Andrew McGregor

June 28, 2012

As Tuareg rebels battle radical Islamists with heavy weapons for control of the northern Mali city of Gao, Mali and the other 15 nations of the Economic Community of West African States(ECOWAS) are planning a military offensive designed to drive both groups out of northern Mali in an effort to re-impose order in the region and prevent the six-month old conflict from destabilizing the entire region. So far, however, operational planning has not been detailed enough to gain the approval of the UN Security Council for authorization of a Chapter Seven military intervention, leaving ECOWAS and the African Union with the option of delaying the campaign or proceeding without UN approval.

An ECOWAS Intervention Force

ECOWAS maintains that a military intervention would be a last resort if talks hosted by the ECOWAS-appointed mediator (Burkino Faso President Blaise Compaore) should fail, but with negotiations in Ouagadougou going nowhere and divisions between the formerly allied rebel groups erupting into open conflict in northern Mali, there will be inevitable pressure to step up preparations for a military intervention. One obstacle to deployment so far has been the absence of a formal invitation from Malian authorities, though there has been discussion within ECOWAS of launching a military intervention without Mali’s consent (PANA Online [Dakar], June 9; Le Combat [Bamako], June 20).

MNLA Fighters in Northern Mali

ECOWAS has explicitly rejected the rebels’ “so-called declaration of independence” and has stated that it will “never compromise on the territorial integrity of Mali” (PANA Online [Dakar], May 30). Though the Islamists have agreed to talks, the mediators in Ouagadougou have insisted the largely Tuareg Islamist Ansar al-Din movement of Iyad ag Ghali sever all ties with al-Qaeda before talks can proceed, a move that seems most unlikely at this point (AFP, June 18; for a profile of Ag Ghali, see Militant Leadership Monitor, February 2012). Ansar al-Din spokesman Sena Ould Boumama has warned that his movement “will fight ECOWAS if it engages us in northern Mali” (al-Akhbar [Timbuktu], n.d., via Le Politicien [Bamako], June 7).

Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Niger and Nigeria are all expected to contribute troops to the mission if it receives authorization. Mauritania, which has conducted cross-border counter-terrorist operations in Mali in the past but is not a member of ECOWAS, has only expressed its “availability to join common efforts” to resolve the crisis (AFP, June 4). The ECOWAS intervention, which is projected to consist of 3,270 men, will have to stabilize southern Mali before it can effectively restore control of the north to the Bamako government.

Algeria, with a capability for desert operations and a powerful military with decades of combat experience, has been urged by some Western and regional nations to take a leading role in any intervention, but appears reluctant to provide ground forces. Algeria’s participation is widely viewed as key to the success of any military intervention. Earlier this month, Algerian intelligence chief General Muhammad “Toufik” Mediène described a potential Algerian role consisting of intelligence provision and airlifts of necessary materiel from Tamanrasset and Reggane (Jeune Afrique, June 14). Algeria’s main condition for participation will likely be the complete absence of Western troops from the campaign, particularly French forces.

Niger’s president Mahamadou Issoufou is a strong supporter of the intervention and claims to have information regarding the presence of Afghan and Pakistani instructors working with the Islamists in northern Mali, but has not shared the details publically (France 24, June 7. With a large and often restless Tuareg minority in northern Niger, Issoufou has much to lose by allowing the creation of an independent state in northern Mali. The Niger Foreign Minister has stated that “the military option is the only one” for Mali (Le Politicien [Bamako], June 7).

The Government in Bamako

In post-coup Bamako, the lack of political leadership remains a major stumbling block to resolving the crisis. Dissatisfaction is growing in many quarters with the prevarications of Transitional Government Prime Minister Cheick Modibo Diarra and his continued opposition to a foreign military intervention (22 Septembre [Bamako], June 19). Mali’s 70-year-old transitional president, Dioncounda Traoré, was attacked by pro-coup demonstrators in Bamako on May 22, enduring injuries that forced his evacuation to a Paris hospital (AFP, June 5). Complicating matters is the continued presence of coup-leader Captain Amadou Haya Sanogo, despite the ECOWAS-ordered dissolution of Sanogo’s Comité National pour le Redressement de la Démocratie et la Restauration de l’Etat (CNRDRE) on June 7.

In return for ending his destructive putsch and agreeing to step aside for a transitional government, Sanogo has been rewarded with official former head-of-state status, a generous monthly allowance, a prominent residence and two vehicles. This decision came despite the opposition of ECOWAS, which wanted to return Sanago to a subordinate position in the military (L’Indépendant [Bamako], May 23; Le Combat [Bamako], June 12). The 39-year-old American-trained Sanogo is reported to rarely leave his well-guarded residence inside the Kati military base outside of Bamako. In a recent interview, Sanogo insisted that if the Army were given the means, it “would recover the north in a few days” (Jeune Afrique, June 9). Members of the CNRDRE, including Sanogo, continue to wield influence by having formed the Comité militaire de suivi de la réforme des forces de défense et de sécurité (CMSRFDS) on June 12 to absorb the CNRDRE, though the new committee will allegedly act in only an advisory role (Le Pays [Ouagadougou], June 14; L’indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], June 18).

Supporters and opponents of the March military coup have organized themselves into two fronts: the pro-putsch Coordination of the Patriotic Organizations of Mali (COPAM) and the anti-putsch Front for Safeguarding Democracy and Republic (FDR), though in a positive sign, the two groups have been meeting for discussions of Mali’s political future (Le Republicain [Bamako], June 18). COPAM took advantage of the attack on Dioncounda Traoré to hold a convention to advance the name of Captain Sanogo as the new transitional president, which only created further suspicion as to the motives and identity of those behind the attack on the transitional president (L’Indépendant [Bamako], May 23, May 25; Le Combat [Bamako], June 2; Info Matin [Bamako], June 7). Since then, several leaders of COPAM have been jailed while others appear to have left the country. Nonetheless, a pro-Sanogo radio station, Raio Kayira, urges opposition to ECOWAS “meddling” in Malian affairs and hosts regular calls for the death of Dioncounda Traoré and former members of the government (Jeune Afrique, May 30).

Clashes between the MNLA and Ansar al-Din

On May 26, Ansar al-Din and the secular Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) announced their merger as the Transitional Council of the Islamic State of Azawad (L’Essor [Bamako], May 30). However, by June 1, the MNLA had issued a new document declaring all provisions of the May 26 merger agreement “null and void” (AFP, June 1). Mossa ag Attaher, a MNLA spokesman, admitted that the group had made a mistake in drafting the agreement: “[We] accepted the idea of an Islamic State but it should have been written that we will practice a moderate and tolerant Islam, with no mention of Shari’a” (AFP, June 1).

A June 8 statement from Ansar al-Din expressed the movement’s disappointment with the MNLA’s withdrawal from the Gao Agreement, but stated the movement would continue alone if necessary: “Unfortunately we were surprised with the Nouakchott statement issued by the Political Bureau of the movement which stated its clear refusal of the project of the Islamic state… therefore the Jama’at Ansar Al-Din declares and ensures to the sons of its Islamic ummah [community] its adherence to the Islamic project.”[1] Clashes between the two movements were reported the same day in Kidal, resulting in the city being roughly divided between the two armed groups (AFP, June 8).

Though the short-lived agreement spoke of an “independent Azawad” nation, Ansar al-Din leader Iyad ag Ghali has since returned to his opposition to the establishment of a new state: “We are not asking for much: just the application of Shari’a law in the northern and southern regions. We are Malians and we are against the division of Mali… Anyone who does not lead the fight under our flag is our enemy and will be fought. Secularism is disbelief. Whoever is for a secular state is our enemy and will fought by all means” (Reuters, June 16).

While the MNLA were willing to agree to an Islamic State, their conception of a moderate and tolerant Islamic base quickly proved at odds with the Islamists of Ansar al-Din and the al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) splinter group, Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA), whose eagerness to begin lashing people for trivial offenses threatens to dissipate even the small popular support they may have enjoyed several months ago. Their numerous prohibitions and severe punishments have defied even the advice of the AQIM Amir, Abu MusabAbdul Wadud (a.k.a. Abdelmalek Droukdel), who used a May 23 audiotape release to warn the Islamists: “It is a mistake to impose all the rules of Islam at once on people overnight… So, for example, shutting down places of drugs, liquors and immoralities is something that they can seek to do now without delay, but the implementation of the just punishment is the responsibility of the Shari’a legislators and should come gradually” (Sahara Media [Nouakchott], May 23).

Face-to-face negotiations between Iyad ag Ghali and MNLA leader Muhammad ag Najim in Gao have had little success, as the gulf between the freedom and independence sought by the Tuareg of the MNLA and the strictly regulated future offered by the Salafists of Ansar al-Din is too great (Le Republicain [Bamako], May 30). Ag Ghali, who is reported to now speak only Arabic and wishes to be known by the Arabic name of Abu Fadil, is insistent on giving space to AQIM in the new state of Azawad, a breaking point in negotiations with the MNLA (Jeune Afrique, June 9).

Prior to the current fighting in Gao, a major clash between the MNLA and Ansar al-Din occurred in Timbuktu on June 13. Other confrontations have been reported in northern towns where residents have demonstrated in favor of the MNLA and against the Islamists (L’Essor [Bamako], June 19; AFP, June 13). The Malian government is also preparing a file for submission to the International Criminal Court (ICC) concerning the slaughter of disarmed prisoners at Aguelhok in late January,an action claimed by Ansar al-Din during a joint operation with the MNLA(Le Combat [Bamako], June 12). In its public statements and attitudes, it is clear the MNLA is now trying to distance itself from the Islamist factions, particularly with possible ICC prosecutions looming if ECOWAS is successful in retaking northern Mali (Info Matin [Bamako], June 12).

Dissension in the North

There are many indications that those northern Malians who have not fled the country outright have already tired of Islamist rule. By some reports, the situation in Gao (co-administered by the MNLA) is becoming critical, with a lack of food, water, electricity and currency (L’Essor [Bamako], May 23). In Kidal, youth and women tired of Ansar al-Din’s social restrictions gathered to display their opposition to the movement with slogans, public smoking in defiance of the ban on tobacco use, and stone-throwing by the women, who removed their Islamist-decreed veils after Ansar al-Din elements retreated in damaged vehicles (Le Republicain [Bamako], June 7; Le Combat [Bamako], June 7).

In the town of Bourem, MUJWA outraged local residents by opening three prisons for those “caught doing sin,” one for men, one for women and one for children. In Douentza (Mopti Region), the power supply has been shut down for lack of fuel and MNLA fighters are reported to be looting local homes (L’Essor, June 12, June 19). In the town of Goundam, two-thirds of the population of 12,000 has left, while the remaining young men often have verbal confrontations with the rebels that result in their arrest (L’Essor [Bamako], June 7).

The Malian Army

Since 1991, the Malian military has suffered from underfunding, nepotism, corruption, under training, poor pay and a failure to maintain its aircraft and armor. Chronic demoralization is the result of purges of the officer corps, attempts to integrate former Tuareg rebels with loyalist troops and being required to operate in unfamiliar desert terrain with a lack of intelligence, equipment or ammunition (Jeune Afrique, June 17). Malian troops suffered greatly in the northern campaign earlier this year from an almost total lack of air support from the much-decayed Malian air assets.

On a recent visit to the Amadoui Cheickou Tall military base, Malian Prime Minister Cheick Modibo Diarra told government troops: “If God gives me the time and strength to liberate the country, I promise that my government will not spare any effort to create a strong, modern, efficient and effective army, an army that frightens, an army that brings peace” (L’Essor [Bamako], June 5). Where the money will come from to support a revival of the military is uncertain; the economic disaster that followed the coup d’état has resulted in the state budget being reduced from FCFA 1400 billion to FCFA 870 billion (Le Combat [Bamako], June 4). Even the removal of ECOWAS sanctions has failed to renew capital flows into Mali until the army returns to its barracks and a new, elected government is formed.

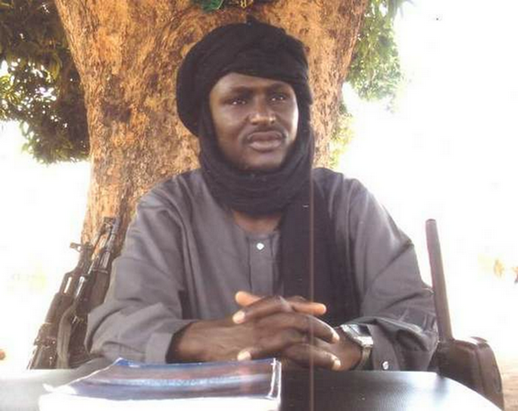

Colonel Ould Meydou

Colonel Ould Meydou

Malian fortunes in the north will rest in the hands of three senior officers known for their fighting skills and distaste for barracks life: Colonel al-Hajj Gamou, a Tuareg, Colonel Ould Meydou, anArab, and Colonel Didier Dakuo, a southerner. Gamou and Meydou met with Algerian authorities last month regarding future operations in northern Mali (AFP, May 24). Colonel Meydou narrowly escaped the military revolt at the Kati military base that started the coup and took refuge in Mauritania, where he says he is prepared to return to the field with 1,000 men of the Arab militia he commands (Jeune Afrique, June 17).

Using deceit, Colonel Ag Gamou was able to escape from northern Mali into Niger with his command intact when the rest of the Malian Army collapsed. Though presently disarmed, some 600 pro-state Tuareg fighters under his command are awaiting redeployment into northern Mali at a military base near Niamey (Independent [London], May 10; L’Indépendant [Bamako], June 18).

In addition to the desert-fighting skills of these militias, roughly 2,000 regulars with ten armored vehicles under Colonel Dakuo are available in the Mopti Region town of Sévaré, close to the southernmost area occupied by the rebels. For now, this total group of roughly 3,000 to 4,000 men represents all the forces the Malian Army can count on. They will face rebels equipped with superior Libyan arms supplemented by vast stocks of military materiel seized from the Malian Army earlier this year. Nearly all the Army’s Russian-made assault tanks have been destroyed or disabled.

Mali’s military will be handicapped in their re-conquest of the north by the absence of its elite unit, the “Red Beret” parachute commando regiment of some 600 men under the command of Colonel Abidine Guindo. The regiment, which doubled as the presidential guard, was officially disbanded by the putschists after it remained loyal to ex-President Amadou Toumani Touré and succeeded in spiriting Touré out of the country before he could be arrested. A failed counter-coup led by the “Red Berets” on April 30 complicated matters further, with members of the regiment now being put on trial for opposing the new government.

The Role of Militias

The Arabs of northern Mali have largely remained loyal to the concept of a secular and unified Malian state and have no wish to come under Tuareg rule, whether secular or Islamist. An armed branch of the Arab opposition, the Front national de libération de l’Azawad (FNLA, also known as al-Jabhah al-Arabiya, “the Arab Front”), has vowed to wage war “for the liberation of Timbuktu and the independence of our territory,” while maintaining a secular, non-secessionist and non-Islamist identity (AFP, June 5; L’Essor [Bamako], June 7).

Another group is the Front de libération du Nord-Mali (FLNM – National Front for the Liberation of Northern Mali), formed on May 28 as an umbrella group for the largely Black African Songhai and Peul/Fulani Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso militias, which have a strong anti-Arab and anti-Tuareg character (Le Republicain [Bamako], May 30; for the Ganda Koy, Ganda Iso and other Malian militias, see Terrorism Monitor, April 20). The militias, which have a notorious reputation for violence against civilians, say that the peace talks in Burkina Faso do not concern them as negotiations should follow military action (VOA, June 26).

A Timbuktu militia allegedly formed from the Songhai and Tuareg ethnic groups has vowed to expel the Islamists from that city. According to Hamidou Maiga, a former officer in the Malian Army, the Mouvement patriotique de résistance pour la libération de Tombouctou (MPRLT) “will engage in military action against the invaders until they leave” (AFP, June 7).

Retaking Northern Mali

Malian military sources have indicated a plan to retake the north would begin with the liberation of Douentza in Mopti region. Military operations are projected to employ irregular but unreliable units such as the Ganda Iso and Ganda Koy militias (Le Politicien [Bamako], June 7). A drive from the south could be accompanied by the reinsertion of Colonel Ag Gamou’s Tuareg militia from the southeastern border with Niger. The number of rebels is uncertain, but the MNLA claims to have 10,000 men under its command, while the Ansar al-Din is estimated to have 500 and MUJWA to have some 300. Driving these groups out of the cities of Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu might require challenging urban warfare, but dealing with a guerrilla campaign in the desert wilderness could prove even more difficult.

Washington and Paris would undoubtedly be called on to provide intelligence (particularly aerial surveillance), logistical support and financial support. If Algeria prevents the use of American or French special forces for gathering operational intelligence on the ground, it might deploy its own Groupe d’Intervention Spécial (GIS) for this purpose.

The deployment of air assets, whatever their source, will be complicated by the possible rebel possession of anti-aircraft weapons from Libya’s armories. Such weapons appear to have been used by Ansar al-Din on June 15 against two unmarked planes (likely American surveillance aircraft) flying over Timbuktu (AFP, June 17).

Conclusion

While both Ansar al-Din and the MNLA are engaged in talks in Burkina Faso, it is safe to say that time is running out for a negotiated solution. The crisis in Mali and the outflow of refugees is destabilizing the entire region. There is also no desire either regionally or internationally to allow the further entrenchment of terrorist groups in the area such as AQIM or MUJWA, neither of which are involved in negotiations or any other effort to restore order to northern Mali. However, the opposition of Algeria to the involvement of Western militaries (on the ground at least) and a general Western reluctance to become heavily involved in such efforts after the Libyan debacle will ultimately leave such efforts in the hands of ECOWAS. However, this organization can deploy only a limited number of troops from a handful of countries with a limited history of cooperation in the field. The use of different languages, arms and communications systems will not enhance the efficiency of a West African intervention force, and the absence of accurate intelligence could prove fatal in a confrontation with experienced, determined and well-armed rebels on their home turf. Without substantial cooperation and support from Algeria or Western militaries, the small composite force of roughly 3,300 men envisaged by ECOWAS may experience many of the same setbacks experienced by the shattered Malian military earlier this year. While growing divisions amongst the Malian rebels may seem to present an opportune time for intervention, any military defeat suffered as the result of an over-hasty deployment could rock the political foundations of West African nations such as Nigeria that are enduring bloody insurgencies of their own.

Note

1. Sanda Ould Bouamama, Spokesman of Jama’at Ansar al-Din, “Statement from Jamaat Ansar Al-Din about the MNLA repealing of the Gao agreement,” Timbuktu, June 8, 2012.

This article first appeared in the June 28, 2012 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

MNLA on the Move (Andy Morgan)

MNLA on the Move (Andy Morgan)