Andrew McGregor

April 22, 2010

With al-Qaeda activities in the Sahel/Sahara region of Africa creating havoc with commerce, trade, resource extraction, tourism and general security, the nations of the region appear ready to mount a coordinated military approach to the elimination of Salafist militants. Algeria, with the largest and best-armed of the militaries in the region, launched a sweeping counter-terrorism offensive last week, entitled Operation Ennasr (“Victory”).

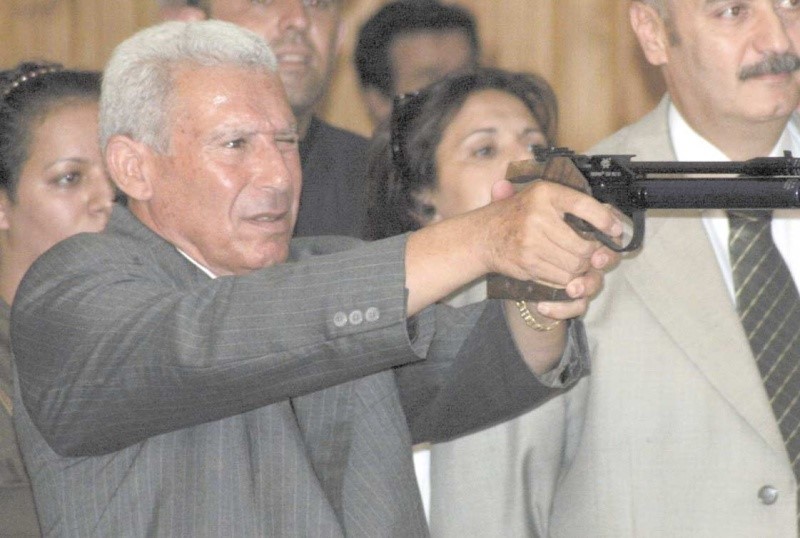

Major General Ahmad Gaid Salah

Major General Ahmad Gaid Salah

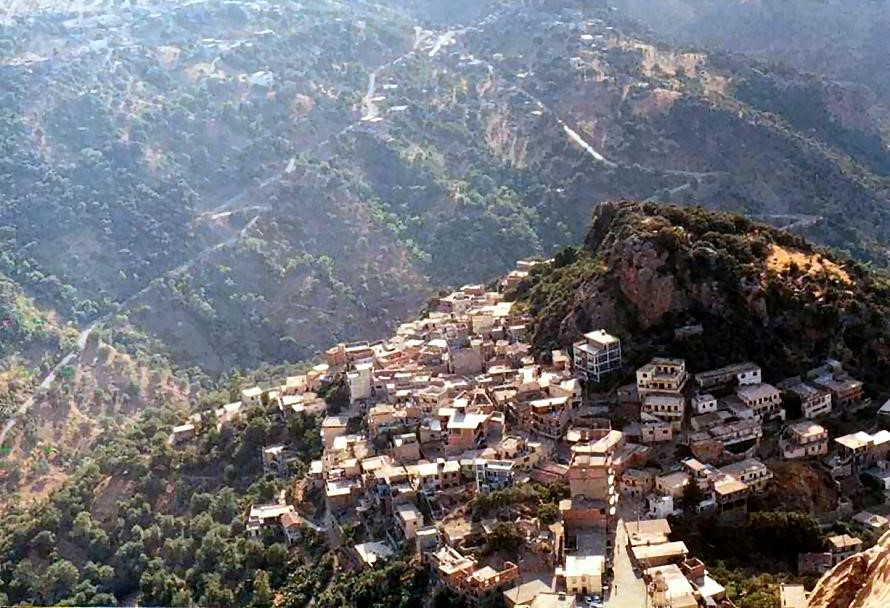

Algeria’s Armée Nationale Populaire (ANP) is under orders from the army’s chief-of-staff, Major-General Ahmad Gaid Salah, to “clean out the terrorist maquis” (Liberté [Algiers], April 13). The operation is targeting bases of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in the western, central and eastern parts of Algeria. Unlike operations in the desert regions of south Algeria, Operation Ennasr is focusing on the mountainous and heavily wooded regions where AQIM has its hideouts. Ground and helicopter-borne elements of the ANP are being supported by local police and units of the Gendarmerie Nationale (al-Dark al-Watani), Algeria’s rural police force. The elimination of AQIM elements in Algeria is complicated by the movement’s policy of operating in cells of 4-5 fighters, thus reducing the risk posed to the organization’s survival by any one encounter with security forces (El Watan [Algiers], April 14).

It was reported that a ground operation supported by helicopters in the forests of Bordj Bou Arreridj province had eliminated 12 terrorists and captured a number of others. Algerian authorities are using DNA evidence to identify the dead militants (El-Khabar [Algiers], April 14; L’Expression [Algiers], April 15).

Lack of surveillance aircraft, heavy transport, jet-fighters and even helicopters in many of the Sahel/Sahara nations inhibits counterterrorist efforts conducted over a vast and often inhospitable region. In this regard, Algeria, one of the few area nations with a large and capable air force, has been urging Nigeria to add its air force to the campaign against AQIM. Algiers has informed Abuja that AQIM Amirs have begun recruiting in north Nigeria (Jeune Afrique, April 17). Both Nigeria and Senegal, another proposed member of the alliance, are expected to attend the next meeting of regional security officials (El-Khabar [Algiers], April 7).

After irritating Algerian leaders by including that nation on the American terrorist blacklist following the failed Christmas Day attack aboard an American airliner by a Nigerian would-be bomber, Washington has been making major efforts of late to reassure Algeria it is a vital and trusted part of America’s counterterrorism strategy. A recent visit by FBI officials was followed on April 7 by a visit from U.S. Attorney-General Eric Holder to sign a security agreement covering counterterrorism, organized crime, drug enforcement and judicial cooperation (Algerian Radio, April 7).

Developing Regional Counterterrorist Strategies

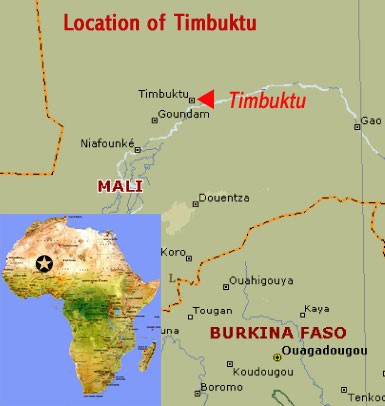

It was announced on April 20 that a military summit in the southern Algerian oasis town of Tamanrasset had agreed to form a “Joint Operational Military Committee” with headquarters in that town to deal with the problem of AQIM and gangs of drug traffickers who make use of poorly defined or guarded borders. While it was known that Algeria, Mali, Niger and Mauritania were considering such a move, the announcement contained the surprising news that Libya, Chad and Burkina Faso had also joined the initiative. The new joint command, to begin work by the end of April, will include officers from each of the participating Sahara/Sahel nations. Morocco, a rival to Algeria for influence in the region, appears to have been deliberately left out of the new formation. Many details of the initiative have yet to be revealed, including the command’s financing, the composition of joint military forces (if any) and whether joint forces would be permitted to cross borders in pursuit of terrorists (Afrol News, April 20).

The summit of military commanders followed hard on earlier meetings between the foreign ministers and the intelligence chiefs of the seven Sahara/Sahel nations that began on March 16. A summit of regional heads-of-state is expected to follow. Algeria has played the leading role in developing military cooperation in the region; the Algerian Ministry of Defense described the meetings as a means of defining “the ways and means capable of putting in place a collective and co-responsible strategy for fighting against terrorism and transnational crime.”

One motivation behind the rather rapid development of diplomatic and military cooperation in the region appears to be the desire of participating nations to avoid foreign [i.e. American] intervention in the region to deal with AQIM. One of those present at the military summit told a Malian daily that “There was a call on Algiers to act quickly to counteract the interference of foreign forces to act on our behalf. We are strongly against any foreign interference” (Le Républicain [Bamako], April 15). The United States will begin military maneuvers in Burkina Faso in early May, with the participation of roughly 400 troops from Burkina Faso, Mauritania, Chad, Niger, Mali and Senegal. Algeria declined an invitation to participate after expressing concerns about the U.S.-led military exercises (El Khabar, April 15). Though many of the participating nations are eager to receive U.S. arms, funds and training, none have volunteered to host AFRICOM, the new U.S. military command for Africa, which remains based in Germany.

Tackling the Ideological Basis of Extremism

Algeria has also taken steps to confront the religious and ideological foundations of AQIM and other extremist movements. The Algerian Ministry of Religious Affairs and Endowments is hosting a meeting this month of regional religious leaders and scholars to focus on grounding regional religious practice on the Maliki madhab, one of the four schools of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence. The Maliki school is widely followed in north and west Africa, and a renewed emphasis on its merits will be offered as a means of deterring the infiltration of “foreign” (i.e. Salafist) forms of Islam that espouse takfiri practices (the declaration of other Muslims as apostates deserving of death) that form the ideological foundation of terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda. The conference is intended to examine “the dimensions of intellectual security, its consequences and the reasons that led to the appearance of negative ideas that had fatal consequences for many countries, including Algeria,” according to Minister of Religious Affairs Bouabdellah Ghlamallah (Magharabia, April 6).

Algeria is also seeking technological solutions to the terrorist threat. The recent introduction of sophisticated explosives detectors in the ports of Algiers, Annaba and Oran have resulted in the seizure of 50 tons of TNT as well as 300 tons of chemical fertilizer intended for use in bomb-making. Combined with new restrictions on the sale and distribution of certain chemicals and fertilizers, the inspection of cargos with the new detectors has made it difficult for terrorist groups in Algeria to obtain the necessary raw materials needed to manufacture bombs (El Khabar, April 7).

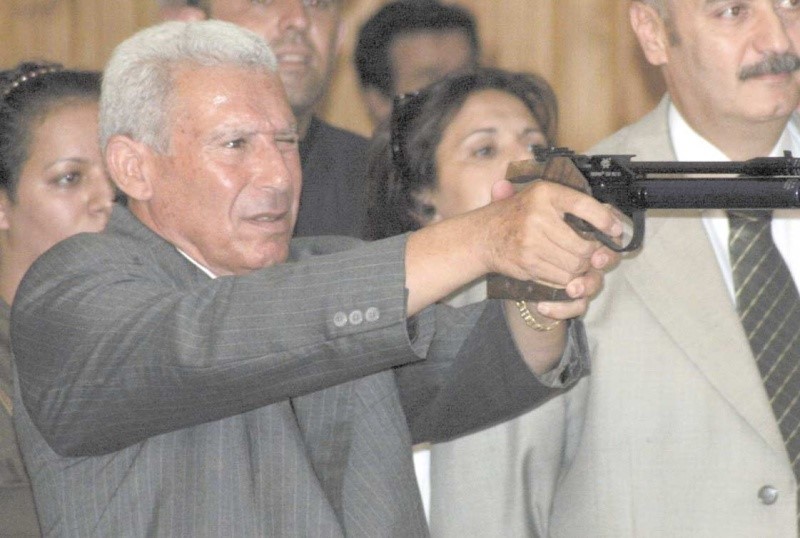

Assassinated DGSN Chief Ali Tounsi

Assassinated DGSN Chief Ali Tounsi

A Surprising Setback for Algeria’s Security Efforts

Algeria’s counterterrorist efforts suffered an unforeseen blow in late February when Ali Tounsi, the head of Algeria’s Direction Générale de la Sureté Nationale (DGSN – Directorate General for National Security) was murdered in his office by a close friend and partner in the counterterrorism effort, Colonel Chouieb Oultache (a.k.a. “The Mustache”). Described by one source as “the architect of the modernization of the national police, the dreaded adversary of radical Islamists [and] the pet peeve of organized crime,” Ali Tounsi was a career security agent who left school in 1957 to join the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) in the independence struggle against France (Jeune Afrique, March 14). He was particularly adept at undercover work, but was retired in 1988 before the government asked him to return to active service in the early 1990s to combat the growing Islamist insurgency. His assassin, Chouieb Oultache, was chief of the police air unit, a formation he was largely responsible for creating. It was reported that Oultache learned he was about to be investigated on charges of embezzlement on his way to a meeting at Tounsi’s office. No one else was present at the meeting, where the two men apparently argued before Oultache pulled his service weapon and fired three bullets into Tounsi’s head. Shaykh Ali bin Hajj, the deputy leader of the banned Front Islamique du Salut (FIS – Islamic Salvation Front), issued a statement after al-Tounsi’s murder calling for reform in the Algerian security services. The Islamist leader claims the security services of the Arab world are consistently engaged in activities forbidden by Islam and international law:

In most dictatorial regimes, only those who are involved in corruption, violations, torture, allegation of false charges against their colleagues, and those who flatter their masters are promoted to higher ranks in the security apparatus. In short, those who are good for carrying out dirty missions (Media Commission of Shaykh Ali bin-Hajj, March 10).

Ali bin-Hajj especially called for the regime to avoid appointing military men to head the nation’s security services. The two individuals considered most likely to succeed Ali Tounsi are General Sadek Ait Mesabh and Colonel Muhammad Boutouili, both of the Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité (DRS – Directorate of Research and Security) (Tout sur l’Algérie, April 12).

This article first appeared in the April 22, 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor