Andrew McGregor

April 6, 2018

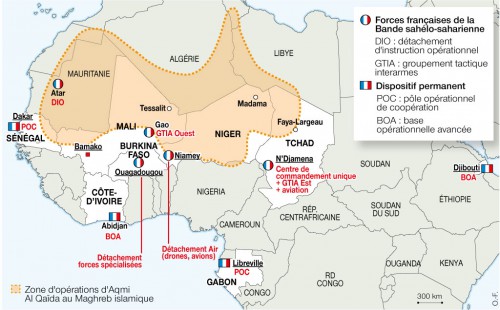

Renewed fighting in southern Libya around the Kufra and Sabha oases demonstrates the difficulty of reaching anything more substantial than temporary and fragile political agreements in the region. The parties to the seemingly intractable conflict in the south include a range of legitimate and semi-legitimate actors – forces allied to Libya’s rival governments, self-appointed police and border security services – and illegitimate actors, such as foreign mercenaries, bandits, jihadists and traffickers.

Renewed fighting in southern Libya around the Kufra and Sabha oases demonstrates the difficulty of reaching anything more substantial than temporary and fragile political agreements in the region. The parties to the seemingly intractable conflict in the south include a range of legitimate and semi-legitimate actors – forces allied to Libya’s rival governments, self-appointed police and border security services – and illegitimate actors, such as foreign mercenaries, bandits, jihadists and traffickers.

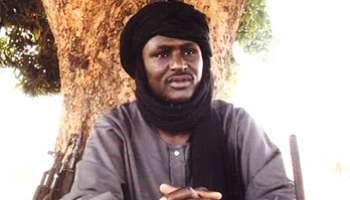

Tubu Tribesmen in Sabha, southern Libya (Libyan Express)

Tubu Tribesmen in Sabha, southern Libya (Libyan Express)

The fact that membership of these groups often overlaps leads to heated clashes over turf and privileges that endanger the civilian population while inhibiting sorely-needed development initiatives. On March 13, the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) warned that the build-up of armed forces in the south “risks further escalation” of the ongoing violence. [1] Tensions are so high at present that even the body of the 19th century head of the Sanusi order has been pulled into the struggle for the resource-rich deserts of southern Libya.

The Madkhali Infiltration

The Saudi-backed Madkhalist religious sect is the most prominent player in the Kufra and Sabha violence. A basic tenet of Madkhalism is respect for legitimate authority, the wali-al-amr. This Salafist movement was first introduced to Libya by Mu’ammar Qaddafi to counter Libya’s more revolutionary Salafist groups. Madkhalist militias in Libya typically seek to control local policing duties, providing them a degree of immunity while enforcing Salafist interpretations of Shari’a that have little in common with traditional Libyan Islamic practice.

Although Saudi sect leader Rabi bin Hadi al-Madkhali issued a surprising declaration of support in 2016 for General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) in its fight against “the Muslim Brotherhood” (ie the Tripoli-based government), Libya’s Madkhalis do not appear to have a preferred allegiance in the rivalry between Tripoli’s Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (PC/GNA) and Haftar’s military coalition (Arabi21.com, September 21, 2016). Indeed, they appear to be covering their bases by supporting both rivals without coming into direct conflict with either.

The Madkhalis in Tripoli are represented by the Rada Special Deterence Force, led by Abd al-Rauf al-Kara. Nominally loyal to the PC/GNA but operating largely independently of government control, they act as a self-appointed police force complete with private jails reputed to be dens of torture (Middleeasteye.net, January 15).

Meanwhile the growing Madkhali armed presence in Benghazi appears to be meeting resistance. The January 25 twin car-bombing that killed 41 people in Benghazi, including LNA commander Ahmad al-Fitouri, appears to have targeted the Baya’at al-Radwan mosque frequented by Madkhalist militia members (Libya Herald, January 23). The Madkhalists also dominate the 604th Infantry Battalion in Misrata (Libya Tribune, November 4, 2017).

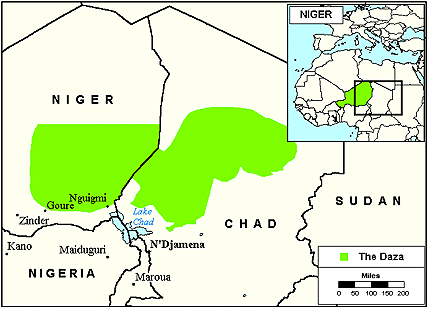

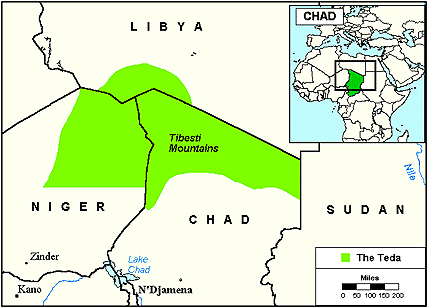

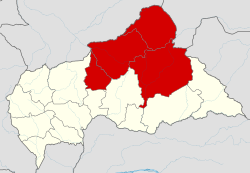

Body-Snatching at Kufra Oasis

A combination of fresh water and nearly impassable desert depressions on three sides makes southeast Libya’s remote Kufra Oasis an inevitable stop for cross desert convoys or caravans. Some 1,500 km from the Libyan coast, Kufra is now a major stop for the flow of illegal migrants that Kufra mayor Muftah Khalil says is overwhelming local security services (Libya Observer, March 5). Since the 2011 Libyan Revolution, Kufra has several times erupted in tribal violence, usually pitting the Zuwaya Arabs against indigenous black semi-nomadic Tubu tribesmen, whose homeland stretches across southern Libya, northern Chad, northwestern Sudan and northeastern Niger. There is long-standing friction between the two communities – the Zuwaya were only able to take possession of Kufra in 1840 by driving out the Tubu.

Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi

Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi

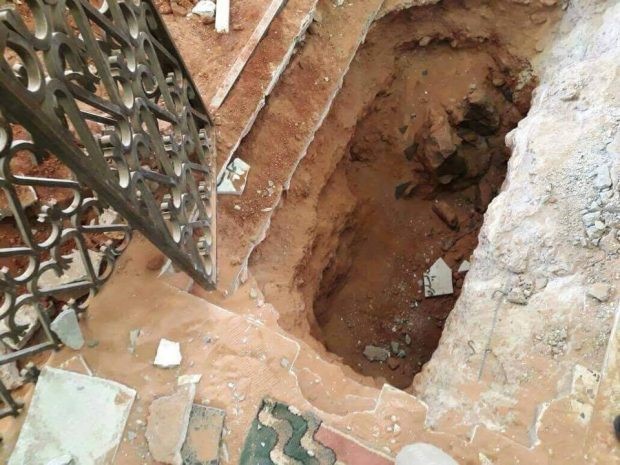

Things have been heating up in the Kufra region in recent months, as Sudanese mercenaries clash with LNA forces and Subul al-Salam, a local Madkahlist militia affiliated with the LNA. In the last days of 2017, Subul al-Salam attacked al-Taj (“The Crown”), a height overlooking the Kufra Oasis, destroying the funerary shrine of Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi, who built a proto-Islamic state in the Sahara and Sahel from 1859 until his death in 1902, and stealing his body.

The emptied tomb of Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi (Libya Observer)

The emptied tomb of Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi (Libya Observer)

A former representative for Kufra, al-Tawati al-Ayda, insisted that the vehicles used in the attack bore the insignia of the LNA. He also suggested the attack was inspired by the arrival in Kufra of Tripoli Madkhalist preacher Majdi Hafala (Libya Observer, January 2).

The Sanusi are a conservative Sufi religious order that grew into a powerful political and military organization in the 19th and early 20th centuries, resisting invasion by the French and later the Italians. Founded in Mecca by Muhammad al-Mahdi’s Algerian father in 1837, the order’s rapid growth after moving to Libya in 1843 attracted the attention of the Ottoman rulers of Libya and the movement moved south, out of Ottoman control, to the oasis of Jaghbub in 1856.

The conservative asceticism at the core of the movement had wide appeal in the desert communities and tribes. This was especially true in the southern oasis of Kufra, to which al-Mahdi moved the Sanusi headquarters in 1895. Using the trade routes that ran through Kufra, al-Mahdi introduced the commerce-friendly Sanusi brand of Islam to the Saharan and sub-Saharan interior of Africa. The Zuwaya Arabs of Kufra became adherents to the Sanusi tariqa, or path, and defenders of the Sanusi family. Today, the Zuwaya form the core of the Subul al-Salam militia responsible for the assault on al-Taj.

While they enjoyed more influence in Cyrenaïca than Tripolitania, the Sanusis eventually formed Libya’s post-Second World War pro-Western monarchy between 1951 and 1969. There is some support in Cyrenaïca for the restoration of the exiled royals as a means of bringing rival government factions together. The current heir to the Libyan throne is Muhammad al-Sanusi, who has not pursued a claim to a revived Sanusi constitutional monarchy, but equally has done nothing to discourage discussions about it within Libya.

After overthrowing the Sanusi monarchy in 1969, Qaddafi began a campaign to malign the Sanusis as the embodiment of the inequities of the old regime and a challenge to the peculiar blend of socialism and Islam he propagated in his Green Book. Attitudes shaped by Qaddafist propaganda against the Sanusis still color the way the order is regarded by many modern Libyans.

The desecration at al-Taj was quickly denounced by the Presidency Council in Tripoli. The Dar al-Ifta (Fatwa House) run by Grand Mufti Sadiq al-Ghariani blamed the imported Madkhalilst trend: “Madkhalists are being sent to Libya by Saudi Arabia in order to destabilize the country and abort the revolution. These are all loyalists of Khalifa Haftar and his self-styled army in eastern Libya” (Libyan Express, January 2). Dar al-Ifta also used the incident to launch a broader attack on Libya’s Madkhalists, which it accused of detaining, torturing and murdering Islamic scholars and clerics who failed to fall into line with the Salafists sect (Libya Observer, January 2). The Madkhalis in turn accuse al-Ghariani of association with the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood, and hence a follower of the late revolutionary Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood leader Sayyid Qutb (executed in Egypt in 1966), the Madkhalis’ ideological arch-enemy.

Surprisingly, this is not the first time al-Mahdi’s corpse has gone missing – it was disinterred by unknown individuals in 2012 and reburied in a nearby cemetery, before relatives recovered it and returned it to the shrine at al-Taj (Libya Observer, December 30, 2017).

Operation Desert Rage

Chadian and Sudanese rebels driven from their homelands have turned mercenary in Libya to secure funding and build their arsenals. [2] Grand Mufti al-Ghariani has accused Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) of funding the recruitment of African mercenaries to occupy southern Libya on behalf of Haftar’s LNA (Libya Observer, March 13). In practice, the rebels have found employment from both the LNA and the PC/GNA government in Tripoli.

Sudanese fighters of Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) killed six members of the LNA’s 106 and 501 Brigades engaged in border security near Jaghbub Oasis on January 15. A seventh LNA soldier was abducted. The area was the site of an earlier clash in October 2016 between JEM and Kufra’s Subul al-Salam militia in which 13 JEM fighters were killed (Libya Herald, October 20, 2016).

Sudanese Forces at Jabal ‘Uwaynat (Libya Observer)

Sudanese Forces at Jabal ‘Uwaynat (Libya Observer)

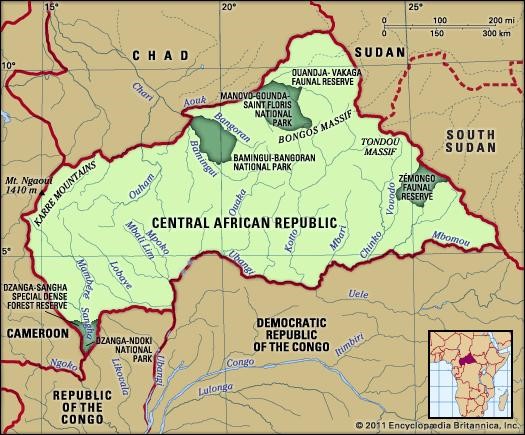

The LNA responded to the death of the border guards with “Operation Desert Rage,” which opened with January 20 airstrikes against what the LNA alleged were Sudanese and Chadian rebels near Rabyana Oasis, 150 km west of Kufra. Possibly involving Egyptian aircraft, the strikes caused “heavy losses” to a 15-vehicle convoy of “terrorists” (TchadConvergence, January 22). The Sudanese and Chadians had been prospecting for gold in the newly discovered deposits near Jabal ‘Uwaynat, the remote meeting point of Egypt, Libya and Sudan (Egypt Today, January 23). The commander of the LNA’s Kufra military zone, al-Mabruk al-Ghazwi, said patrols had been sent in every direction to prevent JEM fighters from escaping (Libya Observer, January 20).

Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) spokesman Brigadier Ahmad al-Shami confirmed the presence of Darfuri rebels working as mercenaries in Libya last summer, noting their greatest concentrations were at the oases of Kufra and Rabyana as well as the city of Zintan in Libya’s northwest (Libya Observer, July 20, 2017).

The ‘Invasion’ of Sabha

The Tubu, Awlad Sulayman Arabs and African mercenaries are also engaged in a new round of post-revolutionary fighting in Sabha, capital of Libya’s southwestern Fezzan region.

Following the 2011 revolution, the Awlad Sulayman took advantage of shifts in the local tribal power structure to take over Sabha’s security services and regional trafficking activities. This brought the Arab group into conflict with the Tubu and Tuareg, who traditionally controlled the cross-border smuggling routes. The result was open warfare in Sabha in 2012 and 2014. One of the leading Awlad Sulayman commanders at the time was Ahmad al-Utaybi, now commander of the Awlad Sulayman-dominated 6th Infantry Brigade.

In mid-February, Haftar announced his decision to join the 6th Brigade with the LNA, but al-Utaybi quickly declared his Brigade’s loyalty was to the defense ministry of the GNA government in Tripoli. Following al-Utaybi’s refusal to commit his forces to the LNA, Haftar announced his replacement as commander of the 6th Infantry Brigade with Brigadier Khalifa Abdul Hafiz Khalifa on February 25, though Khalifa has been unable to assume command (Al-Sharq al-Aswat, February 27). At the same time, the 6th Brigade came under heavy attack from alleged Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries working for Haftar. According to al-Utaybi: “The militias who attacked our locations wanted to take control of it and then seize the entire southern region because the fall of the Brigade means the fall of the security of the south” (Libya Observer, February 24).

Al-Utaybi claims that the fighting is not tribal-based, but is rather a clash between the 6th Brigade and groups loyal to Haftar, consisting largely of Tubu mercenaries from Chad, Niger and Sudan (Libyan Express, March 1; Libya Observer, March 2). [3] There are also claims that the conflict has much to do with the collapse of the Italian agreement with the southern tribes providing them with funding and development in return for suppression of migrant flows through Libya to Europe (Eyesonlibya.com, February 27).

Damage to Sabha Castle from shelling (Libya Observer)

Damage to Sabha Castle from shelling (Libya Observer)

The 6th Brigade was forced to withdraw into Sabha’s Italian colonial-era fortress. The historic building has been heavily damaged in this round of fighting, with the Libyan Antiquities Authority protesting that: “Those who do not wish us well are seeking to obliterate Libyan history and civilization” (Libya Observer, March 5). The fighting consists largely of artillery attacks on the fortress and ethnic neighborhoods, as well as sniping, assassinations and drive-by killings.

Sabha’s mayor, Hamid al-Khayali, insists that well-armed Chadian and Sudanese mercenaries flying the flags of “African countries” were taking advantage of the region’s insecurity: “This is an occupation of Libyan land. This is on the shoulders of all Libyans. The south is half-occupied and some Sabha areas are occupied by foreign forces from Sudan, Chad and other countries; why is the Libyan army silent about this?” (Libya Observer, February 25; Libyan Express, February 27).

The long-standing Arab suspicion of the Tubu was reflected in a Presidency Council statement in late February praising the 6th Brigade’s defense of Sabha against “mercenaries” intent on changing the south’s demographic structure from Arab-dominant to Tubu-dominant (Libya Observer, February 27).

Roadblock to Political Resolution

The abduction of Muhammad al-Mahdi’s body was, like earlier Salafist demolitions of Sufi shrines in coastal Libya, both a demonstration of Madkhali determination to reform Libya’s religious landscape and a provocation designed to reveal what real resistance, if any, exists to prevent further Madkhalist encroachments on Libyan society.

For now the Madkhalists are in ascendance and have made important, even unique, inroads in assuming control of various security services across the country, regardless of which political factions are locally dominant. Reliable salaries, superior weapons and a degree of legal immunity ensure a steady supply of recruits to the Madkhali militias.

However, the Madkhali rejection of democracy, and their indulgence in extra-judicial law enforcement and theological disputes with nearly every other form of Islamic observance, ensures their growing strength will inhibit any attempt to arrive at a democracy-based political solution in Libya.

Notes

[1] “UNSMIL statement on the ongoing violence in Sabha,” March 13, 2018, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/unsmil-statement-ongoing-violence-sabha

[2] The Chadian groups include the Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT), the Conseil du commandement militaire pour le salut de la République (CCMSR) and the Rassemblement des forces pour le changement (RFC). The Sudanese groups are all from Darfur, and include the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), the Sudan Liberation Movement – Unity (SLM-Unity) and the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army – Minni Minnawi (SLM/A-MM). The latter two attempted to return to Darfur in 2017 but were badly defeated by units of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

[3] Libyan Arabs commonly describe the Libyan Tubu as “foreigners” and “illegal immigrants” despite their historic presence in the region.

This article first appeared in the April 6, 2018 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.