chad is a former French colony), but Nouri ordered him to Libya in 2015 in an attempt to revive the UFDD.

Origins of FACT

Most of the prospective fighters for the revived group came from the Kreda and Kecherda sub-groups of the Daza Tubu. Mahamat Mahdi used his influence, particularly among his fellow Kecherda, to bring these fighters under his personal control rather than that of Mahamat Nouri, who could exert little control over the process from his Paris exile. [3] Following a clash between Mahamat Mahdi’s supporters and Nouri’s Anakaza supporters that left 20 of the latter dead, Mahamat Mahdi declared the formation of a new rebel movement, FACT, in March 2016 (VOA/AFP, April 8, 2016). The movement established an operational base inside Chad at Tanoua, a region close to the Libyan border.

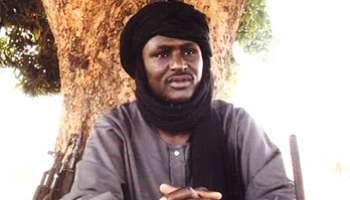

FACT commander Mahamat Mahdi Ali (Taha Jawashi/Libération).

FACT commander Mahamat Mahdi Ali (Taha Jawashi/Libération).

Now with a movement of his own behind him, Mahamat Mahdi pointed to the Chadian elections that followed a few weeks later as proof that political change in Chad was impossible through the ballot box:

At the beginning, we hoped that there would be a political change at the end of the presidential election. But it was well known that Déby would not give up power. We saw the result: the real winner was robbed of his victory, the ballot boxes were stuffed, the opposition activists were intimidated… The regime has also tried to divide our movement. Only force will make Déby leave, it is our conviction. Slowly but surely, we are preparing to reach our goal… to put an end to this anarchic regime dominated by a small group of men. We have no personal ambitions. We will not fight to retain power. It is no longer possible nowadays to take power with some 4x4s [as Déby did in 1990] and to keep it (Jeune Afrique, December 21, 2016). [4]

Mercenary Activities

FACT quickly split in June 2016, when its Kreda clan fighters followed former UFDD spokesman Mahamat Hassani Bulmay into a new group, the Conseil de Commandement Militaire pour le Salut de la République (CCMSR – Military Command Council for the Salvation of the Republic), which later allied itself with the Islamist Libyan militant group Benghazi Defense Brigades (BDB).

Unlike the Chadian armed groups that sold their services to Haftar’s LNA, FACT’s alliance with the Misratan Third Force and the BDB brought it unwanted attention from the LNA air force. The group’s base at Doualki, near Sabha, was attacked by LNA aircraft on April 14, 2016. [5] FACT’s rear base at Jabal Saoudah near the Chadian border was attacked by LNA aircraft in mid-December 2016, a strike the movement blamed on collusion between the HoR government in Tobruk and the administration in N’Djamena (Tchadconvergance/AFP, December 13, 2016).

LNA warplanes also bombed FACT positions in Jufra. Mahamat Mahdi claimed the attack took him by surprise: “We thought it was an error at first, until Haftar’s entourage asserted that the purpose was to annihilate any rebellion that might destabilize a neighboring state” (Jeune Afrique, December 21, 2016).

According to the UN, FACT participated in the BDB’s March 2017 attack on the LNA-held Ras Lanuf and Sidra oil facilities on the Mediterranean coast, losing a senior commander in the process. [6] FACT was also reported to be involved in clashes with the LNA around the important Tamenhint airbase northeast of the Fezzan capital of Sahba in mid-April, though Mahamat Mahdi denied involvement (RFI, April 16). In retaliation, the LNA’s 116th Battalion shelled the Chadian camps south of Sabha in June after driving the Misratans from Tamenhint (Facebook in Arabic, June 15, via BBC Monitoring).

Despite much evidence of involvement, General Mahamat Mahdi maintains that FACT has a neutral stance in the Libyan conflict: “It is a position of principle and common sense: we are Chadian rebels, we have no reason to interfere with the Libyan problems” (Jeune Afrique, December 21, 2016). The General claims Haftar is colluding with Déby against him.

Chad closed its border with Libya in early January, fearing infiltration of its borders by Tubu rebels and Libyan Islamic State (IS) fighters fleeing northern Libya after the loss of their stronghold at Sirte (Reuters, January 5). France also imposed financial sanctions on Mahamat Mahdi Ali and his rival Mahamat Nouri on January 19. Nonetheless, Mahamat Mahdi claims that FACT has actually helped prevent the southwards penetration of IS fighters: “We oppose groups like the Islamic State that deny human rights. Our presence is a bulwark to their advance towards Libyan south” (Jeune Afrique, December 21, 2016). Two months later, he emphasized: “Today the only concern is how to contain the Islamic State” (RFI, February 27, 2016).

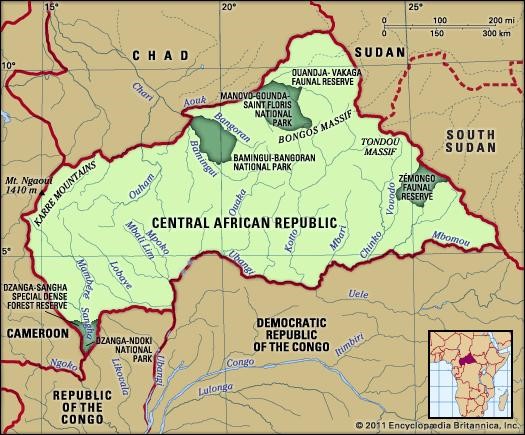

The Role of Qatar

Chad announced on August 23 that it was suspending diplomatic relations with Qatar over “the continued involvement of the state of Qatar in attempts to destabilize Chad from Libya” (La Tribune Afrique, August 23; Reuters, August 23). N’Djamena insists it has “irrefutable proof” that Qatar supports and finances Chadian opposition groups based in Libya, despite denials from Doha (RFI, August 26). Chadian Foreign Minister Hissein Brahim Taha stressed that his government’s dispute with Qatar is strictly a bilateral issue and “not the continuation of the diplomatic crisis” in the Gulf region (La Tribune Afrique, August 24).

N’Djamena claims the Qatari financing is funnelled through long-time Chadian rebel leader Timan Erdimi, who has made Doha his home since 2009. (RFI, August 26). Chad has sought Erdimi’s extradition for several months (La Tribune Afrique, August 24). Erdimi is Déby’s nephew and leader of the Union des forces de la résistance (UFR), a Libyan-based Chadian rebel movement that has provided mercenary support for Haftar’s LNA in the battle for Benghazi and was attacked by the Subul al-Salam Brigade for its involvement in criminal activities around Kufra. Subul al-Salam is a Salafist unit affiliated with Haftar’s LNA and composed largely of Zuwaya Arabs, the dominant Arab group in the Kufra region.

A Libyan-based Chadian rebel group was reported to have crossed the border on the weekend of August 19-20, killing a number of Chadian government troops in a surprise attack. UFR spokesman Yusuf Hamid insists his group was not responsible for the attack: “I categorically deny the accusations of the Chadian government. We did not get anything from Qatar, not a single penny, not a small piece of equipment. Nothing.” (RFI, August 24). If true, this leaves the possibility that the strike was undertaken by Mahamat Mahdi’s larger FACT movement (though there remains a chance it could have been the work of one of the lesser Chadian armed groups active in southern Libya).

Two members of the Kufra-based Subul al-Salam Battalion in southeastern Libya were killed during a clash with Chadian gunmen on August 26. The clash occurred in the Hanagar region some 300 kilometers southwest of Kufra, where the same two groups battled last February. Subul al-Salam claimed to have killed seven Chadians, whose identity cards suggested they were mercenaries working for the LNA-affiliated Ali al-Thumin Brigade (Libya Herald, August 26; Libya Observer, August 26; Libya Observer, February 2; Libyan Express, August 26). The Battalion has also engaged several times in the last few years with Darfur rebels now operating in the region as mercenaries or highwaymen.

Conclusion

Mahamat Mahdi Ali is a strong irritation for the Déby regime in Chad but a constant source of destabilization in Libya. Despite Mahamat Mahdi’s frequent assertions that times have changed, it seems difficult to identify any other plan for him to achieve regime change in N’Djamena other than “to take power with some 4x4s.” Beyond his core group of up to 1500 fighters (some of whom may be in it strictly for the money), there is little evidence of popular support for Mahamat Mahdi’s movement within Chad, where both government and opposition continue to be dominated by the Tubu and related groups, a tiny minority of Chad’s total population. In addition, President Déby’s authoritarianism is overlooked by France and the United States, which value him as a partner in the War on Terrorism. Mahamat Mahdi Ali is thus an important example of a new type of African mercenary ready and willing to exploit regional conflicts for profit while using the cover of legitimate political resistance.

Notes

[1] After a long legal odyssey, Habré was sentenced to life in prison on May 30, 2016 by a Special African Tribunal in Senegal for mass-torture, rape and the murder of 40,000 Chadians during his time as president.

[2] Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to resolution 1973 (2011), United Nations Security Council, S/2017/466, June 1, 2017, http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/N1711623.pdf

[3] Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, “Tubu Trouble: State and Statelessness in the Chad-Sudan-Libya Triangle,” Small Arms Survey, Geneva, 2017, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/working-papers/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf

[4] The tactics of using 4×4 trucks equipped with anti-tank missiles and heavy machine guns were perfected by General Hassan Djamous (Bidayat) during the 1987 “Toyota War” between Chad and Libya and have been used in a variety of military campaigns in the Sahara/Sahel region since.

[5] Final Report, op cit.

[6] Ibid.