Andrew McGregor

August 7, 2014

Only weeks after Sunni jihadists in Iraq declared the establishment of an Islamic Caliphate covering parts of Syria and Iraq, Libya’s Ansar al-Shari’a movement has declared an Islamic Emirate in eastern Libya after driving government forces and their allies from the city of Benghazi. The defeat of the strongest pro-government forces in eastern Libya has provided the Islamists with an impressive victory, but Ansar al-Shari’a and its allies are still struggling to obtain the support of Benghazi’s urban population and the powerful tribes dwelling in its hinterland.

The Libyan Emirate in the Modern Era

As the provinces that eventually formed modern Libya began to fall to British and French military forces following a string of defeats suffered by Italy, the colonial power in Libya, there were several abortive attempts to create a modern Emirate in eastern Libya. In anticipation of post-war independence in return for supporting the Allied cause, the Libyans agreed to the formation of a joint Tripolitanian-Cyrenaican Emirate with Sayyid Idris al-Sanusi as leader in 1940 (the third province, Fezzan, remained under French military administration from 1943 to 1951). This plan, however, began to disintegrate after liberation from Italian occupation in 1943 as the two Libyan provinces jostled for control of the new state. Sayyid Idris foresaw the emergence of Britain as the main power-broker in a post-colonial Libya (unlike the Tripolitanian leaders, who had incorrectly foreseen an Axis victory) and raised five battalions of the “Libyan Arab Force” to assist Allied operations in the North African desert campaign. A 1945 U.S. plan for a Cyrenaican emirate under British and Egyptian supervision failed to gain support, but in 1949 Britain decided unilaterally to create a Cyrenaican emirate under the leadership of Sayyid Idris, with foreign affairs, defense issues and military bases all remaining under British control. By the time independence arrived in 1951, plans for an emirate had been abandoned in favor of a federal constitutional monarchy with a bicameral parliament. [1]

Ansar al-Shari’a in Libya

The Islamist militia, established in post-revolutionary Libya in 2012, has a power-base in the eastern cities of Derna and Benghazi. It was in the latter city that the movement was deeply implicated in the September 11, 2012 attack on the American consulate. Ten days later, the group was driven from Benghazi by mass protests, but by March 2013 it was back in Benghazi, this time with a greater emphasis on providing social services to city residents.

New tensions began to arise in Benghazi in June, when General Haftar’s forces began launching attacks on armed Islamist militias in Benghazi and Derna and preliminary results of the parliamentary election revealed a massive rejection of Islamist candidates (all seats were contested on an individual rather than party basis). Afraid of being shut out of the political process, the Islamist militias in Benghazi (including Ansar al-Shari’a, the Libya Shield Brigade no. 1, the 17 February Brigade and the Rafallah Sahati Brigade) united under an umbrella structure known as the Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries (Daily Star [Beirut], August 1). Many of these groups are affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood stronghold in Misrata. The restructuring at first helped limit Haftar’s successes in the region before allowing the united Islamists to push back against Haftar’s outnumbered “National Army” and its allies.

In June, Ansar al-Shari’a leader Muhammad al-Zawahi reasserted his movement’s opposition to both the government and democracy in general, while warning the United States to forget about military intervention in Libya in view of America’s “despicable defeats in Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia,” promising it would “face worse from Libya” (BBC, June 13).

Colonel Wanis Bu Khamada

Colonel Wanis Bu Khamada

Expelling al-Sa’iqah

On July 29, Ansar al-Shari’a and its allies in the Shura Council mounted a bold attack on the Benghazi base of the pro-government al-Sa’iqah (Thunderbolt) Special Forces, an elite unit led by Colonel Wanis Bu Khamada that is allied to Libyan Major-General Khalifah Haftar, but not under his direct command. Haftar’s ongoing Operation al-Karamah (Dignity) is an attempt to eliminate Islamist militias in Libya and restore order in the lawless cities. The Islamist attack succeeded in taking the main camp of al-Sa’iqah, located in the Bu-Atni district of Benghazi.

With the capture of most of the city (excluding a part of the airport still controlled by Haftar’s forces), Ansar al-Shari’a leader Muhammad al-Zahawi declared on July 30 that “Benghazi has now become an Islamic Emirate” (Radio Tawhid, July 30; al-Jazeera, July 31). Haftar insisted that his forces had only conducted a “tactical withdrawal” from parts of Benghazi and that the Islamist claimi to control the city was “a lie”: “There is a difference between control and looting and thefts. After the Special Forces withdrew from the Special Forces’ camp, [the Islamists] tried to steal what they could steal” (al-Arabiya, July 30; July 31). Since mid-July, the Shura Council has taken five military bases in the Benghazi region, including the main Special Forces camp in Benghazi, overcoming strikes from Libyan jet-fighters and helicopters in their advance (al-Jazeera, July 31). Benghazi’s main police station was also abandoned after being shelled by Shura Council forces.

Ansar al-Shari’a Fighters Pose After Taking the Libyan Special Forces Base

Ansar al-Shari’a Fighters Pose After Taking the Libyan Special Forces Base

Losses were heavy, with at least 78 soldiers killed in the assault on the base. Large quantities of arms, rockets, ammunition and even armored vehicles were seized from the stockpiles of the Special Forces, AFP/al-Akhbar [Beirut], July 30; Daily Star [Beirut], August 1). A video released soon after the battle showed Ansar al-Shari’a commander Muhammad al-Zawahi touring the battered Special Forces camp with Libyan Shield Brigade commander Wissam Bin Hamid, who declared: “We will not stop until we establish the rule of God.” [2] Bin Hamid no doubt took satisfaction in having expelled al-Sa’iqah, having been driven from his own headquarters in June 2013 by Special Forces units.

A Libyan National Army spokesman, Colonel Muhammad Hijazi, denied rumors of differences between Colonel Bu Khamada and General Haftar, adding that the withdrawal of al-Sa’iqah from its Benghazi base was “a military strategy. We are fighting against international intelligence organs like the Qatari and Turkish intelligence services” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, August 1).

Following the Islamist victory, Muhammad Sawwan, the leader of Libya’s Hizb al-Adala wa’l-Bina (Justice and Construction Party, the political arm of Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood), condemned Haftar’s Operation Dignity as armed interference with the political process and insists the poor showing by Islamists in parliamentary election results has nothing to do with the violence in Benghazi and Tripoli: “The parliamentary elections were held on the basis of the individual system. Therefore, talking about progress of one current and the defeat of the other is baseless” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, August 1).

A Libyan National Army spokesman, Colonel Muhammad Hijazi, denied rumors of differences between Colonel Bu Khamada and General Haftar, adding that the withdrawal of al-Sa’iqah from its Benghazi base was “a military strategy. We are fighting against international intelligence organs like the Qatari and Turkish intelligence services” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, August 1). There is a general belief in the forces allied to Haftar that the Islamists are materially and politically supported by Qatar and Turkey. However, despite the defeat, Colonel Bu Khamada insisted that his forces “still have the capacity to repel any attack on state institutions” (Al-Ahrar TV, August 2).

The Fallout

The Shura Council’s offensive forced the cancellation of a meeting of the new parliament to be held in Benghazi on August 4, forcing it to meet in Tobruk instead (BBC, July 30; AP, August 6). The new parliament immediately issued an order for an unconditional ceasefire in Benghazi and Tripoli (where similar clashes are underway) and promised, without the force to carry it out, that action would be taken against any group that failed to observe the ceasefire (Libya Herald, August 7).

While Haftar’s ground troops failed to reoccupy military facilities that had been abandoned after looting by the Islamists, his air assets launched air strikes against the compound of a Chinese construction company in Ajdabiya that had been taken over by Ansar al-Shari’a forces (Libya Herald, August 1). Haftar’s National Army has offered to protect further civilian demonstrations in Benghazi, though it is not clear how this would be possible without a presence in Benghazi (Libya Herald, August 1).

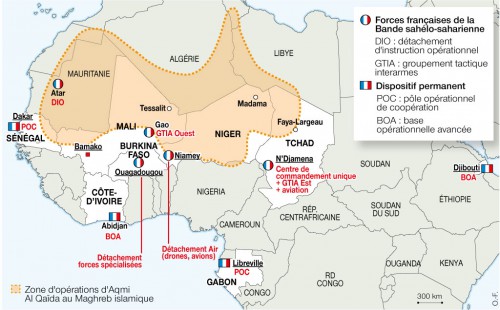

While there is some consensus that foreign jihadists are arriving in Libya in substantial numbers, exact figures are impossible to obtain. According to General Haftar, the Islamists “are aided by renegade groups like them from all around the world. Unfortunately, in the absence of a government or police, those groups use this opportunity to come from Algeria, Mali, Niger, and even elsewhere. They even come from overseas. Many of them came from Afghanistan and many other areas” (al-Arabiya, July 30).

For now, the oil-fields of eastern Libya remain in production, but as part of a much diminished national rate of 500,000 barrels per day (b.p.d.), as opposed to a normal 1.4 million b.p.d. (Reuters, July 29). Oil accounts for some 95% of state revenues in Libya.

Conclusion

Ansar al-Shari’a’s declaration of an Emirate was met with popular anger rather than acclaim, with large crowds of angry civilians taking to the streets of Benghazi. The protesters ignored a pair of warning volleys from Ansar militiamen and forced the gunmen from the Jala’a hospital it occupied in Benghazi, tearing down the black-and-white rayat al-uqab banner also used by the Islamic State and al-Qaeda and replacing it with a Libyan flag (Libya Herald, July 30). There were also reports that the demonstrators torched the home of Ansar al-Shari’a leader Muhammad al-Zahawi (al-Sharq al-Awsat, July 31). The failure of forces belonging to Haftar’s Operation Dignity to capitalize on this unexpected civilian triumph allowed the Islamists to re-assert themselves in an even stronger position in Benghazi by July 31.

Haftar’s National Army, still without official recognition from the government, has managed to gain the allegiance of a number of pro-government armed groups (some of which are probably reconsidering their position at this point), but has failed to get the all-important support of Libya’s tribes, which continue to withhold their commitment to one side or the other of the ongoing conflict. For now, both Ansar al-Shari’a and Haftar’s National Army claim to be receiving new weapons, promising another round of the urban warfare that is beginning to inflict severe damage on some neighborhoods of Benghazi (Libya Herald, July 29). Unless and until General Haftar and/or the new Libyan government can bring both trained troops and the nation’s influential tribes on board with the anti-Islamist program, Libya will remain a gathering point for international jihadis and Libyan fighters returning from the battlefields of Syria and Iraq, something the defeated forces allied to the national government may find themselves powerless to prevent.

Notes

1. Alison Pargeter, Libya: The Rise and Fall of Qaddafi, Yale University Press, 2012, Chapter 1; John Oakes, Libya: The History of a Pariah State, History Press, Stroud, Gloucestershire, 2011, Chapter 6.

2. See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHUDbffJloo

This article first appeared in the August 7, 2014 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

Grand Mufti Shaykh Shawqi Ibrahim Abd al-Karim Allam

Grand Mufti Shaykh Shawqi Ibrahim Abd al-Karim Allam Grand Mufti Shaykh Abd al-Aziz al-Ashaykh

Grand Mufti Shaykh Abd al-Aziz al-Ashaykh