Andrew McGregor

January 25, 2013

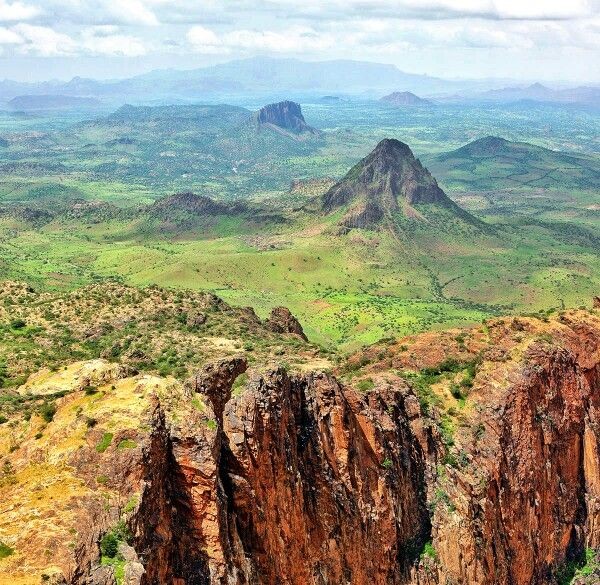

One of the reported demands of the terrorist group that seized the In Aménas gas field last week was safe passage to the Libyan border, some 30 miles away and the likely launching point for their attack on Algeria. This should not be surprising, despite a stream of statements from Benghazi regarding increased security in southern Libya, an oil-rich region that has also become a home for criminal gangs, arms traders, smugglers, militias, armed tribal groups and foreign gunmen since the fall of the Qaddafi regime.

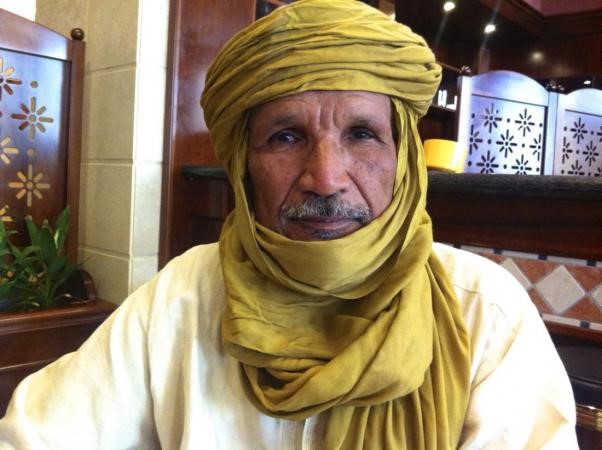

Tubu Border Guards (Rebecca Murray/IPS)

Tubu Border Guards (Rebecca Murray/IPS)

The alleged planner of the In Aménas attack, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, is believed to have traveled to southwestern Libya in the fall of 2011, possibly returning there in the spring of 2012. In November 2011, Belmokhtar told a Mauritanian news agency that he had purchased Libyan weapons to arm his group (Nouakchott Info, November 11, 2011; CNN, January 21, 2012). He was again reported to be in southwestern Libya by Malian security sources in March 2012 (AFP, March 12, 2012). Both occasions would have allowed Belmokhtar to establish important connections with local Islamists or others willing to work for him. Belmokhtar could also have used these trips to reconnoiter routes from northern Mali through Niger into southwestern Libya, possibly by crossing the lifeless Tafassâsset desert.

At least two of the terrorists involved in the attack on Algeria’s In Amenas natural gas facility have been identified as Libyan by the Algiers government (Libya Herald, January 17). Amidst fears that Libya might have provided the staging ground for the terrorist raid on In Aménas, Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zidan promised that “Libya will not allow anyone to threaten the safety and security of its neighbors” (Reuters, January 19). Zidan’s government has rejected the “attacks on Mali,” urging a return to dialogue to resolve the situation there (Tripoli Post, January 21). Prime Minister Zidan has been reluctant to acknowledge terrorist activity within southern Libya, but claims that “There are powers that don’t want stability involved in white slavery, drugs smuggling, arms smuggling, money laundering and others who want North Africa to be a theatre of instability” (Libya Herald, January 19).

Protecting Libya’s Oil Infrastructure

Libya has recently created the Petroleum Faculty Guard (PFG), a force dedicated to protecting energy operations in the vast Libyan interior. In the aftermath of the In Aménas attack, the PFG announced it was taking steps to secure Libyan energy facilities, including “the formation of a special operations room, adding military air support and increasing guards and military personnel, and intensifying security patrols inside and outside the sites around the clock to block any attempt from anyone who wishes to compromise public property” (Libya Herald, January 18). As seen in Algeria, however, deploying troops as guards is not enough; they must be well-commanded, maintain an appropriate system of patrols and level of vigilance and be supplied with the necessary intelligence to do their job.

Efforts are under way to try and integrate many of the militias active in southern and western Libya into the newly-formed National Guard, which operates directly under the Libyan head-of-state but may soon be transferred to the control of the Interior Ministry. For the moment, many members of the 10,000 man force are working in support of the Libyan Border Guards (Libyan Herald, January 8).

Last December, EU foreign ministers met to consider the problems created by the trafficking through Libya of arms and illegal migrants (many of them bound for Europe). Italy emphasized the need for stronger border controls and urged its counterparts to initiate a border guard training mission by January, a proposal considered “unrealistic” by other EU diplomats, who suggested training could wait to begin in mid-2013 (Reuters, December 10, 2012).

Prime Minister Ali Zidan rejected rumors that the southern al-Wigh airbase was being used as a base for French operations in Mali or as a base for terrorist operations in Algeria (Reuters, January 19; al-Wataniyah TV, January 19; Tripoli Post, January 21). Al-Wigh was an important strategic base for the Qaddafi regime, being located close to the borders with Niger, Chad and Algeria. Since the rebellion, the base has come under the control of Tubu tribal fighters under the nominal command of the Libyan Army and the direct command of Tubu commander Sharafeddine Barka Azaiy, who complains: “During the revolution, controlling this base was of key strategic importance. We liberated it. Now we feel neglected. We do not have sufficient equipment, cars and weapons to protect the border. Even though we are part of national army, we receive no salary” (Libya Herald, December 23, 2012). Since the hostage-taking in neighboring Algeria, Prime Minister Zidan has ordered surveillance operations and patrols to be stepped-up in the region of al-Wigh (al-Wataniya TV, January 19).

Only days before the raid on In Aménas, the premiers of Libya, Algeria and Tunisia met on January 12 at the Libyan oasis border town of Ghadames to discuss border security, with an eye to securing their borders “by fighting against the flow of arms and ammunition and other trafficking” (AFP, January 10). There are continuing tensions in the region around Ghadames near Libya’s border with Tunisia and Algeria, where Arab-Berber tribes have sought revenge on the local Tuareg community, parts of which provided security support to the Qaddafi regime during the battle for Libya.

On December 15, Libya’s ruling General National Congress (GNC) declared that Libya’s borders with Algeria, Chad, Niger and Sudan would be temporarily closed and designated the regions of Ghadames, Awbari, Sabha, al-Shati, Murzuq and Kufra as military zones to be ruled by a military governor. Only certain roads in the south would remain open, with Prime Minister Zidan warning that caravans, convoys or other groups using anything other than official frontier posts would face action by land forces or military aircraft (Libyan News Agency, December 16, 2012; Libya Herald, December 18, 2012). Two days later, Libyan fighter-jets struck a suspected smugglers’ camp in the Kufra region near the borders with Chad and Sudan. During the anti-Qaddafi rebellion, Sudanese troops coordinating with Qatari forces moved into the strategically important Kufra region and helped rebel forces seize the oasis (Sudan Tribune, August 28, 2011; Telegraph, July 1, 2011). According to air force spokesman Colonel Miftah al-Abdali, Libyan warplanes would monitor the Kufra region from the border with Chad to Jabal al-Uwaynat and Jabal al-Malik near the border with Egypt (Libyan News Agency, December 19). Eventually Libya plans to establish only one authorized border crossing with each of its four southern neighbors, Chad, Niger, Sudan and Algeria (AFP, December 19).

The new military governor for the south has the authority to detain and deport illegal immigrants, initiating a round-up of refugees and migrants in parts of southern Libya. These powers were seen as necessary in expectation of a greater flow of “illegal immigrants” from an expected war in northern Mali. Libya is concerned that if things go poorly for the Islamists in Mali, there will be a reverse flow of fighters and weapons back into southern Libya in the hands of armed groups.

Tunisia – A Conduit for Libyan Weapons?

On January 12, Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki suggested that local jihadists had ties with terrorist forces in northern Mali and that Tunisia was “becoming a corridor for Libyan weapons to these regions” (AFP, January 12). The Tunisian border with Libya is rife with the smuggling of everything from milk to explosives since the collapse of the Qaddafi regime. Violent incidents have become common – two uniformed Libyans were arrested on the night of January 17 after using a 4X4 vehicle to attack the Tunisian security post at Jedelouine (Libya Herald, January 18; For the smuggling routes across the Tunisian-Libyan border, see Terrorism Monitor Brief, May 20, 2011).

While the hostage crisis was still ongoing in Algeria, Tunisian security forces announced the discovery of two large arms depots in the southeastern town of Medenine on the main route to Libya. The materiel seized at the depots included bombs, missiles, grenades, rocket launchers, ammunition, bullet-proof vests, uniforms and communications equipment (Tunis Afrique Press, January 18).

The Egyptian Border and the Route to Gaza

A minor crisis in Libyan-Egyptian relations occurred on January 18 when a Lebanese newspaper, al-Diyar, reported that Egyptian prime minister Hisham Qandil claimed Egypt had rights over parts of eastern Libya. Though historical claims to parts of the Libyan Desert once existed, they were renounced by Egypt in a 1925 agreement with Italy, the occupying power of the time. After Libyan premier Ali Zidan appealed for clarification, the Egyptian government issued a firm denial: “These alleged statements were not made by Qandil or any Egyptian official” (Egypt State Information Service, January 21).

Libya and Egypt fought a three-day border war in July, 1977 after Qaddafi sent thousands of protesters on a “March to Cairo” to protest Egypt’s progress towards a peace treaty with Israel. When the demonstrators were turned back at the border, Libyan forces raided the coastal town of Sollum, the site of fighting between Sanusi militants and the British-controlled Egyptian Army during the First World War. Retaliation came swiftly in the form of three Egyptian divisions supported by fighter-jets destroying Libyan opposition as they crossed the border into Libya. A complete invasion was averted only by the mediation of Algerian president Houari Boumediène.

More recently, it appears that a shipment route for Libyan arms on their way to Sinai and Gaza has been opened along the northern coast of Egypt, encouraging greater activity by militants in the area. There are fears in Cairo that these militants could eventually turn the Libyan weapons against the Egyptian government (see Terrorism Monitor, May 18, 2012). [1]

Sabha Oasis – A Strategic Base under Threat

GNC President Muhammad Magarief toured southern Libya earlier this month, meeting with Major General Omran Abd al-Rahman al-Tawil and other military officials in the strategic southern oasis of Sabha. While in Sabha, Magarief’s hotel was attacked by gunmen who wounded three of his guards (Libya Herald, January 6; al-Jazeera, January 13).

Six days of clashes between the Qadhadhfa (the Arab-Berber tribe of Mu’ammar Qaddafi) and the Awlad Sulayman tribe left four dead and several others wounded in Sabha on January 2 (AFP, January 2). An attempt by Libyan Special Forces units to enter the town on December 31 and impose a truce ultimately failed when fighting resumed (Libya Herald, January 4). The oasis town, 500 miles south of Tripoli, was the site of an important air-base during the Qaddafi regime and many of the current tribal clashes are rooted in differences between the Qadhadhfa, regarded as Qaddafi supporters, and the Awlad Sulayman, who opposed Qaddafi in the rebellion (see Terrorism Monitor, April 5, 2012).

The inability of security forces in Sabha to keep detainees under lock and key has contributed to the insecurity in the region. On December 4 there was a mass breakout of 197 inmates from the Sabha jail with the apparent assistance of the Judiciary Police responsible for guarding them (Libya Herald, December 6, 2012). Local authorities claimed most of the prisoners were common criminals, while others were alleged to be Qaddafi loyalists (Reuters, December 5). In July 2012, 34 prisoners escaped another detention facility in Sabha by crawling through ventilation shafts. The most recent breakout was followed by 20 southern GNC representatives walk out of the Libyan Congress to protest the “deteriorating security situation in their region,” saying the government’s inability or unwillingness to address these problems was “the last straw” (AFP, December 16, 2012; Libya Herald, December 6, 2012; December 18, 2012).

There are plans to spur development in Sabha by turning its military airport into a regional air cargo hub, but this is unlikely to happen so long as the region remains plagued by violence and instability.

Kufra Oasis – Where Race Politics Meets Border Security

Clashes between the Black African Tubu and the Arab Zawiya tribe continue in the southeastern Kufra Oasis, where inter-tribal fighting earlier this month developed into firefights between the Tubu and members of the Libyan Desert Shield, a pro-government militia that was flown into Kufra last year to bring the region under control. Desert Shield has failed to win the trust of the Tubu, who accuse the militia’s northern Arabs of siding with the Zawiya. According to a Tubu tribal chief in Kufra: “We want the army to secure Kufra, and not a group of civilian revolutionaries who have no military principles” (AFP, January 9; For the struggle over Kufra, see Terrorism Monitor Brief, May 5, 2011, Terrorism Monitor, February 23, 2012).

Tubu fighters in the Kufra region are led by Isa Abd al-Majid Mansur, head of the Tubu Front for the Salvation of Libya (TFSL), founded in 2007 to combat the Qaddafi regime on behalf of the disenfranchised Tubu community. Following a failed revolt against Qaddafi and his “Arabization” program, the Tubu had their citizenship stripped, access to services cancelled and their homes bulldozed. Prior to the declaration of a military zone in the south, Mansur maintained that Libya’s southern borders from Sabha to Kufra were controlled and guarded by desert-savvy Tubu tribesmen after the fall of Qaddafi (Libyan Herald, December 23, 2012; January 13, 2013). Local Arab tribes accuse the Tubu of actually seizing control of the region’s smuggling routes for their own profit.

Government authorities maintain there are only some 15,000 Tubu tribesmen in Libya, while Tubu activists claim the real number is closer to 200,000. According to Tubu activist Ahamat Molikini, the Tubu are confronting an Arab desire to create a new demographic reality in the south: “Many from the [Arab] Zuwaya and Awlad Sulayman tribes want the Tubu people out before they create a new Libya, before it becomes a democracy. They provoke the Tubu with these new attacks and killings, they create conflict to evict them.” These tribes have succeeded in convincing the northern Arab tribes that the native Tubu who predate the Arab presence in southern Libya are actually foreigners (a popular Qaddafi canard) “with an agenda to make southern Libya an independent country” (Minority Voices Newsroom, January 8).

No Better in Benghazi

In the de facto Libyan capital of Benghazi, meanwhile, a campaign of attacks on members of the police and military continues as Western nations begin to pull out their nationals amidst rumors of an impending terrorist attack. Many of the victims of assassination were formerly employed by the Qaddafi regime (Xinhua, January 14; January 16; see Terrorism Monitor Brief, August 10, 2012). The government is considering what it described as a “partial curfew” to help deal with the deterioration of security in Benghazi (Middle East Online, January 17).

Western diplomats also continue to be targeted; on January 12, unidentified gunmen fired on the Italian consul’s bullet-proof car, damaging the vehicle but causing no casualties in a strike that Italian Foreign Minister Giulio Terzi described as “a vile act of terrorism” (AFP, January 13; Xinhua, January 12). On January 16, Italy agreed to provide logistical support to air operations targeting terrorists in northern Mali after shutting down its Benghazi consulate and withdrawing all diplomatic personnel (Telegraph, January 16; UPI, January 16; Reuters, January 16).

On January 19, a car carrying Libya’s defense minister, Muhammad al-Barghati, came under attack at the Tobruk airport, east of Benghazi. Al-Barghati claimed the attack was the work of followers of al-Sadiq al-Ghaithi al-Obeidi, a reputed jihadist who had just been sacked as deputy defense minister after refusing to bring his fighters under the command of the army’s chief-of-staff. Al-Obeidi was formerly responsible for border security and the security of foreign oil installations (AFP, January 19; Reuters, January 21).

Conclusion

The “closed military zones” of the south are little more than a fiction without the resources, personnel and organization necessary to implement strict controls over a vast and largely uninhabited wilderness that is nonetheless the heart of the modern Libyan state due to its vast reserves of oil and gas that provide the bulk of national revenues and its aquifers of groundwater that permit intensive agriculture and supply drinking water for Libya’s cities.

The Libyan GNC and its predecessor, the Transitional National Council (TNC), have failed to secure important military facilities in the south and have allowed border security in large parts of the south to effectively become “privatized” in the hands of tribal groups who are also well-known for their traditional smuggling pursuits. In turn, this has jeopardized the security of Libya’s oil infrastructure and the security of its neighbors. As the sale and transport of Libyan arms becomes a mini-industry in the post-Qaddafi era, Libya’s neighbors will eventually impose their own controls over their borders with Libya so far as their resources allow. Unfortunately, the vast amounts of cash available to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb are capable of opening many doors in an impoverished and underdeveloped region. If the French-led offensive in northern Mali succeeds in displacing the Islamist militants, there seems to be little at the moment to prevent such groups from establishing new bases in the poorly-controlled desert wilderness of southern Libya. So long as there is an absence of central control of security structures in Libya, that nation’s interior will continue to present a security threat to the rest of the nations in the region, most of which face their own daunting challenges in terms of securing long and poorly defined borders created in European boardrooms with little notice of geographical realities.

Note

1. See Andrew McGregor, “The Face of Egypt’s Next Revolution: The Madinat Nasr Cell,” Jamestown Foundation “Hot Issue,” November 20, 2012, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/gta/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=40137&cHash=bc3b95312dc7c4911c1727f4b929e2fd

This article first appeared in the January 25, 2013 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.