Andrew McGregor

November 30, 2010

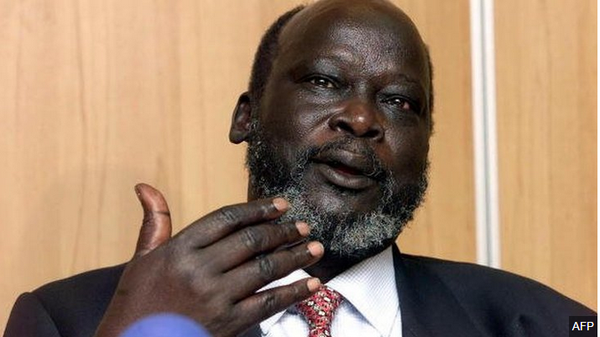

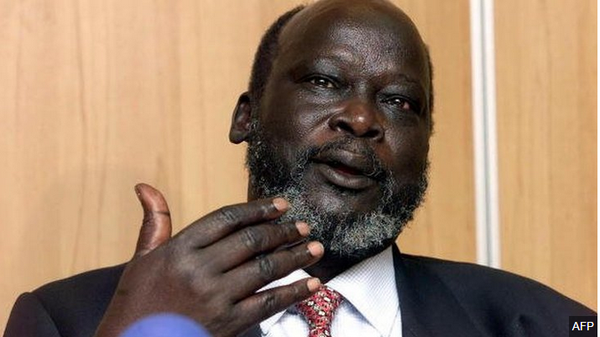

With the January 9, 2011 Referendum on South Sudanese independence only weeks away, a long-time rebel commander turned politician stands to become the first president of a new African nation, a nation with abundant oil reserves but a highly uncertain future. Salva Kiir Mayardit, a Roman Catholic Rek Dinka from Warrap state in Bahr al-Ghazal province, fought in both of Sudan’s civil wars, finishing the second as chief military commander of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M). [1]

Salva Kiir Mayardit

Background

In 1967, a 17-year-old Salva Kiir joined the Ayanya Rebellion (1955-1972), an armed effort to establish a separate state in South Sudan. Following the 1972 Addis Ababa Agreement that brought an end to Sudan’s First Civil War, Kiir was among those Anyanya guerillas who were integrated into the Sudanese Armed Forces or the Wildlife Protection Service (many other irreconcilable fighters went south to Idi Amin’s Uganda). He graduated from the Sudan Military College in Omdurman and went on to serve as a major in Sudanese military intelligence.

Having joined the renewed Southern insurgency in 1983, Salva Kiir’s skills and influence were recognized when he was made a member of the SPLA/M High Command Council, alongside notable Southern soldiers such as Colonel John Garang de Mabior (who emerged as SPLA/M Chairman), Lieutenant Colonel Karabino Kuanyin Bol, Major Arok Thon Arok and Lieutenant Colonel William Nyuon Bany. Of these figures, only Salva Kiir survives.

Kiir began to play an important political/diplomatic role in 1993 when he led the SPLM delegation to the OAU-sponsored Sudan Peace Talks in Abuja. Kiir took over as John Garang’s deputy following the death of William Nyoun Bany in 1996. He again led the SPLM delegation to the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) sponsored Sudan peace talks in Kenya that paved the way for the ground-breaking 2004 Machakos Protocol.

Increasing differences between Kiir and SPLA chairman John Garang in 2004 led to unsuccessful attempts by Garang to replace the popular military leader as commander-in-chief of the SPLA (Sudan Vision, July 8, 2005). There were in turn rumors that Kiir was planning to depose Garang and install veteran politician Bono Malwal in his place.

John Garang was Sudan’s foremost advocate of a united but democratic and federal Sudan that would incorporate Sudan’s many peoples into Sudan’s narrowly defined power structure, traditionally dominated by three Arab tribes of North Sudan. His vision on a “New Sudan” often placed him at odds with the rest of the SPLA/M leadership, many of whom advocated for an independent South Sudan. These divisions grew as the civil war showed few signs of ending and attitudes towards the North hardened. Garang became increasingly intolerant of internal challenges to his program and used force to maintain ideological discipline. However, Garang’s vision appears to have died with him in the helicopter crash that claimed his life in July 2005, only months after negotiating the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) that ended the civil war. Unlike Garang, Salva Kiir is a separatist who quickly changed the official direction of the SPLM into an independence movement from a national unity movement, finding much support and little opposition for the change.

The CPA established a Government of National Unity (GNU) in Khartoum and a Government of South Sudan (GoSS) based in Juba, with the GoSS President automatically becoming first vice-president of Sudan. Since Garang’s death, Kiir has served as first vice-president of the Sudanese GNU and president of the GoSS. Kiir was not everyone’s choice as the movement’s new leader, but it was important to follow the established line of succession for the SPLA/M to maintain its international credibility as a partner in the CPA and prevent the movement from shattering. The result was a unanimous vote on the part of the SPLA/M High Command Council to elect Kiir as SPLM chairman and commander-in-chief of the SPLA. He was reelected by unanimous vote in 2008.

Kiir is not a forceful speaker but has used other methods to establish his public presence. Like most Nilotic peoples of the South Sudan, Kiir is unusually tall by Western standards and cuts a distinctive and memorable figure in his typical black suit, red tie and broad-brimmed black hat (the latter innovation has since been adopted by many of Darfur’s rebel leaders).

Disengaging from the New Sudan

It was widely expected that John Garang’s appointment to first vice-president of the Sudan under the terms of the CPA would mark the beginning of a new approach to the crisis in Darfur, but his death and the subsequent takeover of Salva Kiir as vice-president instead marked the beginning of a more muted approach by the SPLA/M to the Darfur issue. The movement’s attempts to unite the fractious Darfur rebels have been largely unsuccessful and even the SPLA/M’s limited efforts to help forge a solution to the Darfur crisis have been discouraged by Khartoum. Sudan’s National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) recently demanded that South Sudan arrest Darfur rebel leaders who are resident in the South (Sudan Tribune, November 8). Salva Kiir has nonetheless encouraged the unification of the many Darfur rebel movements and his discussions with Dr. Khalil Ibrahim’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM – the strongest rebel group in Darfur) have proved especially worrisome for Khartoum.

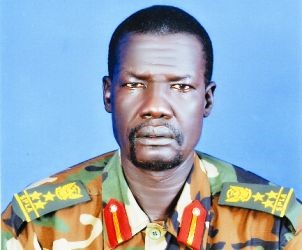

Late SPLA/M Chairman John Garang Mabior

Late SPLA/M Chairman John Garang Mabior

With Kiir uninterested in the national presidency, the SPLM decided to run Yasir Sa’id Arman, a northerner and longtime member of the SPLM leadership, for the presidency in the April elections. However, Arman and the other leading challenger, former president and Umma Party leader Sadiq al-Mahdi, both decided to withdraw from the election citing irregularities. Following the withdrawal of the SPLM from the presidential contest, Kiir surprised many by saying he had voted to re-elect National Congress Party (NCP) chairman Omar al-Bashir as president of Sudan (Sudan Tribune, April 18).

Kiir has accused Khartoum of sending only 26% of Sudan’s oil revenues to the southern capital of Juba, rather than the 50% called for in the CPA (Sudan Tribune, October 1). Nearly 50% of the revenues that have reached Juba have gone to an ambitious rearmament program in the South intended to place the SPLA on a more even footing with the conventional forces of the SAF. Efforts have even begun to create a Southern Air Force.

Pardoning Thy Enemies

Under the terms of the CPA, the SAF and the SPLA became the only legal armed groups in Sudan. The many independent or pro-Khartoum militias operating in the South were given the option of disarming or joining one or the other legal armed forces. Naturally it became imperative for the SPLA/M to integrate these forces rather than allow pro-Khartoum armed groups to continue their existence in the South, but the process has been slow and even appeared to be failing in the last year as a number of SPLA commanders rebelled against Salva Kiir’s government in the aftermath of the April elections, which the dissidents complained were fixed in favor of Kiir loyalists.

In January 2006, Kiir’s negotiations with longtime anti-SPLA militia commander Paulino Matip Nhial resulted in the traditionally pro-Khartoum Bul Nuer commander joining the SPLA/M. The so-called “Juba Declaration” incorporating “other armed groups” into the SPLA/M was a major coup for Kiir and an important step in convincing remaining Nuer and other tribal dissidents to cooperate with the SPLA/M in the lead-up to the referendum. Paulino Matip was rewarded by being made Deputy Commander of the SPLA, with promotion to full General in May, 2009 (splamilitary.net, May 31, 2009).

As Kiir began preparing the South Sudan for the independence referendum (and the possible outbreak of hostilities following a vote for separation), a series of small rebellions and mutinies by SPLA/M generals and officers threatened to destroy any chance of a unified approach to the question of separation. Many saw the hand of Khartoum and its proven “divide and conquer” approach to any threat to central authority behind these rebellions. Though Kiir initially responded with force to these challenges, he ultimately turned to an amnesty in September 2010, which, combined with the seeming inevitability of a Southern vote for independence, succeeded in bringing nearly all the rebel commanders back into the fold. It was a bold gambit – before the decision many Southerners were calling for the utter destruction of the rebel commanders; after the decision, the families of loyal SPLA troops killed in combating the rebellions were outraged at the pardons (New Sudan Vision, October 11). The main individuals concerned in the amnesty were the following:

- Lieutenant General George Athor: George Athor, a Dinka tribesman, ran as an independent for governor of Jonglei State in the April elections after having failed to receive the nomination of the SPLM. Unhappy with his loss in the polls, Athor and his men began a series of heavy clashes with SPLA forces in late April through May. Athor threatened to take the Unity (Wilayah) State capital of Malakal while SPLM Secretary General Pagan Amun accused him of being a pawn of the NCP (Sudan Tribune, May 17; al-Hayat, May 14). Athor’s men are now reported to be rejoining SPLA forces in Jonglei under the command of Major General Peter Bol Kong (Sudan Tribune, November 9).

- Major General Gabriel Tang: Tang led a pro-government militia in the civil war. After clashing with the SPLA in 2006, Tang withdrew to Khartoum, where his forces were integrated with the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF). An unannounced return to Malakal in February 2009 led to further clashes with the SPLA that left hundreds dead before Tang returned to Khartoum.Tang responded to the amnesty offer within days by flying to Juba and declaring his allegiance to the SPLA/M (Sudan Tribune, October 15).

- David Yau Yau: A civilian from Jonglei, David Yau Yau is a member of the Murle Tribe and is tied to George Athor. Yau launched a small rebellion in Jonglei’s Pibor county after being defeated in the April elections. He was not named in the September 29 pardons, but is expected to follow George Athor’s lead (Miraya FM [Juba], July 5; Small Arms Survey, November 2010).

- Colonel Gatluak Gai: A Colonel in the Prisons Service of South Sudan, this relatively unknown officer from the Jaglei Nuer led a short-lived rebellion in May-June against the SPLA/M in Unity State following the April elections. Several sources reported Missiriya Arab fighters amongst Gai’s force. The Colonel fled north after clashes with the SPLA and has not responded to offers of an amnesty (Gurtong.net, November 18; Sudan Tribune, June 4; Jonglei.com, June 30; Small Arms Survey, November 2010).

Preparing for the Referendum

Kiir’s decision not to contest the April 2010 Sudanese presidential elections in favor of running for president of the South Sudan was a clear sign the SPLA/M was no longer a national movement. With little real opposition, Kiir was returned to office with 93% of the vote. As president of the South Sudan, Kiir was automatically made vice-president of the national Sudanese government. In the ever-revolving world of Sudanese politics, Dr. Riek Machar, a Nuer warlord who spent many years dedicated to the destruction of the SPLA/M, was made vice-president of the GoSS.

Salva Kiir’s statement to supporters in Juba that he intended to vote for separation because the North had failed to make unity attractive was condemned by NCP official Rabie Abd al-Lati Obeid, who noted that the CPA “stated clearly that the SPLM with the National Congress Party should work together to achieve unity and to make unity attractive during the interim period…This is a clear violation of the CPA and it is against that agreement…” (Sudan Tribune, October 1; VOA, October 3).

After his return from recent meetings with UN and American officials, Kiir told a crowd in Juba:

Critically important is that the referenda take place on time, as stipulated in the CPA. Delay or denial of the right of self-determination for the people of Southern Sudan and Abyei risks dangerous instability. There is without question a real risk of a return to violence on a massive scale if the referenda do not go ahead as scheduled… We are genuinely willing to negotiate with our brothers in the North, and are prepared to work in a spirit of partnership to create sustainable relations between Northern and Southern Sudan for the long-term. It is in our interest to see that the North remains a viable state, just as it should be in the interests of the North to see Southern Sudan emerge a viable one too. The North is our neighbor, it shares our history, and it hosts our brothers and sisters. Moreover, I have reiterated several times in my speeches in the past that even if Southern Sudan separates from the North it will not shift to the Indian Ocean or to the Atlantic Coast! (Gurtong.net, October 4).

The most contentious issue Kiir must deal with is the future of Abyei, a disputed territory lying along the border of Kordofan (North) and Bahr al-Ghazal (South). A separate referendum to be held simultaneously with the independence vote will determine whether Abyei joins the North or the South. Most of the district’s Ngok Dinka are expected to vote for unification with the South, but the nomadic Missiriya Arabs of South Kordofan who pasture their herds there demand to be included in the voting. So far this issue has not been resolved and there are few signs the referendum will take place on time. Khartoum has said a postponement is necessary and Missiriya anger is threatening to create new violence in the already war-ravaged territory. Kiir has promised an SPLM government can provide services to the Missiriya, but cannot hand over the land to Missiriya control (Miriya FM [Juba], November 17). SPLM officials now speak of annexing Abyei if a referendum cannot be held, but only after making significant financial concessions to Khartoum.

Kiir has promised the Missiriya will continue to be allowed to graze their animals in an independent South Sudan: “Even if they come up to Juba, nobody will stop them” (Sudan Tribune, October 1). However, Kiir may find it difficult to back up such a promise under new attitudes to the presence of Arab nomads in an independent South Sudan. Many Southerners have fresh memories of the Missiriya’s role in the pro-Khartoum murahileen militias, accused by many Southerners of conducting widespread atrocities against the civilian population designed to break support for the SPLA/M during the civil war.

Conclusion

Though Kiir has managed to build a façade of unity going into the independence referendum, he has also surrounded himself with former rivals of questionable loyalty. Tribal tensions between Nuer and Dinka are never far from the surface and there is every possibility an aggravated dispute over posts, appointments and revenue sharing in an independent South could easily lead to a localized civil war, fueled by opportunists in Khartoum who would like to see the new state fail. As the vote grows ever closer there are indications that the leaders of the NCP, highly skilled at manipulating the international community, may attempt to force a postponement of the referendum on technical grounds. Kiir has said that the SPLA/M will not declare unilateral independence, but will instead press forward with the vote without the cooperation of Khartoum. The legality of such a step, not provided for in the 2005 CPA, would give Kiir’s opponents ample ammunition to disrupt the independence movement.

Note

- The SPLA/M’s structure of a dual military/political command has served as a model for a number of other Sudanese rebel movements since its formation in 1983.

This article first appeared in the November 30, 2010 issue of the Militant Leadership Monitor