Andrew McGregor

February 12, 2009

In March 2005, an earlier 2004 UN arms embargo on non-government forces in the Darfur conflict was expanded by the UN Security Council to include the Sudan government. Russia approved the passage of UN Resolution 1591, which bans the transfer of weapons to Darfur without the Security Council’s permission. What is poorly understood is that Khartoum is still allowed to purchase all the arms it wants if the arms are designated for use outside of Darfur. Though deployment of new military equipment to Darfur must be approved by a UN committee on Sudan sanctions, Khartoum’s disregard for this provision has left a giant hole in the arms embargo.

Sudanese Troops on a Russian-made T-54 Tank

Sudanese Troops on a Russian-made T-54 Tank

Commenting on reports that Russia had transferred 33 military aircraft to Sudan since 2004, David Miliband the UK Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs noted the limitations of the UN embargo; “The UK continues to request that the UN extend its arms embargo on Darfur to all of Sudan, but not all Security Council members agree” (UK House of Commons, Hansard, November 6, 2008).

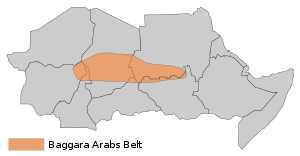

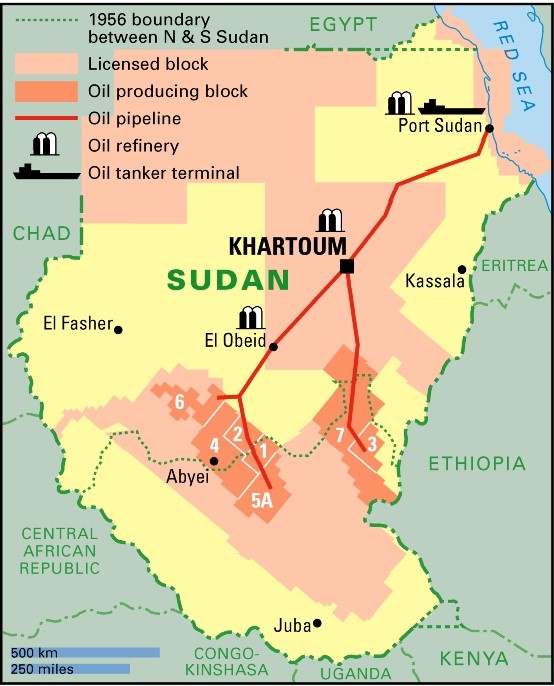

One of the issues Russia’s new envoy must be dealing with is Khartoum’s concerns over Russia’s role in providing arms to South Sudan’s Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) – arms that will almost certainly be used against government forces if fighting resumes between the South and the military-Islamist government in Khartoum. The Juba-based Government of South Sudan is building one of the largest armies in Africa with its share of Sudan’s oil revenues and may soon be in the market for its own jet fighters. The 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement between north and south Sudan forbids either side from making major arms purchases without permission from a Joint Defense Board, though this provision is widely ignored by both sides (Anyuak Media, January 10).

The recently released Ukrainian cargo-ship, MV Faina, seized by Somali pirates in September, held 33 Russian-designed T-72 battle tanks and a substantial cargo of grenade launchers, anti-aircraft guns, small arms and ammunition believed to be on their way to landlocked South Sudan via Mombasa. The ship was released on February 5 after the payment of a reported ransom of $3.2 million, a fraction of the $35 million originally demanded (RIA Novosti, February 5). The American destroyer Mason and ocean tug Catawba provided the ship with fuel, water and humanitarian assistance as it proceeded to Mombasa, a transit point for arms shipments to South Sudan (Navy News, February 6). Unlike earlier arms shipments to South Sudan through Kenya that attracted little attention, the destination of the tanks and other arms will be closely watched by a host of interested parties. Both Ukrainian intelligence and Kenya’s Defense Ministry insist the arms are destined for the Kenyan army, even though it does not use any Russian-designed equipment and has no training on Russian-designed equipment (Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 29, 2008). The ship’s manifest, released by the pirates, indicated the end recipient of the cargo was “GOSS,” the usual acronym for the Government of South Sudan.

Russian arms appeal to many countries with limited budgets, harsh conditions or a poorly-educated military. According to Russian defense analyst Pavel Felgenhauer, the continued production of outdated Soviet military equipment to developing countries has become a lucrative business:

The so-called production of arms using Soviet designs and equipment, a Soviet-trained workforce and Soviet-made weapons repainted to look like new is typical in the defense industry today. This keeps production costs low and profits high, while the veil of secrecy surrounding the arms trade allows firms to avoid taxes almost entirely… There is hardly a local war or conflict in the world where Russian arms are not extensively employed because they are reliable, relatively cheap and often specifically designed in the Soviet era for use by poorly trained and educated conscript soldiers (Moscow Times, July 27, 2004).

Konstantin Makienko of the Center for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies has offered an explanation for why Sudan and other African nations prefer to stick with Russian arms:

The presence of conflicts naturally leads to a demand for armaments, with the priority on the fastest possible delivery of low-cost weapons, especially those that are simple to use and maintain and which have been either used by the army in question or which could be supplied along with personnel from abroad to maintain the equipment. These factors encourage repeat purchases from the same suppliers (Moscow Defense Brief 4 (14), 2008).

Though China is frequently criticized for its arms shipments to Sudan, Russia has more quietly become Khartoum’s major arms supplier, an activity in which it has been joined by former Soviet states such as Belarus and Ukraine. A SIPRI report based on its Arms Transfers Database stated that Russia had accounted for 87 percent of Sudan’s major conventional weapons purchases in the period 2003-2007, while China was responsible for only eight percent (www.sipri.org/content/<wbr></wbr>armstrad/2008/04/01).

In a sense, it is a return for the Russians -the Soviet Union dominated the Sudanese market for military equipment after the left-leaning Revolutionary Command Council led by General Ja’afar Muhammad Nimeiri took power in May 1969 and began a massive expansion of the Sudanese military. The Soviets supplied armor, artillery, MiG-21 fighters, Antonov cargo planes and various military helicopters as well as Soviet technicians and trainers. By 1971, however, Nimeiri was purging communists from the government and banning communist-affiliated trade unions and professional associations. The Sudanese Communist Party responded with a violent three-day coup attempt in July, 1971 that ultimately failed when troops loyal to Nimeiri rallied for a counter-attack. Suspicions of Soviet involvement brought a swift deterioration in Soviet-Sudanese relations. When the Soviets backed the 1977 Marxist military coup in Sudan’s rival, Ethiopia, the remaining Soviet military advisors in Sudan were expelled and Khartoum turned to a new supplier, the United States.

In 2006, the Russian press reported that Sudan was seeking not only new Russian arms, but also a $1 billion long-term loan to help pay for them. The request did not receive a warm response in Moscow, where memories are still fresh of the write-offs of billions in debt incurred by African nations purchasing arms on credit in the 1970s and 1980s (Kommersant, October 20, 2006).

The Sudanese army operates over 200 Russian-model T54 and T55 battle tanks, obtained from Russia, Belarus and Poland (the latter through a secondary sale by Yemen, which acts as a kind of arms bazaar for the region). The tanks are obsolete in the European context, but are still useful for providing fire support to infantry operations in Sudan. Khartoum, however, has switched to Chinese-made battle tanks and apparently intends to look to China for most future purchases of armor. Sudan has also purchased as many as 60 Soviet-designed BTR-80A armored personnel carriers from Russia in recent years.

In July 2008, International Criminal Courts (ICC) prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo charged Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir with various counts of genocide, crimes against humanity and murder. The ICC is still reviewing the charges, which will likely go forward unless there is intervention at the UN Security Council level, most likely from China or Russia.

With ongoing sanctions, international disapproval and possible war crimes charges pending against the Sudanese president, Moscow is well aware the Khartoum regime is looking for allies, especially ones with a presence on the UN Security Council. Russia has not yet announced its position on trying al-Bashir in the ICC, but has hinted it may be willing to support a deferral of the charges (Sudan Tribune, January 31). Supported by new-found wealth from its own immense oil industry, Russia’s new engagement with Sudan is an expression of Russia’s new confidence and apparent eagerness to pursue an aggressive and exclusive foreign policy. Sudan, of course, is not the only African nation to purchase large quantities of Russian arms, but it is a vast, strategically important, resource-rich nation with minimal American presence or influence. As such, it represents an important gateway for Russia to rebuild its once-formidable stature and presence in Africa.

This article was first published in the February 12, 2009 issue of the Eurasia Daily Monitor