Andrew McGregor

November 28, 2013

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM) is the Egyptian branch of a Gazan Islamist organization that first appeared in the Sinai in the days after the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Since then, ABM has become one of the most active and aggressive of the many militant groups now found in the Sinai. Its latest high-profile operation was the November 17 assassination in Nasr City of Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Mabrouk Abu Khattab of Egypt’s National Security Agency (NSA), one of the leading investigators involved in the prosecution of ex-president Muhammad Mursi and other leading members of the Muslim Brotherhood. In the past, ABM has mounted several attacks on the pipelines that carry Egyptian natural gas to Israeli and Jordanian markets, claimed responsibility for an attack on Israeli troops in September, 2012 and attempted to assassinate Egyptian Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim on September 5 (Daily News Egypt, July 26, 2012).

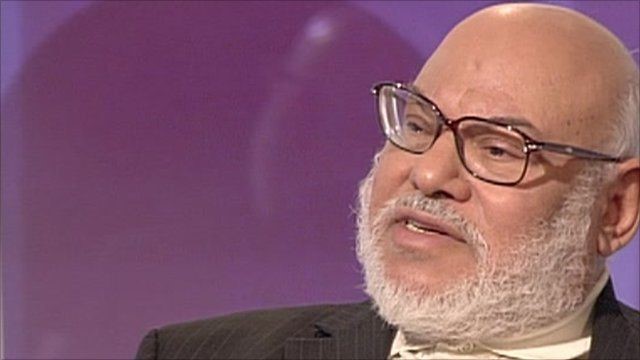

Lieutenant Colonel Muhammad Mabrouk

In its claim of responsibility for the murder of Colonel Mabrouk, ABM maintained that it had targeted the senior investigator over the commitment to trial in Alexandria of 15 women and seven girls for participation in a violent pro-Mursi demonstration in Alexandria in October: “[Mabrouk] was one of the major tyrants of the state security apparatus and the assassination was a response to the arrest of free women by this malicious apparatus.” The statement ended by promising further attacks if the women were not freed. [1]Given Mabrouk’s peripheral connection with the Alexandria case, prosecutors suspected the ABM statement was intended to mislead their investigations and asked the Interior Ministry to investigate the declaration (al-Masry al-Youm, November 21).

Suspicion of complicity in the assassination has fallen on the Muslim Brotherhood, which condemned the attack on November 19 and assailed efforts by the media to associate them with the assassination (Daily News Egypt, November 20). The timing of Mabrouk’s murder is noteworthy, as it came shortly before his testimony in the Mursi trial and a week after submitting a CD supporting the charges of spying leveled against the ex-president. Judicial sources have indicated that the CD includes a recording of a phone call between Mursi and al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri as well as another phone conversation in which Mursi admits providing Hamas with information on the security situation in the Sinai (al-Masry al-Youm, November 21). Colonel Mabrouk played a central role in taking down the Muslim Brotherhood leadership, arresting leading members such as Khayrat al-Shater, Essam al-Erian and Muhammad al-Beltagy. The spying charges actually predate Mursi’s removal as president; the case accusing Mursi and 13 other members of the Muslim Brotherhood of spying and illegal contacts with foreign entities was forwarded to prosecutors by the Ismailia Appeals Court on June 23 (al-Ahram Weekly, November 22). Mabrouk was also expected to be the chief witness in a separate case regarding Mursi’s Hamas-assisted escape from Wadi al-Natrun prison five days after the January 25 Revolution.

According to the ABM statement, the killing was carried out by the Mu’tasim Bi-‘llah Battalion. This ABM faction is named for al-Mu’tasim Bi-‘llah, the eighth Abbasid caliph (795 – 842), known for his fighting skills and his campaigns against the Christian Byzantine Empire. As justification for the murder, the ABM statement cited an episode from the life of the Prophet Muhammad, in which the Prophet attacked and expelled the Jewish Banu Qaynuqa tribe after an incident in the market in which a Jewish goldsmith is said to have pinned the clothes of a Muslim woman so as to cause her to be stripped naked when she walked away. The Jewish merchant was immediately killed by a passing Muslim, who was in turn killed by a Jewish mob, leading to the Prophet’s eventual attack. [2] ABM asks, on the basis of this precedent, what alternative do Muslims have when faced with the detention and assault of hundreds of Muslim women?

Mabrouk’s funeral was attended by Prime Minister Hazem al-Beblawi, Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim and several other ministers and high officials. A three-day mourning period was announced by interim president Adli Mansour on November 20 (Egypt State Information Service, November 21). The Interior Ministry claims 152 “martyrs” have been lost to militant activities since Mursi’s June 30 overthrow.

Colonel Mabrouk was only the latest in a series of Interior Ministry personnel (many of whom conceal their identities and rarely work in the field) to be targeted by assassins. Revelations of the existence of “assassination lists” with the home addresses of intelligence officers involved in the crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood are reported to have prompted a deadline of January for Interior Minister Muhammad Ibrahim to discover the leak in his Ministry (Ahram Online [Cairo], November 22; al-Ahram Weekly [Cairo], November 22).

On November 21, police in the Delta town of Qaha raided an apartment in search of two suspected terrorists wanted in connection to the murder of Colonel Mabrouk, the attempted assassination of Interior Minister Ibrahim and an attack on a Coptic church. The two were arrested only after a gunfight that killed police Captain Ahmad Samir al-Kabir (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], November 21; November 22).

On the following day, the Egyptian Ministry of the Interior announced the arrest of the prime suspect in the Mabrouk assassination, Shady al-Manei, described as a leading member of Bayt al-Maqdis. Al-Manei was alleged to be a subordinate of Muslim Brotherhood deputy guide Muhammad Khayrat al-Shater (presently detained) and was previously imprisoned in connection with the 2005 Taba bombings before being released by ex-president Muhammad Mursi (Egypt State Information Service, November 23). Nabil Na’im, a fierce opponent of the Muslim Brotherhood and leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad from 1988 to 1992, has accused al-Shater, a prominent businessman, of funding ABM’s strikes on Egyptian security forces (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], September 9; for Khayrat al-Shater, see Militant Leadership Monitor, September 2013).

The Egyptian Army has not failed to respond to the ABM’s attacks on security personnel. On November 26, four black Army Humvees pursued and killed Shaykh Abu Munir (a.k.a. Muhammad Hussein Muhareb) and his son at al-Mehediya in the northeast Sinai. Abu Munir was an associate of ABM and a prime suspect in the brutal roadside murder of 25 police recruits dragged from their bus in August (Aswat Masriya [Cairo], November 26; Telegraph, November 26).

On November 20, ABM released the identity of the suicide bomber who attacked the South Sinai security directorate on October 7, killing five soldiers and wounding 50 others. The “martyr,” Muhammad Hamdan al-Sawarka (a.k.a. Abu Hajer), was a member of the Sawarka tribe, one of the Sinai’s largest. The ABM statement also criticized prominent Egyptian Salafist leaders for failing to resist the overthrow of Muhammad Mursi (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], November 20).

In his assessment of the Sinai campaign of the Egyptian security forces, Dr. Najih Ibrahim, a founding member of the extremist al-Gama’a al-Islamiya who has since renounced political violence, commented:

This campaign has largely succeeded. Without it, Egypt would have witnessed a long series of car bombings. We must admit that this military campaign prevented the arrival of this danger to the Nile Delta and to Cairo in a major way. Extremists in Sinai can equip a thousand booby-trapped cars and dispatch them to other areas in Egypt. The military campaign destroyed many mine and weapons stockpiles, and many of those who committed terrorist attacks were arrested. Many smuggling tunnels were closed and the sources of funding for these groups in the Sinai were controlled (As-Safir [Cairo], November 25).

Notes

1. Jama’at Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, “Declaring our responsibility for assassinating the criminal Muhammad Mabrouk,” November 19, 2013, http://www.ansar1.info/showthread.php?t=47326

2. The incident is related in Ibn Hisham’s (died c. 830) Al-Sirah al-Nabawiyah , an edited version of Ibn Ishaq’s biography of the Prophet Muhammad (now lost).

This article first appeared in the November 28 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.