Andrew McGregor

Citation:

“Radical Islamic Groups in Central Asia and their External Contacts,” in: Central Asia and the Northern Caucasus: Salafis, Shi’ites, and Jihadists, al-Mesbar Studies and Research Center, Dubai, 2014, pp. 105-126 (Arabic language).

Introduction; Modern Origins of Islamic Militancy in Central Asia

The Islamist movement in Central Asia has its modern origins in the post-Soviet environment of Central Asia’s Ferghana Valley, a traditional cultural and economic meeting point now divided by the national borders of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. A growing youth population, high unemployment rates and stagnant economic conditions have created conditions in the Ferghana usually associated with the growth of Islamist militancy, but effective (though heavy-handed) security measures and a general lack of resonance for the Islamist project means the region has avoided the massive sectarian clashes predicted after the emergence of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) [1] and its predecessors in the 1990s.

The Salafist approach to Islam favored by most Islamist militant groups in the region is mixed in Central Asia to a large degree with Deobandism, a pan-Islamic revival movement developed in India as a reaction to 19th century British imperialism. Deobandism became politically radicalized in modern Pakistan and came to be the basis of the Taliban system in Afghanistan

The Salafist approach to Islam favored by most Islamist militant groups in the region is mixed in Central Asia to a large degree with Deobandism, a pan-Islamic revival movement developed in India as a reaction to 19th century British imperialism. Deobandism became politically radicalized in modern Pakistan and came to be the basis of the Taliban system in Afghanistan

Salafist Islam and Islamist militancy initially made inroads in Central Asia in the dying days of the Soviet empire as residents of the region began to explore their Islamic heritage in the interests of reasserting local identities in a post-Soviet and possibly post-secular world. Scholarships to Salafist religious/educational institutions helped introduce reformist Islam to Central Asia through the medium of its own young scholars. However, conditions have changed since the days when Central Asia emerged from seven decades of official atheism and the militants’ message does not seem to have the same penetration it once did, even in the face of continued drivers of radicalism such as poverty, lack of access to education and authoritarian repression.

Adolat, the predecessor to the IMU, established Shari’a law under the direction of the late Tahir Yuldash (formerly Yuldashev; a.k.a. Muhammad Tahir Faruq; 1967 – 2009) in the town of Namangan in the Uzbek part of the Ferghana Valley in 1991. [2] Adolat was eventually repressed by the Uzbekistan government, but Yuldash and several other prominent members escaped to Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, where they formed the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan as a means of expelling the regime of Islam Karimov and founding an Islamic Caliphate that would eventually spread throughout the ex-Soviet republics of Central Asia. [3] There are reports that Yuldash travelled throughout the Gulf region in the 1990s, establishing funding conduits with sympathetic groups and individuals, including the Uzbek diaspora in Saudi Arabia, formed from survivors of the 1918-1928 anti-Soviet Basmachi Rebellion in Central Asia. [4] Yuldash also travelled to Turkey and Pakistan, attempting to gain the financial and material support of the intelligence services of those nations. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) is believed to have responded favorably to the IMU commander’s overtures. [5] The strong Saudi influence on the IMU appears to have had its origins in Tahir Yuldashev’s religious training and fundraising activities in the Kingdom.

A unit of roughly 100 to 200 IMU fighters under the leadership of commander Juma Namangani (a.k.a. Jumaboy Ahmadjonovich Hojiyev, a reputed former Soviet paratrooper in the Soviet war in Afghanistan) gained military experience fighting alongside Islamist factions in the Tajikistan civil war (1992-97) but found no place for the movement in the negotiated settlement of 1997, leading the movement to shift to bases in Afghanistan under the sponsorship of the Taliban. From there, the IMU launched its 1999-2000 campaign in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan which ultimately failed to achieve its goal of entering Uzbekistan and deposing President Karimov (the movement was also targeting the rulers of Kyrgyzstan at this point). Though the campaign was largely restricted to small-scale attacks and hostage-taking (including the commander of Kyrgyzstan’s Interior Ministry), the militants’ apparent better training and equipment reduced national security forces to chasing the group around the mountains and briefly caused alarm in regional capitals.

IMU Escape to FATA – A problem of relevance

The movement proclaimed its allegiance to Mullah Omar and the Taliban when the U.S.-led alliance invaded Afghanistan in late 2001. The IMU suffered a severe blow when Juma Namangani, its military leader and the architect of its surprising if ultimately multi-nation Central Asian campaign, was killed during an American bombing of pro-Taliban positions in Kunduz.

In an operational sense, the IMU never recovered from the death of Namangani, their unchallenged military commander. With his death passed the time when the movement could mount large operations that created serious concern in the capitals of the Central Asian republics. Under military pressure from the U.S. and its allies, the IMU left for the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Afghanistan in 2001, establishing themselves in the Wana region of South Waziristan.

Having escaped the U.S.-Northern Alliance offensive in Afghanistan, the movement took refuge in the Wana regin of South Waziristan, where they enjoyed the protection of local warlord Maulvi Nazir and the Ahmadzai Wazir until 2007, when they were expelled for offending local customs and behaving like “occupiers.” [6] The movement then intensified its alliance with a new patron from the Mahsudi rivals of the Ahmadzai Wazir, Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) leader Baitullah Mehsud, though some fighters appear to have joined the Taliban in Afghanistan or to have joined previous waves of disillusioned fighters in making a stealthy return home. During their residency in north-western Pakistan, many of the original members of the movement established successful farms and businesses as well as integrating into the local community through intermarriage. The IMU’s last confirmed operations of any significance in Central Asia occurred in 2004. The movement has claimed responsibility for attacks in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan in 2009-2010, but these claims seem more likely to have been an attempt to reassert some relevance for the movement in Central Asia.

The IMU’s gradual loss of purpose in its long exile from Central Asia is often reflected in reports that members of the movement frequently act as bodyguards for Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) leaders or as enforcers-for-hire in the FATA region. In December 2012, Federal Minister Shaykh Waqas Akram (Pakistan Muslim League-Q) told Pakistan’s National Assembly that Uzbek militants of the IMU were acting in league with various banned organizations in Punjab Province and were ready to carry out terrorist acts for a payment of $40,000. [7] The minister’s claims came only days after a devastating suicide attack by a squad of militants on Peshawar’s Bach Khan Airport on December 15. Though the attack was claimed by the TTP, authorities blamed Uzbek militants based on an examination of the remains of the attackers, the usual method used to generate body counts of alleged Chechens, Daghestanis, Uzbeks, Tajiks, Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic groups useful in framing local conflicts as internationally-generated threats to the state. [8]

A glimpse of the indigenization process experienced by the IMU in their Afghan/Pakistani exile can be obtained from a list of 87 IMU “martyrs” in 2011. 64 of the individuals hailed from Afghanistan, while only four came from Uzbekistan. The remainder originated in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Germany, Pakistan and Tatarstan (Russian Federation). [9] Analyst Jacob Zenn has pointed out that even “the IMU’s current ‘mufti’ (expert in Islamic law), Abu Zar al-Burmi, is an Urdu and Arabic-speaking Pakistani national of Burmese Rohingya descent with neither a trace of Uzbek blood nor proficiency in the Uzbek language.” [10]

While based in FATA, the IMU developed strong ties with TTP leader Baitullah Mehsud (killed by a U.S. drone strike on August 5, 2009) and his successor Hakimullah Mehsud (killed by a U.S. drone strike on November 1, 2013), for whom members of the group often acted as local enforcers. Tahir Yuldash was himself killed by an American drone strike in Pakistan in 2009. His successor, Abu Usman Adil, developed a relationship with Hakimullah Mehsud and his TTP deputy Waliur Rahman before he was also killed by a U.S. drone strike in April, 2012. The IMU is currently led by Adil’s former deputy, Usman Ghazi.

The Threat to Tajikistan

Soon after obtaining its independence from the collapsing Soviet Union in 1991, Tajikistan experienced a devastating civil war from 1992 to 1997 that killed roughly 100,000 people, displaced over a million more and provoked the loss of most of Tajikistan’s ethnic Russian and European population, which formed much of the country’s professional and administrative classes. The war pitted ethnic groups from the Garm and Gorno-Badakhshan regions who felt they were underrepresented in the regime of President Rahmon Nabiyev against groups from the Leninabad and Kulyab regions that had formed most of the ruling elite under Soviet rule. The disparate opposition eventually united under the banner of the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), an awkward coalition of liberal democrats and Islamists. By 1993 the Garmi and allied Pamiri Isma’ili Shi’a opposition forces were suffering from serious reverses on the battlefield and a violent campaign by government forces determined to drive Garmi and Pamiri civilians from Tajikistan. Both Garmi and Pamiri civilians and Islamist fighters took refuge across the border in Afghanistan, where the Islamist fighters received arms and assistance from ethnic Tajik Ahmad Shah Massoud, leader of the Northern Alliance military forces. The fighters also received religious training in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

A peace and reconciliation agreement in 1997 promised a new era, but in recent years the regime expelled most of the former armed Islamist opposition from their posts in the reconciliation government, adding to a wave of unrest fueled by corruption, economic failure and the revival of Islam after decades of Soviet repression. [11]

The Tajik Civil War has often been characterized as an Islamist-led rebellion against the central government, though there were other elements behind the violence that had more to do with tribal and regional rivalries than with religious observance. According to journalist Igor Rotar, who covered the struggle for Nezavisimaya Gazeta, “even the combatants themselves admit that the civil war was not so much a political struggle as a fight for power between different regional groups of Tajiks, who had not developed into a single nation at the time.” [12] Since then, however, there has been significant growth in Islamic extremism in northern Tajikistan, but few signs of involvement by external groups such as the IMU or the Afghan Taliban.

In 2009, Tajikistan launched Operation Kuknor (“Poppy,” loosely disguised as an anti-narcotics operation) against an armed group led by Lieutenant General Mirzo Ziyoev, a military commander of the Tajik Islamists in the civil war who was given a high military rank and his own paramilitary in the reconciliation that followed. Ziyoev was dismissed in 2006 and accused of having joined a unit of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) led by Shaykh

Nemat Azizov in June 2009, an assertion that was quickly denied by late IMU leader Tahir Yuldash, who suggested instead that Ziyoev had “fallen victim to intrigues of the government.” [13] Ziyoev was captured by security forces on July 11, 2009 and died later that day in crossfire between security forces and a group of militants that some Tajik authorities claimed were IMU gunmen, an assertion similarly denied by Tahir Yuldash. [14] A well-known guerrilla leader in the Tajik civil war, Shaykh Nemat Azizov was made leader of the Tavil-Dara division of Tajikistan’s Emergency Situations Ministry as part of the post-war reconciliation before he allegedly returned to armed opposition to the Tajik state, allegedly as an IMU commander, according to security services. [15] In July, 2009 a Daghestani individual made a televised confession that he and two other Daghestanis had joined Shaykh Nemat’s group. [16]

Some of the militants seized in 2009’s Operation Kuknor were part of a mass escape of 46 prisoners from a Tajik State Committee for National Security (SCNS) prison on August 25, 2010. A number of these militants were believed to have participated in an attack on a military convoy by an unidentified militant group in the Kamarob gorge of eastern Tajikistan, about 260 kilometers from Dushanbe, on September 19, 2010. The well-executed attack killed at least 28 soldiers (and possibly as many as 40) and left many more wounded. Though Tajik security officials identified Abdullo Rakhimov (better known as “Mullo Abdullo”) as the main suspect, the Tajik Defense Ministry insisted fighters from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Chechnya were part of the ambush force, but, as usual, failed to provide any details on these identifications. [17] Despite a lack of evidence that the IMU, which has had little presence outside the northwest frontier region of Pakistan since 2001, was operating in large numbers in the remote Kamarob Gorge, the attack was claimed in a statement purported to have originated with IMU spokesman, Abdufattoh Ahmadi, who said the ambush was in response to a government crackdown on Islam (rather than the more likely struggle between Dushanbe and dissident former commanders who had been excluded from government): “This is our response to Tajikistan’s government, which has lately shut down a thousand mosques, which arrests Muslims without any reason and prohibits women from wearing Muslim clothes. We demand a stop to this policy. Otherwise, terrorist attacks will continue.” [18] The high death toll in the attack was at least partly explained by the poor training and inadequate equipment of the mostly young and inexperienced Tajik troops, leading to calls for the resignation of the Tajik defense minister. [19]

On September 10, 2010 a Tajik border patrol encountered what they described as a large group of Islamist fighters, including Afghan Taliban, trying to cross the border from Afghanistan. A firefight lasting nearly 24 hours ensued, with the border police eventually driving off the alleged Taliban incursion. Authorities claimed one officer and 20 Taliban were killed, though only seven Taliban bodies were recovered. The battle took place roughly 210 kilometers south of Dushanbe on the banks of the Pyandzh River in the remote autonomous Gorno-Badakhshan region and on a number of islands in the river occupied by Taliban fighters. The Taliban appear to have been using the islands as a local base and the clash did not seem to be part of any effort by the Afghan Taliban to mount a campaign within Tajikistan, but was more likely an attempt to evade an ongoing U.S./ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) military operation in the area. The mountainous border along the Pyandzh River was again closed in July 2012 as Tajik authorities claimed Afghan Taliban were infiltrating Tajikistan to support former warlord Tolib Ayombekov, who was accused of murdering Major General Abdullo Nazarov, the regional security service chief. Tajik officials claimed to have captured eight Afghans who were fighting in support of Ayombekov. [20]

Tajik authorities have consistently asserted a leading role for the IMU in Tajikistan’s internal armed opposition, despite strong indications that the 2009-2011 fighting had far more to do with that nation’s tribal rivalries and internal political competition than with a Central Asian jihad. Dushanbe clearly prefers to suggest that its political violence is solely the result of the machinations of international jihadists rather than admit to continuing difficulties in creating a stable state while failing to establish a national purpose or identity that would subsume deep-set political and tribal rivalries.

Rasht Valley, Tajikistan

Rasht Valley, Tajikistan

Before and following his death during a military sweep in the Rasht Valley in April 2011, Mullo Abdullo (a.k.a. Abdullo Rahimov) was described by Tajik authorities as not only an IMU field commander, but the leader of al-Qaeda in Tajikistan, though evidence in support of these claims was never presented. [21] There is little evidence to suggest that Mullo Abdullo had ties of any significance to the IMU and it is common for Tajik courts to identify local militants as IMU members, identifications confirmed by forced confessions. [22] It is informative that most of the major charges brought against former Islamist commanders in recent years relate to crimes allegedly committed in the 1990s rather than current militant activity, a sign that the government’s offensives are directed at eliminating the former Islamist commanders from the Tajik power structure. The international “War on Terrorism” has allowed the Dushanbe regime to follow Karimov’s example in Uzbekistan and frame its struggle with opposition forces as counterterrorism operations against Islamist extremists pursuing a global jihad. This process has also been used in other Central Asian nations, as described by Tajik historian Kamoludin Abdullaev:

On the pretext of fighting Islamic terrorists, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have also rashly strengthened their defense and security bodies. Not capable to resolve problems arising from Islamist mobilization and driven by Soviet-time authoritarian impulses Central Asian governments call for external support receiving millions of dollars from the US to suppress Islamic dissent. Sadly, in the aftermath of September 11, Central Asian governments have begun to apply the rhetoric of the “war on terror” to justify their pressure on opposition. Tajikistan is another source of instability, because the military elite is comprised of former adversaries—hardened militias from pro-Communist Popular Front and United Tajik Opposition—and most gunmen are independent from the state, remaining loyal to regional political entrepreneurs and field commanders who control the remote regions, “protect” the Tajik-Afghan border and are heavily involved in illegal trafficking. [23]

Instability continues on a low scale in the Rasht Valley, in the western part of the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO), the last region of Tajikistan to be brought under the control of the regime of President Imam Ali Rahmon. The GBAO, located in the Pamir Mountains, occupies 45% of the territory of Tajikistan but has only 3% of the total population. The Garm district of the Rasht Valley has a long history as a center for Islamist militancy, dating back to its days as an important center for the anti-Soviet Bashmachi rebellion of the 1920’s. By now, however, most of the leading UTO Islamists are dead, indluding Abdullo, Ziyoev, Ali Bedaki and Mirzokhuja Ahmadov. Nonetheless, analyst Thomas Ruttig has noted a trend to internationalization of Islamist militancy as reported by official sources that is difficult to support with hard evidence:

If one listens to ISAF and to Central Asian governments, there are overlapping networks of jihadist terrorists subverting Afghanistan and Tajikistan, if not the whole region. Those networks, it is said, link the Taleban and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) with al-Qaeda and other Pakistan-based groups. Few of these reports are substantiated by details that can be independently scrutinised. But they are often picked up by media and other outlets, presented as proven facts and amplified by repetition. [24]

Ruttig goes on to point out that much of the activity described as IMU/Taliban penetrations along Tajikistan’s borders is actually related to smuggling rather than jihad. Any IMU effort to insert itself operationally into Tajikistan will be countered by the presence of the Russian 201st Motorized Rifle Division, permanently based in Tajikistan where it has been responsible for guarding the border with Afghanistan against militant incursions since 2001.

In recent years there is greater evidence for the out movement of Tajik extremists taking refuge in Afghanistan than for an inflow of Taliban militants. Nonetheless, Tajik authorities continue to cite an al-Qaeda-assisted IMU revival in Tajikistan in league with Tajik dissidents who would otherwise seem to present only a minimal threat to the Tajik state. Presenting its troubles in the framework of the “war on terrorism” allows the Dushanbe government to avoid discussions of official nepotism, corruption and inefficiency as factors causing unrest in the country.

The European Connection – IMU and IJU

The IMU has attempted to draw on European sources for financial contributions and recruitment, particularly amongst the Turkish diaspora community. In May 2008, Dutch, French and German police announced the break-up of a financial support network run by ethnic-Turks. [25] The IMU has also produced German-language recruitment videos, which have had some limited success. The IMU has successfully recruited a number of German nationals, including Bekkay Harrach, a cell leader born in Morocco and the brothers Mounir and Yasin Chowka.

Another important connection between the Central Asian jihad and Europe was established by the Islamic Jihad Union (IJU). [26] The IJU split from the IMU in 2002, led by two ethnic Uzbeks, Najmiddin Jalolov and Suhail Buranov. While sharing the IMU’s goal of deposing the Karimov regime in Uzbekistan, the movement quickly displayed a more global approach to its jihad, growing close to core al-Qaeda and focusing its activities on attacks against U.S. and ISAF forces in Afghanistan from bases in the north-west frontier region of Afghanistan and recruiting members from the West, especially Germany. Using the name Jama’at al-Jihad al-Islami, the group claimed responsibility for a series of attacks in Uzbekistan in 2004, though the Tashkent government claimed the attacks were the work of Hizb ut-Tahri and the IMU.

The IJU was central to the 2007 “Sauerland Group” plot to use car-bombs against Germany’s Ramstein Air Base (used by U.S. forces) and Frankfurt International Airport. Of the three principal suspects, one was an ethnic Turk raised in Germany and two were German converts to Islam. All three had been trained at IJU camps in South Waziristan. [27] In April 2009, Turkish police arrested members of an IMU cell operating in Turkey. Like the IMU, the IJU now seems to have adapted to a long-term presence in north-western Pakistan but appears to rely on strong support from ethnic-Turkish sources. [28]

Hizb ut-Tahrir and the Tabligh Jama’at

Despite its Palestinian/Jordanian origins and London headquarters, the Central Asian branch of the Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT) movement appears to be a largely localized phenomenon, with affiliates operating with various degrees of success in most of the Central Asian nations. The movement’s international resources are well-deployed in the production of videos and internet communications, but within Central Asia, where technological resources are still in short supply, the movement relies on locally photo-copied leaflets (shabnama – “night letters”) and posters. [29] Though HuT advocates the establishment of a Central Asian caliphate (as the precursor to a global caliphate) and the full implementation of Shari’a through solely peaceful means, it is consistently treated as a militant group by authorities who regard its radical political message as being at least as dangerous as any armed group. Central Asian rulers are mindful of the example of the Askar Akayev regime in Kyrgyzstan, which was overthrown by political protests in the 2005 “Tulip Revolution” rather than by militant groups like the IMU, who have criticized the HuT’s passive approach to political change. [30] The outlawed movement’s cell structure and attention to security makes it particularly difficult to infiltrate, adding another layer of concern for authorities. [31] The harshness with which local authoritarian regimes have dealt with suspected HuT members has in turn helped convince these regimes that the movement will eventually respond with violence. While HuT’s activities do not bear the enormous costs associated with mounting an armed rebellion, the sources of its financing remain obscure, though the existing literature on the movement contains the usual but vague references to Islamic charities and private donors in the Gulf States (which include a substantial Uzbek diaspora population). After dismantling an “HuT network,” Kazakh authorities claimed the operation had “helped dismantle routes that were used to deliver books promoting extremism and money from abroad.” [32] Despite repression, the group has managed to survive, though its activities remain largely limited to the distribution of Islamist and pro-Caliphate literature.

A similar, but less political organization, the Tablighi Jama’at, has also faced repressive measures in Central Asia. The Deobandi-influenced movement was founded in India in 1926 with the aim of bringing about a spiritual revival in the Muslim community through missionary work. The movement has gradually become a well-funded, global mechanism for promoting spiritual reform while avoiding political confrontations with authorities wherever possible. Unlike Hizb ut-Tahrir, the Jama’at considers the establishment of a caliphate as a long-term goal possible only after significant reforms have been achieved in the Islamic community. Despite this, the movement’s call for a return to conservative Islamic principles has alarmed the secular post-Soviet governments of Central Asia. In Tajikistan, the Jama’at was banned in March 2006 after authorities determined the movement aimed to subvert constitutional order in Tajikistan in order to establish an Islamic Caliphate. [33] The movement has made inroads in the Kyrgyz community in the Ferghana Valley and has begun spreading into the Russian Federation republics of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, where they have attracted the attention of Russian authorities. [34]

In 2012, Kazakhstan attempted to disrupt the movement’s activities by expelling or fining 205 Jama’at missionaries on the grounds that religious activities by unregistered organizations were prohibited. [35] The movement is also banned in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, partly because of the theory that the organization acts as a “gateway” to radicalization and eventual militant activity, based on the examples of a number of militants killed or captured worldwide who were former members of the Jama’at, which has at least 100 million members in 213 countries. Despite significant global resources, the movement’s non-political stance makes it difficult to mobilize against government repression. There are no signs at the moment that the Tablighi Jama’at intends to engage in militant activities in Central Asia.

According to Thomas Ruttig:

Statements by Central Asian governments contain high doses of self-serving alarmism, seem to exaggerate and misrepresent relatively small incidents, and describe scenarios that could only become true if different groups significantly increased the intensity, scope and coordination of their activities… Labelling all domestic dissent as ‘Islamist’ or ‘terrorist’ is a long-established pattern. [36]

The ISAF/U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the future of Central Asia’s militants

Uzbekistan’s President Karimov has warned of “an increased threat of the expansion of terrorist and extremist activities” in his nation following the 2014 withdrawal of U.S. and ISAF forces, while Tajik President Rahmon has warned of growing threats from Afghanistan due to Tajikistan’s “weak military situation” and need for modern military equipment. [37] Various Russian sources have similarly predicted that Russian troops in Tajikistan might come under fire from the Afghan Taliban after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014.

Attacks by Islamist militants in Uzbekistan have become rare in recent years, partly as the result of a relentless government campaign against any activity that remotely resembles any form of religious extremism. Security services have cast a wide net in their search for militants and there are numerous reports from human-rights organizations that detention can mean severe treatment and even death. Uzbekistan’s national security service, the Milliy Havfsizlik Hizmati (MHH), has even gone so far as to issue a warning in November 2011 to Uzbekistan’s writers, artists, dramatists and filmmakers to avoid the use of any kind of religious theme in their works.

At this point, the IMU has clearly shifted its focus from Uzbekistan and the other nations of Central Asia to a new role, created through a decade of effective integration, as a largely locally-recruited militia deeply engaged in the tribal politics of the Afghan-FATA frontier region. Despite numerous external claims that the IMU will head back to Central Asia to carry out new, state-threatening operations, the IMU itself has of yet given no indication of such intentions. Since relatively little is known about the discussions taking place within the IMU’s increasingly reclusive leadership, the possibility of an IMU incursion must still be regarded as a possibility, if an unlikely one. The IMU has shown itself incapable of even resisting tribal militias in South Waziristan, which does not hold promise for any IMU effort to vanquish state security forces in Uzbekistan or elsewhere in Central Asia.

A Taliban offensive into Central Asia following the withdrawal of Western forces (or an IMU offensive backed by the Taliban) would not only jeopardize the gains made by the movement in over a decade of bitter fighting, but would also bring it into almost immediate conflict with China and Russia, nations that have prepared for such an eventuality and that do not rely on the long and vulnerable supply lines of U.S. and ISAF forces in Afghanistan.

Predictions of a Taliban overspill into Central Asia from a post-occupation Afghanistan depend greatly upon assumptions that Afghanistan’s Pashtun community harbors a previously unexpressed desire to expand into its northern neighbors or that the Taliban leadership learned nothing from its 2011 experience and is set on repeating behavior that will lead quickly to its annihilation.

The Afghan Taliban have taken little action to disrupt the northern distribution network through extra-territorial strikes, preferring to focus instead on disrupting the Karachi to Khyber Pass supply line in league with their TTP allies. If the Afghan Taliban has been reluctant to strike its Central Asian neighbors when it mattered most, this would seem to argue against Taliban aggression after the 2014 withdrawal. Linguistic, ethnic and cultural differences with the Central Asian communities would also complicate an incursion by the largely Pashtun Taliban.

Conclusion

All of Central Asia’s militant movements share one element in common: their political ambitions exceed their operational capacity. Syria and, to a lesser extent, Iraq, both provide more favorable grounds for financial contributions from jihad supporters in the Gulf States than Central Asia, with the added enticement to Gulf donors of being similarly Arab in nature.

Jihadists are not the only armed groups operating in Central Asia; they may even be smaller in number than trans-national narcotics trafficking groups and smuggling outfits working in the porous and difficult border regions of Central Asia. Many of the reported encounters with “foreign militants” may in reality be clashes with well-armed and highly organized trafficking groups who do not fear small detachments of border guards posted in remote places. The smugglers have at times shown a vicious intent to combat government attempts to interfere with their lucrative activities – in July 2012, suspected tobacco smugglers dragged General Abdullo Nazarov from his car outside the town of Khorog and stabbed him to death, wounding his three bodyguards and driver in the process. General Nazarov was the head of the Tajik State National Security Committee forces in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast and was directing operations against tobacco smugglers at the time. [38] The region is frequently cited by authorities as a center of Islamist militant activities.

Corruption within Central Asia’s anti-narcotics agencies has only contributed to the success of the traffickers and encouraged the identification of gangs of armed gunmen as “foreign militants” rather than local smuggling rings operating with the clandestine cooperation of elements of the regional security forces. In the latest such example, on September 19, 2013, the Kyrgyz general prosecutor’s office announced it was opening a criminal case against members of the Southern Region office of the Chief Administration for Fighting Drug Trafficking for their role in trying to smuggle more than 25 kilograms of drugs to Bishkek disguised as an official shipment. [39] In another example, police in the Kazakh city of Petropavlovsk intending to incinerate more than 100 kilograms of marijuana discovered the drugs had been replaced by bags filled with tobacco and bricks despite being stored in a secured police warehouse. [40]

The IMU’s long absence from its Central Asian homeland has inhibited its ability to recruit locally and diminished the resonance of its message in the Ferghana Valley and elsewhere. [41] The kind of political and/or religious disturbances that might indicate a welcome return to Central Asia from some elements of the population at large have not materialized. Attrition and desertion have weakened the IMU, which now likely numbers only in the hundreds of fighters rather than thousands, with many of these being locally recruited replacements for more experienced IMU veterans. In the event of an IMU reinsertion into Central Asia, many of these fighters would find themselves on unfamiliar geographical and linguistic terrain. Even surviving Uzbeks of the original IMU have experienced a high degree of social integration in their 13 year stay in Afghanistan and north-west Pakistan and might show some reluctance to leave defenseless families and homes behind to engage in somewhat improbable “invasion” of Central Asia, with or without external support.

Notes

1. Uzbek – O’zbekiston Islomiy Harakati; Arabic – Harakat al-Islamiya Uzbekistai

2. Igor Rotar, “Under the Green Banner: Islamic Radicals in Russia and the Former Soviet Union,” Religion, State & Society 30(2), June 2002, pp. 89-153.

3. See Ahmed Rashid, Jihad: The Rise of Militant Islam in Central Asia, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002, pp. 137-40; Bakhtiar Babadzhanov, “Islam in Uzbekistan: From the Struggle for Religious Purity to Political Activism,” Boris Rumer (ed), Central Asia: A Gathering Storm? London: M. E. Sharpe, 2002, pp. 299-330.

4. Kamoludin Abdullaev, “Integrating Political Islam in Central Asia: the Tajik Experience,” November 3, 2010, http://kamolkhon.com/integrating-political-islam-in-central-asia-the-tajik-experience/

5. Michael Feldholm, “From the Ferghana Valley to Waziristan and Beyond: The Role of Uzbek Islamic Extremists in the Civil Wars of Tajikistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Islam, Islamism and Politics in Eurasia Report no. 22, Monterey Terrorism Research and Education Program/Monterey Institute for International Studies, August 25, 2010, http://csis.org/files/publication/100825_Hahn_IIPER_22.pdf

6. Andrew McGregor, “South Waziri Tribesmen Organize Counterinsurgency Lashkar,” Terrorism Monitor, January 14, 2008, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/tm/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=4649&tx_ttnews[backPid]=167&no_cache=1#.Unf3JhAljoY

7. “Punjab banned outfits in contact with Uzbek militants, NA told,” Dawn [Karachi], December 18, 2012, http://dawn.com/news/772230/punjab-banned-outfits-in-contact-with-uzbek-militants-na-told

8. Amir Mir, “TTP using Uzbeks to conduct terrorist attacks,” The News [Islamabad], December 18, 2012, http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-2-149025-TTP-using-Uzbeks-to-conduct-terrorist-attacks; “Uzbek militants behind Peshawar Airport attack,” The Nation [Islamabad], December 17, 2012, http://www.nation.com.pk/pakistan-news-newspaper-daily-english-online/national/17-Dec-2012/uzbek-militants-behind-peshawar-airport-attack; See also Christian Bleuer, “Instability in Tajikistan? The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and the Afghanistan Factor,” OSCE Academy, 2012, http://www.osceacademy.net/upload/file/bleuer_policy_brief7.pdf .

Twelve years of claims by various terrorism “experts” regarding a Chechen military presence in Central Asia, whether as part of IMU, Taliban or al-Qaeda formations, have yet to yield any proof of the existence of these phantom legions of fanatical Chechen extremists. See Brian Glyn Williams, “On the Trail of the ‘Lions of Islam’: Foreign Fighters in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 1980-2010,” Orbis 55(2), 2011, pp. 216-39.

9. See http://furqon.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=195:-1432-2011-&catid=1:2011-08-26-10-42-51.

10. Jacob Zenn, “The Indigenization of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan,” Terrorism Monitor, January 26, 2012, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[swords]=8fd5893941d69d0be3f378576261ae3e&tx_ttnews[any_of_the_words]=uzbekistan&tx_ttnews[pointer]=11&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=38931&tx_ttnews[backPid]=7&cHash=abba18744b7d716ca4d2c38bcecd7340#.UmaT5hAliRN

11. Michael Taarnby, Islamist Radicalization in Tajikistan: An Assessment of Current Trends, Korshinos Center for Socio-Political Studies/OSCE Tajikistan, Dushanbe, 2012.

12. Igor Rotar, “Will Tajikistan’s Karategin Valley Again Become a Militant Stronghold?” Eurasia Daily Monitor, September 13, 2012, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/edm/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=39842&tx_ttnews[backPid]=587&no_cache=1#.Unf2axAljoY \

13. RFE/RL Uzbek Service, July 16, 2009; Ferghana.ru, July 16, 2009.

14. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, “IMU Leader Says Group Did Not Kill Former Tajik Minister,” July 16, 2009, http://www.rferl.org/content/IMU_Leader_Says_Group_Did_Not_Kill_Former_Tajik_Minister/1778214.html ; see also Millat [Dushanbe], July 23; al-Jazeera, July 16, 2009; IWPR, July 23, 2009.

15. See Interfax, August 5, 2009; Asia Plus [Dushanbe], July 29, 2009.

16. See Asia-Plus [Dushanbe], July 28, 2009.

17. See RIA Novosti, September 20, 2010; Itar-Tass, September 26, 2010.

18. Roman Kozhevnikov, “Al-Qaeda ally claims Tajik attack, threatens more,” Reuters, September 23, 2010, http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/09/23/us-tajikistan-security-idUSTRE68M28M20100923; See also Radio Liberty Tajik Service, September 23, 2010; Ferghana.ru, September 24, 2010.

19. See Farazh [Dushanbe], September 22, 2010; Chark-i Gardun [Dushanbe], September 22, 2010.

20. Moign Khawaja, “Tajik security forces clash with Taliban along border,” Foreign Policy Journal, September 13, 2010, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/09/13/tajik-security-forces-clash-with-taliban-along-border/; Reuters, “Tajikistan seals Afghan border, NATO trucks can pass,” July 27, 2012, http://tribune.com.pk/story/413786/tajikistan-seals-afghan-border-nato-trucks-can-pass/

21. Lola Olimova, “Few tears shed for ‘Tajik Bin Laden’,” IWPR, May 5, 2011, http://iwpr.net/report-news/few-tears-shed-tajik-bin-laden

22. Alexander Sodiqov and Payam Foroughi, “Tajik Security Agencies Face Allegations of Detainee Abuse and Extrajudicial Killings,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, December 7, 2011, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/edm/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=38753&tx_ttnews[backPid]=512&no_cache=1#.Unf2JRAljoY

23. Kamoludin Abdullaev, “Integrating Political Islam in Central Asia: the Tajik Experience,” November 3, 2010, http://kamolkhon.com/integrating-political-islam-in-central-asia-the-tajik-experience/

24. Thomas Ruttig, “Talebs in Tajikistan? The ‘terrorist spill-over’ hype,” Afghan Analysts Network, October 10, 2013, http://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/talebs-in-tajikistan-the-terrorist-spill-over-hype

25. Einar Wigen, Islamic Jihad Union: Al-Qaeda’s Key to the Turkic World? Norwegian Defence Research Establishment, 2009.

26. Uzbek – Islomiy Jihod Ittihodi; Arabic – Itiha’ad al-Jihad al-Islami.

27. “Terroralarm in Deutschland: Die Bombenbauer aus der Provinz,” Spiegel Online, September 7, 2009, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/terroralarm-in-deutschland-die-bombenbauer-aus-der-provinz-a-504464-3.html

28. Guido Steinberg, “A Turkish al-Qaeda: The Islamic Jihad Union and the Internationalization of Uzbek Jihadism,” Strategic Insights, Center for Contemporary Conflict. December 30, 2007, http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/fachpublikationen/sbg_IJU_Strategic_Insights_ks.pdf

29. Ehsan Ahrari, “Countering the Ideological Support for HT and the IMU: The Case of the Ferghana Valley,” CSRC discussion paper 05/44, September 2005, p.5, http://www.marshallcenter.org/mcpublicweb/de/component/content/article/628-art-pubs-occ-papers-03.html?directory=19

30. “Tahir Yuldash, ‘US fiasco is nearing. Look us up in Washington’” Ferghana.Ru News Agency, October 15, 2007, http://enews.fergananews.com/article.php?id=2167

31. Dilafruz Nabiyeva, “Hizb ut-Tahrir grows more active in Tajikistan: Government takes anti-terrorist measures,” Central Asia Online, September 6, 2011, http://centralasiaonline.com/en_GB/articles/caii/features/main/2011/07/06/feature-01; “Tajikistan detains influential member of Hizb ut-Tahrir,” Interfax [Dushanbe], June 15, 2011, http://www.interfax-religion.com/?act=news&div=8517

32. “Hizb ut-Tahrir network dismantled in Kazakhstan,” Interfax-Religion.com, December 22, 2006, http://www.interfax-religion.com/?act=news&div=2412

33. See Central Asia Online, July 21, 2009; Interfax, August 11, 2009.

34. Igor Rotar, “Tablighi Jamaat: Islamization from Ferghana Valley to Russian regions?” Eurasia Daily Monitor, January 23, 2013, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/edm/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=40356&tx_ttnews[backPid]=685&no_cache=1#.Unf15xAljoY

35. Ibid

36. Thomas Ruttig, “Talebs in Tajikistan? Part 2 on the alleged IMU-Taleban nexus,” October 11, 2013, http://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/talebs-in-tajikistan-part-2-on-the-alleged-imu-taleban-nexus

37. See Trend.az [Tashkent], January 14, 2013; “President of Tajikistan informs about increasing threats from Afghanistan at CSTO summit,” AKI Press [Bishkek], September 24, 2013, http://www.akipress.com/_en_news.php?id=137484.

38. “Tajik GKNB general killed by smugglers,” Central Asia Online, July 23, 2012, http://centralasiaonline.com/en_GB/articles/caii/newsbriefs/2012/07/23/newsbrief-03

39. “Kyrgyz accuse suspected drug smugglers,” Central Asia Online/RIA Novosti, September 20, 2013, http://centralasiaonline.com/en_GB/articles/caii/newsbriefs/2013/09/20/newsbrief-01

40. “Kazakh police warehouse loses more than 100kg marijuana,” Tengri News [Astana], April 15, 2011.

41. Maksim Yeniseyev, “IMU lacks popular support: Uzbeks urge terrorist group members to lay down arms,” Central Asia Online, July 15, 2011, http://centralasiaonline.com/en_GB/articles/caii/features/main/2011/07/15/feature-01

Chisiru, a 17-year-old male elephant, is trained to detect explosives

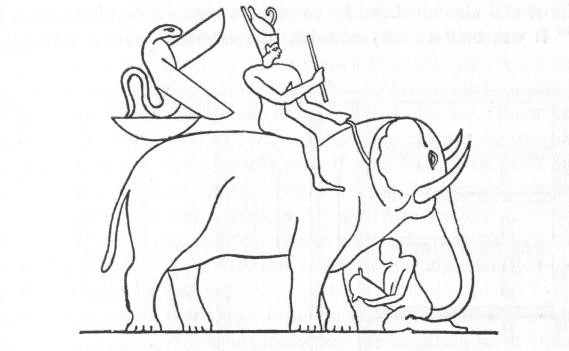

Chisiru, a 17-year-old male elephant, is trained to detect explosives A 3rd century representation of a Meroitic king riding an elephant. From the Lion Temple at Musawwarat, Upper Nubia

A 3rd century representation of a Meroitic king riding an elephant. From the Lion Temple at Musawwarat, Upper Nubia