Andrew McGregor

March 8, 2013

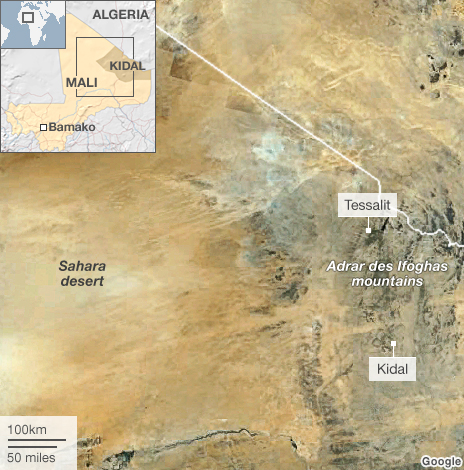

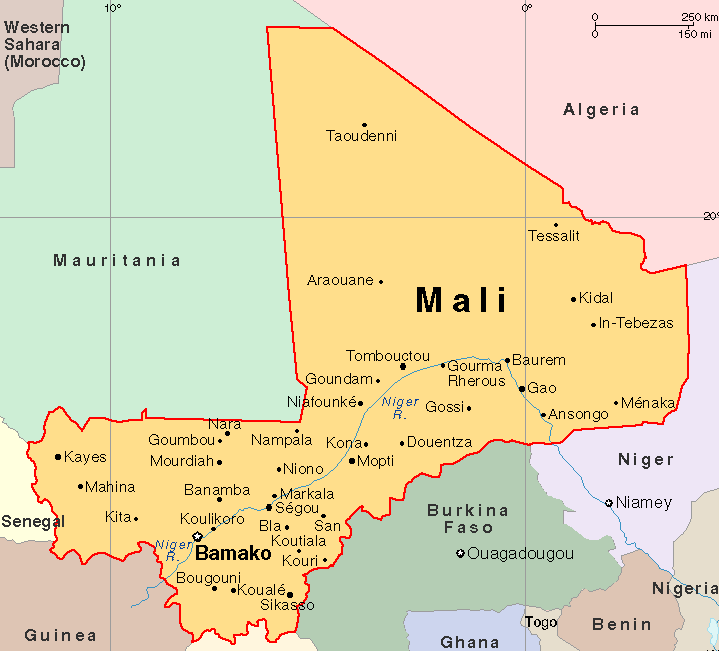

The military situation in the Kidal region of northern Mali is growing more complex by the day. France is conducting counterterrorist operations in the region with its Chadian and Nigérien allies while soldiers of the Malian Army remain excluded from the zone at the request of two Tuareg rebel groups Bamako would like to eliminate – the separatist Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) and the Islamist Mouvement Islamique de l’Azawad (MIA), recently formed by defectors from Iyad ag Ghali’s Ansar al-Din. It is France’s military cooperation with the MNLA (and to a lesser extent with the MIA) in securing Kidal that is now threatening to ignite a tribal war in northern Mali.

French Colonial-era Fort in Kidal. Built 1917. (Vitka)

French Colonial-era Fort in Kidal. Built 1917. (Vitka)

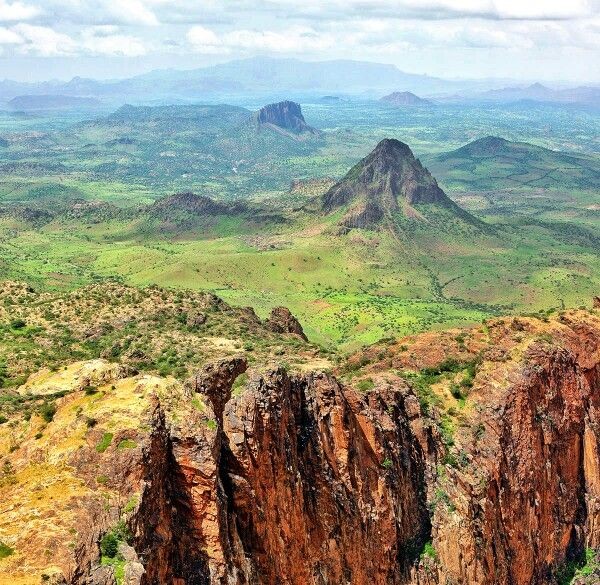

For France, cooperation with the Tuareg MNLA is a military necessity. The movement is largely drawn from the local Ifoghas Tuareg and guides with intimate knowledge of the terrain are essential in the campaign to exterminate the well-armed Islamists hidden in the caves, rocks and vegetation of the mountainous Tigharghar region. Likewise, the MIA is seen as useful in tracking down fugitive Tuareg Islamists from Ansar al-Din, including the movement’s leader, Iyad ag Ghali. The Islamists have already proven their ability to launch devastating ambushes on the counterterrorist forces. For northern Mali’s Arab minority, however, the military alliance between intervention forces and the Tuareg rebels has revived the ancient rivalry between the Arab tribes and the Berber Tuareg. With this rivalry now erupting into armed clashes and the Malian Army (largely composed of Black African tribes from the south) now accused of excesses against the lighter-skinned Tuareg and Arabs in Timbuktu and Gao, the French military now faces the danger of being drawn into a new tribal conflict that will inevitably set back efforts to rid northern Mali of jihadis and narco-traffickers.

Arabs form approximately 10% of northern Mali’s population of 1.2 million, while the Tuareg account for roughly 50%. The main Arab groups are the Bérabiche (who worked closely with the French in the original conquest of northern Mali 119 years ago), the “noble” Kunta and the Telemsi. The Arab tribes are not any better known for inter-tribal cooperation than the fractious Tuareg tribes.

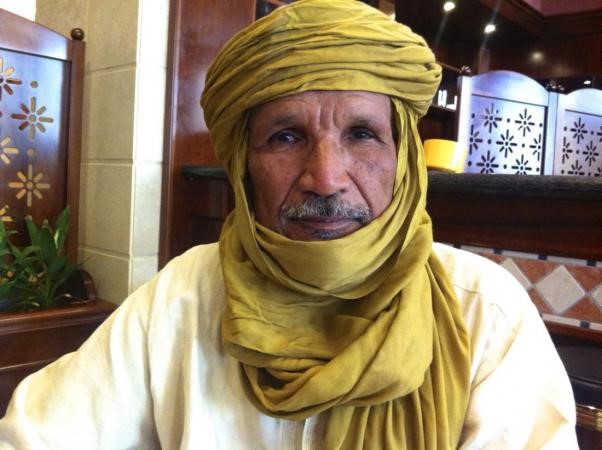

The situation in Kidal was described by Muhamad Mahmud al-Oumrany, a former ambassador and the current president of the Arab Community of Mali:

“The whole Arab community, which was residing in Al-Khalil, was forced to evacuate the town. It is the first time that ethnic cleansing by a community of another. The cause is that the Kidal area is regarded today as a safe haven for the MNLA. There is no Malian army to restore stability, to restore the law. It is only the MNLA that is in the region. It loots and if any protest is made, it runs to the French army to say: “These are Islamists. They are terrorists.” It is an unacceptable situation and it is going to lead definitely to a clash between the Arab and Tuareg communities” (RFI, March 3).

Al-Oumrany is more favorable to the MIA, under the leadership of Algabass ag Intallah, saying that the noble Intallah family is the key to restoring security to the Kidal region (RFI, March 3).

Unfortunately for the Arabs, their community is hardly free of associations with AQIM and its ally, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA). Many of the Bérabiche Arabs of northern Mali have cooperated with the AQIM presence for several years out of a combination of economic necessity and ethnic solidarity. For some Arabs, it is the ideological appeal of al-Qaeda that has drawn them into their ranks. Omar Ould Hamaha, a Timbuktu Bérabiche Arab, is the leader of MUJWA and recently formed a local Bérabiche version of Ansar al-Shari’a on December 9, 2012 to protect Arab interests and promote jihad in the Arab community.

The Arab community in Timbuktu has warned of retaliatory ethnic violence in the wake of abuses committed by the Malian Army and even other civilians who do not differentiate between Malian Arabs and al-Qaeda jihadists (RFI, February 23). The community has sent representatives to Paris to plead their case and is urging that Colonel Ould Meydou, a Telemsi Arab, be released from Bamako to lead his largely Bérabiche Arab militia into Timbuktu to restore order (RFI, February 23). The colonel is unpopular with the Malian Army putschists, who have refused to allow him to use his considerable desert-fighting skills against the Islamists. The MNLA strongly dislike Meydou – many of them have clashed with him before in earlier Tuareg rebel formations.

Arab refugees in Mauritania have also mounted protests against what they describe as “ethnic cleansing” by the Malian Army, citing a number of massacres, missing people taken by soldiers and other disorders that are difficult to confirm in the tight information regime currently imposed on northern Mali (al-Akhbar [Nouakchott], February 20; February 22). Despite this, a number of Malian officers and men have been recalled to Bamako for investigation into human rights abuses committed in the wake of the French advance.

In response to these abuses, the Arab community of northern Mali has created a secular self-defense militia with an estimated 500 members. The Mouvement arabe de l’Azawad (MAA) was created in February, 2012 as the Front de Libération nationale de l’Azawad (FNLA) and formed from members of earlier Arab militias and Arab soldiers of the Malian Army who defected after the fall of Timbuktu. Since the rebellion began last year, the movement has drawn increasing numbers of young Arab men looking for some form of protection for their community (Sahara Press, January 12, 2012). The MAA has two strongholds in northern Mali, the first at Telemsi near the Mauritanian border and the second at Tinafareg close to the border with Algeria.

MAA secretary general Ahmad Ould Sidi Muhammad has warned of an ethnic conflict between Arabs and Tuareg and has called for Mauritania and Algeria to be aware of “the grave danger of this unholy alliance between France and the MNLA and the dangerous implications for the region’s people” (Sahara Media, March 4).

A large number of Arabs from Timbuktu took refuge from the Malian Army in the border town of al-Khalil (or In Khalil), a small but strategically important town that controls both smuggling and legal trade across the Algerian border. As such, it formed the last base for AQIM Amir Mokhtar Belmokhtar before it was occupied by the French. After the arrival of the French, the Arab refugees began to complain of rough treatment by the MNLA, including car-theft, looting and ultimately rape (Algerie1.com, February 23). The MNLA occupation, according to the movement, was designed to cut off the Islamists in the Adrar des Ifoghas from food, fuel and other supplies brought in by smugglers.

On February 23, a column of up to 30 vehicles attacked the MNLA based at al-Khalil. The MNLA claimed that they were under attack from elements of MUJWA under Ould Hamaha supported by Ansar al-Shari’a and MAA fighters under the command of MAA chief-of-staff Colonel Hussein Ould Ghulam, a defector from the national army (Combat [Bamako], February 23). The MNLA succeeded in selling this version of events to the French, who launched airstrikes on the MAA, destroying several vehicles. The MAA withdrew from the attack and returned to their base in the In Farah region close to the border with Algeria, furious at the French intervention on behalf of the MNLA (RFI, February 25). MUJWA claimed responsibility for two car bombs that went off in near MNLA checkpoints that killed two Tuareg fighters on February 22, but made no comment on their alleged role in a battle with the MNLA and French units (RFI, February 23).

An MAA leader, Boubacar Ould Talib, suggested that it was “illogical” for the MAA to cooperate with the Islamists: “We came to al-Khalil to ensure the security and safety of the Arab interests and we will never coordinate with the terrorists in that.” Ould Talib also stated that the MAA was ready to coordinate in counterterrorist efforts with the French at any time (al-Sharq al-Awsat, February 27). The day after the attack on al-Khalil there were fresh clashes between the MAA and MNLA near Tessalit, where the Arab movement claimed the MNLA Tuaregs had committed numerous abuses against the Arab residents (RFI, February 24).

French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian has said: “In Kidal, we are living a particular situation and we do our best to be on good terms with the Tuaregs” (RFI, February 23). However, the defense minister has here ignored the fact that French forces are also fighting alongside the Imghad Tuareg militia led by Colonel al-Hajj ag Gamou, bitter enemies of the Ifoghas leadership of the MNLA and the MIA. At some point, all the contradictions of the French campaign in northern Mali will catch up with it, unless the French succeed in pulling out first. In either case, the hastily-planned intervention has consistently ignored the political and sociological aspects of the campaign, likely at a great future cost to the inhabitants of northern Mali.

This article first appeared in the March 8, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor