Andrew McGregor

April 30, 2007

The creation of a largely autonomous and peaceful “Kurdistan” in northern Iraq is often trumpeted as a major success in post-Baathist Iraq. Any progress made, however, toward an independent nation for the stateless Kurds creates great uneasiness in Turkey, Syria and Iran, all of which host significant and sometimes militant Kurdish minorities. Turkey’s struggle with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in southeast Turkey has cost 35,000 lives since 1984.

The Turkish government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is determined to pre-empt a spring offensive by the PKK. If the Iraqi government and U.S.-led forces are unwilling to cooperate with each other to counter the PKK, a designated terrorist organization, Turkey has signaled that it is willing to operate unilaterally. Last August, following a number of clashes with PKK guerrillas, Turkey massed tanks, artillery and troops along the Iraqi border. The PKK consistently denies that operations are launched from the Mount Qandil area in northern Iraq, claiming that it maintains only a “political presence” there. Last weekend, however, the Turkish army took its first steps in mounting a full-scale offensive against the Iraqi bases of the PKK. Mine-clearing operations are underway along the border, while Turkish Special Forces have reportedly penetrated 20 to 40 kilometers inside northern Iraq to prepare the advance and seal off PKK escape routes. As many as 200,000 Turkish soldiers are being brought up to the border this week.

With Turkish presidential and general elections approaching, Turkish security forces have carried out mass arrests of alleged PKK terrorists in Istanbul and have detained 19 members of the Kurdish Democratic Society Party in Izmir and Manisa (The New Anatolian, March 21). Turkey has been busy resupplying army divisions along the Iraq border and has cancelled all leave for these formations for the next three months (Zaman, March 20).

The PKK’s Iraqi Harbor

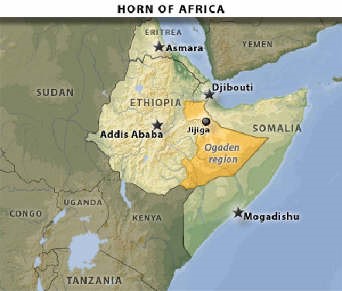

The PKK arrived in northern Iraq after Syria ended its sponsorship of the movement in 1998. The movement’s long-time leader, Abdullah Ocalan, was arrested in Kenya shortly afterward and brought to trial in Turkey. The PKK still contains a large number of Syrian Kurds, some of whom are now agitating for attacks on Syria. In Iraq, the PKK established bases around Mount Qandil, close to the Iranian border but about 100 kilometers from the border with Turkey. The PKK has bases on the west side of the mountain while its Iranian equivalent, the Party for a Free Life in Kurdistan (PJAK), has a base on the southern slopes close to the Iranian border. While the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) of Massoud Barzani has provided some support to the PKK, both Barzani and Iraqi President Jalal al-Talabani (leader of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan) have little use for the imprisoned PKK leader. During past Turkish incursions against PKK elements in Iraq, fighters from both the Barzani and al-Talabani factions have been known to operate in support of Turkish troops.

Turkish intelligence estimates that there are 3,800 Kurdish fighters in the Qandil region ready to carry out attacks on Turkish military and civilian targets. PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan is believed to still be trying to run the movement through messages passed through his lawyers from his cell on the prison island of Imrali. Recent medical tests failed to find any trace of toxins after rumors spread that Ocalan was being poisoned in captivity (Anatolia News Agency, March 12). Ocalan’s attempts to control the movement from a distance have stifled the emergence of a new political leadership. Without strong central leadership, the PKK is subject to fragmentation due to the disparate origins and motivations of its fighters.

Despite their apparent weakness, the PKK has threatened to expand the conflict to neighboring countries if they continue to interfere with the movement’s struggle against Turkey. KRG leader Massoud Barzani has also threatened to deploy Kurdish troops against Turkish forces should they cross into Iraq. Kurdish intentions to absorb the Iraqi city of Kirkuk with its immense oil reserves and large Turkmen population into a northern Iraqi “Kurdistan” is another growing irritant in Turkey’s relations with the Iraqi Kurds. There are fears that Kirkuk’s petroleum industry could provide the economic heart of a viable and independent Kurdistan that would inspire Kurdish separatism in neighboring states.

NATO Allies at Odds

Turkish dissatisfaction with U.S. efforts to root out the PKK comes at a difficult time. The current U.S. Congress debate on the WWI-era “genocide” of Armenians by the Ottoman Empire is quickly poisoning U.S.-Turkish relations, particularly in the politically powerful Turkish armed forces. To mollify Turkish opinion, the United States has appointed a special envoy to deal with the PKK issue, retired Air Force General Joseph Ralston. General Ralston has stated that “the PKK is a terrorist organization and needs to be put out of business” (Zaman, March 16). Besides Turkey’s status as a vital cornerstone of the NATO alliance, southern Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base is also a crucial staging ground for U.S. operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The United States is unwilling to open a new front in northern Iraq, nor can it afford to lose its support from Iraq’s Kurdish population. Kurds provide the most reliable units in the reformed Iraqi national army and have taken part in recent counter-terrorism operations in Baghdad and other parts of the country dominated by Sunni or Shiite political factions.

Turkish Cooperation with Iran?

In late February, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards pursued PJAK elements through the Iranian province of West Azerbaijan to the Turkish border, killing 17 guerrillas (IRNA, February 24). It was only the latest in a series of intense clashes between the Revolutionary Guards and PJAK in the northwestern region of Iran. Iranian artillery frequently fires on the PJAK base at Mount Qandil. PJAK is generally regarded as the Iranian wing of the PKK, with which it cooperates. There are seven million Kurds in Iran, who are actively seeking greater economic and commercial ties with Turkey.

(Economist)

Turkey and Iran have quietly worked out a reciprocal security arrangement, whereby Iran’s military will engage Kurdish separatists whenever encountered, in exchange for Turkey’s cooperation against the Iranian Mujahideen-e-Khalq movement (MEK), a well-armed and cult-like opposition group that previously found refuge in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Both Iranian officials and Turkey’s prime minister have alluded to “mechanisms” (likely to involve intelligence-sharing) already in place to deal with security issues of mutual interest. Neither Turkey nor Iran has any desire to see an independent Kurdish state established in northern Iraq. For the moment, Turkey’s cooperation with Iran is achieving better results than its frustrating inability to persuade the United States to help eliminate a designated terrorist group in northern Iraq. The Erdogan government continues to forge a distinctly Turkish foreign policy, conducted in alliance with, but not in submission to, the United States. In a recent interview, Erdogan vowed that Turkey would not allow attacks on its neighbors from its territory, adding, in an obvious allusion to Iran, that all countries had a right to pursue the development of a peaceful nuclear energy program (Milliyet, March 12).

Iran complains that the British and U.S. intelligence agencies are now supporting and inciting “anti-revolutionary” militant groups, some of which are ethnic-based movements active in sensitive border regions. Nearly all of these groups use terrorist methods, such as car bombs, one of which recently killed 17 Revolutionary Guards members traveling in a bus near the Iranian border with Pakistan’s turbulent Balochistan province.

In January, Turkish diplomats played down reports that Israel and the U.S. Department of Defense were providing clandestine support to Kurdish PJAK “terrorists,” operating in the northwestern Iranian border region, questioning the usefulness of such a policy in countering Iran’s nuclear ambitions or destabilizing the country in advance of a military strike (Journal of Turkish Weekly, January 4). The reports, originating in a Seymour Hersh article in the January 4 New Yorker, were vigorously denied by White House and Israeli spokespersons. Since then, there have been further allegations that the CIA is using its classified budget to support terrorist operations by disaffected members of Iran’s ethnic minorities, including Azeris, Baloch, Kurds and Arabs (Sunday Telegraph, February 25).

Potential Outcomes

Turkey supports the territorial integrity of Iraq, but is unwilling to sacrifice its own perceived security interests (especially as regards separatist groups or other threats to national unity). In this, the government has the support of Turkey’s generals and most of the opposition parties. The Turkish military is well aware that the elimination of cross-border refugees and support systems is an essential factor in any counter-insurgency strategy. Whether this will be accomplished peacefully or by force will depend largely on the success of the upcoming meeting of U.S. and regional foreign ministers in Istanbul. Among those elements necessary to a political settlement are Turkey’s readiness to make at least limited concessions to its own Kurdish community, a demonstration from the United States that it is not prepared to risk its alliance with a major NATO partner during the growing confrontation with Iran and a willingness by Iraqi Kurds to sacrifice the PKK and dreams of an independent “Greater Kurdistan” in return for regional autonomy in northern Iraq.

Iran may be expected to continue aggressive military operations against Kurdish militants to keep its border region secure in a politically volatile period, while continuing to demonstrate to Turkey its usefulness as a security partner in contrast to U.S. reluctance to undertake anti-Kurdish military activities. U.S. intervention in northern Iraq’s Kurdistan region could create a new wave of destabilization in Iraq, as well as diverting U.S. resources from a confrontation with Iran (a result no doubt desired by Tehran).

A Turkish incursion will likely have limited scope and objectives, although it will likely include at least two divisions (20,000 men each) with support units. The last major cross-border operation 10 years ago involved 40,000 Turkish troops. With the greater distance to PKK bases at Mount Qandil from the Turkish border, a first wave of helicopter-borne assault troops might follow strikes by the Turkish Air Force. An assault on Mount Qandil will prove difficult even without opposition from Iraqi Kurdish forces. More ambitious plans are likely to have been drawn up by Turkish staff planners for a major multi-division offensive as far south as Kirkuk if such an operation is deemed necessary. A Turkish newspaper has reported that General Ralston has already negotiated a deal with the KRG to permit a Turkish attack on Mount Qandil in April (Zaman, March 25).

Conclusion

While tensions peak on the border, the time has in many ways never been better for a resolution to the Turkish-Kurdish conflict. From captivity, Abdullah Ocalan appears ready to concede Turkey’s territorial unity in exchange for stronger local governments. He recently stated, “The problems of Turkey’s Kurds can only be solved under a unitary structure. This is why Turkey’s Kurds should look to Ankara and nowhere else for a solution” (Zaman, March 26). Turkish investment in northern Iraq is far preferable to having Turkish tanks and artillery massed menacingly along the border. If the KRG was intending to keep the PKK as a card to use in coercing Turkish support for Kurdish autonomy, it may be time to play it. PKK morale is low and prolonged inactivity under the aging leadership will ultimately send many fighters back to their villages. The movement is hardly in a position to mount an effective offensive, however. Without state sponsorship, the PKK is poorly armed and supplied. The KRG’s limited hospitality is hardly a replacement for Syrian patronage. Massoud Barzani has urged face-to-face talks on the PKK problem with Turkish leaders, who have also recently indicated openness to discussion (NTV, February 26). Turkey’s continuing conflict with the Kurds jeopardizes its candidacy for European Union membership. With the possibility of full-scale Turkish military operations beginning in northern Iraq in the coming weeks, both U.S. and Turkish strategists must realize that any clash between the Turkish military and U.S.-supported Iraqi Kurds backing their PKK brethren is a political disaster in waiting.

This article first appeared in the April 30, 2007 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor